From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The five-year plans for the development of the national economy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (Russian: Пятилетние планы развития народного хозяйства СССР, Pyatiletniye plany razvitiya narodnogo khozyaystva SSSR) consisted of a series of nationwide centralized economic plans in the Soviet Union, beginning in the late 1920s. The Soviet state planning committee Gosplan developed these plans based on the theory of the productive forces that formed part of the ideology of the Communist Party for development of the Soviet economy. Fulfilling the current plan became the watchword of Soviet bureaucracy.

Several Soviet five-year plans did not take up the full period of

time assigned to them: some were pronounced successfully completed

earlier than expected, some took much longer than expected, and others

failed altogether and had to be abandoned. Altogether, Gosplan launched

thirteen five-year plans. The initial five-year plans aimed to achieve

rapid industrialization in the Soviet Union and thus placed a major focus on heavy industry. The first five-year plan,

accepted in 1928 for the period from 1929 to 1933, finished one year

early. The last five-year plan, for the period from 1991 to 1995, was

not completed, since the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991.

Other communist states, including the People's Republic of China, and to a lesser extent, the Republic of Indonesia, implemented a process of using five-year plans as focal points for economic and societal development.

Background

Joseph Stalin inherited and upheld the New Economic Policy (NEP) from Vladimir Lenin. In 1921, Lenin had persuaded the 10th Party Congress to approve the NEP as a replacement for the War Communism that had been set up during the Russian Civil War. All land had been declared nationalized by the Decree on Land, finalized in the 1922 Land Code, which also set collectivization

as the long-term goal. Although the peasants had been allowed to work

the land they held, the production surplus was bought by the state (on

the state's terms), and the peasants cut production; whereupon food was

requisitioned. Money gradually came to be replaced by barter and a system of coupons.

When the war ended, the NEP took over from War Communism. During

this time, the state had controlled all large enterprises (i.e.

factories, mines, railways) as well as enterprises of medium size, but

small private enterprises,

employing fewer than 20 people, were allowed. The requisitioning of

farm produce was replaced by a tax system (a fixed proportion of the

crop), and the peasants were free to sell their surplus (at a

state-regulated price) - although they were encouraged to join state

farms (Sovkhozes, set up on land expropriated from nobles after the 1917 revolution),

in which they worked for a fixed wage like workers in a factory. The

money came back into use, with new banknotes being issued and backed by

gold.

The NEP had been Lenin's response to a crisis. In 1920,

industrial production had been 13% and agricultural production 20% of

the 1913 figures. Between February 21 and March 17, 1921, the sailors in

Kronstadt had mutinied.

In addition, the Russian Civil War, which had been the main reason for

the introduction of War Communism, had virtually been won; so controls

could be relaxed.

In the 1920s, there was a great debate between Bukharin, Tomsky and Rykov on the one hand, and Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev on the other.

The former group considered that the NEP provided sufficient state

control of the economy and sufficiently rapid development, while the

latter argued in favor of more rapid development and greater state

control, taking the view, among other things, that profits should be

shared among all people, and not just among a privileged few. In 1925,

at the 14th Party Congress,

Stalin, as he usually did in the early days, stayed in the background

but sided with the Bukharin group. However, later, in 1927, he changed

sides, supporting those in favor of a new course, with greater state control.

Plans

Statement from the Newspaper

Pereslavl Week. The text reads:

"Plan is law, fulfillment is duty, over-fulfillment is honor!". Here "duty" can also be interpreted as "obligation."

Each five-year plan dealt with all aspects of development: capital

goods (those used to produce other goods, like factories and machinery),

consumer goods (e.g. chairs, carpets, and irons), agriculture,

transportation, communications, health, education, and welfare. However,

the emphasis varied from plan to plan, although generally, the emphasis

was on power (electricity), capital goods, and agriculture. There were

base and optimum targets. Efforts were made, especially in the third

plan, to move industry eastward to make it safer from attack during World War II.

Soviet planners declared a need for "constant struggle, struggle, and

struggle" to achieve a Communist society. These five-year plans outlined

programs for huge increases in the output of industrial goods. Stalin

warned that without an end to economic backwardness "the advanced

countries...will crush us."

First plan, 1928–1932

Large notice board with slogans about the 5-Year Plan in Moscow, Soviet Union (c., 1931) by a traveler

DeCou, Branson [cs]. It reads like it's made by a state-run paper «Economics and Life» (

Russian:

Экономика и жизнь)

From 1928 to 1940, the number of Soviet workers in industry,

construction, and transport grew from 4.6 million to 12.6 million and

factory output soared. Stalin's first five-year plan helped make the USSR a leading industrial nation.

During this period, the first purges were initiated targeting many people working for Gosplan. These included Vladimir Bazarov, the 1931 Menshevik Trial (centered on Vladimir Groman).

Stalin announced the start of the first five-year plan for

industrialization on October 1, 1928, and it lasted until December 31,

1932. Stalin described it as a new revolution from above.

When this plan began, the USSR was fifth in industrialization, and with

the first five-year plan moved up to second, with only the United

States in first.

This plan met industrial targets in less time than originally

predicted. The production goals were increased by a reported 50% during

the initial deliberation of industrial targets.

Much of the emphasis was placed on heavy industry. Approximately 86% of

all industrial investments during this time went directly to heavy

industry. Officially, the first five-year plan for the industry was

fulfilled to the extent of 93.7% in just four years and three months.

The means of production in regards to heavy industry exceeded the

quota, registering 103.4%. The light, or consumer goods, the industry

reached up to 84.9% of its assigned quota.

However, there is some speculation regarding the legitimacy of these

numbers as the nature of Soviet statistics is notoriously misleading or

exaggerated.

Another issue was that quality was sacrificed in order to achieve

quantity, and production results generated wildly varied items.

Consequently, rationing was implemented to solve chronic food and supply

shortages.

Propaganda

used before, during, and after the first five-year plan compared the

industry to battle. This was highly successful. They used terms such as

"fronts," "campaigns," and "breakthroughs," while at the same time,

workers were forced to work harder than ever before and were organized

into "shock troops," and those who rebelled or failed to keep up with

their work were treated as traitors.

The posters and flyers used to promote and advertise the plan were also

reminiscent of wartime propaganda. A popular military metaphor emerged

from the economic success of the first five-year plan: "There are no

fortresses Bolsheviks cannot storm." Stalin especially liked this.

The first five-year plan was not just about economics. This plan

was a revolution that intended to transform all aspects of society. The

way of life for the majority of the people changed drastically during

this revolutionary time. The plan was also referred to as the "Great Turn".

Individual peasant farming gave way to a more efficient system of

collective farming. Peasant property and entire villages were

incorporated into the state economy which had its own market forces.

There was, however, strong resistance to this at first. The

peasants led an all-out attack to protect individual farming; however,

Stalin rightly did not see the peasants as a threat. Despite being the

largest segment of the population they had no real strength and thus

could pose no serious threat to the state. By the time this was done,

the collectivization plan resembled a very bloody military campaign

against the peasant's traditional lifestyle.

This social transformation along with the incredible economic boom

occurred at the same time that the entire Soviet system developed its

definitive form in the decade of 1930.

Many scholars believe that a few other important factors, such as foreign policy

and internal security, went into the execution of the five-year plan.

While ideology and economics were a major part, preparation for the

upcoming war also affected all of the major parts of the five-year plan.

The war effort really picked up in 1933 when Hitler

came to power in Germany. The stress this caused on internal security

and control in the five-year plan is difficult to document.

While most of the figures were overstated, Stalin was able to

announce truthfully that the plan had been achieved ahead of schedule;

however, the many investments made to the west were excluded. While many

factories were built and industrial production did increase

exponentially, they were not close to reaching their target numbers.

While there was a great success, there were also many problems

with not just the plan itself, but how quickly it was completed. Its

approach to industrialization

was very inefficient and extreme amounts of resources were put into

construction that, in many cases, was never completed. These resources

were also put into equipment that was never used, or not even needed in

the first place. Many of the consumer goods produced during this time were of such low quality that they could never be used and were wasted.

A major event during the first Five Year Plan was the famine of 1932–33.

The famine peaked during the winter of '32–'33 claiming the lives of an

estimated 3.3 to 7 million people, while millions more were

permanently disabled. The famine was the direct result of the industrialization and collectivization implemented by the first Five-Year-Plan.

Many of the peasants who were suffering from the famine began to

sabotage the fulfillment of their obligations to the state and would, as

often as they could, stash away stores of food. Although Stalin was

aware of this, he placed the blame for the hostility onto the peasants,

saying that they had declared war against the Soviet government.

Second plan, 1932–1937

Because of the success made by the first plan, Stalin did not

hesitate with going ahead with the second five-year plan in 1932,

although the official start date for the plan was 1933. The second

five-year plan gave heavy industry top priority, putting the Soviet

Union not far behind Germany

as one of the major steel-producing countries of the world. Further

improvements were made in communications, especially railways, which

became faster and more reliable. As was the case with the other

five-year plans, the second was not as successful, failing to reach the

recommended production levels in such areas as the coal and oil

industries. The second plan employed incentives as well as punishments

and the targets were eased as a reward for the first plan being finished

ahead of schedule in only four years. With the introduction of

childcare, mothers were encouraged to work to aid in the plan's success.

By 1937 the tolkachi emerged occupying a key position mediating between the enterprises and the commissariat.

Consistent with the Soviet doctrine of state atheism (gosateizm), this five-year plan from 1932 to 1937 also included the liquidation of houses of worship, with the goals of closing churches between 1932–1933 and the elimination of clergy by 1935–1936.

Third plan, 1938–1941

The third five-year plan ran for only 3½ years, up to June 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union during the Second World War.

As war approached, more resources were put into developing armaments,

tanks, and weapons, as well as constructing additional military

factories east of the Ural mountains.

The first two years of the third five-year plan proved to be even

more of a disappointment in terms of proclaimed production goals.

Still, a reported 12% to 13% rate of annual industrial growth was

attained in the Soviet Union during the 1930s.

The plan had intended to focus on consumer goods. The Soviet Union

mainly contributed resources to the development of weapons and

constructed additional military factories as needed. By 1952, industrial

production was nearly double the 1941 level ("five-year plans").

Stalin's five-year plans helped transform the Soviet Union from an

untrained society of peasants to an advanced industrial economy.

Fourth and fifth plans, 1945–1955

Stalin in 1945 promised that the USSR would be the leading industrial power by 1960.

The USSR at this stage had been devastated by the war.

Officially, 98,000 collective farms had been ransacked and ruined, with

the loss of 137,000 tractors, 49,000 combine harvesters, 7 million

horses, 17 million cattle, 20 million pigs, 27 million sheep; 25% of

all capital equipment had been destroyed in 35,000 plants and factories;

6 million buildings, including 40,000 hospitals, in 70,666 villages

and 4,710 towns (40% urban housing) were destroyed, leaving 25 million

homeless; about 40% of railway tracks had been destroyed; officially

7.5 million servicemen died, plus 6 million civilians, but perhaps 20

million in all died.

In 1945, mining and metallurgy were at 40% of the 1940 levels, electric

power was down to 52%, pig-iron 26% and steel 45%; food production was

60% of the 1940 level. After Poland, the USSR had been the hardest hit

by the war. Reconstruction was impeded by a chronic labor shortage due

to the enormous number of Soviet casualties in the war (between 20 and

30 million). Moreover, 1946 was the driest year since 1891, and the

harvest was poor.

The USA and USSR were unable to agree on the terms of a US loan

to aid reconstruction, and this was a contributing factor in the rapid

escalation of the Cold War.

However, the USSR did gain reparations from Germany and made Eastern

European countries make payments in return for the Soviets having

liberated them from the Nazis. In 1949, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) was set up, linking the Eastern bloc

countries economically. One-third of the fourth plan's capital

expenditure was spent on Ukraine, which was important agriculturally and

industrially, and which had been one of the areas most devastated by

war.

Sixth plan, 1956–1958

The sixth five-year plan was launched in 1956 during a period of dual leadership under Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin, but it was abandoned after two years due to over-optimistic targets.

Seventh plan, 1959–1965

Grain to increase from 8.5

milliard poods (139 million

tonnes) in 1958 to 10–11 milliard poods (~172 million tonnes) by 1965

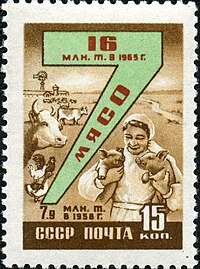

Meat to increase from 7.9 million tonnes in 1958 to 16 million tonnes by 1965

The seven-year plan marked by 1959 postage stamps

Unlike other planning periods, 1959 saw the announcement of a seven-year plan (Russian: семилетка, semiletka), approved by the 21st Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

in 1959. This was merged into a seventh five-year plan in 1961, which

was launched with the slogan "catch up and overtake the USA by 1970."

The plan saw a slight shift away from heavy industry into chemicals,

consumer goods, and natural resources.

The plan also intended to establish 18 new institutes by working with the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences.

Eighth plan, 1966–1970

The eighth plan led to the amount of grain exported being doubled.

Ninth plan, 1971–1975

About 14.5 million tonnes

of grain were imported by the USSR. Détente and improving relations

between the Soviet Union and the United States allowed for more trade.

The plan's focus was primarily on increasing the number of consumer

goods in the economy so as to improve Soviet standards of living. While

largely failing at that objective it managed to significantly improve Soviet computer technology.

Tenth plan, 1976–1980

Leonid Brezhnev declared the slogan "Plan of quality and efficiency" for this period.

Eleventh plan, 1981–1985

During the eleventh five-year plan, the country imported some 42 million tons of grain

annually, almost twice as much as during the tenth five-year plan and

three times as much as during the ninth five-year plan (1971–1975). The

bulk of this grain was sold by the West; in 1985, for example, 94% of

Soviet grain imports were from the non-socialist world, with the United States

selling 14.1 million tons. However, total Soviet export to the West

was always almost as high as the import: for example, in 1984 total

export to the West was 21.3 billion rubles, while total import was 19.6 billion rubles.

Twelfth plan, 1986–1990

The last, 12th plan started with the slogan of uskoreniye (acceleration), the acceleration of economic development (quickly forgotten in favor of a vaguer motto perestroika) ended in a profound economic crisis in virtually all areas of the Soviet economy and a drop in production.

The 1987 Law on State Enterprise and the follow-up decrees about khozraschyot and self-financing in various areas of the Soviet economy were aimed at the decentralization to overcome the problems of the command economy.

Five-year plans in other countries

Most other communist states, including the People's Republic of China, adopted a similar method of planning. Although the Republic of Indonesia under Suharto is known for its anti-communist purge,

his government also adopted the same method of planning because of the

policy of its socialist predecessor, Sukarno. This series of five-year

plans in Indonesia was termed REPELITA (Rencana Pembangunan Lima Tahun); plans I to VI ran from 1969 to 1998.

Information technology

State planning of the economy required processing large amounts of statistical data. The Soviet State had nationalized the Odhner arithmometer

factory in Saint Petersburg after the revolution. The state began

renting tabulating equipment later on. By 1929, it was a very large user

of statistical machines, on the scale of the US or Germany.

The State Bank had tabulating machines in 14 branches. Other users

included the Central Statistical Bureau, the Soviet Commissariat of

Finance, Soviet Commissariat of Inspection, Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Trade, the Grain Trust, Soviet Railways, Russian Ford, Russian Buick, the Karkov tractor factory, and the Tula Armament Works. IBM

also did a good deal of business with the Soviet State in the 1930s,

including supplying punch cards to the Stalin Automobile Plant.

Honors

The minor planet 2122 Pyatiletka discovered in 1971 by Soviet astronomer Tamara Mikhailovna Smirnova is named in honor of five-year plans of the USSR.