From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caste A caste is a fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to: marry exclusively within the same caste (endogamy),

follow lifestyles often linked to a particular occupation, hold a

ritual status observed within a hierarchy, and interact with others

based on cultural notions of exclusion, with certain castes considered as either more pure or more polluted than others. Its paradigmatic ethnographic example is the division of India's Hindu society into rigid social groups, with roots in south Asia's ancient history and persisting to the present time. However, the economic significance of the caste system in India

has been declining as a result of urbanisation and affirmative action

programs. A subject of much scholarship by sociologists and

anthropologists, the Hindu caste system is sometimes used as an

analogical basis for the study of caste-like social divisions existing

outside Hinduism and India. The term "caste" is also applied to

morphological groupings in eusocial insects such as ants, bees, and termites.

Etymology

The English word caste () derives from the Spanish and Portuguese casta, which, according to the John Minsheu's Spanish dictionary (1569), means "race, lineage, tribe or breed". When the Spanish colonised the New World, they used the word to mean a 'clan or lineage'. It was, however, the Portuguese who first employed casta

in the primary modern sense of the English word 'caste' when they

applied it to the thousands of endogamous, hereditary Indian social

groups they encountered upon their arrival in India in 1498. The use of the spelling caste, with this latter meaning, is first attested in English in 1613. In the Latin American context, the term caste is sometimes used to describe the casta

system of racial classification, based on whether a person was of pure

European, Indigenous or African descent, or some mix thereof, with the

different groups being placed in a racial hierarchy; however, despite

the etymological connection between the Latin American casta

system and South Asian caste systems (the former giving its name to the

later), it is controversial to what extent the two phenomenon are really

comparable.

In South Asia

India

Modern India's caste system is based on the artificial modern

superimposition of an old four-fold theoretical classification called

the Varna on the natural social groupings called the Jāti.

Varna conceptualised a society as consisting of four types of varnas, or categories: Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra,

according to the nature of the work of its members. Varna was not an

inherited category and the occupation determined the varna. However, a

person's Jati

is determined at birth and makes them take up that Jati's occupation;

members could and did change their occupation based on personal

strengths as well as economic, social and political factors. Thus, both Jati and Varna were fluid categories, subject to change based on occupation. A 2016 study based on the DNA analysis of unrelated Indians determined that endogamous Jatis originated during the Gupta Empire.

From 1901 onwards, for the purposes of the Decennial Census, the British colonial authorities arbitrarily and incorrectly forced all Jātis into the four Varna categories as described in ancient texts. Herbert Hope Risley,

the Census Commissioner, noted that "The principle suggested as a basis

was that of classification by social precedence as recognized by native

public opinion at the present day, and manifesting itself in the facts

that particular castes are supposed to be the modern representatives of

one or other of the castes of the theoretical Indian system."

Varna, as mentioned in ancient Hindu texts, describes society as divided into four categories: Brahmins (scholars and yajna priests), Kshatriyas (rulers and warriors), Vaishyas (farmers, merchants and artisans) and Shudras (workmen/service providers). The texts do not mention any hierarchy or a separate, untouchable category in Varna classifications. Scholars believe that the Varnas

system was never truly operational in society and there is no evidence

of it ever being a reality in Indian history. The practical division of

the society had always been in terms of Jatis (birth groups),

which are not based on any specific religious principle, but could vary

from ethnic origins to occupations to geographic areas. The Jātis

have been endogamous social groups without any fixed hierarchy but

subject to vague notions of rank articulated over time based on

lifestyle and social, political or economic status. Many of India's

major empires and dynasties like the Mauryas, Shalivahanas, Chalukyas, Kakatiyas among many others, were founded by people who would have been classified as Shudras, under the Varnas

system, as interpreted by the British rulers. It is well established

that by the 9th century, kings from all the four Varnas, including

Brahmins and Vaishyas, had occupied the highest seat in the monarchical

system in Hindu India, contrary to the Varna theory.

In many instances, as in Bengal, historically the kings and rulers had

been called upon, when required, to mediate on the ranks of Jātis, which might number in thousands all over the subcontinent and vary by region. In practice, the jātis may or may not fit into the Varna classes and many prominent Jatis, for example the Jats and Yadavs, straddled two Varnas i.e. Kshatriyas and Vaishyas, and the Varna status of Jātis itself was subject to articulation over time.

Starting with the 1901 Census of India led by colonial administrator Herbert Hope Risley, all the jātis were grouped under the theoretical varnas categories. According to political scientist Lloyd Rudolph, Risley believed that varna,

however ancient, could be applied to all the modern castes found in

India, and "[he] meant to identify and place several hundred million

Indians within it." The terms varna (conceptual classification based on occupation) and jāti (groups) are two distinct concepts: while varna is a theoretical four-part division, jāti

(community) refers to the thousands of actual endogamous social groups

prevalent across the subcontinent. The classical authors scarcely speak

of anything other than the varnas, as it provided a convenient shorthand; but a problem arises when colonial Indologists sometimes confuse the two.

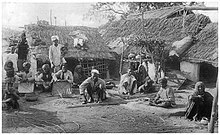

An image of a man and woman from the toddy-tapping community in Malabar from the manuscript

Seventy-two Specimens of Castes in India,

which consists of 72 full-color hand-painted images of men and women of

various religions, occupations and ethnic groups found in

Madura, India

in 1837, which confirms the popular perception and nature of caste as

Jati, before the British colonial authorities made it applicable only to

Hindus grouped under the

varna categories from the 1901 census onwards

Upon independence from Britain, the Indian Constitution listed 1,108 Jatis across the country as Scheduled Castes in 1950, for positive discrimination. This constitution would also ban discrimination of the basis of the caste, though its practice in India remained intact. The Untouchable communities are sometimes called Scheduled Castes, Dalit or Harijan in contemporary literature. In 2001, Dalits were 16.2% of India's population. Most of the 15 million bonded child workers are from the lowest castes. Independent India has witnessed caste-related violence. In 2005, government recorded approximately 110,000 cases of reported violent acts, including rape and murder, against Dalits. For 2012, the government recorded 651 murders, 3,855 injuries, 1,576 rapes, 490 kidnappings, and 214 cases of arson.

The socio-economic limitations of the caste system are reduced due to urbanisation and affirmative action. Nevertheless, the caste system still exists in endogamy and patrimony,

and thrives in the politics of democracy, where caste provides ready

made constituencies to politicians. The globalisation and economic

opportunities from foreign businesses has influenced the growth of

India's middle-class population. Some members of the Chhattisgarh Potter

Caste Community (CPCC) are middle-class urban professionals and no

longer potters unlike the remaining majority of traditional rural potter

members. There is persistence of caste in Indian politics.

Caste associations have evolved into caste-based political parties.

Political parties and the state perceive caste as an important factor

for mobilisation of people and policy development.

Studies by Bhatt and Beteille have shown changes in status,

openness, mobility in the social aspects of Indian society. As a result

of modern socio-economic changes in the country, India is experiencing

significant changes in the dynamics and the economics of its social

sphere.

While arranged marriages are still the most common practice in India,

the internet has provided a network for younger Indians to take control

of their relationships through the use of dating apps. This remains

isolated to informal terms, as marriage is not often achieved through

the use of these apps. Hypergamy

is still a common practice in India and Hindu culture. Men are expected

to marry within their caste, or one below, with no social

repercussions. If a woman marries into a higher caste, then her children

will take the status of their father. If she marries down, her family

is reduced to the social status of their son in law. In this case, the

women are bearers of the egalitarian principle of the marriage. There

would be no benefit in marrying a higher caste if the terms of the

marriage did not imply equality. However, men are systematically shielded from the negative implications of the agreement.

Geographical factors also determine adherence to the caste

system. Many Northern villages are more likely to participate in

exogamous marriage, due to a lack of eligible suitors within the same

caste. Women in North India

have been found to be less likely to leave or divorce their husbands

since they are of a relatively lower caste system, and have higher

restrictions on their freedoms. On the other hand, Pahari women, of the

northern mountains, have much more freedom to leave their husbands

without stigma. This often leads to better husbandry as his actions are

not protected by social expectations.

Chiefly among the factors influencing the rise of exogamy is the rapid urbanisation in India

experienced over the last century. It is well known that urban centers

tend to be less reliant on agriculture and are more progressive as a

whole. As India's cities boomed in population, the job market grew to

keep pace. Prosperity and stability were now more easily attained by an

individual, and the anxiety to marry quickly and effectively was

reduced. Thus, younger, more progressive generations of urban Indians

are less likely than ever to participate in the antiquated system of

arranged endogamy.

India has also implemented a form of Affirmative Action, locally

known as "reservation groups". Quota system jobs, as well as placements

in publicly funded colleges, hold spots for the 8% of India's minority,

and underprivileged groups. As a result, in states such as Tamil Nadu or those in the north-east,

where underprivileged populations predominate, over 80% of government

jobs are set aside in quotas. In education, colleges lower the marks

necessary for the Dalits to enter.

Nepal

The Nepali caste system resembles in some respects the Indian jāti system, with numerous jāti divisions with a varna system superimposed. Inscriptions attest the beginnings of a caste system during the Licchavi period. Jayasthiti Malla

(1382–1395) categorised Newars into 64 castes (Gellner 2001). A similar

exercise was made during the reign of Mahindra Malla (1506–1575). The

Hindu social code was later set up in the Gorkha Kingdom by Ram Shah (1603–1636).

Pakistan

McKim Marriott claims a social stratification that is hierarchical,

closed, endogamous and hereditary is widely prevalent, particularly in

western parts of Pakistan. Frederik Barth in his review of this system

of social stratification in Pakistan suggested that these are castes.

Sri Lanka

The caste system in Sri Lanka is a division of society into strata, influenced by the textbook varnas and jāti system found in India. Ancient Sri Lankan texts such as the Pujavaliya,

Sadharmaratnavaliya and Yogaratnakaraya and inscriptional evidence show

that the above hierarchy prevailed throughout the feudal period. The

repetition of the same caste hierarchy even as recently as the 18th

century, in the Kandyan-period Kadayimpoth – Boundary books as well indicates the continuation of the tradition right up to the end of Sri Lanka's monarchy.

Outside South Asia

Southeast Asia

Indonesia

Balinese

caste structure has been described as being based either on three

categories—the noble triwangsa (thrice born), the middle class of dwijāti (twice born), and the lower class of ekajāti (once born)--or on four castes

The Brahmana caste was further subdivided by Dutch ethnographers into

two: Siwa and Buda. The Siwa caste was subdivided into five: Kemenuh,

Keniten, Mas, Manuba and Petapan. This classification was to accommodate

the observed marriage between higher-caste Brahmana men with

lower-caste women. The other castes were similarly further

sub-classified by 19th-century and early-20th-century ethnographers

based on numerous criteria ranging from profession, endogamy or exogamy

or polygamy, and a host of other factors in a manner similar to castas in Spanish colonies such as Mexico, and caste system studies in British colonies such as India.

Philippines

In the Philippines, pre-colonial societies do not have a single

social structure. The class structures can be roughly categorised into

four types:

- Classless societies - egalitarian societies with no class structure. Examples include the Mangyan and the Kalanguya peoples.

- Warrior societies - societies where a distinct warrior class exists,

and whose membership depends on martial prowess. Examples include the Mandaya, Bagobo, Tagakaulo, and B'laan peoples who had warriors called the bagani or magani. Similarly, in the Cordillera highlands of Luzon, the Isneg and Kalinga peoples refer to their warriors as mengal or maingal. This society is typical for head-hunting ethnic groups or ethnic groups which had seasonal raids (mangayaw) into enemy territory.

- Petty plutocracies

- societies which have a wealthy class based on property and the

hosting of periodic prestige feasts. In some groups, it was an actual

caste whose members had specialised leadership roles, married only

within the same caste, and wore specialised clothing. These include the kadangyan of the Ifugao, Bontoc, and Kankanaey peoples, as well as the baknang of the Ibaloi people. In others, though wealth may give one prestige and leadership qualifications, it was not a caste per se.

- Principalities - societies with an actual ruling class and caste

systems determined by birthright. Most of these societies are either Indianized or Islamized to a degree. They include the larger coastal ethnic groups like the Tagalog, Kapampangan, Visayan, and Moro

societies. Most of them were usually divided into four to five caste

systems with different names under different ethnic groups that roughly

correspond to each other. The system was more or less feudalistic, with the datu ultimately having control of all the lands of the community. The land is subdivided among the enfranchised classes, the sakop or sa-op (vassals,

lit. "those under the power of another"). The castes were hereditary,

though they were not rigid. They were more accurately a reflection of

the interpersonal political relationships, a person is always the

follower of another. People can move up the caste system by marriage, by

wealth, or by doing something extraordinary; and conversely they can be

demoted, usually as criminal punishment or as a result of debt. Shamans

are the exception, as they are either volunteers, chosen by the ranking

shamans, or born into the role by innate propensity for it. They are

enumerated below from the highest rank to the lowest:

- Royalty - (Visayan: kadatoan) the datu and immediate descendants. They are often further categorised according to purity of lineage. The power of the datu

is dependent on the willingness of their followers to render him

respect and obedience. Most roles of the datu were judicial and

military. In case of an unfit datu, support may be withdrawn by his followers. Datu were almost always male, though in some ethnic groups like the Banwaon people, the female shaman (babaiyon) co-rules as the female counterpart of the datu.

- Nobility - (Visayan: tumao; Tagalog: maginoo; Kapampangan ginu; Tausug: bangsa mataas)

the ruling class, either inclusive of or exclusive of the royal family.

Most are descendants of the royal line or gained their status through

wealth or bravery in battle. They owned lands and subjects, from whom

they collected taxes.

- Shamans - (Visayan: babaylan; Tagalog: katalonan)

the spirit mediums, usually female or feminised men. While they weren't

technically a caste, they commanded the same respect and status as

nobility.

- Warriors - (Visayan: timawa; Tagalog: maharlika) the martial class. They could own land and subjects like the higher ranks, but were required to fight for the datu

in times of war. In some Filipino ethnic groups, they were often

tattooed extensively to record feats in battle and as protection against

harm. They were sometimes further subdivided into different classes,

depending on their relationship with the datu. They traditionally went on seasonal raids on enemy settlements.

- Commoners and slaves - (Visayan, Maguindanao: ulipon; Tagalog: alipin; Tausug: kiapangdilihan; Maranao: kakatamokan)

- the lowest class composed of the rest of the community who were not

part of the enfranchised classes. They were further subdivided into the

commoner class who had their own houses, the servants who lived in the

houses of others, and the slaves who were usually captives from raids,

criminals, or debtors. Most members of this class were equivalent to the

European serf class, who paid taxes and can be conscripted to communal tasks, but were more or less free to do as they please.

East Asia

China and Mongolia

During the period of Yuan Dynasty, ruler Kublai Khan enforced a Four Class System, which was a legal caste system. The order of four classes of people in descending order were:

Today, the Hukou system is argued by various Western sources to be the current caste system of China.

Tibet

There is significant controversy over the social classes of Tibet, especially with regards to the serfdom in Tibet controversy.

Heidi Fjeld [no]

has put forth the argument that pre-1950s Tibetan society was

functionally a caste system, in contrast to previous scholars who

defined the Tibetan social class system as similar to European feudal

serfdom, as well as non-scholarly western accounts which seek to

romanticise a supposedly 'egalitarian' ancient Tibetan society.

Japan

In Japan's history, social strata based on inherited position rather

than personal merit, were rigid and highly formalised in a system called

mibunsei (身分制). At the top were the Emperor and Court nobles (kuge), together with the Shōgun and daimyō. Below them, the population was divided into four classes: samurai,

peasants, craftsmen and merchants. Only samurai were allowed to bear

arms. A samurai had a right to kill any peasants, craftsman or merchant

who he felt were disrespectful. Merchants were the lowest caste because

they did not produce any products. The castes were further sub-divided;

for example, peasants were labelled as furiuri, tanagari, mizunomi-byakusho among others. As in Europe, the castes and sub-classes were of the same race, religion and culture.

Howell, in his review of Japanese

society notes that if a Western power had colonised Japan in the 19th

century, they would have discovered and imposed a rigid four-caste

hierarchy in Japan.

De Vos and Wagatsuma observe that Japanese society had a

systematic and extensive caste system. They discuss how alleged caste

impurity and alleged racial inferiority, concepts often assumed to be

different, are superficial terms, and are due to identical inner

psychological processes, which expressed themselves in Japan and

elsewhere.

Endogamy was common because marriage across caste lines was socially unacceptable.

Japan had its own untouchable caste, shunned and ostracised, historically referred to by the insulting term eta, now called burakumin. While modern law has officially abolished the class hierarchy, there are reports of discrimination against the buraku or burakumin underclasses. The burakumin are regarded as "ostracised". The burakumin are one of the main minority groups in Japan, along with the Ainu of Hokkaidō and those of Korean or Chinese descent.

Korea

A

typical Yangban family scene from 1904. The Yoon family had an enduring

presence in Korean politics from the 1800s until the 1970s.

The baekjeong (백정) were an "untouchable" outcaste of Korea. The meaning today is that of butcher. It originates in the Khitan invasion of Korea in the 11th century. The defeated Khitans

who surrendered were settled in isolated communities throughout Goryeo

to forestall rebellion. They were valued for their skills in hunting,

herding, butchering, and making of leather, common skill sets among

nomads. Over time, their ethnic origin was forgotten, and they formed

the bottom layer of Korean society.

In 1392, with the foundation of the Confucian Joseon dynasty, Korea systemised its own native class system. At the top were the two official classes, the Yangban, which literally means "two classes". It was composed of scholars (munban) and warriors (muban). Scholars had a significant social advantage over the warriors. Below were the jung-in

(중인-中人: literally "middle people". This was a small class of

specialised professions such as medicine, accounting, translators,

regional bureaucrats, etc. Below that were the sangmin (상민-常民: literally 'commoner'), farmers working their own fields. Korea also had a serf population known as the nobi.

The nobi population could fluctuate up to about one third of the

population, but on average the nobi made up about 10% of the total

population. In 1801, the vast majority of government nobi were emancipated, and by 1858 the nobi population stood at about 1.5% of the total population of Korea. The hereditary nobi system was officially abolished around 1886–87 and the rest of the nobi system was abolished with the Gabo Reform of 1894, but traces remained until 1930.

The opening of Korea to foreign Christian missionary activity in the late 19th century saw some improvement in the status of the baekjeong.

However, everyone was not equal under the Christian congregation, and

even so protests erupted when missionaries tried to integrate baekjeong into worship, with non-baekjeong finding this attempt insensitive to traditional notions of hierarchical advantage. Around the same time, the baekjeong began to resist open social discrimination. They focused on social and economic injustices affecting them, hoping to create an egalitarian

Korean society. Their efforts included attacking social discrimination

by upper class, authorities, and "commoners", and the use of degrading

language against children in public schools.

With the Gabo reform of 1896, the class system of Korea was officially abolished. Following the collapse of the Gabo government, the new cabinet, which became the Gwangmu government after the establishment of the Korean Empire,

introduced systematic measures for abolishing the traditional class

system. One measure was the new household registration system,

reflecting the goals of formal social equality,

which was implemented by the loyalists' cabinet. Whereas the old

registration system signified household members according to their

hierarchical social status, the new system called for an occupation.

While most Koreans by then had surnames and even bongwan, although still substantial number of cheonmin, mostly consisted of serfs and slaves, and untouchables

did not. According to the new system, they were then required to fill

in the blanks for surname in order to be registered as constituting

separate households. Instead of creating their own family name, some

cheonmins appropriated their masters' surname, while others simply took

the most common surname and its bongwan in the local area. Along with

this example, activists within and outside the Korean government had

based their visions of a new relationship between the government and

people through the concept of citizenship, employing the term inmin ("people") and later, kungmin ("citizen").

North Korea

The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

reported that "Every North Korean citizen is assigned a heredity-based

class and socio-political rank over which the individual exercises no

control but which determines all aspects of his or her life." Called Songbun, Barbara Demick describes this "class structure" as an updating of the hereditary "caste system", a combination of Confucianism and Stalinism.

It originated in 1946 and was entrenched by the 1960s, and consisted of

53 categories ranging across three classes: loyal, wavering, and

impure. The privileged "loyal" class included members of the Korean Workers' Party and Korean People's Army officers' corps, the wavering class included peasants, and the impure class included collaborators with Imperial Japan and landowners.

She claims that a bad family background is called "tainted blood", and

that by law this "tainted blood" lasts three generations.

West Asia

Kurdistan

Yazidis

There are three hereditary groups, often called castes, in Yazidism. Membership in the Yazidi society and a caste is conferred by birth. Pîrs and Sheikhs are the priestly castes, which are represented by many sacred lineages (Kurdish: Ocax).

Sheikhs are in charge of both religious and administrative functions

and are divided into three endogamous houses, Şemsanî, Adanî and Qatanî

who are in turn divided into lineages. The Pîrs are in charge of purely

religious functions and traditionally consist of 40 lineages or clans,

but approximately 90 appellations of Pîr lineages have been found, which

may have been a result of new sub-lineages arising and number of clans

increasing over time due to division as Yazidis settled in different

places and countries. Division could occur in one family, if there were a

few brothers in one clan, each of them could become the founder of

their own Pîr sub-clan (Kurdish: ber). Mirîds are the lay caste and are divided into tribes, who are each affiliated to a Pîr and a Sheikh priestly lineage assigned to the tribe.

Iran

Pre-Islamic Sassanid

society was immensely complex, with separate systems of social

organisation governing numerous different groups within the empire. Historians believe society comprised four social classes, which linguistic analysis indicates may have been referred to collectively as "pistras". The classes, from highest to lowest status, were priests (Persian: Asravan), warriors (Persian: Arteshtaran), secretaries (Persian: Dabiran), and commoners (Persian: Vastryoshan).

Yemen

In Yemen there exists a hereditary caste, the African-descended Al-Akhdam

who are kept as perennial manual workers. Estimates put their number at

over 3.5 million residents who are discriminated, out of a total Yemeni

population of around 22 million.

Africa

Various sociologists have reported caste systems in Africa.

The specifics of the caste systems have varied in ethnically and

culturally diverse Africa, however the following features are common –

it has been a closed system of social stratification, the social status

is inherited, the castes are hierarchical, certain castes are shunned

while others are merely endogamous and exclusionary. In some cases, concepts of purity and impurity by birth have been prevalent in Africa. In other cases, such as the Nupe of Nigeria, the Beni Amer of East Africa, and the Tira of Sudan, the exclusionary principle has been driven by evolving social factors.

West Africa

A

Griot,

who have been described as an endogamous caste of West Africa who

specialise in oral story telling and culture preservation. They have

been also referred to as the bard caste.

Among the Igbo of Nigeria – especially Enugu, Anambra, Imo, Abia, Ebonyi, Edo and Delta states of the country – scholar Elijah Obinna finds that the Osu caste system

has been and continues to be a major social issue. The Osu caste is

determined by one's birth into a particular family irrespective of the

religion practised by the individual. Once born into Osu caste, this

Nigerian person is an outcast, shunned and ostracised, with limited

opportunities or acceptance, regardless of his or her ability or merit.

Obinna discusses how this caste system-related identity and power is

deployed within government, Church and indigenous communities.

The osu class systems of eastern Nigeria and southern Cameroon are derived from indigenous religious beliefs and discriminate against the "Osus" people as "owned by deities" and outcasts.

The Songhai

economy was based on a caste system. The most common were metalworkers,

fishermen, and carpenters. Lower caste participants consisted of mostly

non-farm working immigrants, who at times were provided special

privileges and held high positions in society. At the top were noblemen

and direct descendants of the original Songhai people, followed by

freemen and traders.

In a review of social stratification systems in Africa, Richter

reports that the term caste has been used by French and American

scholars to many groups of West African artisans. These groups have been

described as inferior, deprived of all political power, have a specific

occupation, are hereditary and sometimes despised by others. Richter

illustrates caste system in Ivory Coast,

with six sub-caste categories. Unlike other parts of the world,

mobility is sometimes possible within sub-castes, but not across caste

lines. Farmers and artisans have been, claims Richter, distinct castes.

Certain sub-castes are shunned more than others. For example, exogamy is

rare for women born into families of woodcarvers.

Similarly, the Mandé societies in Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Senegal and Sierra Leone have social stratification systems that divide society by ethnic ties. The Mande class system regards the jonow slaves as inferior. Similarly, the Wolof in Senegal is divided into three main groups, the geer (freeborn/nobles), jaam (slaves and slave descendants) and the underclass neeno. In various parts of West Africa, Fulani societies also have class divisions. Other castes include Griots, Forgerons, and Cordonniers.

Tamari has described endogamous castes of over fifteen West African peoples, including the Tukulor, Songhay, Dogon, Senufo, Minianka, Moors, Manding, Soninke, Wolof, Serer, Fulani, and Tuareg. Castes appeared among the Malinke people no later than 14th century, and was present among the Wolof and Soninke, as well as some Songhay and Fulani populations, no later than 16th century. Tamari claims that wars, such as the Sosso-Malinke war described in the Sunjata epic, led to the formation of blacksmith and bard castes among the people that ultimately became the Mali empire.

As West Africa evolved over time, sub-castes emerged that

acquired secondary specialisations or changed occupations. Endogamy was

prevalent within a caste or among a limited number of castes, yet castes

did not form demographic isolates according to Tamari. Social status

according to caste was inherited by off-springs automatically; but this

inheritance was paternal. That is, children of higher caste men and

lower caste or slave concubines would have the caste status of the

father.

Central Africa

Ethel M. Albert in 1960 claimed that the societies in Central Africa were caste-like social stratification systems. Similarly, in 1961, Maquet notes that the society in Rwanda and Burundi can be best described as castes. The Tutsi, noted Maquet, considered themselves as superior, with the more numerous Hutu and the least numerous Twa

regarded, by birth, as respectively, second and third in the hierarchy

of Rwandese society. These groups were largely endogamous, exclusionary

and with limited mobility.

Horn of Africa

The

Madhiban (Midgan) specialise in leather occupation. Along with the Tumal and Yibir, they are collectively known as

sab.

In a review published in 1977, Todd reports that numerous scholars

report a system of social stratification in different parts of Africa

that resembles some or all aspects of caste system. Examples of such

caste systems, he claims, are to be found in Ethiopia in communities such as the Gurage and Konso.

He then presents the Dime of Southwestern Ethiopia, amongst whom there

operates a system which Todd claims can be unequivocally labelled as

caste system. The Dime have seven castes whose size varies considerably.

Each broad caste level is a hierarchical order that is based on notions

of purity, non-purity and impurity. It uses the concepts of defilement

to limit contacts between caste categories and to preserve the purity of

the upper castes. These caste categories have been exclusionary,

endogamous and the social identity inherited. Alula Pankhurst has published a study of caste groups in SW Ethiopia.

Among the Kafa,

there were also traditionally groups labelled as castes. "Based on

research done before the Derg regime, these studies generally presume

the existence of a social hierarchy similar to the caste system. At the

top of this hierarchy were the Kafa, followed by occupational groups

including blacksmiths (Qemmo), weavers (Shammano), bards (Shatto),

potters, and tanners (Manno). In this hierarchy, the Manjo were commonly

referred to as hunters, given the lowest status equal only to slaves."

The Borana Oromo of southern Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa

also have a class system, wherein the Wata, an acculturated

hunter-gatherer group, represent the lowest class. Though the Wata today

speak the Oromo language, they have traditions of having previously spoken another language before adopting Oromo.

The traditionally nomadic Somali people are divided into clans, wherein the Rahanweyn agro-pastoral clans and the occupational clans such as the Madhiban were traditionally sometimes treated as outcasts. As Gabboye, the Madhiban along with the Yibir and Tumaal (collectively referred to as sab) have since obtained political representation within Somalia, and their general social status has improved with the expansion of urban centers.

Europe

European feudalism with its rigid aristocracy can also be considered as a caste system.

Basque region

For centuries, through the modern times, the majority regarded Cagots who lived primarily in the Basque region

of France and Spain as an inferior caste, the untouchables. While they

had the same skin color and religion as the majority, in the churches

they had to use segregated doors, drink from segregated fonts, and

receive communion on the end of long wooden spoons. It was a closed

social system. The socially isolated Cagots were endogamous, and chances

of social mobility non-existent.

United Kingdom

In July 2013, the UK government announced its intention to amend the Equality Act 2010,

to "introduce legislation on caste, including any necessary exceptions

to the caste provisions, within the framework of domestic discrimination

law". Section 9(5) of the Equality Act 2010 provides that "a Minister may by order

amend the statutory definition of race to include caste and may provide

for exceptions in the Act to apply or not to apply to caste".

From September 2013 to February 2014, Meena Dhanda led a project on "Caste in Britain" for the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC).

Americas

Latin America

The existence of a caste system based on the concept of casta in Latin America under colonial Spain has been raised and contemporarily contested, distinguishing it from more general colonial or racial discrimination.

United States

A survey on caste discrimination conducted by Equality Labs

found 67% of Indian Dalits living in the US reporting that they faced

caste-based harassment at the workplace, and 27% reporting verbal or

physical assault based on their caste.

In 2023, Seattle became the first city in the United States to ban discrimination based on caste.

In the opinion of W. Lloyd Warner, discrimination in the Southern United States in the 1930s against Blacks was similar to Indian castes in such features as residential segregation and marriage restrictions. In her 2020 book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, journalist Isabel Wilkerson used caste as an analogy to understand racial discrimination in the United States.

Gerald D. Berreman

contrasted the differences between discrimination in the United States

and India. In India, there are complex religious features which make up

the system, whereas in the United States race and color are the basis

for differentiation. The caste systems in India and the United States

have higher groups which desire to retain their positions for themselves

and thus perpetuate the two systems.

The process of creating a homogenized society by social

engineering in both India and the Southern US has created other

institutions that have made class distinctions among different groups

evident. Anthropologist James C. Scott elaborates on how "global capitalism

is perhaps the most powerful force for homogenization, whereas the

state may be the defender of local difference and variety in some

instances".

The caste system, a relic of feudalistic economic systems, emphasizes

differences between socio-economic classes that are obviated by openly

free market capitalistic economic systems, which reward individual

initiative, enterprise, merit, and thrift, thereby creating a path for

social mobility. When the feudalistic slave economy of the southern United States was dismantled, even Jim Crow laws did not prevent the economic success of many industrious African Americans, including millionaire women like Maggie Walker, Annie Malone, and Madame C.J. Walker. Parts of the United States are sometimes divided by race and class status despite the national narrative of integration.

Caste in sociology and entomology

The

initial observational studies of the division of labour in ant colonies

attempted to demonstrate that ants specialized in tasks that were best

suited to their size when they emerged from the pupae stage into the

adult stage. A large proportion of the experimental work was done in species that showed strong variation in size.

As the size of an adult was fixed for life, workers of a specific size

range came to be called a "caste," calling up the traditional caste

system in India in which a human's standing in society was decided at

birth.

The notion of caste encouraged a link between scholarship in

entomology and sociology because it served as an example of a division

of labour in which the participants seemed to be uncompromisingly

adapted to special functions and sometimes even unique environments.

To bolster the concept of caste, entomologists and sociologists

referred to the complementary social or natural parallel and thereby

appeared to generalize the concept and give it an appearance of

familiarity. In the late 19th- and early 20th centuries, the perceived similarities between the Indian caste system and caste polymorphism

in insects were used to create a correspondence or parallelism for the

purpose of explaining or clarifying racial stratification in human

societies; the explanations came particularly to be employed in the

United States. Ideas from heredity and natural selection

influenced some sociologists who believed that some groups were

predetermined to belong to a lower social or occupational status. Chiefly through the work of W. Lloyd Warner at the University of Chicago, a group of sociologists sharing similar principles came to evolve around the creed of caste in the 1930s and 1940s.

The ecologically-oriented sociologist Robert E. Park,

although attributing more weight to environmental explanations than the

biological nonetheless believed that there were obstacles to the

assimilation of blacks into American society and that an "accommodation

stage" in a biracially organized caste system was required before full

assimilation. He did disavow his position in 1937, suggesting that blacks were a minority and not a caste. The Indian sociologist Radhakamal Mukerjee was influenced by Robert E. Park and adopted the concept of "caste" to describe race relations in the US.

According to anthropologist Diane Rodgers, Mukerjee "proceeded to

suggest that a caste system should be correctly instituted in the (US)

South to ease race relations." Mukerjee often employed both entomological and sociological data and clues to describe caste systems.

He wrote "while the fundamental industries of man are dispersed

throughout the insect world, the same kind of polymorphism appears again

and again in different species of social insects which have reacted in

the same manner as man, under the influence of the same environment, to

ensure the supply and provision of subsistence."

Comparing the caste system in India to caste polymorphism in insects,

he noted, "where we find the organization of social insects developed to

perfection, there also has been seen among human associations a minute

and even rigid specialization of functions, along with ant- and bee-like

societal integrity and cohesiveness." He considered the "resemblances between insect associations and caste-ridden societies" to be striking enough to be "amusing."