The post-war consensus, sometimes called the post-war compromise, was the economic order and social model of which the major political parties in post-war Britain shared a consensus supporting view, from the end of World War II in 1945 to the late-1970s. It ended during the governance of Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher. The consensus tolerated or encouraged nationalisation, strong trade unions, heavy regulation, high taxes, and an extensive welfare state.

The notion of a post-war consensus covered support for a coherent package of policies that were developed in the 1930s and promised during the Second World War, focused on a mixed economy, Keynesianism, and a broad welfare state. Historians have debated the timing of the weakening and collapse of the consensus, including whether it ended before Thatcherism arrived in 1979. They also suggest that the notion might not have been as widely supported as some claim, and that the word 'consensus' might be inaccurate to describe the period.

Origins of post-war consensus

The thesis of post-war consensus was most fully developed by Paul Addison. The basic argument is that in the 1930s Liberal intellectuals led by John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge developed a series of plans that became especially attractive as the wartime government promised a much better post-war Britain and saw the need to engage every sector of society.

The foundations of the post-war consensus can be traced to the Beveridge Report. This was a report by William Beveridge, a Liberal economist who in 1942 formulated the concept of a more comprehensive welfare state in Great Britain. The report, in shortened terms, aimed to bring widespread reform to the United Kingdom and did so by identifying the "five giants on the road of reconstruction": "Want… Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness". In the report were labelled a number of recommendations: the appointment of a minister to control all the insurance schemes; a standard weekly payment by people in work as a contribution to the insurance fund; old age pensions, maternity grants, funeral grants, pensions for widows and for people injured at work; a new national health service to be established.

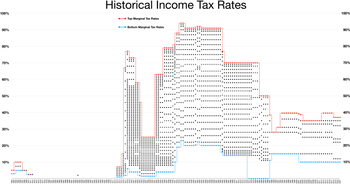

The post-war consensus included a belief in Keynesian economics, a mixed economy with the nationalisation of major industries, the establishment of the National Health Service and the creation of the modern welfare state in Britain. The policies were instituted by all governments (both Labour and Conservative) in the post-war period. The consensus has been held to characterise British politics until the economic crises of the 1970s (see Secondary banking crisis of 1973–1975) which led to the end of the post-war economic boom and the rise of monetarist economics as championed by Milton Friedman. The roots of Keynes's economics, however, stem from critique of the economics of the interwar period depression. Keynes's style of economics encouraged a more active role of the government in order to "manage overall demand so that there was a balance between demand and output". It was claimed that in the period between 1945-1970 (consensus years) that unemployment averaged less than 3%, although the legitimacy of whether this was solely down to Keynes remains unclear.

The first general election since 1935 was held in Britain in July 1945, giving a landslide victory for the Labour Party, whose leader was Clement Attlee. The policies undertaken and implemented by this Labour government laid the base of the consensus. The Conservative Party accepted many of these changes, and promised not to reverse them in its 1947 Industrial Charter. Attlee, using the Beveridge Report and Keynes economics, laid out his plans for what became known as "The Attlee Settlement".

The main areas he would tackle:

- The mixed economy

- Full employment

- Conciliation of the trade unions

- Welfare

- Retreat from empire

Policy areas of consensus

The coalition government during the war, headed by Churchill and Attlee, signed off on a series of white papers that promised Britain a much improved welfare state after the war. The promises included the national health service, and expansion of education, housing, and a number of welfare programmes. It included the nationalisation of weak industries.

In education, the major legislation was the Education Act of 1944, written by Conservative Rab Butler, a moderate, with his deputy, Labour's James Chuter Ede, a former teacher who would become Home Secretary throughout the Attlee administration. It expanded and modernised the educational system and became part of the consensus. The Labour Party did not challenge the system of elite public schools – they became part of the consensus. It also called for building many new universities to dramatically broaden educational base of society. Conservatives did not challenge the socialised medicine of the National Health Service; indeed, they boasted they could do a better job of running it.

In terms of foreign policy, there is much evidence to suggest that there was a shared set of views that were rooted in role of the recent history. Dennis Kavanagh and Peter Morris emphasise the importance of the second world war, and war time cabinet, in yielding a set of values that were shared amongst the major parties rooted in the events leading up to the war: "Atlanticism, the development of an independent nuclear deterrent, the process of imperial disengagement and reluctant Europeanism: all originated in the 1945 Labour Government and were subsequently continued...by its successors". However, there were some disagreement on areas of foreign policy, such as the introduction of the Commonwealth where "Labour opposed the conservative 'imperial rhetoric' with the idealism of multicultural Commonwealth" or, in the same vein, decolonization, which became "an important theme of partisan conflict" in which Conservatives showed a reluctance to give back colonial possessions as well as the gradual process of independence.

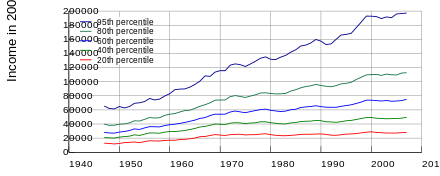

It is argued that from 1945 until the arrival of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, there was a broad multi-partisan national consensus on social and economic policy, especially regarding the welfare state, nationalised health services, educational reform, a mixed economy, government regulation, Keynesian macroeconomic policies, and full employment. Apart from the question of nationalisation of some industries, these policies were broadly accepted by the three major parties, as well as by industry, the financial community and the labour movement. Until the 1980s, historians generally agreed on the existence and importance of the consensus. Some historians such as Ralph Miliband expressed disappointment that the consensus was a modest or even conservative package that blocked a fully socialised society. Historian Angus Calder complained bitterly that the post-war reforms were an inadequate reward for the wartime sacrifices, and a cynical betrayal of the people's hope for a more just post-war society.

However, it is still important to note that there was not total agreement between the two major parties and there were still policies which the Conservatives did not support, such as how the National Health Service would be implemented. Henry Willink, who was the Conservative minister of health from 1943-1945, opposed the nationalisation of hospitals. This could indicate that the post-war consensus may have been exaggerated, as many historians have argued.

Labour revisionism

The Future of Socialism by Anthony Crosland, published in 1956, was one of the most influential books in post-war British Labour Party thinking. It was the seminal work of the 'revisionist' school of Labour politics. A central argument in the book is Crosland's distinction between 'means' and 'ends'. Crosland demonstrates the variety of socialist thought over time, and argues that a definition of socialism founded on nationalisation and public ownership is mistaken, since these are simply one possible means to an end. For Crosland, the defining goal of the left should be more social equality. Crosland also argued that an attack on unjustified inequalities would give any left party a political project to make the definition of the end point of 'how much equality' a secondary and more academic question.

Crosland also developed his argument about the nature of capitalism (developing the argument in his contribution 'The Transition from Capitalism' in the 1952 New Fabian Essays volume). Asking, "is this still capitalism?", Crosland argued that post-war capitalism had fundamentally changed, meaning that the Marxist claim that it was not possible to pursue equality in a capitalist economy was no longer true. Crosland wrote that:

The most characteristic features of capitalism have disappeared – the absolute rule of private property, the subjection of all life to market influences, the domination of the profit motive, the neutrality of government, typical laissez-faire division of income and the ideology of individual rights.

Crosland argued that these features of a reformed managerial capitalism were irreversible. Others within the Labour Party argued that Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan brought about its reversal.

A third important argument was Crosland's liberal vision of the 'good society'. Here his target was the dominance in Labour and Fabian thinking of Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb, and a rather grey, top down bureaucratic vision of the socialist project.

Butskellism

"Butskellism" was a somewhat satirical term sometimes used in British politics to refer to this consensus, established in the 1950s and associated with the exercise of office as Chancellor of the Exchequer by Rab Butler of the Conservatives and Hugh Gaitskell of Labour. The term was inspired by a leading article in The Economist by Norman Macrae which dramatised the claimed convergence by referring to a fictitious "Mr. Butskell".

Debate about consensus

There is much discussion over the extent to which there was actually a consensus, and it has also been challenged as a myth. Many political thinkers and historians have argued both for and against the concept of consensus. Paul Addison, the historian most credited with developing the thesis, has engaged in discussions on the subject with figures such as Kevin Jeffreys, who disagrees. Jeffreys says that "Much of Labour's programme after 1945, it must be remembered, was fiercely contested at the time" using the example of the Conservatives to vote against the NHS. He attributes to the War the reason for the 'shock' result of the 1945 general election. Addison addresses many of Jeffreys' claims, such as the argument that if the Conservatives could have capitalised upon the Beveridge report they would have been the ones with a powerful mandate for pursuing policy, not the Labour party. Addison also changes his stance in this article, stating how he "exaggerated the extent to which 'middle opinion' already prevailed on the front benches" and determining that, in fact he "agree(s) with much of Dr Jeffreys' analysis".

There are also a number of other interpretations of the consensus which many historians have discussed such as Labour Historian Ben Pimlott. He says this idea is a "mirage, an illusion which rapidly fades the closer one gets to it." Pimlott sees much disputation and little harmony. He notes the term "Butskellism" meant harmony of economic policy between the parties, but it was in practice a term of abuse, not celebration. In 2002, Scott Kelly claimed that there was in fact a sustained argument over the use of physical controls, monetary policy and direct taxation. Political scientists Dennis Kavanagh and Peter Morris defend the concept, arguing that clear, major continuities existed regarding policies toward the economy, full employment, trade unions, and welfare programs. There was agreement as well on the major issues of foreign policy.

Dean Blackburn offers a different argument about the accuracy of the consensus. He proffers that the so-called consensus did not stem from ideological agreement, rather, an epistemological one (if any). He makes clear the ideological differences between the Conservatives and the Labour Party; the latter openly wanting an equal and egalitarian society, while the former was more reluctant, for example. Rather, he suggests that an examination of parties' shared epistemological beliefs – "similar ideas about appropriate political conduct", a "shared a common suspicion of the notion that politics could serve fixed 'ends', and...believed that evolutionary change was preferable to radical change" – would offer a better insight into whether or not there was a consensus or not. Blackburn summarises this saying that instead of "being rooted in common ideological beliefs about the desirable 'ends' of political activity, the consensus may have stemmed from epistemological assumptions and the political propositions that followed from them".

Collapse of consensus

Market-orientated conservatives gathered strength in the 1970s in the face of economic paralysis. They rediscovered Friedrich Hayek's The Road to Serfdom (1944) and brought in Milton Friedman, the leader of the Chicago school of economics as Monetarism began to discredit Keynesianism. Keith Joseph played a major role as an advisor to Thatcher.

Keynesianism itself seemed no longer to be the magic bullet for economic crises of the 1970s. Mark Kesselman et al. argue:

Britain was suffering economically without growth and with growing political discontent ... the "winter of discontent" destroyed Britain's collectivist consensus and discredited the Keynesian welfare state.

In 1972, Chancellor of the Exchequer Anthony Barber introduced a tax-cutting budget. A brief "Barber Boom" followed but ended in stagflation and (effectively) devaluation of sterling. Global events such as the 1973 oil crisis put pressure on the post-war consensus; this pressure was intensified by domestic problems such as high inflation, the three-day week and industrial unrest (particularly in the declining coal-mining industry). In early 1976, expectations that inflation and the double deficit would get worse precipitated a sterling crisis. By October, the pound had fallen by almost 25% against the dollar. At this point the Bank of England had exhausted its foreign reserves trying to prop up the currency, and as a result the Callaghan government felt forced to ask the International Monetary Fund for a £2.3 billion loan, then the largest that the IMF had ever made. In return the IMF demanded massive spending cuts and a tightening of the money supply. That marked a suspension of Keynesian economics in Britain. Callaghan reinforced this message in his speech to the Labour Party Conference at the height of the crisis, saying:

We used to think that you could spend your way out of a recession and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting government spending. I tell you in all candour that that option no longer exists, and in so far as it ever did exist, it only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step.

A cause of the supposed collapse of the post war consensus is the idea of the state overload thesis, chiefly examined in the UK by political scientist Anthony King. He summarises the chain of events as saying "Once upon a time, then, man looked to God to order the World. Then he looked to the market. Now he looks to government". It is suggested that due to the increased demand on the government during the consensus years, that an imbalance grew between what was possible to deliver and the demands that had been created. The process is defined as being cyclical: "more demands means more government intervention, which generates yet more expectations". It is believed that these qualms with the consensus are what led, in part, to the emergence of the New Right and Margaret Thatcher.

Thatcher reversed other elements of the post-war consensus, as when her Housing Act 1980 allowed the residents to buy their flats. Thatcher did keep key elements of the post-war consensus, such as nationalised health care. She promised Britons in 1982 that the National Health Service is "safe in our hands."

Economists Stephen Broadberry and Nicholas Crafts have argued that anticompetitive practices, enshrined in the post-war consensus, appear to have hindered the efficient working of the economy and, by implication, the reallocation of resources to their most profitable uses. David Higgins says the statistical data support Broadberry and Crafts.

The consensus was increasingly seen by those on the right as being the cause of Britain's relative economic decline. Believers in New Right political beliefs saw their ideology as the solution to Britain's economic dilemmas in the 1970s. When the Conservative Party won the 1979 general election in the wake of the 1978–79 Winter of Discontent, they implemented New Right ideas and brought the post-war consensus to an end.

New Zealand

Outside Britain, the term "post-war consensus" is used for an era of New Zealand political history, from the first New Zealand Labour Party government of the 1930s until the election of a fundamentally changed Labour party in 1984, following years of mostly New Zealand National Party rule. As in the UK, it was built around a 'historic compromise' between the different classes in society: the rights, health and security of employment for all workers would be promised by government, in return for co-operation between unions and employers. The key ideological tenets of governments of the period were Keynesian economic policy, heavy interventionism, economic regulation and an extensive welfare state.