From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Criminology (from Latin crimen, "accusation", and Ancient Greek -λογία, -logia, from λόγος logos meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, political scientists, economists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, social workers, biologists, social anthropologists, as well as scholars of law.

Criminologists are the people working and researching the study

of crime and society's response to crime. Some criminologists examine

behavioral patterns of possible criminals. Generally, criminologists

conduct research and investigations, developing theories and analyzing

empirical patterns.

The interests of criminologists include the study of nature of crime and criminals, origins of criminal law, etiology

of crime, social reaction to crime, and the functioning of law

enforcement agencies and the penal institutions. It can be broadly said

that criminology directs its inquiries along three lines: first, it

investigates the nature of criminal law and its administration and

conditions under which it develops; second, it analyzes the causation of crime

and the personality of criminals; and third, it studies the control of

crime and the rehabilitation of offenders. Thus, criminology includes

within its scope the activities of legislative bodies, law-enforcement

agencies, judicial institutions, correctional institutions and

educational, private and public social agencies.

History of academic criminology

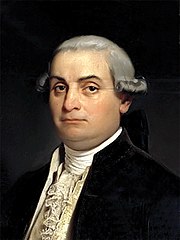

In the mid-18th century, criminology arose as social philosophers gave thought to crime and concepts of law. The term criminology was coined in 1885 by Italian law professor Raffaele Garofalo as Criminologia [it]. Later, French anthropologist Paul Topinard used the analogous French term Criminologie [fr]. Paul Topinard's major work appeared in 1879.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, scholars of

crime focused on reform of criminal law and not on the causes of crime. Scholars such as Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham were more concerned with the humanitarian aspects of dealing with criminals and reforming criminal laws.

Criminology grew substantially as a discipline in the first quarter of

the twentieth century. The first American textbook on criminology was

written in 1920 by sociologist Maurice Parmalee under the title Criminology.

Academic programs were developed for the specific purpose of training

students to be criminologists, but the development was rather slow.

From 1900 through to 2000 this field of research underwent three

significant phases in the United States: (1) Golden Age of Research

(1900–1930) which has been described as a multiple-factor approach, (2)

Golden Age of Theory (1930–1960) which endeavored to show the limits of

systematically connecting criminological research to theory, and (3) a

1960–2000 period, which was seen as a significant turning point for

criminology.

Schools of thought

There

were three main schools of thought in early criminological theory,

spanning the period from the mid-18th century to the mid-twentieth

century: Classical, Positivist, and Chicago.

These schools of thought were superseded by several contemporary

paradigms of criminology, such as the sub-culture, control, strain,

labelling, critical criminology, cultural criminology, postmodern criminology, feminist criminology and others discussed below.

Classical

The Classical school arose in the mid-18th century and has its basis in utilitarian philosophy. Cesare Beccaria, author of On Crimes and Punishments (1763–64), Jeremy Bentham (inventor of the panopticon), and other philosophers in this school argued:

- People have free will to choose how to act.

- The basis for deterrence is the idea humans are 'hedonists'

who seek pleasure and avoid pain, and 'rational calculators' who weigh

the costs and benefits of every action. It ignores the possibility of irrationality and unconscious drives as 'motivators'.

- Punishment

(of sufficient severity) can deter people from crime, as the costs

(penalties) outweigh the benefits, and severity of punishment should be

proportionate to the crime.

- The more swift and certain the punishment, the more effective as a deterrent to criminal behaviour.

This school developed during a major reform in penology when society began designing prisons for the sake of extreme punishment. This period also saw many legal reforms, the French Revolution, and the development of the legal system in the United States.

Positivist

The Positivist school

argues criminal behaviour comes from internal and external factors out

of the individual's control. Its key method of thought is that criminals

are born as criminals and not made into them;

this school of thought also supports theory of nature in the debate

between nature versus nurture. They also argue that criminal behavior is

innate and within a person. Philosophers within this school applied the

scientific method to study human behavior. Positivism comprises three

segments: biological, psychological and social positivism.

Biological positivism is the belief that these criminals and

their criminal behavior stem from "chemical imbalances" or

"abnormalities" within the brain or the DNA due to basic internal

"defects".

Psychological Positivism is the concept that criminal acts or the

people doing said crimes do them because of internal factors driving

them. It differs from biological positivism which says criminals are

born criminals, whereas the psychological perspective recognizes the

internal factors are results of external factors such as, but not

limited to, abusive parents, abusive relationships, drug problems, etc.

Social Positivism, which is often referred to as Sociological

Positivism, discusses the thought process that criminals are produced by

society. This school claims that low income levels, high

poverty/unemployment rates, and poor educational systems create and fuel

criminals and crimes.

Criminal personality

The

notion of having a criminal personality is derived from the school of

thought of psychological positivism. It essentially means that parts of

an individual's personality have traits that align with many of those

possessed by criminals, such as neuroticism, anti-social tendencies,

aggressive behaviors, and other factors. There is evidence of

correlation, but not causation, between these personality traits and

criminal actions.

Italian

Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), an Italian sociologist working in the late 19th century, is often called "the father of criminology". He was one of the key contributors to biological positivism and founded the Italian school of criminology. Lombroso took a scientific approach, insisting on empirical evidence for studying crime. He suggested physiological traits such as the measurements of cheekbones or hairline, or a cleft palate could indicate "atavistic" criminal tendencies. This approach, whose influence came via the theory of phrenology and by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, has been superseded. Enrico Ferri,

a student of Lombroso, believed social as well as biological factors

played a role, and believed criminals should not be held responsible

when factors causing their criminality were beyond their control.

Criminologists have since rejected Lombroso's biological theories since control groups were not used in his studies.

Sociological positivist

Sociological positivism suggests societal factors such as poverty, membership of subcultures, or low levels of education can predispose people to crime. Adolphe Quetelet

used data and statistical analysis to study the relationship between

crime and sociological factors. He found age, gender, poverty,

education, and alcohol consumption were important factors to crime. Lance Lochner performed three different research experiments, each one proving education reduces crime. Rawson W. Rawson used crime statistics to suggest a link between population density and crime rates, with crowded cities producing more crime. Joseph Fletcher and John Glyde read papers to the Statistical Society of London on their studies of crime and its distribution. Henry Mayhew used empirical methods and an ethnographic approach to address social questions and poverty, and gave his studies in London Labour and the London Poor. Émile Durkheim viewed crime as an inevitable aspect of a society with uneven distribution of wealth and other differences among people.

Differential association (sub-cultural)

Differential association (sub-cultural) posits that people learn crime through association. This theory was advocated by Edwin Sutherland,

who focused on how "a person becomes delinquent because of an excess of

definitions favorable to violation of law over definitions unfavorable

to violation of law."

Associating with people who may condone criminal conduct, or justify

crime under specific circumstances makes one more likely to take that

view, under his theory. Interacting with this type of "antisocial" peer is a major cause of delinquency. Reinforcing criminal behavior makes it chronic. Where there are criminal subcultures, many individuals learn crime, and crime rates swell in those areas.

Chicago

The Chicago school arose in the early twentieth century, through the work of Robert E. Park, Ernest Burgess, and other urban sociologists at the University of Chicago. In the 1920s, Park and Burgess identified five concentric zones that often exist as cities grow, including the "zone of transition", which was identified as the most volatile and subject to disorder. In the 1940s, Henry McKay and Clifford R. Shaw focused on juvenile delinquents,

finding that they were concentrated in the zone of transition. The

Chicago School was a school of thought developed that blames social

structures for human behaviors. This thought can be associated or used

within criminology, because it essentially takes the stance of defending

criminals and criminal behaviors. The defense and argument lies in the

thoughts that these people and their acts are not their faults but they

are actually the result of society (i.e. unemployment, poverty, etc.),

and these people are actually, in fact, behaving properly.

Chicago school sociologists adopted a social ecology

approach to studying cities and postulated that urban neighborhoods

with high levels of poverty often experience a breakdown in the social structure and institutions, such as family and schools. This results in social disorganization, which reduces the ability of these institutions to control behavior and creates an environment ripe for deviant behavior.

Other researchers suggested an added social-psychological link. Edwin Sutherland suggested that people learn criminal behavior from older, more experienced criminals with whom they may associate.

Theoretical perspectives used in criminology include psychoanalysis, functionalism, interactionism, Marxism, econometrics, systems theory, postmodernism, genetics, neuropsychology, evolutionary psychology, etc.

Social structure theories

This

theory is applied to a variety of approaches within the bases of

criminology in particular and in sociology more generally as a conflict theory

or structural conflict perspective in sociology and sociology of crime.

As this perspective is itself broad enough, embracing as it does a

diversity of positions.

Disorganization

Social disorganization theory is based on the work of Henry McKay and Clifford R. Shaw of the Chicago School.

Social disorganization theory postulates that neighborhoods plagued

with poverty and economic deprivation tend to experience high rates of population turnover.

This theory suggests that crime and deviance is valued within groups in

society, ‘subcultures’ or ‘gangs’. These groups have different values

to the social norm. These neighborhoods also tend to have high population heterogeneity. With high turnover, informal social structure often fails to develop, which in turn makes it difficult to maintain social order in a community.

Ecology

Since

the 1950s, social ecology studies have built on the social

disorganization theories. Many studies have found that crime rates are

associated with poverty, disorder, high numbers of abandoned buildings,

and other signs of community deterioration. As working and middle-class people leave deteriorating neighborhoods, the most disadvantaged portions of the population may remain. William Julius Wilson

suggested a poverty "concentration effect", which may cause

neighborhoods to be isolated from the mainstream of society and become

prone to violence.

Strain

Strain theory, also known as Mertonian Anomie, advanced by American sociologist Robert Merton,

suggests that mainstream culture, especially in the United States, is

saturated with dreams of opportunity, freedom, and prosperity—as Merton

put it, the American Dream. Most people buy into this dream, and it becomes a powerful cultural and psychological motivator. Merton also used the term anomie, but it meant something slightly different for him than it did for Durkheim. Merton saw the term as meaning a dichotomy

between what society expected of its citizens and what those citizens

could actually achieve. Therefore, if the social structure of

opportunities is unequal and prevents the majority from realizing the

dream, some of those dejected will turn to illegitimate means (crime) in

order to realize it. Others will retreat or drop out into deviant subcultures (such as gang members, or what he calls "hobos"). Robert Agnew developed this theory further to include types of strain which were not derived from financial constraints. This is known as general strain theory.

Subcultural

Following the Chicago school and strain theory, and also drawing on Edwin Sutherland's idea of differential association, sub-cultural theorists focused on small cultural groups fragmenting away from the mainstream to form their own values and meanings about life.

Albert K. Cohen tied anomie theory with Sigmund Freud's reaction formation idea, suggesting that delinquency among lower-class youths is a reaction against the social norms of the middle class.

Some youth, especially from poorer areas where opportunities are

scarce, might adopt social norms specific to those places that may

include "toughness" and disrespect for authority. Criminal acts may

result when youths conform to norms of the deviant subculture.

Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin suggested that delinquency can result from a differential opportunity for lower class youth.

Such youths may be tempted to take up criminal activities, choosing an

illegitimate path that provides them more lucrative economic benefits

than conventional, over legal options such as minimum wage-paying jobs available to them.

Delinquency tends to occur among the lower-working-class males

who have a lack of resources available to them and live in impoverished

areas, as mentioned extensively by Albert Cohen (Cohen, 1965). Bias has

been known to occur among law enforcement agencies, where officers tend

to place a bias on minority groups, without knowing for sure if they had

committed a crime or not. Delinquents may also commit crimes in order

to secure funds for themselves or their loved ones, such as committing

an armed robbery, as studied by many scholars (Briar & Piliavin).

British sub-cultural theorists focused more heavily on the issue of class,

where some criminal activities were seen as "imaginary solutions" to

the problem of belonging to a subordinate class. A further study by the

Chicago school looked at gangs and the influence of the interaction of

gang leaders under the observation of adults.

Sociologists such as Raymond D. Gastil have explored the impact of a Southern culture of honor on violent crime rates.

Control

Another approach is made by the social bond or social control theory. Instead of looking for factors that make people become criminal, these theories try to explain why people do not become criminal. Travis Hirschi

identified four main characteristics: "attachment to others", "belief

in moral validity of rules", "commitment to achievement", and

"involvement in conventional activities".

The more a person features those characteristics, the less likely he

or she is to become deviant (or criminal). On the other hand, if these

factors are not present, a person is more likely to become a criminal.

Hirschi expanded on this theory with the idea that a person with low self-control

is more likely to become criminal. As opposed to most criminology

theories, these do not look at why people commit crime but rather why

they do not commit crime.

A simple example: Someone wants a big yacht but does not have the

means to buy one. If the person cannot exert self-control, he or she

might try to get the yacht (or the means for it) in an illegal way,

whereas someone with high self-control will (more likely) either wait,

deny themselves of what want or seek an intelligent intermediate

solution, such as joining a yacht club to use a yacht by group

consolidation of resources without violating social norms.

Social bonds, through peers,

parents, and others can have a countering effect on one's low

self-control. For families of low socio-economic status, a factor that

distinguishes families with delinquent children, from those who are not

delinquent, is the control exerted by parents or chaperonage. In addition, theorists such as David Matza and Gresham Sykes argued that criminals are able to temporarily neutralize internal moral and social-behavioral constraints through techniques of neutralization.

Psychoanalytic

Psychoanalysis is a psychological theory (and therapy) which regards the unconscious mind, repressed memories and trauma, as the key drivers of behavior, especially deviant behavior. Sigmund Freud talks about how the unconscious desire for pain relates to psychoanalysis in his essay, Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

Freud suggested that unconscious impulses such as ‘repetition

compulsion’ and a ‘death drive’ can dominate a person's creativity,

leading to self-destructive behavior. Phillida Rosnick, in the article Mental Pain and Social Trauma,

posits a difference in the thoughts of individuals suffering traumatic

unconscious pain which corresponds to them having thoughts and feelings

which are not reflections of their true selves. There is enough

correlation between this altered state of mind and criminality to

suggest causation. Sander Gilman, in the article Freud and the Making of Psychoanalysis, looks for evidence in the physical mechanisms of the human brain and the nervous system

and suggests there is a direct link between an unconscious desire for

pain or punishment and the impulse to commit crime or deviant acts.

Symbolic interactionism

Symbolic interactionism draws on the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and George Herbert Mead, as well as subcultural theory and conflict theory.

This school of thought focused on the relationship between state,

media, and conservative-ruling elite and other less powerful groups. The

powerful groups had the ability to become the "significant other" in

the less powerful groups' processes of generating meaning.

The former could to some extent impose their meanings on the latter;

therefore they were able to "label" minor delinquent youngsters as

criminal. These youngsters would often take the label on board, indulge

in crime more readily, and become actors in the "self-fulfilling prophecy" of the powerful groups. Later developments in this set of theories were by Howard Becker and Edwin Lemert, in the mid-20th century. Stanley Cohen developed the concept of "moral panic" describing the societal reaction to spectacular, alarming social phenomena (e.g. post-World War 2 youth cultures like the Mods and Rockers in the UK in 1964, AIDS epidemic and football hooliganism).

Labeling theory

Labeling theory refers to an individual who is labeled by others in a

particular way. The theory was studied in great detail by Becker.

It was originally derived from sociology, but is regularly used in

criminological studies. When someone is given the label of a criminal

they may reject or accept it and continue to commit crime. Even those

who initially reject the label can eventually accept it as the label

becomes more well known, particularly among their peers. This stigma can

become even more profound when the labels are about deviancy, and it is

thought that this stigmatization can lead to deviancy amplification. Malcolm Klein conducted a test which showed that labeling theory affected some youth offenders but not others.

Traitor theory

At the other side of the spectrum, criminologist Lonnie Athens

developed a theory about how a process of brutalization by parents or

peers that usually occurs in childhood results in violent crimes in

adulthood. Richard Rhodes' Why They Kill

describes Athens' observations about domestic and societal violence in

the criminals' backgrounds. Both Athens and Rhodes reject the genetic

inheritance theories.

Rational choice theory

Rational choice theory is based on the utilitarian, classical school philosophies of Cesare Beccaria, which were popularized by Jeremy Bentham.

They argued that punishment, if certain, swift, and proportionate to

the crime, was a deterrent for crime, with risks outweighing possible

benefits to the offender. In Dei delitti e delle pene (On Crimes and Punishments, 1763–1764), Beccaria advocated a rational penology.

Beccaria conceived of punishment as the necessary application of the

law for a crime; thus, the judge was simply to confirm his or her

sentence to the law. Beccaria also distinguished between crime and sin, and advocated against the death penalty, as well as torture and inhumane treatments, as he did not consider them as rational deterrents.

This philosophy was replaced by the positivist and Chicago schools and was not revived until the 1970s with the writings of James Q. Wilson, Gary Becker's 1965 article Crime and Punishment and George Stigler's 1970 article The Optimum Enforcement of Laws.

Rational choice theory argues that criminals, like other people, weigh

costs or risks and benefits when deciding whether to commit crime and

think in economic terms. They will also try to minimize risks of crime by considering the time, place, and other situational factors.

Becker, for example, acknowledged that many people operate under a

high moral and ethical constraint but considered that criminals

rationally see that the benefits of their crime outweigh the cost, such

as the probability of apprehension and conviction, severity of

punishment, as well as their current set of opportunities. From the

public policy perspective, since the cost of increasing the fine is

marginal to that of the cost of increasing surveillance, one can conclude that the best policy is to maximize the fine and minimize surveillance.

With this perspective, crime prevention or reduction measures can be devised to increase the effort required to commit the crime, such as target hardening.

Rational choice theories also suggest that increasing risk and

likelihood of being caught, through added surveillance, law enforcement

presence, added street lighting, and other measures, are effective in

reducing crime.

One of the main differences between this theory and Bentham's

rational choice theory, which had been abandoned in criminology, is that

if Bentham considered it possible to completely annihilate crime

(through the panopticon),

Becker's theory acknowledged that a society could not eradicate crime

beneath a certain level. For example, if 25% of a supermarket's products

were stolen, it would be very easy to reduce this rate to 15%, quite

easy to reduce it until 5%, difficult to reduce it under 3% and nearly

impossible to reduce it to zero (a feat which the measures required

would cost the supermarket so much that it would outweigh the benefits).

This reveals that the goals of utilitarianism and classical liberalism have to be tempered and reduced to more modest proposals to be practically applicable.

Such rational choice theories, linked to neoliberalism, have been at the basics of crime prevention through environmental design and underpin the Market Reduction Approach to theft by Mike Sutton,

which is a systematic toolkit for those seeking to focus attention on

"crime facilitators" by tackling the markets for stolen goods that provide motivation for thieves to supply them by theft.

Routine activity theory

Routine activity theory, developed by Marcus Felson and Lawrence

Cohen, draws upon control theories and explains crime in terms of crime

opportunities that occur in everyday life.

A crime opportunity requires that elements converge in time and place

including a motivated offender, suitable target or victim, and lack of a

capable guardian.

A guardian at a place, such as a street, could include security guards

or even ordinary pedestrians who would witness the criminal act and

possibly intervene or report it to law enforcement.

Routine activity theory was expanded by John Eck, who added a fourth

element of "place manager" such as rental property managers who can take

nuisance abatement measures.

Biosocial theory

Biosocial criminology

is an interdisciplinary field that aims to explain crime and antisocial

behavior by exploring both biological factors and environmental

factors. While contemporary criminology has been dominated by

sociological theories, biosocial criminology also recognizes the

potential contributions of fields such as genetics, neuropsychology, and evolutionary psychology. Various theoretical frameworks such as evolutionary neuroandrogenic theory

have sought to explain trends in criminality through the lens of

evolutionary biology. Specifically, they seek to explain why criminality

is so much higher in men than in women and why young men are most

likely to exhibit criminal behavior. See also: genetics of aggression.

Aggressive behavior has been associated with abnormalities in three principal regulatory systems in the body: serotonin systems, catecholamine systems, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Abnormalities in these systems also are known to be induced by stress, either severe, acute stress or chronic low-grade stress.

Marxist

In 1968, young British sociologists formed the National Deviance Conference (NDC) group. The group was restricted to academics and consisted of 300 members. Ian Taylor, Paul Walton and Jock Young

– members of the NDC – rejected previous explanations of crime and

deviance. Thus, they decided to pursue a new Marxist criminological

approach. In The New Criminology, they argued against the biological "positivism" perspective represented by Lombroso, Hans Eysenck and Gordon Trasler.

According to the Marxist perspective on crime, "defiance is

normal – the sense that men are now consciously involved ... in assuring

their human diversity." Thus Marxists criminologists argued in support

of society in which the facts of human diversity, be it social or

personal, would not be criminalized.

They further attributed the processes of crime creation not to genetic

or psychological facts, but rather to the material basis of a given

society.

State crime is a distinct field of crimes that is studied by Marxist criminology

is These crimes are known to be some of the most costly to society in

terms of overall harm/injury. Supplying us with the causalities of genocides, environmental degradation, and war.

These are not crimes that occur out of contempt for their fellow man.

These are crimes of power to continue systems of control and hegemony

which allow state crime and state-corporate crime, along with state-corporate non-profit criminals, to continue governing people.

Convict

Convict

criminology is a school of thought in the realm of criminology. Convict

criminologists have been directly affected by the criminal justice system,

oftentimes having spent years inside the prison system. Researchers in

the field of convict criminology such as John Irwin and Stephan Richards

argue that traditional criminology can better be understood by those

who lived in the walls of a prison. Martin Leyva argues that "prisonization" oftentimes begins before prison, in the home, community, and schools.

According to Rod Earle, Convict Criminology started in the United

States after the major expansion of prisons in the 1970s, and the U.S

still remains the main focus for those who study convict criminology.

Queer

Queer criminology is a field of study that focuses on LGBT individuals and their interactions with the criminal justice system. The goals of this field of study are as follows:

- To better understand the history of LGBT individuals and the laws put against the community

- Why LGBT citizens are incarcerated and if or why they are arrested at higher rates than heterosexual and cisgender individuals

- How queer activists have fought against oppressive laws that criminalized LGBT individuals

- To conduct research and use it as a form of activism through education

Legitimacy of Queer criminology:

The value of pursuing criminology from a queer theorist

perspective is contested; some believe that it is not worth researching

and not relevant to the field as a whole, and as a result is a subject

that lacks a wide berth of research available. On the other hand, it

could be argued that this subject is highly valuable in highlighting how

LGBT individuals are affected by the criminal justice system. This

research also has the opportunity to "queer" the curriculum of

criminology in educational institutions by shifting the focus from

controlling and monitoring LGBT communities to liberating and protecting

them.

Cultural

Cultural criminology views crime and its control within the context of culture.

Ferrell believes criminologists can examine the actions of criminals,

control agents, media producers, and others to construct the meaning of

crime. He discusses these actions as a means to show the dominant role of culture.

Kane adds that cultural criminology has three tropes; village, city

street, and media, in which males can be geographically influenced by

society's views on what is broadcast and accepted as right or wrong.

The village is where one engages in available social activities.

Linking the history of an individual to a location can help determine

social dynamics.

The city street involves positioning oneself in the cultural area. This

is full of those affected by poverty, poor health and crime, and large

buildings that impact the city but not neighborhoods.

Mass media gives an all-around account of the environment and the

possible other subcultures that could exist beyond a specific

geographical area.

It was later that Naegler and Salman introduced feminist theory to cultural criminology and discussed masculinity and femininity, sexual attraction and sexuality, and intersectional themes.

Naegler and Salman believed that Ferrell's mold was limited and that

they could add to the understanding of cultural criminology by studying

women and those who do not fit Ferrell's mold.

Hayward would later add that not only feminist theory, but green theory

as well, played a role in the cultural criminology theory through the

lens of adrenaline, the soft city, the transgressive subject, and the

attentive gaze.

The adrenaline lens deals with rational choice and what causes a person

to have their own terms of availability, opportunity, and low levels of

social control.

The soft city lens deals with reality outside of the city and the

imaginary sense of reality: the world where transgression occurs, where

rigidity is slanted, and where rules are bent.

The transgressive subject refers to a person who is attracted to

rule-breaking and is attempting to be themselves in a world where

everyone is against them. The attentive gaze is when someone, mainly an ethnographer,

is immersed into the culture and interested in lifestyle(s) and the

symbolic, aesthetic, and visual aspects. When examined, they are left

with the knowledge that they are not all the same, but come to a

settlement of living together in the same space.

Through it all, sociological perspective on cultural criminology theory

attempts to understand how the environment an individual is in

determines their criminal behavior.

Relative deprivation

Relative deprivation

involves the process where an individual measures his or her own

well-being and materialistic worth against that of other people and

perceive that they are worse off in comparison.

When humans fail to obtain what they believe they are owed, they can

experience anger or jealousy over the notion that they have been wrongly

disadvantaged.

Relative deprivation was originally utilized in the field of sociology by Samuel A. Stouffer, who was a pioneer of this theory. Stouffer revealed that soldiers fighting in World War II measured their personal success by the experience in their units rather than by the standards set by the military.

Relative deprivation can be made up of societal, political, economic,

or personal factors which create a sense of injustice. It is not based

on absolute poverty,

a condition where one cannot meet a necessary level to maintain basic

living standards. Rather, relative deprivation enforces the idea that

even if a person is financially stable, he or she can still feel

relatively deprived. The perception of being relatively deprived can

result in criminal behavior and/or morally problematic decisions.

Relative deprivation theory has increasingly been used to partially

explain crime as rising living standards can result in rising crime

levels. In criminology, the theory of relative deprivation explains that

people who feel jealous and discontent of others might turn to crime to

acquire the things that they can not afford.

Rural

"Rural crime" redirects here. For illegal hunting or capturing of wild animals, see

Poaching.

Rural criminology is the study of crime trends outside of

metropolitan and suburban areas. Rural criminologists have used social

disorganization and routine activity theories. The FBI Uniform Crime

Report shows that rural communities have significantly different crime

trends as opposed to metropolitan and suburban areas. The crime in rural

communities consists predominantly of narcotic related crimes such as

the production, use, and trafficking of narcotics. Social

disorganization theory is used to examine the trends involving

narcotics.

Social disorganization leads to narcotic use in rural areas because of

low educational opportunities and high unemployment rates. Routine

activity theory is used to examine all low-level street crimes such as

theft.

Much of the crime in rural areas is explained through routine activity

theory because there is often a lack of capable guardians in rural

areas.

Public

Public criminology is a strand within criminology closely tied to ideas associated with "public sociology",

focused on disseminating criminological insights to a broader audience

than academia. Advocates of public criminology argue that criminologists

should be "conducting and disseminating research on crime, law, and

deviance in dialogue with affected communities."

Its goal is for academics and researchers in criminology to provide

their research to the public in order to inform public decisions and

policymaking. This allows criminologists to avoid the constraints of

traditional criminological research.

In doing so, public criminology takes on many forms, including media

and policy advising as well as activism, civic-oriented education,

community outreach, expert testimony, and knowledge co-production.

Types and definitions of crime

Both

the positivist and classical schools take a consensus view of crime:

that a crime is an act that violates the basic values and beliefs of

society. Those values and beliefs are manifested as laws that society

agrees upon. However, there are two types of laws:

- Natural laws

are rooted in core values shared by many cultures. Natural laws protect

against harm to persons (e.g. murder, rape, assault) or property

(theft, larceny, robbery), and form the basis of common law systems.

- Statutes are enacted by legislatures and reflect current cultural mores, albeit that some laws may be controversial, e.g. laws that prohibit cannabis use and gambling. Marxist criminology, conflict criminology, and critical criminology claim that most relationships between state and citizen are non-consensual and, as such, criminal law is not necessarily representative of public beliefs and wishes: it is exercised in the interests of the ruling or dominant class. The more right-wing criminologies tend to posit that there is a consensual social contract between state and citizen.

Therefore, definitions of crimes will vary from place to place, in

accordance to the cultural norms and mores, but may be broadly

classified as a blue-collar crime, corporate crime, organized crime, political crime, public order crime, state crime, state-corporate crime, and white-collar crime. However, there have been moves in contemporary criminological theory to move away from liberal pluralism, culturalism, and postmodernism by introducing the universal term "harm" into the criminological debate as a replacement for the legal term "crime".

Subtopics

Areas of study in criminology include: