Big Tech, also known as the Tech Giants, Big Four or Big Five, is a name given to the four or five largest, most dominant companies in the information technology industry of the United States. The Big Four presently consists of Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, and Meta (Facebook)—with Microsoft completing the Big Five. Broader groupings of Big Tech may also include Twitter, Netflix, and Tesla. Companies like Tencent and Alibaba Group serve as the equivalents of Big Tech in Asian regions.

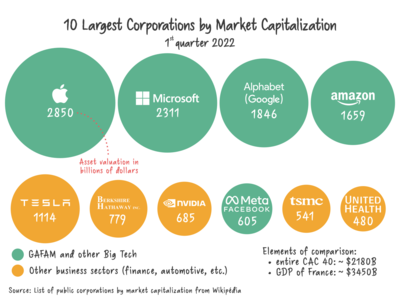

The tech giants are the dominant players in their respective areas of technology, namely: e-commerce, online advertising, consumer electronics, cloud computing, computer software, media streaming, artificial intelligence, smart home, self-driving cars, and social networking. They have been among the most valuable public companies globally, each having had a maximum market capitalization ranging from around $1 trillion to above $3 trillion. They are additionally considered to be among the most prestigious and selective employers in the world, especially Google.

Big Tech companies typically offer services to millions of users, and thus can hold sway on user behavior as well as control of user data. Concerns over monopolistic practices have led to antitrust investigations from the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission in the United States, and the European Commission. Commentators have questioned the impact of these companies on privacy, market power, free speech, censorship, national security and law enforcement. It has been speculated that it may not be possible to live in the digital world day-to-day outside of the ecosystem created by the companies.

The concept of Big Tech is analogous to the consolidation of market dominance by a few companies in other market sectors such as "Big Oil" and "Big Media". "Big Tech" may also refer to historical versions of this concept, with the likes of Microsoft, IBM and AT&T considered to be dominant companies in this industry in the mid to late 20th century.

Origin

The idea of "big" technology companies had entered the public consciousness around 2013, as some economists saw signs of these companies gaining appreciable dominance without any regulation, and were no longer considered disruptive start-up companies following the early 2000s dot-com bubble. The term became popularized and labeled as "Big Tech" around 2017 in the wake of the investigation into possible Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections, as the roles that these technology companies has played with access to wide amounts of user data or big data and ability to influence their users came under Congressional review. The use of "Big Tech" was similar to how the largest oil companies were grouped under Big Oil following the 1970s energy crisis, or how the major cigarette producers were grouped as Big Tobacco as Congress began seeking regulation on that industry, or how, at the turn of the 21st century, the global commercial media system came to be dominated by a small number (around nine or ten) of extremely powerful and mainly U.S.-based transnational media corporations called collectively the "Big Media" or global "Media Giants".

Membership and definitions

The term Big Tech is often broken down into more specific sub-groupings, often referred to by the following names or acronyms. Alphabet Inc., the parent company of Google, may be represented as a "G" in these acronyms, while Meta Platforms, the rebranding of Facebook, Inc., may be represented by "F".

Big Four

Google (Alphabet), Amazon, Facebook (Meta), and Apple are commonly referred to as Big Four or GAMA. They have also been referred to as "The Four", "Gang of Four", and as the "Four Horsemen". The GAMA were known as GAFA before Facebook rebranded its name to Meta in 2021.

Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, author Phil Simon, and NYU professor Scott Galloway have each grouped these four companies together, on the basis that those companies have driven major societal change via their dominance and role in online activities. This is unlike other large tech companies such as Microsoft and IBM, according to Simon and Galloway. In 2011, Eric Schmidt excluded Microsoft from the grouping, saying "Microsoft is not driving the consumer revolution in the minds of the consumers."

Big Five

A more inclusive grouping, referred to as Big Five or GAMAM defines Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple, and Microsoft as the tech giants.

Besides Saudi Aramco, the GAMAM companies were the five most valuable public corporations in the world in January 2020 as measured by market capitalization. The GAMAM were known as GAFAM before Facebook rebranded its name to Meta in 2021.

FANG, FAANG, and MAMAA

FANG was an acronym coined by Jim Cramer, the television host of CNBC's Mad Money, in 2013 to refer to Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google. Cramer called these companies "totally dominant in their markets". Cramer considered that the four companies were poised "to really take a bite out of" the bear market, giving double meaning to the acronym, according to Cramer's colleague at RealMoney.com, Bob Lang.

Cramer expanded FANG to FAANG in 2017, adding Apple to the other four companies due to its revenues placing it as a potential Fortune 50 company. Following Facebook, Inc.'s name change to Meta Platforms Inc. in October 2021, Cramer suggested replacing FAANG with MAMAA; this included replacing Netflix with Microsoft among the five companies represented as Netflix's valuation had not kept up with the other companies included in his acronym; with Microsoft, these new five companies each had market caps of at least $900 billion compared to Netflix's $310 billion at the time of Meta's rebranding.

In November 2021, The Motley Fool parodied MAMAA and FAANG by coming up with the acronym MANAMANA, which includes Microsoft, Apple, Netflix, Alphabet, Meta, Amazon, Nvidia, and Adobe.

Other companies

Although smaller in market capitalization, Netflix, Twitter, Snap, and Uber are sometimes referred to as "Big Tech" due to their popular influence. Twitter being categorized as Big Tech has featured in political debates and economic commentary due to perceived political and social influence of the platform.

There were also two Chinese technology companies in the top ten most valuable publicly traded companies globally at the end of the 2010s – Alibaba and Tencent. Smyrnaios argued in 2016 that the Asian giant corporations Samsung, Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent could or should be included in the definition. Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Xiaomi, collectively referred to as BATX, are often seen as the competitor companies of Big Tech in China's technology sector. ByteDance has also been considered Big Tech. Together, the combination of the Big Five, IBM, Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent has been referred to as "G-MAFIA + BAT".

Tesla

Automaker Tesla has frequently been deemed one of the Big Tech companies, though its inclusion is subject to wide debate. Opponents to its designation as a tech company include Stephen Wilmot, a correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, who raises concerns regarding the supply chain, especially raw materials, semiconductor shortages, and the price of electric vehicle batteries. Business Insider concurs, stating that because Tesla makes more cars, it should be classified as an automaker and should aspire to be more like Honda. In support of the designation include Al Root of Barron's, who argues while Tesla isn't a good tech company due to factors of the car market, but regardless still a tech company. Fortune also designated Tesla as a tech company when reporting Big Tech's 2022 Q1 earnings, and The Washington Post argues that Tesla's vehicles are comparable to Apple's iPhone and its walled garden ecosystem.

Market dominance

The tech giants have replaced the energy giants such as ExxonMobil, BP, Gazprom, PetroChina, Chevron, and Shell ("Big Oil") from the first decade of the 21st century at the top of the NASDAQ stock index. They have also outpaced the traditional big media companies such as Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, and Comcast by a factor of 10. In 2017, the five biggest American IT companies had a combined valuation of over $3.3 trillion, and made up more than 40 percent of the value of the Nasdaq 100. It has been observed that the companies remain popular by providing some of their services to consumers for free.

Alphabet (Google)

Google is the leader in online search (Google Search), online video sharing (YouTube), email services (Gmail), web browsing (Google Chrome) and online mapping-based navigation (Google Maps and Waze), mobile operating systems (Android) and online storage (Google Drive) as well as a variety of other popular tech services. Google Cloud is the third largest player in the cloud computing market after Amazon and Microsoft. Google and Facebook hold a duopoly over the digital advertising market. Google's advertising business makes up 82% of its revenues and most of its profit.

Alphabet has emerged among tech firms as the global leader in AI/ML, autonomous vehicles, and quantum computing. Waymo, Alphabet's self-driving car subsidiary, is considered to be the leader in autonomous vehicle technology and was the first self-driving company to offer a publicly available robo-taxi service in 2021. With its Sycamore processor, Google is seen as the leader in quantum computing and in 2019, it claimed Sycamore had achieved quantum supremacy.

Amazon

By 2017, Amazon was the dominant market leader in e-commerce with 40.4% market share; cloud computing, with nearly 32% market share, and live-streaming with Twitch owning 75.6% market share. With Amazon Alexa and Echo, Amazon is additionally the market leader in the area of artificial intelligence-based personal digital assistants and smart speakers (Amazon Echo) with 69% market share followed by Google (Google Nest) at 25% market share.

Amazon Web Services made up 59% of the Amazon's profit in 2020, and more than half of the company's profit every year since 2014. Following the development of EC2 by Amazon in 2006, Google and Microsoft followed in 2008 with Google App Engine (expanded to Google Cloud Platform since 2011) and Windows Azure (Microsoft Azure since 2010).

Apple

Apple sells high-margin smartphones and other consumer electronics devices, sharing a duopoly with Google in the field of mobile operating systems: 27% of the market share belonging to Apple (iOS) and 72% to Google (Android).

Meta (Facebook)

Meta Platforms, formerly Facebook, Inc. until its rebranding in October 2021, is the parent company of the Facebook social network, as well as owner of the Instagram online image sharing service and WhatsApp online messaging service.

Facebook had acquired Oculus in 2014, entering the virtual reality market.

Microsoft

Microsoft continues to dominate in desktop operating system market share (Microsoft Windows) and in office productivity software (Microsoft Office). Microsoft is also the second biggest company in the cloud computing industry (Microsoft Azure), after Amazon, and is also one of the biggest players in the video game industry (Xbox). Microsoft is also the dominant player in enterprise software (Microsoft 365, also available for consumers), and business collaboration suite (Microsoft Teams).

Causes

Smyrnaios argued in 2016 that four characteristics were key in the emergence of GAMA: the theory of media and information technology convergence, financialization, economic deregulation and globalization. He argued that the promotion of technology convergence by people such as Nicholas Negroponte made it appear credible and desirable for the Internet to evolve into an oligopoly. Autoregulation and the difficulty of politicians to understand software issues made governmental intervention against monopolies ineffective. Financial deregulation led to GAFA's big profit margins (all four except for Amazon had about 20–25 percent profit margins in 2014 according to Smyrnaios).

Innovation

A major contributing factor towards the growth of Big Tech is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, passed into law in 1996. Section 230 removed the liability for online services from hosting user-generated content that is deemed illegal, providing them safe harbor as long as they acted on such material when discovered in good faith. This allowed service providers in the early days of the Internet to expand offerings without having to invest heavily into content moderation. For this reason, Section 230 is often called "The twenty-six words that created the Internet", as it helped to fuel innovation in online services over the years that allowed Big Tech companies to grow and flourish.

"For decades, whole regions, nations even, have tried to model themselves on a particular ideal of innovation, the lifeblood of the modern economy. From Apple to Facebook, Silicon Valley’s freewheeling ecosystem of new, nimble corporations created massive wealth and retilted the world’s economic axis." The tech giants began as small engineering-focused firms building new products when their larger competitors were less innovative (such as Xerox when Apple was founded in 1976). The companies engaged in timely investment in rising technologies of the personal computer era, dotcom era, e-commerce, rise of mobile devices, social media, and cloud computing. The characteristics of these technologies allowed the companies to expand quickly with market adoption. According to Alexis Madrigal, the style of innovation that initially drove Silicon Valley firms to grow is being lost, shifting to a form of growing through acquisitions. Additionally, large companies tend to focus on process improvements rather than new products. However, the Big Tech firms all rank near the top on the list of companies by research and development spending.

"Cloud wars" between the tech giants have been observed as a major factor over the years, as the companies have competed on developing more efficient cloud computing services.

Among those who believe that acquisitions will weaken an original innovative atmosphere is scholar Tim Wu, Wu pointed out that when Meta acquired Instagram, it simply eliminated a competitive threat that may have presented a fresher competitor had it remained independent. He also states however that when Microsoft first emerged, with its innovations in personal computing and operating systems, it created platforms for new innovations by others. Wu formulated the idea of oligopoly "kill zones" created by acquiring competitors that approach their market. Big Tech operating in digital markets and being inherently focused on technology mean that Big Tech is more likely to focus on innovation than other groups of large industry dominating corporations before them. According to a report by the think tank ITIF, acquisitions being possible supports innovation, arguing the larger firm is less likely to simply copy the process of the smaller firm.

Globalization

According to Smyrnaios, globalization has allowed GAMAM to minimize its global taxation load and pay international workers much lower wages than would be required in the United States.

Oligopoly maintenance

Smyrnaios argued in 2016 that GAMA combines six vertical levels of power, data centers, internet connectivity, computer hardware including smartphones, operating systems, Web browsers and other user-level software, and online services. He also discussed horizontal concentration of power, in which diverse services such as email, instant messaging, online searching, downloading and streaming are combined internally within any of the GAMA members. For example, Google and Microsoft pay to have their web search engines appear as first and second in Apple's iPhone.

According to The Economist, "Network and scale effects mean that size begets size, while data can act as a barrier to entry."

Capitalism

The 2020 American docudrama film The Social Dilemma argues that capitalism is the root cause of Big Tech's harmful practices.

Antitrust legislation and investigations

United States

In the United States, antitrust scrutiny and investigations of members of Big Tech began in the late 1990s and early 2000s, leading to the first major American antitrust law case against a member of Big Tech in 2001 when the U.S. government accused Microsoft of illegally maintaining its monopoly position in the personal computer (PC) market primarily through the legal and technical restrictions it put on the abilities of PC manufacturers (OEMs) and users to uninstall Internet Explorer and use other programs such as Netscape and Java. At trial, the district court ruled that Microsoft's actions constituted unlawful monopolization under Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit affirmed most of the district court's judgments. The DOJ later announced on September 6, 2001, that it was no longer seeking to break up Microsoft and would instead seek a lesser antitrust penalty in exchange for a settlement by Microsoft in which Microsoft agreed to share its application programming interfaces with third-party companies and appoint a panel of three people who would have full access to Microsoft's systems, records, and source code for five years in order to ensure compliance. On November 1, 2002, Judge Kollar-Kotelly released a judgment accepting most of the proposed DOJ settlement and on June 30, 2004, the U.S. appeals court unanimously approved the settlement with the Justice Department.

In the late 2010s and early 2020s the Big Tech industry again became the center of antitrust attention from the United States Department of Justice and the United States Federal Trade Commission that included requests to provide information about prior acquisitions and potentially anticompetitive practices. Some Democratic candidates running for president proposed plans to break up Big Tech companies and regulate them as utilities. "The role of technology in the economy and in our lives grows more important every day," said FTC Chairman Joseph Simons. "As I’ve noted in the past, it makes sense for us to closely examine technology markets to ensure consumers benefit from free and fair competition."

The United States House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law began investigating Big Tech on an antitrust basis in June 2020, and published a report in January 2021 concluding that Apple, Amazon, Meta, and Google each operating in antitrust manners that requires some type of corrective action that either could be implemented through Congressional action or through legal actions taken by the Department of Justice, including the option of splitting up these companies.

On June 24, 2021 the United States House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law held hearings on earlier introduced bills which would limit the scope of Big Tech. Among those bills was HR 3825, Ending Platform Monopolies Act introduced by Representative Pramila Jayapal which passed through the committee. The specific purpose of the bill is to prohibit platform holders to also compete in those same platforms. For example, Amazon attempted to purchase Diapers.com and when they resisted and refused to sell, Amazon started selling diaper related products at a loss which Diapers.com could not sustain. Amazon being the platform owner as well a player in the platform could easily sustain continued loss. The point came when Diapers.com could not sustain and they eventually, without any other choice ended up selling to Amazon out of fear even though Walmart was willing to pay more.

The issue of consumer welfare arose in the subcommittee but was voted down and rejected as the majority held the opinion that the reason we have these monopolies today is mainly because of the consumer welfare standard. This doctrine was introduced over 100 years ago and the committee would not adopt the consumer welfare standard in HR 3825.

The consumer welfare doctrine is an ideology which states that if the consumer enjoys lower pricing as a result of corporate mergers or decision making then those actions are not generally antitrust, no matter if there has been any damage done to the market or society. The newly appointed chair to the FTC, Lina Khan has held different views as outlined in her publication Amazon's Antitrust Paradox.

The recently introduced bills show that we will eventually drop or diminish the consumer welfare standard and move towards a marketplace welfare standard which promotes competition and levels the playing field for startups and businesses which have not fully grown.

There has been opposition from Big Tech regarding these bills and any legislation to trim them. Mark Zuckerberg of Meta implied that his company's success is important to the national security of the United States. Tim Cook, CEO of Apple spoke to House Speaker, Nancy Pelosi in an attempt to slow down the bills.

The spirit of the antitrust law is to protect consumers from the anticompetitive behavior of businesses that have either monopoly power in their market or companies that have banded together to exert cartel market behavior. Monopoly or cartel collusion creates market disadvantages for consumers. However, the antitrust law clearly distinguishes between purposeful monopolies and businesses that found themselves in a monopoly position purely as the result of business success. The purpose of the antitrust law is to stop businesses from deliberately creating monopoly power.

Consumer welfare, not assumptions that large firms are automatically harmful to competition, should be the core consideration of any antitrust action. The consumer welfare standard serves as the "good reason" in antitrust enforcement as it appropriately looks at the impact on consumers and economic efficiency. So far, it is not apparent that there has been a harm to consumer welfare and many technology companies continue to innovate and are bringing real benefits to consumers. At the same time, some Big Tech companies engage in "per se" uncompetitive conduct, such as Amazon Marketplace and Amazon Home Services, via scaled agreements that restrain free trade in violation of, inter alia, 18 U.S.C. § 1343; 15 U.S.C. § 1; 15 U.S.C. § 45. When agreements that restrain trade are scaled on the Internet, such acts can be reasonably prosecuted with criminal charges of multiple counts of wire fraud as an illegal activity that crosses interstate borders.

On July 9, 2021, President Joe Biden signed Executive Order 14036, "Promoting Competition in the American Economy", a sweeping array of initiatives across the executive branch. Related to Big Tech, the order established an executive branch-wide policy to more thoroughly scrutinize mergers involving Big Tech companies, with focus on the acquisition of new, potentially disruptive technology from smaller firms by the larger companies. The order also instructed the FTC to establish rules related to data collection and its use by Big Tech companies in promoting their own service.

European Union

In June 2020, the European Union opened two new antitrust investigations into practices by Apple. The first investigation focuses on issues including whether Apple is using its dominant position in the market to stifle competition using its music and book streaming services. The second investigation focuses on Apple Pay, which allows payment by Apple devices to brick and mortar vendors. Apple limits the ability of banks and other financial institutions to use the iPhones' near field radio frequency technology.

Fines are insufficient to deter anti-competitive practices by high tech giants, according to European Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager. Commissioner Vestager explained, "fines are not doing the trick. And fines are not enough because fines are a punishment for illegal behaviour in the past. What is also in our decision is that you have to change for the future. You have to stop what you're doing."

In September 2021, the United States and European Union began discussions of a joint approach to Big Tech regulation. The European Parliament reached an agreement to implement the Digital Markets Act in March 2022, which once it has been implemented by member states, would restrict what data Big Tech companies could collect from European users, require interoperability of social media messaging applications, and allow alternate app stores and payment systems for systems like Apple and Google. The EU also reached agreement to implement the Digital Services Act in April 2022, which would require tech companies to take steps to remove illegal content from their services, such as hate speech and child sexual abuse, and eliminate targeting of ads based on gender, race or religion as well as targeting ads at children. Both the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act were enacted by the EU in July 2022.

Opposition

Scott Galloway has criticized the companies for "avoid[ing] taxes, invad[ing] privacy, and destroy[ing] jobs", while Smyrnaios has described the group as an oligopoly, coming to dominate the online market through anti-competitive practices, ever-increasing financial power, and intellectual property law. He has argued that the current situation is the result of economic deregulation, globalization, and the failure of politicians to understand and respond to developments in technology.

Smyrnaios recommended developing academic analysis of the political economy of the Internet in order to understand the methods of domination and to criticize these methods in order to encourage opposition to that domination.

Use of externally generated content

On May 9, 2019, the Parliament of France passed a law intended to force GAMA to pay for related rights (the reuse of substantial amounts of text, photos or videos), to the publishers and news agencies of the original materials. The law is aimed at implementing Article 15 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market of the European Union.

Political debates

According to The Globe and Mail, criticism of Big Tech has come from both the left (progressives) and the right (conservatives). The Left has criticized Big Tech for "runaway profit-taking and concentration of wealth", while the Right has criticized Big Tech for having a "liberal bias". According to The New York Times, "The left generally argues that companies like Facebook and Twitter aren't doing enough to root out misinformation, extremism and hate on their platforms, while the right insists that tech companies are going so overboard in their content decisions that they're suppressing conservative political views." According to The Hill, libertarians are against government regulation of Big Tech due to their support for laissez-faire economics.

Accusations of inaction towards misinformation

Following Russian interference in the 2016 US election, Facebook was criticized for not doing enough to curb misinformation, and accused of downplaying its role in allowing misinformation to spread. Part of the controversy involved the Cambridge Analytica scandal and political data collection. In 2019, a Senate Intelligence Committee report criticized tech giants more generally for not responding strongly enough to misinformation, most Senate Intelligence reports regarding the subject focused on Meta and Twitter's role. 'Big tech' social media networks improved their response to fake accounts and influence operation trolls, and these initiatives received some praise compared to 2016.

In 2020 and 2021, social media giants have been frequently criticized for allowing COVID-19 misinformation to spread. According to Representatives Frank Pallone, Mike Doyle, and Jan Schakowsky, "Industry self-regulation has failed. We must begin the work of changing incentives driving social media companies to allow and even promote misinformation and disinformation." President Joe Biden criticized Facebook for allowing anti-vaccine propaganda to spread. Multiple social media platforms introduced more stringent moderation of health-related misinformation.

Human Rights Watch criticized Big Tech, primarily Meta's Facebook, for capturing the information market in developing countries where misinformation would rapidly spread to new internet users.

Accusations of censorship and election interference

The practice of banning of what is known as "hate speech" has also received public criticism as many of the targets tend to be conservatives. In July 2020, United States House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law held a congressional hearing of CEOs of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple and Facebook, where some members of the subcommittee raised concerns about alleged bias against conservatives on social media. U.S. Representative for Florida's 1st congressional district Matt Gaetz suggested that the CEO of Amazon Jeff Bezos should "divorce from the SPLC," due to the practice of forbidding donations to organizations which are designated as hate groups by the SPLC.

On November 5, 2020, U. S. President Donald Trump claimed "historic election interference from big money, big media and big tech" and labeled the Democratic Party as "party of the big donors, the big media, the big tech". Conservative paper Washington Times criticized Trump's claim of election fraud as without evidence. On January 6, 2021, during his speech before the crowd of protesters stormed the United States Capitol, Trump accused "Big Tech" of rigging elections and shadow banning conservatives, while promising to hold them accountable and work to "get rid of" Section 230. On January 11, after Trump's Twitter account was suspended, German Chancellor Angela Merkel's chief spokesman Steffen Seibert noted that Merkel found Twitter's halt of Trump's account "problematic", adding that legislators, not private companies, should decide on any necessary curbs to free expression if speech incites to violence.

According to a New York University report in February 2021, conservative claims of social media censorship could be a form of disinformation, since an analysis of available data indicated that the claims that right-wing views were censored was false. Nonetheless, the same report also recommended that social media platforms could be more transparent to assuage concerns of ideological censorship, even if those concerns are overblown. However, conservatives have argued that Facebook and Twitter limiting the spread of the Hunter Biden laptop controversy on their platforms that later turned out to be accurate "proves Big Tech's bias". There is also a fear of over-censoring. One example is the ban of the channel Right Wing Watch by YouTube, which was banned for showing far-right content with the explicit goal of exposing and warning about those views (the channel was later restored after a backlash). Separately, Human Rights Watch stated that, particularly on Facebook, excessive content removals meant the loss of important information such as the documentation of human rights abuses needed as evidence to serve justice.

Facebook is also accused of censoring progressive voices, like deleting political ads by Democratic senator Elizabeth Warren who called for increased regulation of Big Tech monopolists and for breaking up Facebook because of its monopoly and abuse of power. Warren accused the company of having the "ability to shut down a debate" and called for "a social media marketplace that isn't dominated by a single censor".

Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny criticized tech giants (specifically Apple and Google) for cooperating with a Russian government order to ban the Smart Voting app. In India, Facebook and Twitter were criticized for censoring social media in favour of the Indian government during the 2020–2021 Indian farmers' protest. The Wall Street Journal pointed out how Facebook regularly restricted content critical of the Indian government, but never any content by government supporters, no matter how false their claims.

Censorship against tech giants

The largest tech platforms have faced censorship themselves. Google have been banned in China since 2010, when they decided to leave the country after the Communist Party demanded censorship of search results. although an attempt at establishing Google China was made. Meta and Twitter have been banned in China since 2009. Microsoft's LinkedIn has been blocked in Russia since 2016. Russia also blocked access to Facebook and Twitter because of "disinformation" and "fake news" in 2022.

On March 21, 2022, Russia recognized Meta as an extremist organization, making Meta the first public company to be recognized as extremist in Russia.

Alternatives

Alt-tech is a group of websites, social media platforms, and Internet service providers that consider themselves alternatives to more mainstream offerings. In the 2010s and 2020s, some conservatives who were banned from other social media platforms, and their supporters, began to move toward alt-tech platforms. Alt-tech platforms have been criticized by researchers and journalists for providing a cover for far-right userbases and antisemitism.

Distributed social networks such as the fediverse, for microblogging based on the ActivityPub protocol, are decentralised networks, typically based on free and open-source software (FOSS) that aim at community moderation of content. In 2018, the fediverse was "a loose family of sites that promote unfettered interaction across servers or even services", intended to provide an alternative to the "walled gardens" of Big Tech social networks.

Gallery

Apple Park, the corporate headquarters of Apple in Cupertino, California

Microsoft Redmond campus, the corporate headquarters of Microsoft in Redmond, Washington

Amazon Spheres at the corporate headquarters of Amazon in Seattle, Washington

Googleplex, the corporate headquarters of Alphabet in Mountain View, California

Meta headquarters in Menlo Park, California