The term serf, in the sense of an unfree peasant of tsarist Russia, is the usual English-language translation of krepostnoy krest'yanin (крепостной крестьянин) which meant an unfree person who, unlike a slave, historically could be sold only with the land to which they were "attached". Peter I ended slavery in Russia in 1723. Contemporary legal documents, such as Russkaya Pravda (12th century onwards), distinguished several degrees of feudal dependency of peasants.

Serfdom became the dominant form of relation between Russian peasants and nobility in the 17th century. Serfdom most commonly existed in the central and southern areas of the Tsardom of Russia and, from 1721, of the subsequent Russian Empire. Serfdom in Little Russia (parts of today central Ukraine), and other Cossack lands, in the Urals and in Siberia generally occurred rarely until, during the reign of Catherine the Great (r. 1762–1796), it spread to Ukraine; noblemen began to send their serfs into Cossack lands in an attempt to harvest their extensive untapped natural resources.

Only the Russian state and Russian noblemen had the legal right to own serfs, but in practice commercial firms sold Russian serfs as slaves – not only within Russia but even abroad (especially into Persia and the Ottoman Empire) as "students or servants". Those "students and servants" were in fact owned by rich people, sometimes even by rich serfs, who were not noblemen. Emperor Nicholas I banned the trade in African slaves in 1842, though there were almost no Russians who participated in it, but Russian serfs were still sold and bought.

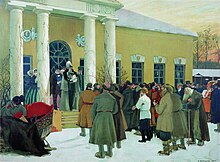

Emperor Alexander I (r. 1801–1825) wanted to reform the system but moved cautiously, liberating serfs in Estonia, Livonia (both 1816) and Courland (1817) only. New laws allowed all classes (except the serfs) to own land, a privilege previously confined to the nobility. Emperor Alexander II abolished serfdom in the emancipation reform of 1861, a few years later than Austria and other German states. Scholars have proposed multiple overlapping reasons to account for the abolition, including fear of a large-scale revolt by the serfs, the government's financial needs, changing cultural sensibilities, and the military's need for soldiers.

Terminology

The term muzhik, or moujik (Russian: мужи́к, IPA: [mʊˈʐɨk]) means "Russian peasant" when it is used in English. This word was borrowed from Russian into Western languages through translations of 19th-century Russian literature, describing Russian rural life of those times, and where the word muzhik was used to mean the most common rural dweller – a peasant – but this was only a narrow contextual meaning.

History

Origins

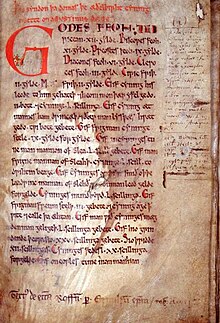

The origins of serfdom in Russia (крепостничество, krepostnichestvo) may be traced to the 12th century, when the exploitation of the so-called zakups on arable lands (ролейные (пашенные) закупы, roleyniye (pashenniye) zakupy) and corvée smerds (Russian term for corvée is барщина, barschina) was the closest to what is now known as serfdom. According to the Russkaya Pravda, a princely smerd had limited property and personal rights and his escheat was given to the prince.

Thirteenth to fifteenth centuries

In the 13th to 15th centuries, feudal dependency applied to a significant number of peasants, but serfdom as we know it was still not a widespread phenomenon. In the mid-15th century the right of certain categories of peasants in some votchinas to leave their master was limited to a period of one week before and after Yuri's Day (November 26). The Sudebnik of 1497 officially confirmed this time limit as universal for everybody and also established the amount of the "break-away" fee called pozhiloye (пожилое). The legal code of Ivan III of Russia, Sudebnik (1497), strengthened the dependency of peasants, statewide, and restricted their mobility. The Russians persistently battled against the successor states of the Golden Horde, chiefly the Khanate of Crimea. Annually the Russian population of the borderland suffered from Tatar invasions and slave raids and tens of thousands of noblemen protected the southern borderland (a heavy burden for the state), which slowed its social and economic development and expanded the taxation of peasantry.

Transition to full serfdom

The Sudebnik of 1550 increased the amount of pozhiloye and introduced an additional tax called za povoz (за повоз, or transportation fee), in case a peasant refused to bring the harvest from the fields to his master. A temporary (Заповедные лета, or forbidden years) and later an open-ended prohibition for peasants to leave their masters was introduced by the ukase of 1597 under the reign of Boris Godunov, which took away the peasants' right to free movement around Yuri's Day, binding the vast majority of the Russian peasantry in full serfdom. These also defined the so-called fixed years (Урочные лета, urochniye leta), or the 5-year time frame for search of the runaway peasants. In 1607, a new ukase defined sanctions for hiding and keeping the runaways: the fine had to be paid to the state and pozhiloye – to the previous owner of the peasant.

The Sobornoye Ulozhenie (Соборное уложение, "Code of Law") of 1649 gave serfs to estates, and in 1658, flight was made a criminal offense. Russian landowners eventually gained almost unlimited ownership over Russian serfs. The landowner could transfer the serf without land to another landowner while keeping the serf's personal property and family; however, the landowner had no right to kill the serf. About four-fifths of Russian peasants were serfs according to the censuses of 1678 and 1719; free peasants remained only in the north and north-east of the country.

Most of the dvoryane (nobles) were content with the long time frame for search of the runaway peasants. The major landowners of the country, however, together with the dvoryane of the south, were interested in a short-term persecution due to the fact that many runaways would usually flee to the southern parts of Russia. During the first half of the 17th century the dvoryane sent their collective petitions (челобитные, chelobitniye) to the authorities, asking for the extension of the "fixed years". In 1642, the Russian government established a 10-year limit for search of the runaways and 15-year limit for search for peasants taken away by their new owners.

The Sobornoye Ulozhenie introduced an open-ended search for those on the run, meaning that all of the peasants who had fled from their masters after the census of 1626 or 1646–1647 had to be returned. The government would still introduce new time frames and grounds for search of the runaways after 1649, which applied to the peasants who had fled to the outlying districts of the country, such as regions along the border abatises called zasechniye linii (засечные линии) (ukases of 1653 and 1656), Siberia (ukases of 1671, 1683 and 1700), Don (1698) etc. The dvoryane constantly demanded that the search for the runaways be sponsored by the government. The legislation of the second half of the 17th century paid much attention to the means of punishment of the runaways.

Serfdom was hardly efficient; serfs and nobles had little incentive to improve the land. However, it was politically effective. Nobles rarely challenged the tsar for fear of provoking a peasant uprising. Serfs were often given lifelong tenancy on their plots, so they tended to be conservative as well. The serfs took little part in uprisings against the empire as a whole; it was the Cossacks and nomads who rebelled initially and recruited serfs into rebel armies. But many landowners died during serf uprisings against them. The revolutions of 1905 and 1917 happened after serfdom's abolition.

Rebellions

There were numerous rebellions against this bondage, most often in conjunction with Cossack uprisings, such as the uprisings of Ivan Bolotnikov (1606–07), Stenka Razin (1667–71), Kondraty Bulavin (1707–09) and Yemelyan Pugachev (1773–75). While the Cossack uprisings benefited from disturbances among the peasants, and they in turn received an impetus from Cossack rebellion, none of the Cossack movements were directed against the institution of serfdom itself. Instead, peasants in Cossack-dominated areas became Cossacks during uprisings, thus escaping from the peasantry rather than directly organizing peasants against the institution. Rich Cossacks owned serfs themselves. Between the end of the Pugachev rebellion and the beginning of the 19th century, there were hundreds of outbreaks across Russia, and there was never a time when the peasantry was completely quiescent.

Slaves and serfs

As a whole, serfdom both came and remained in Russia much later than in other European countries. Slavery remained a legally recognized institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter the Great abolished slavery and converted the slaves into serfs. This was relevant more to household slaves because Russian agricultural slaves were formally converted into serfs earlier in 1679.

Formal conversion to serf status and the later ban on the sale of serfs without land did not stop the trade in household slaves; this trade merely changed its name. The private owners of the serfs regarded the law as a mere formality. Instead of "sale of a peasant" the papers would advertise "servant for hire" or similar.

By the eighteenth century, the practice of selling serfs without land had become commonplace. Owners had absolute control over their serfs' lives, and could buy, sell and trade them at will, giving them as much power over serfs as Americans had over chattel slaves, though owners did not always choose to exercise their powers over serfs to the fullest extent.

The official estimate is that 23 million Russians were privately owned, 18.3 million were in state ownership and another 900,000 serfs were under the Tsar's patronage (udelnye krestiane) before the Great Emancipation of 1861.

One particular source of indignation in Europe was Kolokol published in London, England (1857–65) and Geneva (1865–67). It collected many cases of horrendous physical, emotional and sexual abuse of the serfs by the landowners.

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

Peter III created two measures in 1762 that influenced the abolition of serfdom. He ended mandatory military service for nobles with the abolition of compulsory noble state service. This provided a rationale to end serfdom. Second, was the secularization of the church estates, which transferred its peasants and land to state jurisdiction. In 1775 measures were taken by Catherine II to prosecute estate owners for the cruel treatment of serfs. These measures were strengthened in 1817 and the late 1820s. There were even laws that required estate owners to help serfs in time of famine, which included grain to be kept in reserve. These policies failed to aid famines in the early nineteenth century due to estate owner negligence.

Tsar Alexander I and his advisors quietly discussed the options at length. Obstacles included the failure of abolition in Austria and the political reaction against the French Revolution. Cautiously, he freed peasants from Estonia and Latvia and extended the right to own land to most classes of subjects, including state-owned peasants, in 1801 and created a new social category of "free agriculturalist", for peasants voluntarily emancipated by their masters, in 1803. The great majority of serfs were not affected.

The Russian state also continued to support serfdom due to military conscription. The conscripted serfs dramatically increased the size of the Russian military during the war with Napoleon. With a larger military Russia achieved victory in the Napoleonic Wars and Russo-Persian Wars; this did not change the disparity between Russia and Western Europe, who were experiencing agricultural and industrial revolutions. Compared to Western Europe it was clear that Russia was at an economic disadvantage. European philosophers during the Age of Enlightenment criticized serfdom and compared it to medieval labor practices which were almost non-existent in the rest of the continent. Most Russian nobles were not interested in change toward western labor practices that Catherine the Great proposed. Instead they preferred to mortgage serfs for profit. Napoleon did not touch serfdom in Russia. What the reaction of the Russian peasantry would have been if he had lived up to the traditions of the French Revolution, bringing liberty to the serfs, is an intriguing question. In 1820, 20% of all serfs were mortgaged to state credit institutions by their owners. This was increased to 66% in 1859.

Bourgeois were allowed to own serfs 1721–62 and 1798–1816; this was to encourage industrialisation. In 1804, 48% of Russian factory workers were serfs, 52% in 1825. Landless serfs rose from 4.14% in 1835 to 6.79% in 1858. They received no land in the emancipation. Landlords deliberately increased the number of domestic serfs when they anticipated serfdom's demise. In 1798, Ukrainian landlords were banned from selling serfs apart from land. In 1841, landless nobles were banned also.

Increasingly in the 18th century Russian peasants were escaping from Russia to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (where once harsh serfdom conditions were improving) in significant enough numbers to become a major concern for the Russian Government and sufficient to play a role in its decision to partition the Commonwealth (one of the reasons Catherine II gave for the partition of Poland was the fact that thousands of peasants escaped from Russia to Poland to seek a better fate".) Until the partitions solved this problem, Russian armies raided territories of the Commonwealth, officially to recover the escapees, but in fact kidnapping many locals.

Abolition

In 1816, 1817, and 1819 serfdom was abolished in Estland, Courland, and Livonia respectively. However all the land stayed in noble hands and labor rent lasted till 1868. It was replaced with landless laborers and sharecropping (halbkörner). Landless workers had to ask permission to leave an estate.

The nobility was too weak to oppose the emancipation of the serfs. In 1820 a fifth of the serfs were mortgaged, half by 1842. By 1859, a third of noble's estates and two thirds of their serfs were mortgaged to noble banks or the state. The nobility was also weakened by the scattering of their estates, lack of primogeniture, and the high turnover and mobility from estate to estate.

The Tsar's aunt Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna played a powerful role backstage in the years 1855 to 1861. Using her close relationship with her nephew Alexander II, she supported and guided his desire for emancipation, and helped mobilize the support of key advisors.

In 1861 Alexander II freed all serfs in a major agrarian reform, stimulated in part by his view that "it is better to liberate the peasants from above" than to wait until they won their freedom by risings "from below".

Serfdom was abolished in 1861, but its abolition was achieved on terms not always favorable to the peasants and served to increase revolutionary pressures. Between 1864 and 1871 serfdom was abolished in Georgia. In Kalmykia serfdom was abolished only in 1892.

The serfs had to work for the landlord as usual for two years. The nobles kept nearly all the meadows and forests, had their debts paid by the state while the ex serfs paid 34% over the market price for the shrunken plots they kept. This figure was 90% in the northern regions, 20% in the black earth region but zero in the Polish provinces. In 1857, 6.79% of serfs were domestic, landless servants who stayed landless after 1861. Only Polish and Romanian domestic serfs got land. 90% of the serfs who got larger plots were in Congress Poland where the Tsar wanted to weaken the szlachta. The rest were in the barren north and in Astrakhan. In the whole Empire, peasant land declined 4.1%, 13.3% outside the ex Polish zone and 23.3% in the 16 black earth provinces. These redemption payments were not abolished till January 1, 1907.

Impact

A 2018 study in the American Economic Review found "substantial increases in agricultural productivity, industrial output, and peasants' nutrition in Imperial Russia as a result of the abolition of serfdom in 1861".

Serf society

Labour and obligations

In Russia, the terms barshchina (барщина) or boyarshchina (боярщина), refer to the obligatory work that the serfs performed for the landowner on his portion of the land (the other part of the land, usually of a poorer quality, the peasants could use for themselves). Sometimes the terms are loosely translated by the term corvée. While no official government regulation to the extent of barshchina existed, a 1797 ukase by Paul I of Russia described a barshchina of three days a week as normal and sufficient for the landowner's needs.

In the black earth region, 70% to 77% of the serfs performed barshchina; the rest paid levies (obrok).

Marriage and family life

The Russian Orthodox Church had many rules regarding marriage that were strictly observed by the population. For example, marriage was not allowed to take place during times of fasting, the eve or day of a holiday, during the entire week of Easter, or for two weeks after Christmas. Before the abolition of serfdom in 1861, marriage was strictly prohibited on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. Because of these firm rules most marriages occurred in the months of January, February, October, and November. After the emancipation the most popular marrying months were July, October, and November.

Imperial laws were very particular with the age in which serfs could marry. The minimum age to marry was 13 years old for women, and 15 for men. After 1830 the female and male ages were raised to 16 and 18 respectively. To marry over the age of 60, the serf had to receive permission, but marriage over the age of 80 was forbidden. The Church also did not approve marriages with large age differences.

Landowners were interested in keeping all of their serfs and not losing workers to marriages on other estates. Prior to 1812 serfs were not allowed to marry serfs from other estates. After 1812 the rules relaxed slightly, but in order for a family to give their daughter to a husband in another estate they had to apply and present information to their landowner ahead of time. If a serf wanted to marry a widow, then emancipation and death certificates were to be handed over and investigated for authenticity by their owner before a marriage could take place.

Before and after the abolition of serfdom, Russian peasant families were patriarchal. Marriage was important for families economically and socially. Parents were in charge of finding suitable spouses for their children in order to help the family. The bride's parents were concerned with the social and material benefits they would gain in the alliance between the two families. Some also took into consideration their daughter's future quality of life and how much work would be required of her. The groom's parents would be concerned about economical factors such as the size of the dowry as well as the bride's decency, modesty, obedience, ability to do work, and family background. Upon marriage, the bride came to live with her new husband and his family, so she needed to be ready to assimilate and work hard.

Serfs looked highly upon early marriage because of increased parental control. At a younger age there is less chance of the individual falling in love with someone other than whom his or her parents chose. There is also increased assurance of chastity, which was more important for women than men. The average age of marriage for women was around 19 years old.

During serfdom, when the head of the house was being disobeyed by their children they could have the master or landowner step in. After the emancipation of serfs in 1861, the household patriarch lost some of his power, and could no longer receive the landowner's help. The younger generations now had the freedom to work off their estates; some even went to work in factories. These younger peasants had access to newspapers and books, which introduced them to more radical ways of thinking. The ability to work outside of the household gave the younger peasants independence as well as a wage to do with what they wanted. Agricultural and domestic jobs were a group effort, so the wage went to the family. The children who worked industrial jobs gave their earnings to their family as well, but some used it as a way to gain a say in their own marriages. In this case some families allowed their sons to marry whom they chose as long as the family was in similar economic standing as their own. No matter what, parental approval was required in order to make a marriage legal.

Distribution of property and duties between the spouses

According to a study completed in the late 1890s by the ethnographer Olga Petrovna Semyonova-Tian-Shanskaia, husband and wife had different duties in the household. In regards to ownership, the husband assumed the property plus any funds required to make additions to the property. Additions included fence, barns, and wagons. While primary purchasing power belonged to the husband, the wife was expected to buy certain items. She was also expected to buy household items such as bowls, plates, pots, barrels and various utensils. Wives were also required to purchase cloth and make clothes for the family by spinning and using a dontse. Footwear was the husband's responsibility - he made bast shoes and felt boots for the family. As for crops, it was expected for men to sow and women to harvest. A common crop harvested by serfs in the Black Earth Region was flax. Husbands owned most of the livestock, such as pigs and horses. Cows were the property of the husband, but were usually in the wife's possession. Chickens were considered to be the wife's property, while sheep was common property for the family. The exception was when the wife owned sheep through a dowry (sobinki).

Material culture

Typical Russian serf clothing included the zipun (Russian: зипун, a collarless kaftan) and the smock.

A 19th-century report noted: "Every Russian peasant, male and female, wears cotton clothes. The men wear printed shirts and trousers, and the women are dressed from head to foot in printed cotton also."

The extent of serfdom in Russia

By the mid-19th century, peasants composed a majority of the population, and according to the census of 1857, the number of private serfs was 23.1 million out of 62.5 million citizens of the Russian empire, 37.7% of the population.

The exact numbers, according to official data, were: entire population 60909309; peasantry of all classes 49486665; state peasants 23138191; peasants on the lands of proprietors 23022390; peasants of the appanages and other departments 3326084. State peasants were considered personally free, but their freedom of movement was restricted.

| Estate of | 1700 | 1861 |

|---|---|---|

| >500 serfs | 26 | 42 |

| 100–500 | 33 | 38 |

| 1–100 | 41 | 20 |

| 1777 | 1834 | 1858 |

|---|---|---|

| 83 | 84 | 78 |

Russian serfdom depended entirely on the traditional and extensive technology of the peasantry. Yields remained low and stationary throughout most of the 19th century. Any increase in income drawn from agriculture was largely through increasing land area and extensive grain raising by means of exploitation of the peasant labor, that is, by burdening the peasant household still further.

| No. of serfs | in 1777 (%) | in 1859 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| >1000 | 1.1 | |

| 501–1000 | 2 | |

| 101–500 | 16 (>100) | 18 |

| 21–100 | 25 | 35.1 |

| 0–20 | 59 | 43.8 |

% peasants enserfed in each province, 1860

>55%: Kaluga Kyiv Kostroma Kutais Minsk Mogilev Nizhny Novgorod Podolia Ryazan Smolensk Tula Vitebsk Vladimir Volhynia Yaroslavl

36–55%: Chernigov Grodno Kovno Kursk Moscow Novgorod Oryol Penza Poltava Pskov Saratov Simbirsk Tambov Tver Vilna

16–35%: Don Ekaterinoslav Kharkov Kherson Kuban Perm Tiflis Vologda Voronezh

In the Central Black Earth Region 70–77% of the serfs performed labour services (barshchina), the rest paid rent (obrok). Owing to the high fertility, 70% of Russian cereal production in the 1850s was here. In the seven central provinces, 1860, 67.7% of the serfs were on obrok.