The history of virology – the scientific study of viruses and the infections they cause – began in the closing years of the 19th century. Although Louis Pasteur and Edward Jenner developed the first vaccines to protect against viral infections, they did not know that viruses existed. The first evidence of the existence of viruses came from experiments with filters that had pores small enough to retain bacteria. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovsky used one of these filters to show that sap from a diseased tobacco plant remained infectious to healthy tobacco plants despite having been filtered. Martinus Beijerinck called the filtered, infectious substance a "virus" and this discovery is considered to be the beginning of virology.

The subsequent discovery and partial characterization of bacteriophages by Frederick Twort and Félix d'Herelle further catalyzed the field, and by the early 20th century many viruses had been discovered. In 1926, Thomas Milton Rivers defined viruses as obligate parasites. Viruses were demonstrated to be particles, rather than a fluid, by Wendell Meredith Stanley, and the invention of the electron microscope in 1931 allowed their complex structures to be visualised.

Pioneers

Despite his other successes, Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) was unable to find a causative agent for rabies and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected using a microscope. In 1884, the French microbiologist Charles Chamberland (1851–1931) invented a filter – known today as the Chamberland filter – that had pores smaller than bacteria. Thus, he could pass a solution containing bacteria through the filter and completely remove them from the solution.

In 1876, Adolf Mayer, who directed the Agricultural Experimental Station in Wageningen, was the first to show that what he called "Tobacco Mosaic Disease" was infectious. He thought that it was caused by either a toxin or a very small bacterium. Later, in 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitry Ivanovsky (1864–1920) used a Chamberland filter to study what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus. His experiments showed that crushed leaf extracts from infected tobacco plants remain infectious after filtration. Ivanovsky suggested the infection might be caused by a toxin produced by bacteria, but did not pursue the idea.

In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck (1851–1931), a microbiology teacher at the Agricultural School in Wageningen repeated experiments by Adolf Mayer and became convinced that filtrate contained a new form of infectious agent. He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing and he called it a contagium vivum fluidum (soluble living germ) and re-introduced the word virus. Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by the American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley (1904–1971), who proved that they were in fact, particles. In the same year, 1898, Friedrich Loeffler (1852–1915) and Paul Frosch (1860–1928) passed the first animal virus through a similar filter and discovered the cause of foot-and-mouth disease.

The first human virus to be identified was the yellow fever virus. In 1881, Carlos Finlay (1833–1915), a Cuban physician, first conducted and published research that indicated that mosquitoes were carrying the cause of yellow fever, a theory proved in 1900 by commission headed by Walter Reed (1851–1902). During 1901 and 1902, William Crawford Gorgas (1854–1920) organised the destruction of the mosquitoes' breeding habitats in Cuba, which dramatically reduced the prevalence of the disease. Gorgas later organised the elimination of the mosquitoes from Panama, which allowed the Panama Canal to be opened in 1914. The virus was finally isolated by Max Theiler (1899–1972) in 1932 who went on to develop a successful vaccine.

By 1928 enough was known about viruses to enable the publication of Filterable Viruses, a collection of essays covering all known viruses edited by Thomas Milton Rivers (1888–1962). Rivers, a survivor of typhoid fever contracted at the age of twelve, went on to have a distinguished career in virology. In 1926, he was invited to speak at a meeting organised by the Society of American Bacteriology where he said for the first time, "Viruses appear to be obligate parasites in the sense that their reproduction is dependent on living cells."

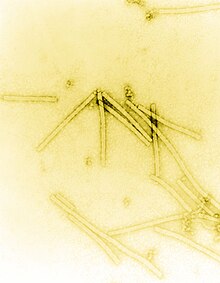

The notion that viruses were particles was not considered unnatural and fitted in nicely with the germ theory. It is assumed that Dr. J. Buist of Edinburgh was the first person to see virus particles in 1886, when he reported seeing "micrococci" in vaccine lymph, though he had probably observed clumps of vaccinia. In the years that followed, as optical microscopes were improved "inclusion bodies" were seen in many virus-infected cells, but these aggregates of virus particles were still too small to reveal any detailed structure. It was not until the invention of the electron microscope in 1931 by the German engineers Ernst Ruska (1906–1988) and Max Knoll (1887–1969), that virus particles, especially bacteriophages, were shown to have complex structures. The sizes of viruses determined using this new microscope fitted in well with those estimated by filtration experiments. Viruses were expected to be small, but the range of sizes came as a surprise. Some were only a little smaller than the smallest known bacteria, and the smaller viruses were of similar sizes to complex organic molecules.

In 1935, Wendell Stanley examined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it was mostly made of protein. In 1939, Stanley and Max Lauffer (1914) separated the virus into protein and nucleic acid, which was shown by Stanley's postdoctoral fellow Hubert S. Loring to be specifically RNA. The discovery of RNA in the particles was important because in 1928, Fred Griffith (c. 1879–1941) provided the first evidence that its "cousin", DNA, formed genes.

In Pasteur's day, and for many years after his death, the word "virus" was used to describe any cause of infectious disease. Many bacteriologists soon discovered the cause of numerous infections. However, some infections remained, many of them horrendous, for which no bacterial cause could be found. These agents were invisible and could only be grown in living animals. The discovery of viruses paved the way to understanding these mysterious infections. And, although Koch's postulates could not be fulfilled for many of these infections, this did not stop the pioneer virologists from looking for viruses in infections for which no other cause could be found.

Bacteriophages

Discovery

Bacteriophages are the viruses that infect and replicate in bacteria. They were discovered in the early 20th century, by the English bacteriologist Frederick Twort (1877–1950). But before this time, in 1896, the bacteriologist Ernest Hanbury Hankin (1865–1939) reported that something in the waters of the River Ganges could kill Vibrio cholerae – the cause of cholera. The agent in the water could be passed through filters that remove bacteria but was destroyed by boiling. Twort discovered the action of bacteriophages on staphylococci bacteria. He noticed that when grown on nutrient agar some colonies of the bacteria became watery. He collected some of these watery colonies and passed them through a Chamberland filter to remove the bacteria and discovered that when the filtrate was added to fresh cultures of bacteria, they in turn became watery. He proposed that the agent might be "an amoeba, an ultramicroscopic virus, a living protoplasm, or an enzyme with the power of growth".

Félix d'Herelle (1873–1949) was a mainly self-taught French-Canadian microbiologist. In 1917 he discovered that "an invisible antagonist", when added to bacteria on agar, would produce areas of dead bacteria. The antagonist, now known to be a bacteriophage, could pass through a Chamberland filter. He accurately diluted a suspension of these viruses and discovered that the highest dilutions (lowest virus concentrations), rather than killing all the bacteria, formed discrete areas of dead organisms. Counting these areas and multiplying by the dilution factor allowed him to calculate the number of viruses in the original suspension. He realised that he had discovered a new form of virus and later coined the term "bacteriophage". Between 1918 and 1921 d'Herelle discovered different types of bacteriophages that could infect several other species of bacteria including Vibrio cholerae. Bacteriophages were heralded as a potential treatment for diseases such as typhoid and cholera, but their promise was forgotten with the development of penicillin. Since the early 1970s, bacteria have continued to develop resistance to antibiotics such as penicillin, and this has led to a renewed interest in the use of bacteriophages to treat serious infections.

1920-1940: Early research D'Herelle travelled widely to promote the use of bacteriophages in the treatment of bacterial infections. In 1928, he became professor of biology at Yale and founded several research institutes. He was convinced that bacteriophages were viruses despite opposition from established bacteriologists such as the Nobel Prize winner Jules Bordet (1870–1961). Bordet argued that bacteriophages were not viruses but just enzymes released from "lysogenic" bacteria. He said "the invisible world of d'Herelle does not exist". But in the 1930s, the proof that bacteriophages were viruses was provided by Christopher Andrewes (1896–1988) and others. They showed that these viruses differed in size and in their chemical and serological properties. In 1940, the first electron micrograph of a bacteriophage was published and this silenced sceptics who had argued that bacteriophages were relatively simple enzymes and not viruses. Numerous other types of bacteriophages were quickly discovered and were shown to infect bacteria wherever they are found. Early research was interrupted by World War II. d'Herelle, despite his Canadian citizenship, was interned by the Vichy Government until the end of the war.

Modern era

Knowledge of bacteriophages increased in the 1940s following the formation of the Phage Group by scientists throughout the US. Among the members were Max Delbrück (1906–1981) who founded a course on bacteriophages at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Other key members of the Phage Group included Salvador Luria (1912–1991) and Alfred Hershey (1908–1997). During the 1950s, Hershey and Chase made important discoveries on the replication of DNA during their studies on a bacteriophage called T2. Together with Delbruck they were jointly awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses". Since then, the study of bacteriophages has provided insights into the switching on and off of genes, and a useful mechanism for introducing foreign genes into bacteria and many other fundamental mechanisms of molecular biology.

Plant viruses

In 1882, Adolf Mayer (1843–1942) described a condition of tobacco plants, which he called "mosaic disease" ("mozaïkziekte"). The diseased plants had variegated leaves that were mottled. He excluded the possibility of a fungal infection and could not detect any bacterium and speculated that a "soluble, enzyme-like infectious principle was involved". He did not pursue his idea any further, and it was the filtration experiments of Ivanovsky and Beijerinck that suggested the cause was a previously unrecognised infectious agent. After tobacco mosaic was recognized as a virus disease, virus infections of many other plants were discovered.

The importance of tobacco mosaic virus in the history of viruses cannot be overstated. It was the first virus to be discovered, and the first to be crystallised and its structure shown in detail. The first X-ray diffraction pictures of the crystallised virus were obtained by Bernal and Fankuchen in 1941. On the basis of her pictures, Rosalind Franklin discovered the full structure of the virus in 1955. In the same year, Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams showed that purified tobacco mosaic virus RNA and its coat protein can assemble by themselves to form functional viruses, suggesting that this simple mechanism was probably the means through which viruses were created within their host cells.

By 1935, many plant diseases were thought to be caused by viruses. In 1922, John Kunkel Small (1869–1938) discovered that insects could act as vectors and transmit virus to plants. In the following decade many diseases of plants were shown to be caused by viruses that were carried by insects and in 1939, Francis Holmes, a pioneer in plant virology, described 129 viruses that caused disease of plants. Modern, intensive agriculture provides a rich environment for many plant viruses. In 1948, in Kansas, US, 7% of the wheat crop was destroyed by wheat streak mosaic virus. The virus was spread by mites called Aceria tulipae.

In 1970, the Russian plant virologist Joseph Atabekov discovered that many plant viruses only infect a single species of host plant. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses now recognises over 900 plant viruses.

20th century

By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity, their ability to be filtered, and their requirement for living hosts. Up until this time, viruses had only been grown in plants and animals, but in 1906, Ross Granville Harrison (1870–1959) invented a method for growing tissue in lymph, and, in 1913, E Steinhardt, C Israeli, and RA Lambert used this method to grow vaccinia virus in fragments of guinea pig corneal tissue. In 1928, HB and MC Maitland grew vaccinia virus in suspensions of minced hens' kidneys. Their method was not widely adopted until the 1950s, when poliovirus was grown on a large scale for vaccine production. In 1941–42, George Hirst (1909–94) developed assays based on haemagglutination to quantify a wide range of viruses as well as virus-specific antibodies in serum.

Influenza

Although the influenza virus that caused the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic was not discovered until the 1930s, the descriptions of the disease and subsequent research has proved it was to blame. The pandemic killed 40–50 million people in less than a year, but the proof that it was caused by a virus was not obtained until 1933. Haemophilus influenzae is an opportunistic bacterium which commonly follows influenza infections; this led the eminent German bacteriologist Richard Pfeiffer (1858–1945) to incorrectly conclude that this bacterium was the cause of influenza. A major breakthrough came in 1931, when the American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture grew influenza and several other viruses in fertilised chickens' eggs. Hirst identified an enzymic activity associated with the virus particle, later characterised as the neuraminidase, the first demonstration that viruses could contain enzymes. Frank Macfarlane Burnet showed in the early 1950s that the virus recombines at high frequencies, and Hirst later deduced that it has a segmented genome.

Poliomyelitis

In 1949, John F. Enders (1897–1985) Thomas Weller (1915–2008), and Frederick Robbins (1916–2003) grew polio virus for the first time in cultured human embryo cells, the first virus to be grown without using solid animal tissue or eggs. Infections by poliovirus most often cause the mildest of symptoms. This was not known until the virus was isolated in cultured cells and many people were shown to have had mild infections that did not lead to poliomyelitis. But, unlike other viral infections, the incidence of polio – the rarer severe form of the infection – increased in the 20th century and reached a peak around 1952. The invention of a cell culture system for growing the virus enabled Jonas Salk (1914–1995) to make an effective polio vaccine.

Epstein–Barr virus

Denis Parsons Burkitt (1911–1993) was born in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, Ireland. He was the first to describe a type of cancer that now bears his name Burkitt's lymphoma. This type of cancer was endemic in equatorial Africa and was the commonest malignancy of children in the early 1960s. In an attempt to find a cause for the cancer, Burkitt sent cells from the tumour to Anthony Epstein (b. 1921) a British virologist, who along with Yvonne Barr and Bert Achong (1928–1996), and after many failures, discovered viruses that resembled herpes virus in the fluid that surrounded the cells. The virus was later shown to be a previously unrecognised herpes virus, which is now called Epstein–Barr virus. Surprisingly, Epstein–Barr virus is a very common but relatively mild infection of Europeans. Why it can cause such a devastating illness in Africans is not fully understood, but reduced immunity to virus caused by malaria might be to blame. Epstein–Barr virus is important in the history of viruses for being the first virus shown to cause cancer in humans.

Late 20th and early 21st century

The second half of the 20th century was the golden age of virus discovery and most of the 2,000 recognised species of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years. In 1946, bovine virus diarrhea was discovered, which is still possibly the most common pathogen of cattle throughout the world and in 1957, equine arterivirus was discovered. In the 1950s, improvements in virus isolation and detection methods resulted in the discovery of several important human viruses including varicella zoster virus, the paramyxoviruses, – which include measles virus, and respiratory syncytial virus – and the rhinoviruses that cause the common cold. In the 1960s more viruses were discovered. In 1963, the hepatitis B virus was discovered by Baruch Blumberg (b. 1925). Reverse transcriptase, the key enzyme that retroviruses use to translate their RNA into DNA, was first described in 1970, independently by Howard Temin and David Baltimore (b. 1938). This was important to the development of antiviral drugs – a key turning-point in the history of viral infections. In 1983, Luc Montagnier (b. 1932) and his team at the Pasteur Institute in France first isolated the retrovirus now called HIV. In 1989 Michael Houghton's team at Chiron Corporation discovered hepatitis C. New viruses and strains of viruses were discovered in every decade of the second half of the 20th century. These discoveries have continued in the 21st century as new viral diseases such as SARS and nipah virus have emerged. Despite scientists' achievements over the past one hundred years, viruses continue to pose new threats and challenges.