Medieval medicine in Western Europe was composed of a mixture of pseudoscientific ideas from antiquity. In the Early Middle Ages, following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, standard medical knowledge was based chiefly upon surviving Greek and Roman texts, preserved in monasteries and elsewhere. Medieval medicine is widely misunderstood, thought of as a uniform attitude composed of placing hopes in the church and God to heal all sicknesses, while sickness itself exists as a product of destiny, sin, and astral influences as physical causes. On the other hand, medieval medicine, especially in the second half of the medieval period (c. 1100–1500 AD), became a formal body of theoretical knowledge and was institutionalized in the universities. Medieval medicine attributed illnesses, and disease, not to sinful behaviour, but to natural causes, and sin was connected to illness only in a more general sense of the view that disease manifested in humanity as a result of its fallen state from God. Medieval medicine also recognized that illnesses spread from person to person, that certain lifestyles may cause ill health, and some people have a greater predisposition towards bad health than others.

Influences

Hippocratic medicine

The Western medical tradition often traces its roots directly to the early Greek civilization, much like the foundation of all of Western society. The Greeks certainly laid the foundation for Western medical practice but much more of Western medicine can be traced to the Middle East, Germanic, and Celtic cultures. The Greek medical foundation comes from a collection of writings known today as the Hippocratic Corpus. Remnants of the Hippocratic Corpus survive in modern medicine in forms like the "Hippocratic Oath" as in to "Do No Harm".

The Hippocratic Corpus, popularly attributed to an ancient Greek medical practitioner known as Hippocrates, lays out the basic approach to health care. Greek philosophers viewed the human body as a system that reflects the workings of nature and Hippocrates applied this belief to medicine. The body, as a reflection of natural forces, contained four elemental properties expressed to the Greeks as the four humors. The humors represented fire, air, earth and water through the properties of hot, cold, dry and moist, respectively. Health in the human body relied on keeping these humors in balance within each person.

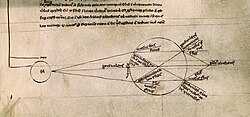

Maintaining the balance of humors within a patient occurred in several ways. An initial examination took place as standard for a physician to properly evaluate the patient. The patient's home climate, their normal diet, and astrological charts were regarded during a consultation. The heavens influenced each person in different ways by influencing elements connected to certain humors, important information in reaching a diagnosis. After the examination, the physician could determine which humor was unbalanced in the patient and prescribe a new diet to restore that balance. Diet included not only food to eat or avoid but also an exercise regimen and medication.

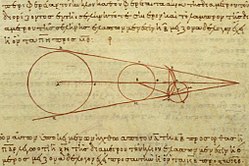

Hippocratic medicine was written down within the Hippocratic Corpus, therefore medical practitioners were required to be literate. The written treatises within the Corpus are varied, incorporating medical doctrine from any source the Greeks came into contact with. At Alexandria in Egypt, the Greeks learned the art of surgery and dissection; the Egyptian skill in these arenas far surpassed those of Greeks and Romans due to social taboos regarding treatment of the dead. The early Hippocratic practitioner Herophilus engaged in dissection and added new knowledge to human anatomy in the realms of the human nervous system, the inner workings of the eye, differentiating arteries from veins, and using pulses as a diagnostic tool in treatment. Surgery and dissection yielded much knowledge of the human body that Hippocratic physicians employed alongside their methods of balancing humors in patients. The combination of knowledge in diet, surgery, and medication formed the foundation of medical learning upon which Galen would later build upon with his own works.

Temple healing

The Greeks had been influenced by their Egyptian neighbours, in terms of medical practice in surgery and medication. However, the Greeks also absorbed many folk healing practices, including incantations and dream healing. In Homer's Iliad and Odyssey the gods are implicated as the cause of plagues or widespread disease and that those maladies could be cured by praying to them. The religious side of Greek medical practice is clearly manifested in the cult of Asclepius, whom Homer regarded as a great physician, and was deified in the third and fourth century BC. Hundreds of temples devoted to Asclepius were founded throughout the Greek and Roman empire to which untold numbers of people flocked for cures. Healing visions and dreams formed the foundation for the curing process as the person seeking treatment from Asclepius slept in a special dormitory. The healing occurred either in the person's dream or advice from the dream could be used to seek out the proper treatment for their illness elsewhere. Afterwards the visitor to the temple bathed, offered prayers and sacrifice, and received other forms of treatment like medication, dietary restrictions, and an exercise regiment, keeping with the Hippocratic tradition.

Pagan and folk medicine

Some of the medicine in the Middle Ages had its roots in pagan and folk practices. This influence was highlighted by the interplay between Christian theologians who adopted aspects of pagan and folk practices and chronicled them in their own works. The practices adopted by Christian medical practitioners around the 2nd century, and their attitudes toward pagan and folk traditions, reflected an understanding of these practices, especially humoralism and herbalism.

The practice of medicine in the early Middle Ages was empirical and pragmatic. It focused mainly on curing disease rather than discovering the cause of diseases. Often it was believed the cause of disease was supernatural. Nevertheless, secular approaches to curing diseases existed. People in the Middle Ages understood medicine by adopting the ancient Greek medical theory of humors. Since it was clear that the fertility of the earth depended on the proper balance of the elements, it followed that the same was true for the body, within which the various humors had to be in balance. This approach greatly influenced medical theory throughout the Middle Ages.

Folk medicine of the Middle Ages dealt with the use of herbal remedies for ailments. The practice of keeping physic gardens teeming with various herbs with medicinal properties was influenced by the gardens of Roman antiquity. Many early medieval manuscripts have been noted for containing practical descriptions for the use of herbal remedies. These texts, such as the Pseudo-Apuleius, included illustrations of various plants that would have been easily identifiable and familiar to Europeans at the time. Monasteries later became centres of medical practice in the Middle Ages, and carried on the tradition of maintaining medicinal gardens. These gardens became specialized and capable of maintaining plants from the Southern Hemisphere as well as maintaining plants during winter.

Hildegard of Bingen was an example of a medieval medical practitioner who, while educated in classical Greek medicine, also utilized folk medicine remedies. Her understanding of the plant based medicines informed her commentary on the humors of the body and the remedies she described in her medical text Causae et curae were influenced by her familiarity with folk treatments of disease. In the rural society of Hildegard's time, much of the medical care was provided by women, along with their other domestic duties. Kitchens were stocked with herbs and other substances required in folk remedies for many ailments. Causae et curae illustrated a view of symbiosis of the body and nature, that the understanding of nature could inform medical treatment of the body. However, Hildegard maintained the belief that the root of disease was a compromised relationship between a person and God. Many parallels between pagan and Christian ideas about disease existed during the early Middle Ages. Christian views of disease differed from those held by pagans because of a fundamental difference in belief: Christians' belief in a personal relationship with God greatly influenced their views on medicine.

Evidence of pagan influence on emerging Christian medical practice was provided by many prominent early Christian thinkers, such as Origen, Clement of Alexandria, and Augustine, who studied natural philosophy and held important aspects of secular Greek philosophy that were in line with Christian thought. They believed faith supported by sound philosophy was superior to simple faith. The classical idea of the physician as a selfless servant who had to endure unpleasant tasks and provide necessary, often painful treatment was of great influence on early Christian practitioners. The metaphor was not lost on Christians who viewed Christ as the ultimate physician. Pagan philosophy had previously held that the pursuit of virtue should not be secondary to bodily concerns. Similarly, Christians felt that, while caring for the body was important, it was second to spiritual pursuits. The relationship between faith and the bodies ailments explains why most medieval medical practice was performed by Christian monks.

Monasteries

Monasteries developed not only as spiritual centers, but also centers of intellectual learning and medical practice. Locations of the monasteries were secluded and designed to be self-sufficient, which required the monastic inhabitants to produce their own food and also care for their sick. Prior to the development of hospitals, people from the surrounding towns looked to the monasteries for help with their sick.

A combination of both spiritual and natural healing was used to treat the sick. Herbal remedies, known as Herbals, along with prayer and other religious rituals were used in treatment by the monks and nuns of the monasteries. Herbs were seen by the monks and nuns as one of God’s creations for the natural aid that contributed to the spiritual healing of the sick individual. An herbal textual tradition also developed in the medieval monasteries. Older herbal Latin texts were translated and also expanded in the monasteries. The monks and nuns reorganized older texts so that they could be utilized more efficiently, adding a table of contents for example to help find information quickly. Not only did they reorganize existing texts, but they also added or eliminated information. New herbs that were discovered to be useful or specific herbs that were known in a particular geographic area were added. Herbs that proved to be ineffective were eliminated. Drawings were also added or modified in order for the reader to effectively identify the herb. The Herbals that were being translated and modified in the monasteries were some of the first medical texts produced and used in medical practice in the Middle Ages.

Not only were herbal texts being produced, but also other medieval texts that discussed the importance of the humors. Monasteries in Medieval Europe gained access to Greek medical works by the middle of the 6th century. Monks translated these works into Latin, after which they were gradually disseminated across Europe. Monks such as Arnald of Villanova also translated the works of Galen and other classical Greek scholars from Arabic to Latin during the Medieval ages. By producing these texts and translating them into Latin, Christian monks both preserved classical Greek medical information and allowed for its use by European medical practitioners. By the early 1300s these translated works would become available at medieval universities and form the foundation of the universities medical teaching programs.

Hildegard of Bingen, a well known abbess, wrote about Hippocratic Medicine using humoral theory and how balance and imbalance of the elements affected the health of an individual, along with other known sicknesses of the time, and ways in which to combine both prayer and herbs to help the individual become well. She discusses different symptoms that were common to see and the known remedies for them.

In exchanging the herbal texts among monasteries, monks became aware of herbs that could be very useful but were not found in the surrounding area. The monastic clergy traded with one another or used commercial means to obtain the foreign herbs. Inside most of the monastery grounds there had been a separate garden designated for the plants that were needed for the treatment of the sick. A serving plan of St. Gall depicts a separate garden to be developed for strictly medical herbals. Monks and nuns also devoted a large amount of their time in the cultivation of the herbs they felt were necessary in the care of the sick. Some plants were not native to the local area and needed special care to be kept alive. The monks used a form of science, what we would today consider botany, to cultivate these plants. Foreign herbs and plants determined to be highly valuable were grown in gardens in close proximity to the monastery in order for the monastic clergy to hastily have access to the natural remedies.

Medicine in the monasteries was concentrated on assisting the individual to return to normal health. Being able to identify symptoms and remedies was the primary focus. In some instances identifying the symptoms led the monastic clergy to have to take into consideration the cause of the illness in order to implement a solution. Research and experimental processes were continuously being implemented in monasteries to be able to successfully fulfill their duties to God to take care of all God's people.

Christian charity

Christian practice and attitudes toward medicine drew on Middle Eastern (particularly from local Jews) and Greek influences. The Jews took their duty to care for their fellow Jews seriously. This duty extended to lodging and medical treatment of pilgrims to the temple at Jerusalem. Temporary medical assistance had been provided in classical Greece for visitors to festivals and the tradition extended through the Roman Empire, especially after Christianity became the state religion prior to the empire's decline. In the early Medieval period, hospitals, poor houses, hostels, and orphanages began to spread from the Middle East, each with the intention of helping those most in need.

Charity, the driving principle behind these healing centers, encouraged the early Christians to care for others. The cities of Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Antioch contained some of the earliest and most complex hospitals, with many beds to house patients and staff physicians with emerging specialties. Some hospitals were large enough to provide education in medicine, surgery and patient care. St. Basil (AD 330–79) argued that God put medicines on the Earth for human use, while many early church fathers agreed that Hippocratic medicine could be used to treat the sick and satisfy the charitable need to help others.

Medicine

Medieval European medicine became more developed during the Renaissance of the 12th century, when many medical texts both on Ancient Greek medicine and on Islamic medicine were translated from Greek and Arabic during the 13th century. The most influential among these texts was Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia written in circa 1030 which summarized the medicine of Greek, Indian and Muslim physicians until that time. The Canon became an authoritative text in European medical education until the early modern period. Other influential texts from Jewish authors include the Liber pantegni by Isaac Israeli ben Solomon, while Arabic authors contributed De Gradibus by Alkindus and Al-Tasrif by Abulcasis.

At Schola Medica Salernitana in Southern Italy, medical texts from Byzantium and the Arab world (see Medicine in medieval Islam) were readily available, translated from the Greek and Arabic at the nearby monastic centre of Monte Cassino. The Salernitan masters gradually established a canon of writings, known as the ars medicinae (art of medicine) or articella (little art), which became the basis of European medical education for several centuries.

During the Crusades the influence of Islamic medicine became stronger. The influence was mutual and Islamic scholars such as Usamah ibn Munqidh also described their positive experience with European medicine – he describes a European doctor successfully treating infected wounds with vinegar and recommends a treatment for scrofula demonstrated to him by an unnamed "Frank".

Classical medicine

Anglo-Saxon translations of classical works like Dioscorides Herbal survive from the 10th century, showing the persistence of elements of classical medical knowledge. Other influential translated medical texts at the time included the Hippocratic Corpus attributed to Hippocrates, and the writings of Galen.

Galen of Pergamon, a Greek, was one of the most influential ancient physicians. Galen described the four classic symptoms of inflammation (redness, pain, heat, and swelling) and added much to the knowledge of infectious disease and pharmacology. His anatomic knowledge of humans was defective because it was based on dissection of animals, mainly apes, sheep, goats and pigs. Some of Galen's teachings held back medical progress. His theory, for example, that the blood carried the pneuma, or life spirit, which gave it its red colour, coupled with the erroneous notion that the blood passed through a porous wall between the ventricles of the heart, delayed the understanding of circulation and did much to discourage research in physiology. His most important work, however, was in the field of the form and function of muscles and the function of the areas of the spinal cord. He also excelled in diagnosis and prognosis.

Medieval surgery

Medieval surgery arose from a foundation created from ancient Egyptian, Greek and Arabic medicine. An example of such influence would be Galen, the most influential practitioner of surgical or anatomical practices that he performed while attending to gladiators at Pergamon. The accomplishments and the advancements in medicine made by the Arabic world were translated and made available to the Latin world. This new wealth of knowledge allowed for a greater interest in surgery.

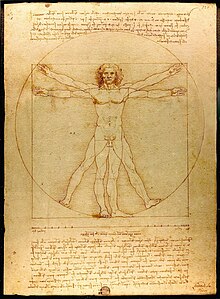

In Paris, in the late thirteenth century, it was deemed that surgical practices were extremely disorganized, and so the Parisian provost decided to enlist six of the most trustworthy and experienced surgeons and have them assess the performance of other surgeons. The emergence of universities allowed for surgery to be a discipline that should be learned and be communicated to others as a uniform practice. The University of Padua was one of the "leading Italian universities in teaching medicine, identification and treating of diseases and ailments, specializing in autopsies and workings of the body." The most prestigious and famous part of the university, the Anatomical Theatre of Padua, is the oldest surviving anatomical theater, in which students studied anatomy by observing their teachers perform public dissections.

Surgery was formally taught in Italy even though it was initially looked down upon as a lower form of medicine. The most important figure of the formal learning of surgery was Guy de Chauliac. He insisted that a proper surgeon should have a specific knowledge of the human body such as anatomy, food and diet of the patient, and other ailments that may have affected the patients. Not only should surgeons have knowledge about the body but they should also be well versed in the liberal arts. In this way, surgery was no longer regarded as a lower practice, but instead began to be respected and gain esteem and status.

During the Crusades, one of the duties of surgeons was to travel around a battlefield, assessing soldiers' wounds and declaring whether or not the soldier was deceased. Because of this task, surgeons were deft at removing arrowheads from their patients' bodies. Another class of surgeons that existed were barber surgeons. They were expected not only to be able to perform formal surgery, but also to be deft at cutting hair and trimming beards. Some of the surgical procedures they would conduct were bloodletting and treating sword and arrow wounds.

In the mid-fourteenth century, there were restrictions placed on London surgeons as to what types of injuries they were able to treat and the types of medications that they could prescribe or use, because surgery was still looked at as an incredibly dangerous procedure that should only be used appropriately. Some of the wounds that were allowed to be performed on were external injuries, such as skin lacerations caused by a sharp edge, such as by a sword, dagger and axe or through household tools such as knives. During this time, it was also expected that the surgeons were extremely knowledgeable on human anatomy and would be held accountable for any consequences as a result of the procedure.

Advances

The Middle Ages contributed a great deal to medical knowledge. This period contained progress in surgery, medical chemistry, dissection, and practical medicine. The Middle Ages laid the ground work for later, more significant discoveries. There was a slow but constant progression in the way that medicine was studied and practiced. It went from apprenticeships to universities and from oral traditions to documenting texts. The most well-known preservers of texts, not only medical, would be the monasteries. The monks were able to copy and revise any medical texts that they were able to obtain.

Besides documentation the Middle Ages also had one of the first well known female physicians, Hildegard of Bingen. Hildegard was born in 1098 and at the age of fourteen she entered the double monastery of Dissibodenberg. She wrote the medical text Causae et curae, in which many medical practices of the time were demonstrated. This book contained diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of many different diseases and illnesses. This text sheds light on medieval medical practices of the time. It also demonstrates the vast amount of knowledge and influences that she built upon. In this time period medicine was taken very seriously, as is shown with Hildegard's detailed descriptions on how to perform medical tasks. The descriptions are nothing without their practical counterpart, and Hildegard was thought to have been an infirmarian in the monastery where she lived. An infirmarian treated not only other monks but pilgrims, workers, and the poor men, women, and children in the monastery's hospice. Because monasteries were located in rural areas the infirmarian was also responsible for the care of lacerations, fractures, dislocations, and burns. Along with typical medical practice the text also hints that the youth (such as Hildegard) would have received hands-on training from the previous infirmarian. Beyond routine nursing this also shows that medical remedies from plants, either grown or gathered, had a significant impact of the future of medicine. This was the beginnings of the domestic pharmacy.

Although plants were the main source of medieval remedies, around the sixteenth century medical chemistry became more prominent. "Medical chemistry began with the adaptation of chemical processes to the preparation of medicine". Previously medical chemistry was characterized by any use of inorganic materials, but it was later refined to be more technical, like the processes of distillation. John of Rupescissa's works in alchemy and the beginnings of medical chemistry is recognized for the bounds in chemistry. His works in making the philosopher's stone, also known as the fifth essence, were what made he became known for. Distillation techniques were mostly used, and it was said that by reaching a substance's purest form the person would find the fifth essence, and this is where medicine comes in. Remedies were able to be made more potent because there was now a way to remove nonessential elements. This opened many doors for medieval physicians as new, different remedies were made. Medical chemistry provided an "increasing body of pharmacological literature dealing with the use of medicines derived from mineral sources". Medical chemistry also shows the use of alcohols in medicine. Though these events were not huge bounds for the field, they were influential in determining the course of science. It was the start of differentiation between alchemy and chemistry.

The Middle Ages brought a new way of thinking and a lessening on the taboo of dissection. Dissection for medical purposes became more prominent around 1299. During this time the Italians were practicing anatomical dissection and the first record of an autopsy dates from 1286. Dissection was first introduced in the educational setting at the university of Bologna, to study and teach anatomy. The fourteenth century saw a significant spread of dissection and autopsy in Italy, and was not only taken up by medical faculties, but by colleges for physicians and surgeons.

Roger Frugardi of Parma composed his treatise on Surgery around about 1180. Between 1250 and 1265 Theodoric Borgognoni produced a systematic four volume treatise on surgery, the Cyrurgia, which promoted important innovations as well as early forms of antiseptic practice in the treatment of injury, and surgical anaesthesia using a mixture of opiates and herbs.

Compendiums like Bald's Leechbook (circa 900), include citations from a variety of classical works alongside local folk remedies.

Theories of medicine

Although each of these theories has distinct roots in different cultural and religious traditions, they were all intertwined in the general understanding and practice of medicine. For example, the Benedictine abbess and healer, Hildegard of Bingen, claimed that black bile and other humour imbalances were directly caused by presence of the Devil and by sin. Another example of the fusion of different medicinal theories is the combination of Christian and pre-Christian ideas about elf-shot (elf- or fairy-caused diseases) and their appropriate treatments. The idea that elves caused disease was a pre-Christian belief that developed into the Christian idea of disease-causing demons or devils. Treatments for this and other types of illness reflected the coexistence of Christian and pre-Christian or pagan ideas of medicine.

Humours

The theory of humours was derived from the ancient medical works and was accepted until the 19th century. The theory stated that within every individual there were four humours, or principal fluids – black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood, these were produced by various organs in the body, and they had to be in balance for a person to remain healthy. Too much phlegm in the body, for example, caused lung problems; and the body tried to cough up the phlegm to restore a balance. The balance of humours in humans could be achieved by diet, medicines, and by blood-letting, using leeches. Leeches were usually starved the day before application to a patient in order to increase their efficiency. The four humours were also associated with the four seasons, black bile-autumn, yellow bile-summer, phlegm-winter and blood-spring.

| HUMOUR | TEMPER | ORGAN | NATURE | ELEMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black bile | Melancholic | Spleen | Cold Dry | Earth |

| Phlegm | Phlegmatic | Lungs | Cold Wet | Water |

| Blood | Sanguine | Head | Warm Wet | Air |

| Yellow bile | Choleric | Gall Bladder | Warm Dry | Fire |

The astrological signs of the zodiac were also thought to be associated with certain humours . Even now, some still use words "choleric", "sanguine", "phlegmatic" and "melancholic" to describe personalities.

Herbalism and botany

Herbs were commonly used in salves and drinks to treat a range of maladies. The particular herbs used depended largely on the local culture and often had roots in pre-Christian religion. The success of herbal remedies was often ascribed to their action upon the humours within the body. The use of herbs also drew upon the medieval Christian doctrine of signatures which stated that God had provided some form of alleviation for every ill, and that these things, be they animal, vegetable or mineral, carried a mark or a signature upon them that gave an indication of their usefulness. For example, skullcap seeds (used as a headache remedy) can appear to look like miniature skulls; and the white spotted leaves of lungwort (used for tuberculosis) bear a similarity to the lungs of a diseased patient. A large number of such resemblances were believed to exist.

Many monasteries developed herb gardens for use in the production of herbal cures, and these remained a part of folk medicine, as well as being used by some professional physicians. Books of herbal remedies were produced, one of the most famous being the Welsh, Red Book of Hergest, dating from around 1400.

During the early Middle Ages, botany had undergone drastic changes from that of its antiquity predecessor (Greek practice). An early medieval treatise in the West on plants known as the Ex herbis femininis was largely based on Dioscorides Greek text: De material medica. The Ex herbis was a lot more popular during this time because it was not only easier to read, but contained plants and their remedies that related to the regions of southern Europe, where botany was being studied. It also provided better medical direction on how to create remedies, and how to properly use them. This book was also highly illustrated, where its former was not, making the practice of botany easier to comprehend.

The re-emergence of Botany in the medieval world came about during the sixteenth century. As part of the revival of classical medicine, one of the biggest areas of interest was materia medica: the study of remedial substances. “Italian humanists in the fifteenth century had recovered and translated ancient Greek botanical texts which had been unknown in the West in the Middle Ages or relatively ignored”. Soon after the rise in interest in botany, universities such as Padua and Bologna started to create programs and fields of study; some of these practices including setting up gardens so that students were able to collect and examine plants. “Botany was also a field in which printing made a tremendous impact, through the development of naturalistic illustrated herbals”. During this time period, university practices were highly concerned with the philosophical matters of study in sciences and the liberal arts, “but by the sixteenth century both scholastic discussion of plants and reliance upon intermediary compendia for plant names and descriptions were increasingly abandoned in favor of direct study of the original texts of classical authors and efforts to reconcile names, descriptions, and plants in nature”. Botanist expanded their knowledge of different plant remedies, seeds, bulbs, uses of dried and living plants through continuous interchange made possible by printing. In sixteenth century medicine, botany was rapidly becoming a lively and fast-moving discipline that held wide universal appeal in the world of doctors, philosophers, and pharmacists.

Mental disorders

Those with mental disorders in medieval Europe were treated using a variety of different methods, depending on the beliefs of the physician they would go to. Some doctors at the time believed that supernatural forces such as witches, demons or possession caused mental disorders. These physicians believed that prayers and incantations, along with exorcisms, would cure the afflicted and relieve them of their suffering. Another form of treatment existed to help expel evil spirits from the body of a patient, known as trephining. Trephining was a means of treating epilepsy by opening a hole in the skull through drilling or cutting. It was believed that any evil spirit or evil air would flow out of the body through the hole and leave the patient in peace. Contrary to the common belief that most physicians in Medieval Europe believed that mental illness was caused by supernatural factors, it is believed that these were only the minority of cases related to the diagnosis and treatment of those suffering from mental disorders. Most physicians believed that these disorders were caused by physical factors, such as the malfunction of organs or an imbalance of the humors. One of the most well-known and reported examples was the belief that an excess amount of black bile was the cause of melancholia, which would now be classified as schizophrenia or depression. Medieval physicians used various forms of treatment to try to fix any physical problems that were causing mental disorders in their patients. When the cause of the disorder being examined was believed to be caused by an imbalance of the four humors, doctors attempted to rebalance the body. They did so through a combination of emetics, laxatives and different methods of bloodletting, in order to remove excess amounts of bodily fluids.

Christian interpretation

Medicine in the Middle Ages was rooted in Christianity through not only the spread of medical texts through monastic tradition but also through the beliefs of sickness in conjunction with medical treatment and theory. Christianity, throughout the medieval period, did not set medical knowledge back or forwards. The church taught that God sometimes sent illness as a punishment, and that in these cases, repentance could lead to a recovery. This led to the practice of penance and pilgrimage as a means of curing illness. In the Middle Ages, some people did not consider medicine a profession suitable for Christians, as disease was often considered God-sent. God was considered to be the "divine physician" who sent illness or healing depending on his will. From a Christian perspective, disease could be seen either as a punishment from God or as an affliction of demons (or elves, see first paragraph under Theories of Medicine). The ultimate healer in this interpretation is of course God, but medical practitioners cited both the bible and Christian history as evidence that humans could and should attempt to cure diseases. For example, the Lorsch Book of Remedies or the Lorsch Leechbook contains a lengthy defense of medical practice from a Christian perspective. Christian treatments focused on the power of prayer and holy words, as well as liturgical practice.

However, many monastic orders, particularly the Benedictines, were very involved in healing and caring for the sick and dying. In many cases, the Greek philosophy that early Medieval medicine was based upon was compatible with Christianity. Though the widespread Christian tradition of sickness being a divine intervention in reaction to sin was popularly believed throughout the Middle Ages, it did not rule out natural causes. For example, the Black Death was thought to have been caused by both divine and natural origins. The plague was thought to have been a punishment from God for sinning, however because it was believed that God was the reason for all natural phenomena, the physical cause of the plague could be scientifically explained as well. One of the more widely accepted scientific explanations of the plague was the corruption of air in which pollutants such as rotting matter or anything that gave the air an unpleasant scent caused the spread of the plague.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) played an important role in how illness was interpreted through both God and natural causes through her medical texts as well. As a nun, she believed in the power of God and prayer to heal, however she also recognized that there were natural forms of healing through the humors as well. Though there were cures for illness outside of prayer, ultimately the patient was in the hands of God. One specific example of this comes from her text Causae et Curae in which she explains the practice of bleeding:

Bleeding, says Hildegard, should be done when the moon is waning, because then the "blood is low" (77:23–25). Men should be bled from the age of twelve (120:32) to eighty (121:9), but women, because they have more of the detrimental humors, up to the age of one hundred (121:24). For therapeutic bleeding, use the veins nearest the diseased part (122:19); for preventive bleeding, use the large veins in the arms (121:35–122:11), because they are like great rivers whose tributaries irrigate the body (123:6–9, 17–20). 24 From a strong man, take "the amount that a thirsty person can swallow in one gulp" (119:20); from a weak one, "the amount that an egg of moderate size can hold" (119:22–23). Afterward, let the patient rest for three days and give him undiluted wine (125:30), because "wine is the blood of the earth" (141:26). This blood can be used for prognosis; for instance, "if the blood comes out turbid like a man's breath, and if there are black spots in it, and if there is a waxy layer around it, then the patient will die, unless God restore him to life" (124:20–24).

Monasteries were also important in the development of hospitals throughout the Middle Ages, where the care of sick members of the community was an important obligation. These monastic hospitals were not only for the monks who lived at the monasteries but also the pilgrims, visitors and surrounding population. The monastic tradition of herbals and botany influenced Medieval medicine as well, not only in their actual medicinal uses but in their textual traditions. Texts on herbal medicine were often copied in monasteries by monks, but there is substantial evidence that these monks were also practicing the texts that they were copying. These texts were progressively modified from one copy to the next, with notes and drawings added into the margins as the monks learned new things and experimented with the remedies and plants that the books supplied. Monastic translations of texts continued to influence medicine as many Greek medical works were translated into Arabic. Once these Arabic texts were available, monasteries in western Europe were able to translate them, which in turn would help shape and redirect Western medicine in the later Middle Ages. The ability for these texts to spread from one monastery or school in adjoining regions created a rapid diffusion of medical texts throughout western Europe.

The influence of Christianity continued into the later periods of the Middle Ages as medical training and practice moved out of the monasteries and into cathedral schools, though more for the purpose of general knowledge rather than training professional physicians. The study of medicine was eventually institutionalized into the medieval universities. Even within the university setting, religion dictated a lot of the medical practice being taught. For instance, the debate of when the spirit left the body influenced the practice of dissection within the university setting. The universities in the south believed that the soul only animated the body and left immediately upon death. Because of this, the body while still important, went from being a subject to an object. However, in the north they believed that it took longer for the soul to leave as it was an integral part of the body. Though medical practice had become a professional and institutionalized field, the argument of the soul in the case of dissection shows that the foundation of religion was still an important part of medical thought in the late Middle Ages.

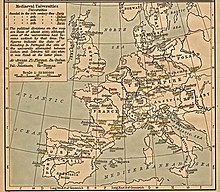

Medical universities in medieval Europe

Medicine was not a formal area of study in early medieval medicine, but it grew in response to the proliferation of translated Greek and Arabic medical texts in the 11th century. Western Europe also experienced economic, population and urban growth in the 12th and 13th centuries leading to the ascent of medieval medical universities. The University of Salerno was considered to be a renowned provenance of medical practitioners in the 9th and 10th centuries, but was not recognized as an official medical university until 1231. The founding of the Universities of Paris (1150), Bologna (1158), Oxford (1167), Montpelier (1181), Padua (1222) and Lleida (1297) extended the initial work of Salerno across Europe, and by the 13th century, medical leadership had passed to these newer institutions. Despite Salerno's important contributions to the foundation of the medical curriculum, scholars do not consider Salerno to be one of the medieval medical universities. This is because the formal establishment of a medical curriculum occurred after the decline of Salerno's grandeur of being a center for academic medicine.

The medieval medical universities' central concept concentrated on the balance between the humors and "in the substances used for therapeutic purposes". The curriculum's secondary concept focused on medical astrology, where celestial events were thought to influence health and disease. The medical curriculum was designed to train practitioners. Teachers of medical students were often successful physicians, practicing in conjunction with teaching. The curriculum of academic medicine was fundamentally based on translated texts and treatises attributed to Hippocrates and Galen as well as Arabic medical texts. At Montpellier's Faculty of Medicine professors were required in 1309 to possess Galen's books which described humors, De complexionibus, De virtutibus naturalibus, De criticis diebu so that they could teach students about Galen's medical theory. The translated works of Hippocrates and Galen were often incomplete, and were mediated with Arabic medical texts for their "independent contributions to treatment and to herbal pharmacology". Although anatomy was taught in academic medicine through the dissection of cadavers, surgery was largely independent from medical universities. The University of Bologna was the only university to grant degrees in surgery. Academic medicine also focused on actual medical practice where students would study individual cases and observe the professor visiting patients.

The required number of years to become a licensed physician varied among universities. Montpellier required students without their masters of arts to complete three and a half years of formal study and six months of outside medical practice. In 1309, the curriculum of Montpellier was changed to six years of study and eight months of outside medical practice for those without a masters of arts, whereas those with a masters of arts were only subjected to five years of study with eight months of outside medical practice. The university of Bologna required three years of philosophy, three years of astrology, and four years of attending medical lectures.

Medical practitioners

Members of religious orders were major sources of medical knowledge and cures. There appears to have been some controversy regarding the appropriateness of medical practice for members of religious orders. The Decree of the Second Lateran Council of 1139 advised the religious to avoid medicine because it was a well-paying job with higher social status than was appropriate for the clergy. However, this official policy was not often enforced in practice and many religious continued to practice medicine.

There were many other medical practitioners besides clergy. Academically trained doctors were particularly important in cities with universities. Medical faculty at universities figured prominently in defining medical guilds and accepted practices as well as the required qualifications for physicians. Beneath these university-educated physicians there existed a whole hierarchy of practitioners. Wallis suggests a social hierarchy with these university educated physicians on top, followed by "learned surgeons; craft-trained surgeons; barber surgeons, who combined bloodletting with the removal of "superfluities" from the skin and head; itinerant specialist such as dentist and oculists; empirics; midwives; clergy who dispensed charitable advice and help; and, finally, ordinary family and neighbors". Each of these groups practiced medicine in their own capacity and contributed to the overall culture of medicine.

Hospital system

In the Medieval period the term hospital encompassed hostels for travellers, dispensaries for poor relief, clinics and surgeries for the injured, and homes for the blind, lame, elderly, and mentally ill. Monastic hospitals developed many treatments, both therapeutic and spiritual.

During the thirteenth century an immense number of hospitals were built. The Italian cities were the leaders of the movement. Milan had no fewer than a dozen hospitals and Florence before the end of the fourteenth century had some thirty hospitals. Some of these were very beautiful buildings. At Milan a portion of the general hospital was designed by Bramante and another part of it by Michelangelo. The Hospital in Sienna, built in honor of St. Catherine, has been famous ever since. Everywhere throughout Europe this hospital movement spread. Virchow, the great German pathologist, in an article on hospitals, showed that every city of Germany of five thousand inhabitants had its hospital. He traced all of this hospital movement to Pope Innocent III, and though he was least papistically inclined, Virchow did not hesitate to give extremely high praise to this pontiff for all that he had accomplished for the benefit of children and suffering mankind.

Hospitals began to appear in great numbers in France and England. Following the French Norman invasion into England, the explosion of French ideals led most Medieval monasteries to develop a hospitium or hospice for pilgrims. This hospitium eventually developed into what we now understand as a hospital, with various monks and lay helpers providing the medical care for sick pilgrims and victims of the numerous plagues and chronic diseases that afflicted Medieval Western Europe. Benjamin Gordon supports the theory that the hospital – as we know it – is a French invention, but that it was originally developed for isolating lepers and plague victims, and only later undergoing modification to serve the pilgrim.

Owing to a well-preserved 12th-century account of the monk Eadmer of the Canterbury cathedral, there is an excellent account of Bishop Lanfranc's aim to establish and maintain examples of these early hospitals:

But I must not conclude my work by omitting what he did for the poor outside the walls of the city Canterbury. In brief, he constructed a decent and ample house of stone…for different needs and conveniences. He divided the main building into two, appointing one part for men oppressed by various kinds of infirmities and the other for women in a bad state of health. He also made arrangements for their clothing and daily food, appointing ministers and guardians to take all measures so that nothing should be lacking for them.

Later developments

High medieval surgeons like Mondino de Liuzzi pioneered anatomy in European universities and conducted systematic human dissections. Unlike pagan Rome, high medieval Europe did not have a complete ban on human dissection. However, Galenic influence was still so prevalent that Mondino and his contemporaries attempted to fit their human findings into Galenic anatomy.

During the period of the Renaissance from the mid 1450s onward, there were many advances in medical practice. The Italian Girolamo Fracastoro (1478–1553) was the first to propose that epidemic diseases might be caused by objects outside the body that could be transmitted by direct or indirect contact. He also proposed new treatments for diseases such as syphilis.

In 1543 the Flemish Scholar Andreas Vesalius wrote the first complete textbook on human anatomy: "De Humani Corporis Fabrica", meaning "On the Fabric of the Human Body". Much later, in 1628, William Harvey explained the circulation of blood through the body in veins and arteries. It was previously thought that blood was the product of food and was absorbed by muscle tissue.

During the 16th century, Paracelsus, like Girolamo, discovered that illness was caused by agents outside the body such as bacteria, not by imbalances within the body.

The French army doctor Ambroise Paré, born in 1510, revived the ancient Greek method of tying off blood vessels. After amputation the common procedure was to cauterize the open end of the amputated appendage to stop the haemorrhaging. This was done by heating oil, water, or metal and touching it to the wound to seal off the blood vessels. Pare also believed in dressing wounds with clean bandages and ointments, including one he made himself composed of eggs, oil of roses, and turpentine. He was the first to design artificial hands and limbs for amputation patients. On one of the artificial hands, the two pairs of fingers could be moved for simple grabbing and releasing tasks and the hand looked perfectly natural underneath a glove.

Medical catastrophes were more common in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance than they are today. During the Renaissance, trade routes were the perfect means of transportation for disease. Eight hundred years after the Plague of Justinian, the bubonic plague returned to Europe. Starting in Asia, the Black Death reached Mediterranean and western Europe in 1348 (possibly from Italian merchants fleeing fighting in Crimea), and killed 25 million Europeans in six years, approximately 1/3 of the total population and up to a 2/3 in the worst-affected urban areas. Before Mongols left besieged Crimean Kaffa the dead or dying bodies of the infected soldiers were loaded onto catapults and launched over Kaffa's walls to infect those inside. This incident was among the earliest known examples of biological warfare and is credited as being the source of the spread of the Black Death into Europe.

The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean from 14th through 17th centuries. Notable later outbreaks include the Italian Plague of 1629–1631, the Great Plague of Seville (1647–1652), the Great Plague of London (1665–1666), the Great Plague of Vienna (1679), the Great Plague of Marseille in 1720–1722 and the 1771 plague in Moscow.

Before the Spanish discovered the New World (continental America), the deadly infections of smallpox, measles, and influenza were unheard of. The Native Americans did not have the immunities the Europeans developed through long contact with the diseases. Christopher Columbus ended the Americas' isolation in 1492 while sailing under the flag of Castile, Spain. Deadly epidemics swept across the Caribbean. Smallpox wiped out villages in a matter of months. The island of Hispaniola had a population of 250,000 Native Americans. 20 years later, the population had dramatically dropped to 6,000. 50 years later, it was estimated that approximately 500 Native Americans were left. Smallpox then spread to the area which is now Mexico where it then helped destroy the Aztec Empire. In the 1st century of Spanish rule in what is now Mexico, 1500–1600, Central and South Americans died by the millions. By 1650, the majority of New Spain (now Mexico) population had perished.

Contrary to popular belief bathing and sanitation were not lost in Europe with the collapse of the Roman Empire. Bathing in fact did not fall out of fashion in Europe until shortly after the Renaissance, replaced by the heavy use of sweat-bathing and perfume, as it was thought in Europe that water could carry disease into the body through the skin. Medieval church authorities believed that public bathing created an environment open to immorality and disease. Roman Catholic Church officials even banned public bathing in an unsuccessful effort to halt syphilis epidemics from sweeping Europe.

Battlefield medicine

Camp and movement

In order for an army to be in good fighting condition, it must maintain the health of its soldiers. One way of doing this is knowing the proper location to set up camp. Military camps were not to be set up in any sort of marshy region. Marsh lands tend to have standing water, which can draw in mosquitos. Mosquitos, in turn, can carry deadly disease, such as malaria. As the camp and troops were needed to be moved, the troops would be wearing heavy soled shoes in order to prevent wear on soldiers' feet. Waterborne illness has also remained an issue throughout the centuries. When soldiers would look for water they would be searching for some sort of natural spring or other forms of flowing water. When water sources were found, any type of rotting wood, or plant material, would be removed before the water was used for drinking. If these features could not be removed, then water would be drawn from a different part of the source. By doing this the soldiers were more likely to be drinking from a safe source of water. Thus, water borne bacteria had less chance of making soldiers ill. One process used to check for dirty water was to moisten a fine white linen cloth with the water and leave it out to dry. If the cloth had any type of stain, it would be considered to be diseased. If the cloth was clean, the water was healthy and drinkable. Freshwater also assists with sewage disposal, as well as wound care. Thus, a source of fresh water was a preemptive measure taken to defeat disease and keep men healthy once they were wounded.

Physicians

Surgeons

In Medieval Europe the surgeon's social status improved greatly as their expertise was needed on the battlefield. Owing to the number of patients, warfare created a unique learning environment for these surgeons. The dead bodies also provided an opportunity for learning. The corpses provided a means to learn through hands on experience. As war declined, the need for surgeons declined as well. This would follow a pattern, where the status of the surgeon would flux in regards to whether or not there was actively a war going on.

First medical schools

Medical school also first appeared in the Medieval period. This created a divide between physicians trained in the classroom and physicians who learned their trade through practice. The divide created a shift leading to physicians trained in the classroom to be of higher esteem and more knowledgeable. Despite this, there was still a lack of knowledge by physicians in the militaries. The knowledge of the militaries' physicians was greatly acquired through first hand experience. In the Medical schools, physicians such as Galen were referenced as the ultimate source of knowledge. Thus, the education in the schools was aimed at proving these ancient physicians were correct. This created issues as Medieval knowledge surpassed the knowledge of these ancient physicians. In the scholastic setting it still became practice to reference ancient physicians or the other information being presented was not taken seriously.

Level of care

The soldiers that received medical attention was most likely from a physician who was not well trained. To add to this, a soldier did not have a good chance of surviving a wound that needed specific, specialized, or knowledgeable treatment. Surgery was oftentimes performed by a surgeon who knew it as a craft. There were a handful of surgeons such as Henry de Mondeville, who were very proficient and were employed by Kings such as King Phillip. However; this was not always enough to save kings’ lives, as King Richard I of England died of wounds at the siege of Chalus in AD 1199 due to an unskilled arrow extraction.

Wound treatment

Arrow extraction

Treating a wound was and remains the most crucial part of any battlefield medicine, as this is what keeps soldiers alive. As remains true on the modern battlefield, hemorrhaging and shock were the number one killers. Thus, the initial control of these two things were of the utmost importance in medieval medicine. Items such as the long bow were used widely throughout the medieval period, thus making arrow extracting a common practice among the armies of Medieval Europe. When extracting an arrow, there were three guidelines that were to be followed. The physicians should first examine the position of the arrow and the degree to which its parts are visible, the possibility of it being poisoned, the location of the wound, and the possibility of contamination with dirt and other debris. The second rule was to extract it delicately and swiftly. The third rule was to stop the flow of blood from the wound.

The arrowheads that were used against troops were typically not barbed or hooked, but were slim and designed to penetrate armor such as chain mail. Although this design may be useful as wounds were smaller, these arrows were more likely to embed in bone making them harder to extract. If the arrow happened to be barbed or hooked it made the removal more challenging. Physicians would then let the wound putrefy, thus making the tissue softer and easier for arrow extraction. After a soldier was wounded he was taken to a field hospital where the wound was assessed and cleaned, then if time permitted the soldier was sent to a camp hospital where his wound was closed for good and allowed to heal.

Blade and knife wounds

Another common injury faced was those caused by blades. If the wound was too advanced for simple stitch and bandage, it would often result in amputation of the limb. Surgeons of the Medieval battlefield had the practice of amputation down to an art. Typically it would have taken less than a minute for a surgeon to remove the damaged limb, and another three to four minutes to stop the bleeding. The surgeon would first place the limb on a block of wood and tie ligatures above and below the site of surgery. Then the soft tissue would be cut through, thus exposing the bone, which was then sawed through. The stump was then bandaged and left to heal. The rates of mortality among amputation patients was around 39%, that number grew to roughly 62% for those patients with a high leg amputation. Ideas of medieval surgery are often construed in modern minds as barbaric, as our view is diluted with our own medical knowledge. Surgery and medical practice in general was at its height of advancement for its time. All procedures were done with the intent to save lives, not to cause extra pain and suffering. The speed of the procedure by the surgeon was an important factor, as the limit of pain and blood loss lead to higher survival rates among these procedures.

Injuries to major arteries that caused mass blood loss were not usually treatable as shown in the evidence of archeological remains. We know this as wounds severe enough to sever major arteries left incisions on the bone which is excavated by archaeologists. Wounds were also taught to be covered to improve healing. Forms of antiseptics were also used in order to stave off infection. To dress wounds all sorts of dressing were used such as grease, absorbent dressings, spider webs, honey, ground shellfish, clay and turpentine. Some of these methods date back to Roman battlefield medicine.

Bone breakage

Sieges were a dangerous place to be, as broken bones became an issue, with soldiers falling while they scaled the wall amongst other methods of breakage. Typically, it was long bones that were fractured. These fractures were manipulated to get the bones back into their correct location. Once they were in their correct location, the wound was immobilized by either a splint or a plaster mold. The plaster mold (an early cast) was made of flour and egg whites and was applied to the injured area. Both of these methods left the bone immobilized and gave it a chance to heal.

![European output of manuscripts 500–1500[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/24/European_Output_of_Manuscripts_500%E2%80%931500.png/120px-European_Output_of_Manuscripts_500%E2%80%931500.png)