Evolution

Quality management is a recent phenomenon but important for an organization. Civilizations that supported the arts and crafts allowed clients to choose goods meeting higher quality standards than normal goods. In societies where arts and crafts were the responsibility of master craftsmen or artists, these masters would lead studios and train and supervise others. However, the importance of craftsmen diminished as mass production and repetitive work practices were instituted. This approach’s aim was to produce large numbers of the same goods. The first proponent in the US for this approach was Eli Whitney, who proposed (interchangeable) parts manufacture for muskets, hence producing the identical components and creating a musket assembly line. The next step forward was promoted by several people including Frederick Winslow Taylor, a mechanical engineer who sought to improve industrial efficiency. He is sometimes called "the father of scientific management." He was one of the intellectual leaders of the Efficiency Movement and part of his approach laid a further foundation for quality management, including aspects like standardization and adopting improved practices. Henry Ford was also important in bringing process and quality management practices into operation in his assembly lines. In Germany, Karl Benz, often called the inventor of the motor car, was pursuing similar assembly and production practices, although real mass production was only properly initiated in Volkswagen after World War II. From this period onwards, North American companies focused predominantly upon production against lower cost with increased efficiency.

Walter A. Shewhart made a major step in the evolution towards quality management by creating a method for quality control for production, using statistical methods, first proposed in 1924. This became the foundation for his ongoing work on statistical quality control. W. Edwards Deming later applied statistical process control methods in the United States during World War II, thereby successfully improving quality in the manufacture of munitions and other strategically important products.

Quality leadership from a national perspective has changed over the past decades. After the second world war, Japan decided to make quality improvement a national imperative as part of rebuilding their economy, and sought the help of Shewhart, Deming and Juran, amongst others. W. Edwards Deming championed Shewhart's ideas in Japan from 1950 onwards. He is probably best known for his management philosophy establishing quality, productivity, and competitive position. He has formulated 14 points of attention for managers, which are a high level abstraction of many of his deep insights. They should be interpreted by learning and understanding the deeper insights. These 14 points include key concepts such as:

- Break down barriers between departments

- Management should learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership

- Supervision should be to help people and machines and gadgets to do a better job

- Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service

- Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement

- Drive out fear, so that everyone may work effectively for the company

In the 1950s and 1960s, Japanese goods were synonymous with cheapness and low quality, but over time their quality initiatives began to be successful, with Japan achieving high levels of quality in products from the 1970s onward. For example, Japanese cars regularly top the J.D. Power customer satisfaction ratings. In the 1980s Deming was asked by Ford Motor Company to start a quality initiative after they realized that they were falling behind Japanese manufacturers. A number of highly successful quality initiatives have been invented by the Japanese (see for example on this pages: Genichi Taguchi, QFD, Toyota Production System). Many of the methods not only provide techniques but also have associated quality culture (i.e. people factors). These methods are now adopted by the same western countries that decades earlier derided Japanese methods.

Customers recognize that quality is an important attribute in products and services. Suppliers recognize that quality can be an important differentiator between their own offerings and those of competitors (quality differentiation is also called the quality gap). In the past two decades this quality gap has been greatly reduced between competitive products and services. This is partly due to the contracting (also called outsourcing) of manufacture to countries like China and India, as well internationalization of trade and competition. These countries, among many others, have raised their own standards of quality in order to meet international standards and customer demands. The ISO 9000 series of standards are probably the best known International standards for quality management.

Some themes have become more significant including quality culture, the importance of knowledge management, and the role of leadership in promoting and achieving high quality. Disciplines like systems thinking are bringing more holistic approaches to quality so that people, process and products are considered together rather than independent factors in quality management.

Government agencies and industrial organizations that regulate products have recognized that quality culture may assist companies that produce those products. A survey of more than 60 multinational companies found that those companies whose employees rated as having a low quality culture had increased costs of $67 million/year for every 5000 employees compared to those rated as having a strong quality culture.

The influence of quality thinking has spread to non-traditional applications outside of walls of manufacturing, extending into service sectors and into areas such as sales, marketing and customer service. Statistical evidence collected in the banking sector shows a strong correlation between quality culture and competitive advantage.

Customer satisfaction has been the backbone of quality management and still is important. However, there is an expansion of the research focus from a sole customer focus towards a stakeholder focus. This is following the development of stakeholder theory. A further development of quality management is the exploration of synergies between quality management and sustainable development.

Principles

The International Standard for Quality management (ISO 9001:2015) adopts a number of management principles, that can be used by top management to guide their organizations towards improved performance.

Customer focus

The primary focus of quality management is to meet customer requirements and to strive to exceed customer expectations.

Rationale

Sustained success is achieved when an organization attracts and retains the confidence of customers and other interested parties on whom it depends. Every aspect of customer interaction provides an opportunity to create more value for the customer. Understanding current and future needs of customers and other interested parties contributes to sustained success of an organization

Leadership

Leaders at all levels establish unity of purpose and direction and create conditions in which people are engaged in achieving the organization’s quality objectives. Leadership has to take up the necessary changes required for quality improvement and encourage a sense of quality throughout organisation.

Rationale

Creation of unity of purpose and direction and engagement of people enable an organization to align its strategies, policies, processes and resources to achieve its objectives

Engagement of people

Competent, empowered and engaged people at all levels throughout the organization are essential to enhance its capability to create and deliver value.

Rationale

To manage an organization effectively and efficiently, it is important to involve all people at all levels and to respect them as individuals. Recognition, empowerment and enhancement of competence facilitate the engagement of people in achieving the organization’s quality objectives.

Process approach

Consistent and predictable results are achieved more effectively and efficiently when activities are understood and managed as interrelated processes that function as a coherent system.

Rationale

The quality management system consists of interrelated processes. Understanding how results are produced by this system enables an organization to optimize the system and its performance.

Improvement

Successful organizations have an ongoing focus on improvement.

Rationale

Improvement is essential for an organization to maintain current levels of performance, to react to changes in its internal and external conditions and to create new opportunities.

Evidence based decision making

Decisions based on the analysis and evaluation of data and information are more likely to produce desired results.

Rationale

Decision making can be a complex process, and it always involves some uncertainty. It often involves multiple types and sources of inputs, as well as their interpretation, which can be subjective. It is important to understand cause-and-effect relationships and potential unintended consequences. Facts, evidence and data analysis lead to greater objectivity and confidence in decision making.

Relationship management

For sustained success, an organization manages its relationships with interested parties, such as suppliers, retailers.

Rationale

Interested parties influence the performance of an organizations and industry. Sustained success is more likely to be achieved when the organization manages relationships with all of its interested parties to optimize their impact on its performance. Relationship management with its supplier and partner networks is of particular importance.

Criticism

The social scientist Bettina Warzecha (2017) describes the central concepts of Quality Management (QM), such as e.g. process orientation, controllability, and zero defects as modern myths. She alleges that zero-error processes and the associated illusion of controllability involve the epistemological problem of self-referentiality. The emphasis on the processes in QM also ignores the artificiality and thus arbitrariness of the difference between structure and process. Above all, the complexity of management cannot be reduced to standardized (mathematical) procedures. According to her, the risks and negative side effects of QM are usually greater than the benefits (see also brand eins, 2010).

Quality improvement and more

There are many methods for quality improvement. These cover product improvement, process improvement and people based improvement. In the following list are methods of quality management and techniques that incorporate and drive quality improvement:

- ISO 9004 — guidelines for performance improvement.

- ISO 9001 - a certified quality management system (QMS) for organisations who want to prove their ability to consistently provide products and services that meet the needs of their customers and other relevant stakeholders.

- ISO 15504-4: 2005 — information technology — process assessment — Part 4: Guidance on use for process improvement and process capability determination.

- QFD — quality function deployment, also known as the house of quality approach.

- Kaizen — 改善, Japanese for change for the better; the common English term is continuous improvement.

- Zero Defect Program — created by NEC Corporation of Japan, based upon statistical process control and one of the inputs for the inventors of Six Sigma.

- Six Sigma — 6σ, Six Sigma combines established methods such as statistical process control, design of experiments and failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) in an overall framework.

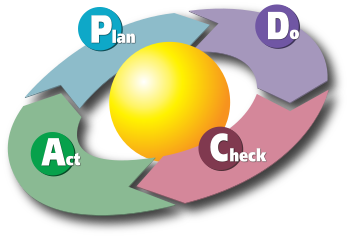

- PDCA — plan, do, check, act cycle for quality control purposes. (Six Sigma's DMAIC method (define, measure, analyze, improve, control) may be viewed as a particular implementation of this.)

- Quality circle — a group (people oriented) approach to improvement.

- Taguchi methods — statistical oriented methods including quality robustness, quality loss function, and target specifications.

- The Toyota Production System — reworked in the west into lean manufacturing.

- Kansei Engineering — an approach that focuses on capturing customer emotional feedback about products to drive improvement.

- TQM — total quality management is a management strategy aimed at embedding awareness of quality in all organizational processes. First promoted in Japan with the Deming prize which was adopted and adapted in USA as the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award and in Europe as the European Foundation for Quality Management award (each with their own variations).

- TRIZ — meaning "theory of inventive problem solving"

- BPR — business process reengineering, a management approach aiming at optimizing the workflows and processes within an organisation.

- OQRM — Object-oriented Quality and Risk Management, a model for quality and risk management.

- Top Down & Bottom Up Approaches—Leadership approaches to change

Proponents of each approach have sought to improve them as well as apply them for small, medium and large gains. Simple one is Process Approach, which forms the basis of ISO 9001:2008 Quality Management System standard, duly driven from the 'Eight principles of Quality management', process approach being one of them. Thareja writes about the mechanism and benefits: "The process (proficiency) may be limited in words, but not in its applicability. While it fulfills the criteria of all-round gains: in terms of the competencies augmented by the participants; the organisation seeks newer directions to the business success, the individual brand image of both the people and the organisation, in turn, goes up. The competencies which were hitherto rated as being smaller, are better recognized and now acclaimed to be more potent and fruitful". The more complex Quality improvement tools are tailored for enterprise types not originally targeted. For example, Six Sigma was designed for manufacturing but has spread to service enterprises. Each of these approaches and methods has met with success but also with failures.

Some of the common differentiators between success and failure include commitment, knowledge and expertise to guide improvement, scope of change/improvement desired (Big Bang type changes tend to fail more often compared to smaller changes) and adaption to enterprise cultures. For example, quality circles do not work well in every enterprise (and are even discouraged by some managers), and relatively few TQM-participating enterprises have won the national quality awards.

There have been well publicized failures of BPR, as well as Six Sigma. Enterprises therefore need to consider carefully which quality improvement methods to adopt, and certainly should not adopt all those listed here.

It is important not to underestimate the people factors, such as culture, in selecting a quality improvement approach. Any improvement (change) takes time to implement, gain acceptance and stabilize as accepted practice. Improvement must allow pauses between implementing new changes so that the change is stabilized and assessed as a real improvement, before the next improvement is made (hence continual improvement, not continuous improvement).

Improvements that change the culture take longer as they have to overcome greater resistance to change. It is easier and often more effective to work within the existing cultural boundaries and make small improvements (that is 'Kaizen') than to make major transformational changes. Use of Kaizen in Japan was a major reason for the creation of Japanese industrial and economic strength.

On the other hand, transformational change works best when an enterprise faces a crisis and needs to make major changes in order to survive. In Japan, the land of Kaizen, Carlos Ghosn led a transformational change at Nissan Motor Company which was in a financial and operational crisis. Well organized quality improvement programs take all these factors into account when selecting the quality improvement methods.

Quality standards

ISO standards

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an independent non-governmental coalition representing 165 countries through their national standards bodies. ISO brings together experts to share knowledge and develop voluntary, consensus-based international commercial, industrial and technical standards.

ISO created Quality Management System (QMS) standards in 1987. They were the ISO 9000:1987 series of standards comprising ISO 9001:1987, ISO 9002:1987 and ISO 9003:1987; which were applicable in different types of industries, based on the type of activity or process: designing, production or service delivery.

The standards are reviewed every few years by the International Organization for Standardization. The version in 1994 was called the ISO 9000:1994 series; consisting of the ISO 9001:1994, 9002:1994 and 9003:1994 versions.

A major revision was published in the year 2000 and the series was called ISO 9000:2000 series. The ISO 9002 and 9003 standards were integrated into one single certifiable standard: ISO 9001:2000. After December 2003, organizations holding ISO 9002 or 9003 standards had to complete a transition to the new standard.

ISO released a minor revision, ISO 9001:2008 on 14 October 2008. It contains no new requirements. Many of the changes were to improve consistency in grammar, facilitating translation of the standard into other languages for use by over 950,000 certified organization in the 175 countries (as at Dec 2007) that use the standard.

The ISO 9004:2009 document gives guidelines for performance improvement over and above the basic standard (ISO 9001:2000). This standard provides a measurement framework for improved quality management, similar to and based upon the measurement framework for process assessment.

The last major revision was published 15 September 2015. This change adopted the High Level Structure, contained in ISO Directive 1 Annex SL, for the first time.

The Quality Management System standards created by ISO are meant for certification of the processes and management arrangements of an organization, not the product or service itself. The ISO 9000 family of standards do not set out requirements for product or service approval. Instead, ISO 9001 requires that product or service requirements are agreed between the organization and its customers, and that the organization manages its business processes to achieve these agreed requirements.

ISO 9001 states that the Quality Management System requirements of the standard are generic and are intended to be applicable to any organization, regardless of its type or size, or the products and services it provides, however, ISO has also published a number of separate standards which specify Quality Management System requirements for specific industries, in many cases those involved in the production or processing of goods typically regulated by nations and other global jurisdictions, in order to ensure that unique elements pertaining to public health and safety are integrated into these Quality Management Systems.

ISO 13485 specifies Quality Management System requirements for organizations involved in the design and manufacture of medical devices in order to demonstrate the ability to meet relevant regulatory requirements. Such organizations can be involved in one or more stages of the life-cycle, including design and development, production, storage and distribution, installation, or servicing of a medical device and design and development or provision of associated activities (e.g. technical support). ISO 13485 can also be used by suppliers or external parties that provide product, including quality management system-related services to such organizations. ISO has not published a standard in similar manner specifying Quality Management System requirements unique to the pharmaceutical industry for regulatory purposes, therefore compliance with ISO 9001 is typically utilized by organizations involved in the design and manufacture of pharmaceuticals.

In 2005 ISO published ISO 22000 specifying the Food Safety Management System requirements for the food industry. This standard covers the values and principles of ISO 9000 and the HACCP standards. It gives one single integrated standard for the food industry, defining requirements for any organization in the food chain.

Technical Standard TS 16949 defines requirements in addition to those in ISO 9001:2008 specifically for the automotive industry.

ISO has a number of standards that support quality management. One group describes processes (including ISO/IEC 12207 and ISO/IEC 15288) and another describes process assessment and improvement ISO 15504.

CMMI and IDEAL methods

The Software Engineering Institute has its own process assessment and improvement methods, called CMMI (Capability Maturity Model Integration) and IDEAL respectively.

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) is a process improvement training and appraisal program and service administered and marketed by Carnegie Mellon University and required by many DOD and U.S. Government contracts, especially in software development. Carnegie Mellon University claims CMMI can be used to guide process improvement across a project, division, or an entire organization. Under the CMMI methodology, processes are rated according to their maturity levels, which are defined as: Initial, Managed, Defined, Quantitatively Managed, Optimizing. Currently supported is CMMI Version 1.3. CMMI is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office by Carnegie Mellon University.

Three constellations of CMMI are:

- Product and service development (CMMI for Development)

- Service establishment, management, and delivery (CMMI for Services)

- Product and service acquisition (CMMI for Acquisition).

CMMI Version 1.3 was released on November 1, 2010. This release is noteworthy because it updates all three CMMI models (CMMI for Development, CMMI for Services, and CMMI for Acquisition) to make them consistent and to improve their high maturity practices. The CMMI Product Team has reviewed more than 1,150 change requests for the models and 850 for the appraisal method.

As part of its mission to transition mature technology to the software community, the SEI has transferred CMMI-related products and activities to the CMMI Institute, a 100%-controlled subsidiary of Carnegie Innovations, Carnegie Mellon University’s technology commercialization enterprise.

Quality management software

Quality Management Software is a category of technologies used by organizations to manage the delivery of high quality products. Solutions range in functionality, however, with the use of automation capabilities they typically have components for managing internal and external risk, compliance, and the quality of processes and products. Pre-configured and industry-specific solutions are available and generally require integration with existing IT architecture applications such as ERP, SCM, CRM, and PLM.

Quality Management Software Functionalities

- Non-Conformances/Corrective and Preventive Action

- Compliance/Audit Management

- Risk Management

- Statistical Process Control

- Failure Mode and Effects Analysis

- Complaint Handling

- Advanced Product Quality Planning

- Environment, Health, and Safety

- Hazard Analysis & Critical Control Points

- Production Part Approval Process

Enterprise Quality Management Software

The intersection of technology and quality management software prompted the emergence of a new software category: Enterprise Quality Management Software (EQMS). EQMS is a platform for cross-functional communication and collaboration that centralizes, standardizes, and streamlines quality management data from across the value chain. The software breaks down functional silos created by traditionally implemented standalone and targeted solutions. Supporting the proliferation and accessibility of information across supply chain activities, design, production, distribution, and service, it provides a holistic viewpoint for managing the quality of products and processes.

Quality terms

- Quality Improvement can be distinguished from Quality Control in that Quality Improvement is the purposeful change of a process to improve the reliability of achieving an outcome.

- Quality Control is the ongoing effort to maintain the integrity of a process to maintain the reliability of achieving an outcome.

- Quality Assurance is the planned or systematic actions necessary to provide enough confidence that a product or service will satisfy the given requirements.