Climate security refers to the national and international security risks induced, directly or indirectly, by changes in climate patterns. It is a concept that summons the idea that climate-related change amplifies existing risks in society that endangers the security of humans, ecosystems, economy, infrastructure and societies. Climate-related security risks have far-reaching implications for the way the world manages peace and security. Climate actions to adapt and mitigate impacts can also have a negative effect on human security if mishandled.

Climate change has the potential to exacerbate existing tensions or create new ones – serving as a threat multiplier. It can be a catalyst for violent conflict and a threat to international security. A meta-analysis of over 50 quantitative studies that examine the link between climate and conflict found that "for each 1 standard deviation (1σ) change in climate toward warmer temperatures or more extreme rainfall, median estimates indicate that the frequency of interpersonal violence rises 4% and the frequency of intergroup conflict rises 14%." The IPCC has suggested that the disruption of environmental migration may serve to exacerbate conflicts, though they are less confident of the role of increased resource scarcity. Of course, climate change does not always lead to violence, and conflicts are often caused by multiple interconnected factors.

A variety of experts have warned that climate change may lead to increased conflict. The Military Advisory Board, a panel of retired U.S. generals and admirals, predicted that global warming will serve as a "threat multiplier" in already volatile regions. The Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Center for a New American Security, two Washington think tanks, have reported that flooding "has the potential to challenge regional and even national identities," leading to "armed conflict over resources." They indicate that the greatest threat would come from "large-scale migrations of people – both inside nations and across existing national borders." However, other researchers have been more skeptical: One study found no statistically meaningful relationship between climate and conflict using data from Europe between the years 1000 and 2000.

The link between climate change and security is a concern for authorities across the world, including United Nations Security Council and the G77 group of developing nations. Climate change's impact as a security threat is expected to hit developing nations particularly hard. In Britain, Foreign Secretary Margaret Beckett has argued that "An unstable climate will exacerbate some of the core drivers of conflict, such as migratory pressures and competition for resources." The links between the human impact of climate change and the threat of violence and armed conflict are particularly important because multiple destabilizing conditions are affected simultaneously.

Background

Climate security refers to the security risks induced, directly or indirectly, by changes in climate patterns. Climate change has been identified as a severe-to-catastrophic threat to international security in the 21st century by multiple risk and security reports. The 2020 Global Catastrophic Risks report, issued by the Global Challenges Foundation, concluded that climate change has a high likelihood to end civilization. 70% of international governments consider climate change to be a national security issue. Policy interest in climate security risks has grown rapidly and affects the policy agenda in relation to, among other questions, food and energy security, migration policy, and diplomatic efforts. Climate change is a global challenge which will affect all countries in the long-term as the impact of climate change is spread unevenly across different regions. However, there may a disproportionally harsher effect in fragile contexts and/or socially vulnerable and marginalized groups.

The 2018 Worldwide Threat Assessment report states:

The past 115 years have been the warmest period in the history of modern civilization, and the past few years have been the warmest years on record. Extreme weather events in a warmer world have the potential for greater impacts and can compound with other drivers to raise the risk of humanitarian disasters, conflict, water and food shortages, population migration, labor shortfalls, price shocks, and power outages. Research has not identified indicators of tipping points in climate-linked Earth systems, suggesting a possibility of abrupt climate change.

According to studies on climate security, it is often difficult to determine whether security and conflict issues in many countries and regions may occur, or can be attributed to climate change or climate related issues due to the presence of many factors such as ethnic tension, regional resolution tactics to issues, and outside powers placing pressures on countries being the possible reason for the conflict.

Academia

Within academia, climate security is part of environmental security and was first mentioned in the Brundtland Report in 1987. Thirty years later, experts and scientists in fields such as politics, diplomacy, environment and security have used this concept in an increasing frequency. There is high agreement that climate change intimidates security where the term ‘security’ can refer to a broad range of securities involving national, international and Human Security. Human Security is the most fragile as it can be compromised in order to protect national or international security.

Scholars analyzing conflicts with a climate security rendering have long argued that climate change can adversely affect security and international stability. Research has examined ‘indirect pathways between climate stress and conflict’ — through factors like economic growth, food price shock and forced displacement apart from other types of shock such as: income and livelihood shock (with the accompanying caveats in the table). Climate change can threaten human security by impacting economic growth, food price stock, undermining livelihoods, and prompting displacement. Moreover, there has been reports of collapse of pastoral societies, terrorist groups seeking recruits in dehydrated lands, and flooding ultimately feeding anti-government sentiments. Unstable regions appear to be incapable of surviving climate change-related stresses; instead creating conditions for radicalization, poverty and violent conflict. Scholars of climate security can analyze the chronological order of an escalation, where a changing environment or climate change can be an underlying variable. It is a complex interplay of many political and socio-economical factors where climate change is considered a risk-or threat-multiplier.

During the 70's and 80's the Jason advisory group, concerned with security, conducted research on climate change. Climate change has been identified as a threat multiplier, which can exacerbate existing threats. A 2013 meta-analysis of 60 previous peer-reviewed studies, and 45 data sets concluded that, "climate change intensifies natural resource stresses in a way that can increase the likelihood of livelihood devastation, state fragility, human displacement, and mass death."

In the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), The Pentagon stated: "The QDR will set a long-term course for DOD as it assesses the threats and challenges that the nation faces and re-balances DOD's strategies, capabilities, and forces to address today's conflicts and tomorrow's threats." and " "As greenhouse gas emissions increase, sea levels are rising, average global temperatures are increasing, and severe weather patterns are accelerating [...] Climate change may exacerbate water scarcity and lead to sharp increases in food costs. The pressures caused by climate change will influence resource competition while placing additional burdens on economies, societies, and governance institutions around the world. These effects are threat multipliers that will aggravate stressors abroad such as poverty, environmental degradation, political instability, and social tensions – conditions that can enable terrorist activity and other forms of violence." Climate scientist Michael E. Mann stated in his commentary to the 2018 global heat wave that climate change is a national security nightmare.

Impact

A report in 2003 by Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall looked at potential implications from climate-related scenarios for the national security of the United States, and concluded, "We have created a climate change scenario that although not the most likely, is plausible, and would challenge United States national security in ways that should be considered immediately." Among the findings were:

"There is a possibility that this gradual global warming could lead to a relatively abrupt slowing of the ocean's thermohaline conveyor, which could lead to harsher winter weather conditions, sharply reduced soil moisture, and more intense winds in certain regions that currently provide a significant fraction of the world's food production. With inadequate preparation, the result could be a significant drop in the human carrying capacity of the Earth's environment."

Researchers studying ancient climate patterns (paleoclimatology) noted in a 2007 study:

We show that long-term fluctuations of war frequency and population changes followed the cycles of temperature change. Further analyses show that cooling impeded agricultural production, which brought about a series of serious social problems, including price inflation, then successively war outbreak, famine, and population decline.

A 2013 review by the U.S. National Research Council assessed the implications of abrupt climate change, including implications for the physical climate system, natural systems, or human systems. The authors noted, "A key characteristic of these changes is that they can come faster than expected, planned, or budgeted for, forcing more reactive, rather than proactive, modes of behavior." A 2018 meta study cited cascading tipping elements, which could trigger self-reinforcing feedbacks that progress even when man-made emissions are reduced, and which could eventually establish a new hothouse climate state. The authors noted, "If the threshold is crossed, the resulting trajectory would likely cause serious disruptions to ecosystems, society, and economies."

Health

Studies identified uptake in mortality due to extreme heat waves. Extreme heat conditions can overcome the human capacity to thermo regulate; future scenarios with rising emissions could expose about 74% of the world population for at least twenty days per year to lethal heat events.

Psychological impacts

A 2011 article in the American Psychologist identified three classes of psychological impacts from global climate change:

- Direct - "Acute or traumatic effects of extreme weather events and a changed environment"

- Indirect - "Threats to emotional well-being based on observation of impacts and concern or uncertainty about future risks"

- Psychosocial - "Chronic social and community effects of heat, drought, migrations, and climate-related conflicts, and postdisaster adjustment"

Consequences of psychosocial impacts caused by climate change include: increase in violence, intergroup conflict, displacement and relocation and socioeconomic disparities. Based on research, there is a causal relationship between heat and violence and that any increase in average global temperature is likely to be accompanied by an increase in violent aggression.

Conflicts

The secondary impacts of climate hazards could be even more dangerous. Chief among them is an increased risk of armed conflict in places where established social orders and populations are disrupted. The risk will rise even more where climate effects compound social instability, reduce access to basic necessities, undermine fragile governments and economies, damage vital infrastructure, and lower agricultural production.

U.S. Army Climate Strategy

February 2022

Since climate change has serious and broad implications for societies and human livelihoods, the potential security consequences are far-reaching and complex. The topic started to receive major attention in 2007 when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Al Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for their efforts to mitigate climate change. In the same year, the UN Security Council held its first debate on climate change and security, with follow-up debates on the topic in 2012, 2018, 2019 and 2020. In an early study on the topic, the German Advisory Council on Global Change identified four pathways potentially connecting climate change to conflict: degradation of freshwater resources, food insecurity, an increasing frequency and intensity of natural disasters, and increasing or changing migration patterns. These factors can reportedly increase the risk of violent conflict by, for instance, changing opportunity structures for violence (e.g., when states are weakened or deprived individuals can be recruited by armed groups more easily) or exacerbating the grievances of affected populations.

In a 2016 article, published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the author suggested that conflict over climate-related water issues could lead to nuclear conflict, involving Kashmir, India and Pakistan. But while some scholars agree that climate change are unlikely to have major impacts on the nature of interstate wars, concerns have been raised about its impacts on civil wars and communal conflicts. Based on a meta-analysis of 60 studies, Hsiang, Burke and Miguel conclude that warmer temperatures and more extreme rainfall could increase interpersonal violence by 4%, and intergroup conflict by 14% (median estimates). However, their results have been disputed by other researchers as being not sufficiently robust to alternative model specifications. Recent studies have been more careful and agree that climate-related disasters (including heatwaves, droughts, storms and floods) modestly increase armed conflict risks, but only in the presence of contextual factors like agricultural dependence, insufficient infrastructure or the political exclusion of ethnic groups. Climate change is therefore rather a "risk multiplier" that amplifies existing risks of conflict. In line with this and other reviews of the topic, an expert assessment published 2019 in Nature concludes that between 3% and 20% of intrastate, armed conflict risks in the previous century were affected by climate-related factors, but that other drivers of conflict are far more important.

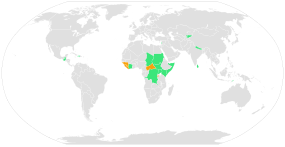

The expert assessment itself notes that major knowledge gaps and uncertainties continue to exist in the research field, especially regarding the pathways connecting climate change to conflict risk. Selby argues that the assessment ignores critical or constructivist approaches. Indeed, there are a number of studies that criticize how climate-conflict research is based on a deterministic and conflict-oriented worldview and that findings of statistical studies on the topic are based on problematic models and biased datasets. Existing research also predominantly focuses on a few, well-known and already conflict-ridden regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. This raises questions about sampling biases as well as implications for less-considered regions like Latin America and the Pacific, with topics such as peaceful adaptation and environmental peacebuilding also understudied. The IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report also notes that several factors that increase general conflict risk are sensitive to climate change, but that there is no direct and simple causal association between nature and society.

Even so, several case studies have linked climate change to increased violent conflicts between farmers and herders in Nigeria, Kenya and Sudan, but have found mixed results for Mali and Tanzania. Evidence is also ambiguous and highly contested for high-intensity conflicts such as civil wars. Claims have been put forward that climate change-related droughts, in combination with other factors, had facilitated the civil war in Darfur, the Arab Spring in Egypt, the Syrian civil war, the Islamist insurgency in Nigeria, and the Somali civil war. Yet some studies have suggested that there is very little evidence for several of these causal claims, including for the cases of Darfur, Egypt, Syria, and Ghana.

Recently, researchers have paid increased attention to the impacts of climate change on low-intensity and even non-violent conflicts, such as riots, demonstrations or sit-ins. Even if people do not have the means or motivation to use violence, they can engage in such forms of conflict, for instance in the face of high food prices or water scarcity. Studies indeed show that in vulnerable societies, the anticipated consequences of climate change such as reduced food and water security increase the risk of protests. These conflicts often add to and trigger the escalation of deeper social and political struggles.

According to a report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, intensifying physical effects of climate change "will exacerbate geopolitical flashpoints, particularly after 2030, and key countries and regions will face increasing risks of instability and need for humanitarian assistance.” It names Afghanistan, Myanmar, Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Iraq, Nicaragua, North Korea and Pakistan as likely to face extreme weather episodes that pose threats to energy, food, water and health security: “Diminished energy, food and water security in the 11 countries probably will exacerbate poverty, tribal or ethnic intercommunal tensions and dissatisfaction with governments, increasing the risk of social, economic, and political instability."

Adaptation

Energy

At least since 2010, the U.S. military begun to push aggressively to develop, evaluate and deploy renewable energy to decrease its need to transport fossil fuels. Based on the 2015 annual report from NATO, the alliance plans investments in renewables and energy efficiency to reduce risks to soldiers, and cites the impacts from climate change on security as a reason.

Climate security practices

Due to the growing importance of climate security on the agendas of many governments, international organisations, and other bodies some now run programmes which are designed to mitigate the effects of climate change on conflict. These practices are known as climate security practices which are defined by von Lossow et al. as “tangible actions implemented by a (local or central) government, organisation, community, private actor or individual to help prevent, reduce, mitigate or adapt (to) security risks and threats related to impacts of climate change and related environmental degradation”. The Planetary Security Initiative at the Clingendael Institute maintain an updated list of climate security practices.

These practices stem from a variety of actors with different motivations in the sphere of development, diplomacy and defence. An example is the Arms to Farms project in Kauswagan municipality, the Philippines. An insurgency in the area was aggravated by food insecurity because irregular rainfall that caused poor harvests led to an uptick in insurgent recruitment sparking further violence. The project successfully integrated former insurgents into the community by training them in agricultural methods and fostering trust between communities, increasing food security, peace and human security overall. Another example is a division of the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali (MINUSMA) that seeks to solve community conflicts, which can stem from climate change caused resource shortages. One project in Kidal built a new and more effective water pump in order to solve the issue of conflict between different stakeholders in the area over water which risked a violent confrontation.

The field of climate security practices is still young and even though the issue is growing in importance, some actors are still reluctant to get involved due to the uncertainty inherent in the new field. Because climatic change will only increase in the near future von Lossow et al. conclude that expanding the number of climate security practices in vulnerable areas of the world has “huge potential to catalyse more sustainable and long-term peace and stability”.

Political discourse

The transnational character of climate-related security risks often goes beyond the capacity of national governments to respond adequately. Many parts of governments or state leaders acknowledge climate change as an issue for human security, national or regional security:

United Nations

Although climate change is first and foremost dealt within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and now also under the Paris agreement, the security implications of climate change do not have an institutional home within the United Nations system, and hence remain largely unaddressed, in spite of the urgency of the threat it poses to peace and security in several regions. The UN, through its COP - The Conference of the Parties - is the supreme body to negotiate climate frameworks under the UNFCCC Convention. It consists of the representatives of the Parties to the Convention and holds its sessions every year, and takes decisions which are necessary to ensure the effective implementation of the provisions of the Convention and regularly reviews the implementation of these provisions.Preventing “dangerous” human interference with the climate system is the ultimate aim of the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC is a “Rio Convention”, one of three adopted at the “Rio Earth Summit” in 1992. The UNFCCC entered into force on 21 March 1994. Today, it has near-universal membership. The COP has discussed Climate Security during panels, workshops as session, but not as a programmatic track. The greater focus on this topic by the UN has led to the launch in October 2018 of the inter-agency DPPA-UNDP-UN Environment cooperation called the ‘Climate Security Mechanism’.

United Nations Security Council

The UN Security Council first debated climate security and energy in 2007 and in 2011 issued a presidential statement expressing concern at the possible adverse security effects of climate change. There has been a series of informal Arria-Formula meetings on issues related to climate change. In July 2018, Sweden initiated a debate on Climate and Security in the United Nations Security Council. Climate change grew beyond its categorisation as a hypothetical, existential risk and became an operational concern of relevance to other peace and security practitioners beyond the diplomats in the Security Council.

European Union (EU)

The European Council's conclusions on climate diplomacy state that "Climate change is a decisive global challenge which, if not urgently managed, will put at risk ... peace, stability and security." The Intelligence on European Pensions and Institutional Investment think-tank published a 2018 report with the key point, "Climate change is an existential risk whose elimination must become a corporate objective". In June 2018 European External Action Service (EEAS) High-Level Event hosted an event themed "Climate, Peace and Security: The Time for Action". The EU's comprehensive approach to security would suggest that the EU is well placed to respond to climate-related security risks. However, recent scientific research shows that the European Union has not yet developed a fully coherent policy.

NATO

NATO stated in 2015 that climate change is a significant security threat and that ‘Its bite is already being felt’. In 2021, NATO agreed a Climate Change and Security Action Plan that committed the alliance to 1) analyse the impact of climate change on NATO's strategic environment and NATO's assets, installations, missions and operations 2) incorporate climate change considerations into its work3) contribute to the mitigation of climate change and 4) exchange with partner countries, as well as with international and regional organizations that are active on climate change and security.

United States

In the United States, analysis of climate security and the development of policy ideas for addressing it has been led by the Center for Climate and Security, founded by Francesco Femia and Caitlin Werrell in 2011, which is now an institute of the Council on Strategic Risks.

US intelligence analysts have expressed concern about the "serious security risks" of climate change since the 1980s. In 2007, the Council on Foreign Relations released a report titled, Climate Change and National Security: An Agenda for Action, stating that "Climate change presents a serious threat to the security and prosperity of the United States and other countries." A 2012 report published by the Joint Global Change Research Institute indicated that second and third order impacts of climate change, such as migration and state stability, are of concern for the US defense and intelligence communities. A 2015 report published by the White House found that climate change puts coastal areas at risk, that a changing Arctic poses risks to other parts of the country, risk for infrastructure, and increases demands on military resources. In 2016, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper noted: "Unpredictable instability has become the “new normal,” and this trend will continue for the foreseeable future...Extreme weather, climate change, environmental degradation, rising demand for food and water, poor policy decisions and inadequate infrastructure will magnify this instability."

A 2015 Pentagon report pointed out how climate denial threatens national security. In 2017, the Trump administration removed climate change from its national security strategy. But in January 2019 the Pentagon released a report stating that climate change is a national security threat to USA. In June 2019, in the course of House Select Committee on Intelligence hearings on the national security implications of climate change, the White House blocked the submission of a statement by the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research Office, and the analyst who wrote the statement resigned. The idea of creating a presidential committee on climate security has been proposed. As part of the United States National Defense Authorization Act the U.S. Congress asked the Department of Defense for a report on climate matters. The report was published in 2019, and notes, "The effects of a changing climate are a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense (DoD or the Department) missions, operational plans, and installations."

Australia

A 2018 published report by the Australian Senate noted how "climate change as a current and existential national security risk... defined as one that threatens the premature extinction of Earth-originating intelligent life or the permanent and drastic destruction of its potential for desirable future development."

United Kingdom

In 2014, David Cameron noted that "Climate change is one of the most serious threats facing our world". A 2018 article in UK's The Independent also argued that the U.S.' Trump administration is ‘putting British national security at risk’, according to over 100 climate scientists.

On September 23, 2021, Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon, UK Minister for the United Nations stated that climate change threatened the safety of the country and all people. He also mentioned that the United Kingdom will host the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow on 31 October – 12 November 2021.

Climate security in Africa

Climate change has had devastating effects on the African continent, affecting the poorest communities. It has escalated food insecurity, led to the displacement of populations and exerted extreme pressure on the available water resources. Africa's exposure to climate change is high due to its low adaptive capacity and limited government capabilities, making it the most vulnerable continent. Although the exact connection between climate change and insecurity is quite blurred, evidence suggests that environmental degradation and resource scarcity contribute to violent conflict in some way. This especially happens when ethnic divisions erupt in countries with weak political systems, and low levels of economic development. A 2007 report by the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-Moon points out that, climate change and environmental degradation were partly responsible for the Darfur, Sudan conflict. Between 1967 and 2007, the total rainfall in the area had reduced by 30 percent and the expansion of the Sahara was beyond a mile every year.The ensuing friction between farmers and pastoralists over the reducing grazing land and the few water sources available was at the heart of the Darfur civil war.Of recent, there has been a connection between climate change and the terrorist uprising around the Lake Chad Basin. Climate change has caused rainfall variations and desertification threatening the well-being of people whose lives depend on Lake Chad. Reports suggest that Lake Chad is shrinking at a fast speed, which is creating sharp competition for water. Conflicts arise when communities relocate to places with better water sources, without respecting national borders. Such conditions have also created an ideal environment for the Nigerian Islamist Insurgent group Boko Haram to extend its territory, hence increasing insecurity in the region. In Senegal, the rise in temperatures has led to the migration of the much-sought-after Sardinella fish. Sardinella is known for its high "economic value and food security". Oftentimes conflicts arise when Senegalese fishermen cross to Mauritania searching for fish. Schmidt and Muggah point out that the continued rise in sea level will likely exacerbate conflicts similar to those already seen in the fishing communities of Senegal. A close look at the Sahel region and the Lake Chad Basin gives an insight into the possible conflicts connected to food security and climate change. As Brown, Hammill and McLeman suggest, strengthening the capacity to adapt to climate change can contribute to the resolution of climate-related conflicts.

Examples

Experts have suggested links to climate change in several major conflicts:

- War in Darfur, where sustained drought encouraged conflict between herders and farmers

- Syrian civil war, preceded by the displacement of 1.5 million people due to drought-induced crop and livestock failure But this is disputed by some academics who say that although the severe drought of 2007 – 2008 in north-east Syria was made more likely by climate change, it is very unlikely that this helped to start the Syrian civil war.

- Islamist insurgency in Nigeria, which exploited natural resource shortages to fuel anti-government sentiment

- Somali Civil War, in which droughts and extreme high temperatures have been linked to violence

- Herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria, Mali, South Sudan and other countries in the Sahel region are exacerbated by climate change.

- Northern Mali conflict, in which droughts and extreme high temperatures have been linked to violence

Additionally, paleoclimatologists have determined the connections between war frequencies and population changes which have led to the various cycles in temperatures since the preindustrial era. Securitization is a slow process that builds on an issue resulting from a variety of political actions and choices. A 2016 study finds that "drought can contribute to sustaining conflict, especially for agriculturally dependent groups and politically excluded groups in very poor countries. These results suggest a reciprocal nature–society interaction in which violent conflict and environmental shock constitute a vicious circle, each phenomenon increasing the group’s vulnerability to the other." Different researchers have done several analyses regarding whether or not climate change has been securitized. It's essential to understand securitization because it could lead to the placing of certain policies. The disasters leading to this process include the vast disturbances in certain communities that have become unsafe and have made them more vulnerable to economic, human, and environmental losses. Different cases have been able to prove this problem in many communities.

According to a report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, intensifying physical effects of climate change "will exacerbate geopolitical flashpoints, particularly after 2030, and key countries and regions will face increasing risks of instability and need for humanitarian assistance.” It names Afghanistan, Myanmar, Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Iraq, Nicaragua, North Korea and Pakistan as likely to face extreme weather episodes that pose threats to energy, food, water and health security: “Diminished energy, food and water security in the 11 countries probably will exacerbate poverty, tribal or ethnic intercommunal tensions and dissatisfaction with governments, increasing the risk of social, economic, and political instability."