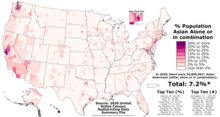

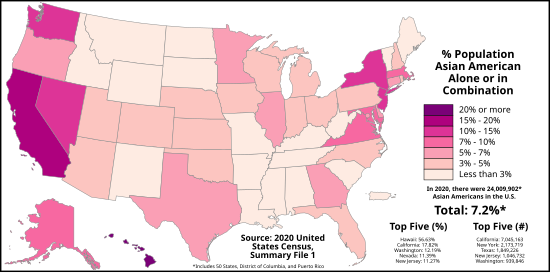

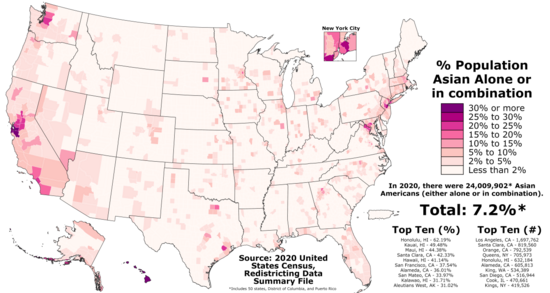

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous peoples of the continent of Asia, the usage of the term "Asian" by the United States Census Bureau only includes people with origins or ancestry from the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent and excludes people with ethnic origins in certain parts of Asia, including West Asia who are now categorized as Middle Eastern Americans. The "Asian" census category includes people who indicate their race(s) on the census as "Asian" or reported entries such as "Chinese, Indian, Filipino, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Korean, Japanese, Pakistani, Malaysian, and Other Asian". In 2020, Americans who identified as Asian alone (19,886,049) or in combination with other races (4,114,949) made up 7.2% of the U.S. population.

Chinese, Indian, and Filipino Americans make up the largest share of the Asian American population with 5 million, 4.3 million, and 4 million people respectively. These numbers equal 23%, 20%, and 18% of the total Asian American population, or 1.5% and 1.2% of the total U.S. population.

Although migrants from Asia have been in parts of the contemporary United States since the 17th century, large-scale immigration did not begin until the mid-19th century. Nativist immigration laws during the 1880s–1920s excluded various Asian groups, eventually prohibiting almost all Asian immigration to the continental United States. After immigration laws were reformed during the 1940s–1960s, abolishing national origins quotas, Asian immigration increased rapidly. Analyses of the 2010 census have shown that Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial group in the United States.

Terminology

As with other racial and ethnicity-based terms, formal and common usage have changed markedly through the short history of this term. Prior to the late 1960s, people of Asian ancestry were usually referred to as Yellow, Oriental, Asiatic, or Mongoloid. Additionally, the American definition of 'Asian' originally included West Asian ethnic groups, particularly Turkish Americans, Armenian Americans, Assyrian Americans, Iranian Americans, Kurdish Americans, Jewish Americans, and certain Arab Americans, although in modern times, these groups are now considered Middle Eastern American. The term "Asian American" was coined by historian-activists Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee in 1968 during the founding of the Asian American Political Alliance, and they were also credited with popularizing the term, which meant to be used to frame a new "inter-ethnic-pan-Asian American self-defining political group". This effort was part of New Left anti-war and anti-imperialist activism, directly opposing what was viewed as an unjust Vietnam War.

Prior to being included in the "Asian" category in the 1980s, many Americans of South Asian descent usually classified themselves as Caucasian or other. Changing patterns of immigration and an extensive period of exclusion of Asian immigrants have resulted in demographic changes that have in turn affected the formal and common understandings of what defines Asian American. For example, since the removal of restrictive "national origins" quotas in 1965, the Asian American population has diversified greatly to include more of the peoples with ancestry from various parts of Asia.

Today, "Asian American" is the accepted term for most formal purposes, such as government and academic research, although it is often shortened to Asian in common usage. The most commonly used definition of Asian American is the U.S. Census Bureau definition, which includes all people with origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This is chiefly because the census definitions determine many governmental classifications, notably for equal opportunity programs and measurements.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, "Asian person" in the United States is most often thought of as a person of East Asian descent. In vernacular usage, "Asian" is usually used to refer to those of East Asian descent or anyone else of Asian descent with epicanthic eyefolds. This differs from the U.S. census definition and the Asian American Studies departments in many universities consider all those of East, South, or Southeast Asian descent to be "Asian".

Census definition

In the U.S. census, people with origins or ancestry in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent are classified as part of the Asian race; while those with origins or ancestry in West Asia (Israelis, Turks, Persians, Kurds, Assyrians, Arabs, etc.), and the Caucasus (Georgians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Chechens, Circassians, etc.) are classified as "white" or "Middle Eastern", and those with origins from Central Asia (Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmens, Tajiks, Kyrgyz, Afghans, etc.) are not mentioned in racial definitions provided by the United States Census Bureau. As such, "Asian" and "African" ancestry are seen as racial categories only for the purpose of the census, with the definition referring to ancestry from parts of the Asian and African continents outside of West Asia, North Africa, and Central Asia.

In 1980 and before, census forms listed particular Asian ancestries as separate groups, along with white and black or negro. Asian Americans had also been classified as "other". In 1977, the federal Office of Management and Budget issued a directive requiring government agencies to maintain statistics on racial groups, including on "Asian or Pacific Islander". By the 1990 census, "Asian or Pacific Islander (API)" was included as an explicit category, although respondents had to select one particular ancestry as a subcategory. Beginning with the 2000 census, two separate categories were used: "Asian American" and "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander".

Debates and criticism

The definition of Asian American has variations that derive from the use of the word American in different contexts. Immigration status, citizenship (by birthright and by naturalization), acculturation, and language ability are some variables that are used to define American for various purposes and may vary in formal and everyday usage. For example, restricting American to include only U.S. citizens conflicts with discussions of Asian American businesses, which generally refer both to citizen and non-citizen owners.

In a PBS interview from 2004, a panel of Asian American writers discussed how some groups include people of Middle Eastern descent in the Asian American category. Asian American author Stewart Ikeda has noted, "The definition of 'Asian American' also frequently depends on who's asking, who's defining, in what context, and why... the possible definitions of 'Asian-Pacific American' are many, complex, and shifting... some scholars in Asian American Studies conferences suggest that Russians, Iranians, and Israelis all might fit the field's subject of study." Jeff Yang, of The Wall Street Journal, writes that the panethnic definition of Asian American is a unique American construct, and as an identity is "in beta". The majority of Asian Americans feel ambivalence about the term "Asian American" as a term by which to identify themselves. Pyong Gap Min, a sociologist and Professor of Sociology at Queens College, has stated the term is merely political, used by Asian American activists and further reinforced by the government. Beyond that, he feels that South Asians and East Asians do not have commonalities in "culture, physical characteristics, or pre-migrant historical experiences".

Scholars have grappled with the accuracy, correctness, and usefulness of the term Asian American. The term "Asian" in Asian American most often comes under fire for only encompassing some of the diverse peoples of Asia, and for being considered a racial category instead of a non-racial "ethnic" category. This is namely due to the categorization of the racially different South Asians and East Asians as part of the same "race". Furthermore, it has been noted that West Asians (whom are not considered "Asian" under the U.S. census) share some cultural similarities with Indians but very little with East Asians, with the latter two groups being classified as "Asian". Scholars have also found it difficult to determine why Asian Americans are considered a "race" while Americans of Hispanic and Latino heritage are a non-racial "ethnic group", given how the category of Asian Americans similarly comprises people with diverse origins. However, it has been argued that South Asians and East Asians can be "justifiably" grouped together because of Buddhism's origins in South Asia.

In contrast, leading social sciences and humanities scholars of race and Asian American identity point out that because of the racial constructions in the United States, including the social attitudes toward race and those of Asian ancestry, Asian Americans have a "shared racial experience." Because of this shared experience, the term Asian American is argued as still being a useful panethnic category because of the similarity of some experiences among Asian Americans, including stereotypes specific to people in this category. Despite this, others have stated that many Americans do not treat all Asian Americans equally, highlighting the fact that "Asian American" is generally synonymous with people of East Asian descent, thereby excluding people of Southeast Asian and South Asian origin. Some South and Southeast Asian Americans may not identify with the Asian American label, instead describing themselves as "Brown Asians" or simply "Brown", due to the perceived racial and cultural differences between them and East Asian Americans.

Demographics

The demographics of Asian Americans describe a heterogeneous group of people in the United States who can trace their ancestry to one or more countries in East, South, or Southeast Asia. Because they compose 7.3% of the entire U.S. population, the diversity of the group is often disregarded in media and news discussions of "Asians" or of "Asian Americans". While there are some commonalities across ethnic subgroups, there are significant differences among different Asian ethnicities that are related to each group's history. The Asian American population is greatly urbanized, with nearly three-quarters of them living in metropolitan areas with population greater than 2.5 million. As of July 2015, California had the largest population of Asian Americans of any state, and Hawaii was the only state where Asian Americans were the majority of the population.

The demographics of Asian Americans can further be subdivided into, as listed in alphabetical order:

- East Asian Americans, including Chinese Americans, Hong Kong Americans, Japanese Americans, Korean Americans, Macanese Americans, Mongolian Americans, Ryukyuan Americans, Taiwanese Americans, and Tibetan Americans.

- South Asian Americans, including Bangladeshi Americans, Bhutanese Americans, Indian Americans, Indo-Caribbean Americans, Indo-Fijian Americans, Maldivian Americans, Nepalese Americans, Pakistani Americans, and Sri Lankan Americans.

- Southeast Asian Americans, including Bruneian Americans, Burmese Americans, Cambodian Americans, Filipino Americans, Hmong Americans, Indonesian Americans, Iu Mien Americans, Karen Americans, Laotian Americans, Malaysian Americans, Singaporean Americans, Thai Americans, Timorese Americans, and Vietnamese Americans.

This grouping is by country of origin before immigration to the United States, and not necessarily by ethnicity, as for example (nonexclusive), Singaporean Americans may be of Chinese, Indian, or Malay descent.

Asian Americans include multiracial or mixed race persons with origins or ancestry in both the above groups and another race, or multiple of the above groups.

Language

In 2010, there were 2.8 million people (age 5 and older) who spoke one of the Chinese languages at home; after the Spanish language, it is the third most common language in the United States. Other sizable Asian languages are Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Korean, with all three having more than 1 million speakers in the United States.

In 2012, Alaska, California, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Texas, and Washington were publishing election material in Asian languages in accordance with the Voting Rights Act; these languages include Tagalog, Mandarin Chinese, Vietnamese, Spanish, Hindi, and Bengali. Election materials were also available in Gujarati, Japanese, Khmer, Korean, and Thai. A 2013 poll found that 48 percent of Asian Americans considered media in their native language as their primary news source.

The 2000 census found the more prominent languages of the Asian American community to include the Chinese languages (Cantonese, Taishanese, and Hokkien), Tagalog, Vietnamese, Korean, Japanese, Hindi, Urdu, Telugu, and Gujarati. In 2008, the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Tagalog, and Vietnamese languages are all used in elections in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington state.

Religion

A 2012 Pew Research Center study found the following breakdown of religious identity among Asian Americans:

- 42% Christian

- 26% Unaffiliated with any religion

- 14% Buddhist

- 10% Hindu

- 4% Muslim

- 2% other religion

- 1% Sikh

Religious trends

The percentage of Christians among Asian Americans has sharply declined since the 1990s, chiefly as a result of large-scale immigration from countries in which Christianity is a minority religion (China and India in particular). In 1990, 63% of the Asian Americans identified as Christians, while in 2001 only 43% did. This development has been accompanied by a rise in traditional Asian religions, with the people identifying with them doubling during the same decade.

History

Early immigration

Because Asian Americans or their ancestors immigrated to the United States from many different countries, each Asian American population has its own unique immigration history.

Filipinos have been in the territories that would become the United States since the 16th century. In 1635, an "East Indian" is listed in Jamestown, Virginia; preceding wider settlement of Indian immigrants on the East Coast in the 1790s and the West Coast in the 1800s. In 1763, Filipinos established the small settlement of Saint Malo, Louisiana, after fleeing mistreatment aboard Spanish ships. Since there were no Filipino women with them, these "Manilamen", as they were known, married Cajun and Native American women. The first Japanese person to come to the United States, and stay any significant period of time was Nakahama Manjirō who reached the East Coast in 1841, and Joseph Heco became the first Japanese American naturalized U.S. citizen in 1858.

Chinese sailors first came to Hawaii in 1789, a few years after Captain James Cook came upon the island. Many settled and married Hawaiian women. Most Chinese, Korean and Japanese immigrants in Hawaii or San Francisco arrived in the 19th century as laborers to work on sugar plantations or construction place. There were thousands of Asians in Hawaii when it was annexed to the United States in 1898. Later, Filipinos also came to work as laborers, attracted by the job opportunities, although they were limited. Ryukyuans would start migrating to Hawaii in 1900.

Large-scale migration from Asia to the United States began when Chinese immigrants arrived on the West Coast in the mid-19th century. Forming part of the California gold rush, these early Chinese immigrants participated intensively in the mining business and later in the construction of the transcontinental railroad. By 1852, the number of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco had jumped to more than 20,000. A wave of Japanese immigration to the United States began after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. In 1898, all Filipinos in the Philippine Islands became American nationals when the United States took over colonial rule of the islands from Spain following the latter's defeat in the Spanish–American War.

Exclusion era

Under United States law during this period, particularly the Naturalization Act of 1790, only "free white persons" were eligible to naturalize as American citizens. Ineligibility for citizenship prevented Asian immigrants from accessing a variety of rights, such as voting. Bhicaji Balsara became the first known Indian-born person to gain naturalized U.S. citizenship. Balsara's naturalization was not the norm but an exception; in a pair of cases, Ozawa v. United States (1922) and United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), the Supreme Court upheld the racial qualification for citizenship and ruled that Asians were not "white persons". Second-generation Asian Americans, however, could become U.S. citizens due to the birthright citizenship clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; this guarantee was confirmed as applying regardless of race or ancestry by the Supreme Court in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898).

From the 1880s to the 1920s, the United States passed laws inaugurating an era of exclusion of Asian immigrants. Although the exact number of Asian immigrants was small compared to that of immigrants from other regions, much of it was concentrated in the West, and the increase caused some nativist sentiment which was known as the "yellow peril". Congress passed restrictive legislation which prohibited nearly all Chinese immigration to the United States in the 1880s. Japanese immigration was sharply curtailed by a diplomatic agreement in 1907. The Asiatic Barred Zone Act in 1917 further barred immigration from nearly all of Asia, the "Asiatic Zone". The Immigration Act of 1924 provided that no "alien ineligible for citizenship" could be admitted as an immigrant to the United States, consolidating the prohibition of Asian immigration.

World War II

President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, resulting in the internment of Japanese Americans, among others. Over 100,000 people of Japanese descent, mostly on the West Coast, were forcibly removed, in an action later considered ineffective and racist.

Postwar immigration

World War II-era legislation and judicial rulings gradually increased the ability of Asian Americans to immigrate and become naturalized citizens. Immigration rapidly increased following the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965 as well as the influx of refugees from conflicts occurring in Southeast Asia such as the Vietnam War. Asian American immigrants have a significant percentage of individuals who have already achieved professional status, a first among immigration groups.

The number of Asian immigrants to the United States "grew from 491,000 in 1960 to about 12.8 million in 2014, representing a 2,597 percent increase." Asian Americans were the fastest-growing racial group between 2000 and 2010. By 2012, more immigrants came from Asia than from Latin America. In 2015, Pew Research Center found that from 2010 to 2015 more immigrants came from Asia than from Latin America, and that since 1965; Asians have made up a quarter of all immigrants to the United States.

Asians have made up an increasing proportion of the foreign-born Americans: "In 1960, Asians represented 5 percent of the U.S. foreign-born population; by 2014, their share grew to 30 percent of the nation's 42.4 million immigrants." As of 2016, "Asia is the second-largest region of birth (after Latin America) of U.S. immigrants." In 2013, China surpassed Mexico as the top single country of origin for immigrants to the U.S. Asian immigrants "are more likely than the overall foreign-born population to be naturalized citizens"; in 2014, 59% of Asian immigrants had U.S. citizenship, compared to 47% of all immigrants. Postwar Asian immigration to the U.S. has been diverse: in 2014, 31% of Asian immigrants to the U.S. were from East Asia (predominantly China and Korea); 27.7% were from South Asia (predominantly India); 32.6% were from Southeastern Asia (predominantly the Philippines and Vietnam); and 8.3% were from Western Asia.

Asian American movement

Prior to the 1960s, Asian immigrants and their descendants had organized and agitated for social or political purposes according to their particular ethnicity: Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, or Asian Indian. The Asian American movement (a term coined by the Japanese American Yuji Ichioka and the Chinese American Emma Gee) gathered all those groups into a coalition, recognizing that they shared common problems with racial discrimination and common opposition to American imperialism, particularly in Asia. The movement developed during the 1960s, inspired in part by the Civil Rights Movement and the protests against the Vietnam War. "Drawing influences from the Black Power and antiwar movements, the Asian American movement forged a coalitional politics that united Asians of varying ethnicities and declared solidarity with other Third World people in the United States and abroad. Segments of the movement struggled for community control of education, provided social services and defended affordable housing in Asian ghettoes, organized exploited workers, protested against U.S. imperialism, and built new multiethnic cultural institutions." William Wei described the movement as "rooted in a past history of oppression and a present struggle for liberation." The movement as such was most active during the 1960s and 1970s.

Increasingly Asian American students demanded university-level research and teaching into Asian history and interaction with the United States. They support multiculturalism and support affirmative action but oppose colleges' quota on Asian students viewed as discriminatory.

Notable contributions

Arts and entertainment

Asian Americans have been involved in the entertainment industry since the first half of the 19th century, when Chang and Eng Bunker (the original "Siamese Twins") became naturalized citizens. Throughout the 20th century, acting roles in television, film, and theater were relatively few, and many available roles were for narrow, stereotypical characters. More recently, young Asian American comedians and film-makers have found an outlet on YouTube allowing them to gain a strong and loyal fanbase among their fellow Asian Americans. There have been several Asian American-centric television shows in American media, beginning with Mr. T and Tina in 1976, and as recent as Fresh Off the Boat in 2015.

In the Pacific, American beatboxer of Hawaii Chinese descent Jason Tom co-founded the Human Beatbox Academy to perpetuate the art of beatboxing through outreach performances, speaking engagements and workshops in Honolulu, the westernmost and southernmost major U.S. city of the 50th U.S. state of Hawaii.

Business

When Asian Americans were largely excluded from labor markets in the 19th century, they started their own businesses. They have started convenience and grocery stores, professional offices such as medical and law practices, laundries, restaurants, beauty-related ventures, hi-tech companies, and many other kinds of enterprises, becoming very successful and influential in American society. They have dramatically expanded their involvement across the American economy. Asian Americans have been disproportionately successful in the hi-tech sectors of California's Silicon Valley, as evidenced by the Goldsea 100 Compilation of America's Most Successful Asian Entrepreneurs.

Compared to their population base, Asian Americans today are well represented in the professional sector and tend to earn higher wages. The Goldsea compilation of Notable Asian American Professionals show that many have come to occupy high positions at leading U.S. corporations, including a disproportionately large number as Chief Marketing Officers.

Asian Americans have made major contributions to the American economy. In 2012, there were just under 486,000 Asian American-owned businesses in the U.S., which together employed more than 3.6 million workers, generating $707.6 billion in total receipts and sales, with annual payrolls of $112 billion. In 2015, Asian American and Pacific Islander households had $455.6 billion in spending power (comparable to the annual revenue of Walmart) and made tax contributions of $184.0 billion.

Fashion designer and mogul Vera Wang, who is famous for designing dresses for high-profile celebrities, started a clothing company, named after herself, which now offers a broad range of luxury fashion products. An Wang founded Wang Laboratories in June 1951. Amar Bose founded the Bose Corporation in 1964. Charles Wang founded Computer Associates, later became its CEO and chairman. Two brothers, David Khym and Kenny Khym founded hip hop fashion giant Southpole in 1991. Jen-Hsun Huang co-founded the NVIDIA corporation in 1993. Jerry Yang co-founded Yahoo! Inc. in 1994 and became its CEO later. Andrea Jung serves as Chairman and CEO of Avon Products. Vinod Khosla was a founding CEO of Sun Microsystems and is a general partner of the prominent venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. Steve Chen and Jawed Karim were co-creators of YouTube, and were beneficiaries of Google's $1.65 billion acquisition of that company in 2006. Eric Yuan, founder of Zoom Video Communications, and Shahid Khan, owner of the Jacksonville Jaguars among others, are both in the U.S. top 100 in terms of net worth, according to Forbes. In addition to contributing greatly to other fields, Asian Americans have made considerable contributions in science and technology in the United States, in such prominent innovative R&D regions as Silicon Valley and The Triangle.

Government and politics

Asian Americans have a high level of political incorporation in terms of their actual voting population. Since 1907, Asian Americans have been active at the national level and have had multiple officeholders at local, state, and national levels. As more Asian Americans have been elected to public office, they have had a growing impact on foreign relations of the United States, immigration, international trade, and other topics. The first Asian American to be elected to the United States Congress was Dalip Singh Saund in 1957.

The highest ranked Asian American to serve in the United States Congress was Senator and President pro tempore Daniel Inouye, who died in office in 2012. There are several active Asian Americans in the United States Congress. With higher proportions and densities of Asian American populations, Hawaii has most consistently sent Asian Americans to the Senate, and Hawaii and California have most consistently sent Asian Americans to the House of Representatives.

The first Asian American member of the U.S. cabinet was Norman Mineta, who served as Secretary of Commerce and then Secretary of Transportation in the George W. Bush administration. As of 2021, the highest ranked Asian American by order of precedence is Vice President Kamala Harris. Previously, the highest ranked Asian American was Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao (2017-2021), who had also been in the order of precedence as U.S. Secretary of Labor (2001-2009).

There have been roughly "about a half-dozen viable Asian-American candidates" to ever run for president of the United States. Senator Hiram Fong of Hawaii, the child of Chinese immigrants, was a "favorite son" candidate at the Republican National Conventions of 1964 and 1968. In 1972, Representative Patsy T. Mink of Hawaii, a Japanese American, unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for president. Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, the son of Indian immigrants, unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination for president in 2016. Entrepreneur and nonprofit founder Andrew Yang, the son of Taiwanese immigrants, unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for president in 2020. In January 2021, Kamala Harris, the daughter of an Indian immigrant, became the first Asian American Vice President of the United States.

Voting behavior

Asian Americans were once a strong constituency for Republicans. In 1992, George H.W. Bush won 55% of Asian voters. However, by 2020, Asian Americans shifted to supporting Democrats, giving Joe Biden 70% support to Donald Trump's 29%. Ethnic background and country of origin have determined Asian American voting behavior in recent elections, with Indian Americans and to a lesser extent Chinese Americans being strong constituencies for Democrats, and Vietnamese Americans being a strong constituency for Republicans.

Journalism

Connie Chung was one of the first Asian American national correspondents for a major TV news network, reporting for CBS in 1971. She later co-anchored the CBS Evening News from 1993 to 1995, becoming the first Asian American national news anchor. At ABC, Ken Kashiwahara began reporting nationally in 1974. In 1989, Emil Guillermo, a Filipino American born reporter from San Francisco, became the first Asian American male to co-host a national news show when he was senior host at National Public Radio's All Things Considered. In 1990, Sheryl WuDunn, a foreign correspondent in the Beijing Bureau of The New York Times, became the first Asian American to win a Pulitzer Prize. Ann Curry joined NBC News as a reporter in 1990, later becoming prominently associated with The Today Show in 1997. Carol Lin is perhaps best known for being the first to break the news of 9-11 on CNN. Dr. Sanjay Gupta is currently CNN's chief health correspondent. Lisa Ling, a former co-host on The View, now provides special reports for CNN and The Oprah Winfrey Show, as well as hosting National Geographic Channel's Explorer. Fareed Zakaria, a naturalized Indian-born immigrant, is a prominent journalist and author specializing in international affairs. He is the editor-at-large of Time magazine, and the host of Fareed Zakaria GPS on CNN. Juju Chang, James Hatori, John Yang, Veronica De La Cruz, Michelle Malkin, Betty Nguyen, and Julie Chen have become familiar faces on television news. John Yang won a Peabody Award. Alex Tizon, a Seattle Times staff writer, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1997.

Military

Since the War of 1812, Asian Americans have served and fought on behalf of the United States. Serving in both segregated and non-segregated units until the desegregation of the US Military in 1948, 31 have been awarded the nation's highest award for combat valor, the Medal of Honor. Twenty-one of these were conferred upon members of the mostly Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team of World War II, the most highly decorated unit of its size in the history of the United States Armed Forces. The highest ranked Asian American military official was Secretary of Veteran Affairs, four-star general and Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki.

Science and technology

Asian Americans have made many notable contributions to Science and Technology.

Sports

Asian Americans have contributed to sports in the United States through much of the 20th century. Some of the most notable contributions include Olympic sports, but also in professional sports, particularly in the post-World War II years. As the Asian American population grew in the late 20th century, Asian American contributions expanded to more sports. Examples of female Asian American athletes include Michelle Kwan, Chloe Kim, Miki Gorman, Mirai Nagasu, and Maia Shibutani. Examples of male Asian American athletes include Jeremy Lin, Tiger Woods, Hines Ward, Richard Park, and Nathan Adrian.

Cultural influence

In recognition of the unique culture, traditions, and history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, the United States government has permanently designated the month of May to be Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. Asian American parenting as seen through relationships between Chinese parents and adolescence, which is described as being more authoritarian and less warm than relations between European parents and adolescence, has become a topic of study and discussion. These influences affect how parents regulate and monitor their children, and has been described as Tiger parenting, and has received interest and curiosity from non Chinese parents.

Health and medicine

| Country of origin |

Proportion of total in U.S. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IMGs | IDGs | INGs | |

| India | 19.9% (47,581) | 25.8% | 1.3% |

| Philippines | 8.8% (20,861) | 11.0% | 50.2% |

| Pakistan | 4.8% (11,330) | 2.9% |

|

| South Korea | 2.1% (4,982) | 3.2% | 1.0% |

| China | 2.0% (4,834) | 3.2% |

|

| Hong Kong |

|

|

1.2% |

| Israel |

|

|

1.0% |

Asian immigrants are also changing the American medical landscape through increasing number of Asian medical practitioners in the United States. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. government invited a number of foreign physicians particularly from India and the Philippines to address the shortage of physicians in rural and medically underserved urban areas. The trend in importing foreign medical practitioners, however, became a long-term solution as U.S. schools failed to produce enough health care providers to match the increasing population. Amid decreasing interest in medicine among American college students due to high educational costs and high rates of job dissatisfaction, loss of morale, stress, and lawsuits, Asian American immigrants maintained a supply of healthcare practitioners for millions of Americans. It is documented that Asian American international medical graduates including highly skilled guest workers using the J1 Visa program for medical workers, tend to serve in health professions shortage areas (HPSA) and specialties that are not filled by US medical graduates especially primary care and rural medicine. In 2020, of all the medical personnel in the United States, 17% of doctors were Asian Americans, 9% of physician assistants were Asian American, and more than 9% of nurses were Asian Americans.

Nearly one in four Asian Americans are likely to use common alternative medicine. This includes traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda. Due to the prevalence of usage, engaging with Asian American populations, through the practitioners of these common alternative medicines, can lead to an increase of usage of underused medical procedures.

Education

| Ethnicity | High school graduation rate, 2004 |

Bachelor's degree or higher, 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladeshis | not reported | 49.6% |

| Cambodian | not reported | 14.5% |

| Chinese | 80.8% | 51.8% |

| Filipinos | 90.8% | 48.1% |

| Indian | 90.2% | 70.7% |

| Indonesians | not reported | 48.7% |

| Japanese | 93.4% | 47.3% |

| Koreans | 90.2% | 52.9% |

| Laotians | not reported | 12.1% |

| Pakistanis | 87.4% | 55.1% |

| Taiwanese | not reported | 73.7% |

| Vietnamese | 70.0% | 26.3% |

| Total U.S. population | 83.9% | 27.9% |

Among America's major racial categories, Asian Americans have the highest educational qualifications. This varies, however, for individual ethnic groups. For example, a 2010 study of all Asian American adults found 42% have at least a college degree, but only 16% of Vietnamese Americans and only 5% for Laotians and Cambodians. It has been noted, however, that 2008 US Census statistics put the bachelor's degree attainment rate of Vietnamese Americans at 26%, which is not very different from the rate of 27% for all Americans. Census data from 2010 show 50% of Asian adults have earned at least a bachelor's degree, compared to 28% for all Americans, and 34% for non-Hispanic whites. Taiwanese Americans have some of the highest education rates, with nearly 74% having attained at least a bachelor's degree in 2010. as of December 2012 Asian Americans made up twelve to eighteen percent of the student population at Ivy League schools, larger than their share of the population. For example, the Harvard College Class of 2023 admitted students were 25% Asian American.

In the years immediately preceding 2012, 61% of Asian American adult immigrants have a bachelor or higher level college education.[70]

In August 2020, the U.S. Justice Department argued that Yale University discriminated against Asian candidates on the basis of their race, a charge the university denied.[158][159]

Popular Media

Asian American culture is referenced in a number of mainstream forms such as literature, tv shows, and movies. Crazy Rich Asians, directed by John M. Chu, follows Rachel Chu, a Chinese-American economics professor. Min Jin Lee's novel, Pachinko, is an intergenerational story that tells the story of Koreans who immigrate to Japan.

Social and political issues

Media portrayal

Because Asian Americans total about 7.2%[160] of the entire US population, diversity within the group is often overlooked in media treatment.[161][162]

Bamboo ceiling

This concept appears to elevate Asian Americans by portraying them as an elite group of successful, highly educated, intelligent, and wealthy individuals, but it can also be considered an overly narrow and overly one-dimensional portrayal of Asian Americans, leaving out other human qualities such as vocal leadership, negative emotions, risk taking, ability to learn from mistakes, and desire for creative expression.[163] Furthermore, Asian Americans who do not fit into the model minority mold can face challenges when people's expectations based on the model minority myth do not match with reality. Traits outside of the model minority mold can be seen as negative character flaws for Asian Americans despite those very same traits being positive for the general American majority (e.g., risk taking, confidence, empowered). For this reason, Asian Americans encounter a "bamboo ceiling", the Asian American equivalent of the glass ceiling in the workplace, with only 1.5% of Fortune 500 CEOs being Asians, a percentage smaller than their percentage of the total United States population.[164]

The bamboo ceiling is defined as a combination of individual, cultural, and organisational factors that impede Asian Americans' career progress inside organizations. Since then, a variety of sectors (including nonprofits, universities, the government) have discussed the impact of the ceiling as it relates to Asians and the challenges they face. As described by Anne Fisher, the "bamboo ceiling" refers to the processes and barriers that serve to exclude Asians and American people of Asian descent from executive positions on the basis of subjective factors such as "lack of leadership potential" and "lack of communication skills" that cannot actually be explained by job performance or qualifications.[165] Articles regarding the subject have been published in Crains, Fortune magazine, and The Atlantic.[166]

Illegal immigration

In 2012, there were 1.3 million Asian Americans; and for those awaiting visas, there were lengthy backlogs with over 450,000 Filipinos, over 325,000 Indians, over 250,000 Vietnamese, and over 225,000 Chinese awaiting visas. As of 2009, Filipinos and Indians accounted for the highest number of alien immigrants for "Asian Americans" with an estimated illegal population of 270,000 and 200,000 respectively. Indian Americans are also the fastest-growing alien immigrant group in the United States, with an increase in illegal immigration of 125% since 2000. This is followed by Koreans (200,000) and Chinese (120,000). Nonetheless, Asian Americans have the highest naturalization rates in the United States. In 2015, out of a total of 730,259 applicants, 261,374 became new Americans. According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, legal permanent residents or green card holders from India, Philippines, and China were among the top nationals applying for U.S. naturalization in 2015.

Due to the stereotype of Asian Americans being successful as a group and having the lowest crime rates in the United States, public attention to illegal immigration is mostly focused on those from Mexico and Latin America while leaving out Asians. Asians are the second largest racial/ethnic alien immigrant group in the U.S. behind Hispanics and Latinos. While the majority of Asian immigrants immigrate legally to the United States, up to 15% of Asian immigrants immigrate without legal documents.

Race-based violence

Asian Americans have been the targets of violence based on their race and or ethnicity. This violence includes, but is not limited to, such events as the Rock Springs massacre, Watsonville Riots, Bellingham Riots in 1916 against South Asians, attacks upon Japanese Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Korean American businesses targeted during the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Attacks on Chinese in the American frontier were common. This included the slaughter of forty to sixty Chinese miners by Paiute Indians in 1866, during the Snake War, the Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871, and an attack on Chinese miners at the Chinese Massacre Cove by cowboys in 1887 which resulted in 31 deaths. In the late 1980s, assaults and other hate crimes were committed against South Asians in New Jersey by a group of Latinos who were known as the Dotbusters. In the late 1990s, the lone death that occurred during the Los Angeles Jewish Community Center shooting by a white supremacist was a Filipino postal worker. On July 17, 1989, Patrick Edward Purdy, a drifter and former resident of Stockton, California, wen and opened fire on Cleveland Elementary School students in the playground who were mainly of southeast Asian descent. Within minutes, he fired dozens of rounds, although reports ranged. He was armed with two pistols and an AK-47 with a bayonet killing five students and shooting at least 37 others. After the shooting spree Purdy killed himself.

Even when it did not manifest as violence, contempt against Asian Americans was reflected in aspects of popular culture such as the playground chant "Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees".

After the September 11 attacks, Sikh Americans were targeted, becoming the victims of numerous hate crimes, including murder. Other Asian Americans have also been the victims of race-based violence in Brooklyn, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Bloomington, Indiana. Furthermore, it has been reported that young Asian Americans are more likely to be the targets of violence than their peers. In 2017, racist graffiti and other property damage was done to a community center in Stockton's Little Manila. Racism and discrimination still persist against Asian Americans, occurring not only against recent immigrants but also against well-educated and highly trained professionals.

Recent waves of immigration of Asian Americans to largely African American neighborhoods have led to cases of severe racial tension. Acts of large-scale violence against Asian American students by their black classmates have been reported in multiple cities. In October 2008, 30 black students chased and attacked 5 Asian students at South Philadelphia High School, and a similar attack on Asian students occurred at the same school one year later, prompting a protest by Asian students in response.

Asian-owned businesses have been a frequent target of tensions between black and Asian Americans. During the 1992 Los Angeles riots, more than 2000 Korean-owned businesses were looted or burned by groups of African Americans. From 1990 to 1991, a high-profile, racially motivated boycott of an Asian-owned shop in Brooklyn was organized by a local black nationalist activist, eventually resulting in the owner being forced to sell his business. Another racially motivated boycott against an Asian-owned business occurred in Dallas in 2012, after an Asian American clerk fatally shot an African American who had robbed his store. During the Ferguson unrest in 2014, Asian-owned businesses were looted, and Asian-owned stores were looted during the 2015 Baltimore protests while African American-owned stores were bypassed. Violence against Asian Americans continue to occur based on their race, with one source asserting that Asian Americans are the fastest-growing targets of hate crimes and violence.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, concern has grown due to an increase in anti-Asian sentiment in the United States. In March 2020, President Donald Trump called the disease "China Virus" and "Kung-Flu", based on its origin; in response organizations such as Asian Americans Advancing Justice and Western States Center, stated that doing so will increase anti-Asian sentiment and violence. Vox wrote that the Trump Administration's use of the terms "China Virus", "Kung-Flu", and "Wuhan virus" would lead to an increase in xenophobia. The disease naming controversy occurred at a time when the Chinese Foreign Ministry was claiming that the disease originated in the United States. Violent acts, relating to the disease, against Asian Americans have been documented mostly in New York, California, and elsewhere. As of December 31, 2020, there were 259 reports of anti-Asian incidents in New York reported to Stop AAPI Hate. As of March 2021, there have been more than 3800 anti-Asian racist incidents. A notable incident was the 2021 Atlanta spa shootings, a fatal attack in which six of the eight casualties were of Asian descent. The shooter reportedly said "I'm going to kill all Asians".

Racial stereotypes

Until the late 20th century, the term "Asian American" was mostly adopted by activists, while the average person who was of Asian ancestry identified with his or her specific ethnicity. The murder of Vincent Chin in 1982 was a pivotal civil rights case, and it marked the emergence of Asian Americans as a distinct group in United States.

Stereotypes of Asians have largely been collectively internalized by society and most of the repercussions of these stereotypes are negative for Asian Americans and Asian immigrants in daily interactions, current events, and governmental legislation. In many instances, media portrayals of East Asians often reflect a dominant Americentric perception rather than realistic and authentic depictions of true cultures, customs and behaviors. Asians have experienced discrimination and have been victims of hate crimes related to their ethnic stereotypes.

A study has indicated that most non-Asian Americans generally do not differentiate between Asian Americans who are of different ethnicities. Stereotypes of Chinese Americans and Asian Americans are nearly identical. A 2002 survey of Americans' attitudes toward Asian Americans and Chinese Americans indicated that 24% of the respondents disapprove of intermarriage with an Asian American, second only to African Americans; 23% would be uncomfortable supporting an Asian American presidential candidate, compared to 15% for an African American, 14% for a woman and 11% for a Jew; 17% would be upset if a substantial number of Asian Americans moved into their neighborhood; 25% had somewhat or very negative attitude toward Chinese Americans in general. The study did find several positive perceptions of Chinese Americans: strong family values (91%); honesty as business people (77%); high value on education (67%).

There is a widespread perception that Asian Americans are not "American" but are instead "perpetual foreigners". Asian Americans often report being asked the question, "Where are you really from?" by other Americans, regardless of how long they or their ancestors have lived in United States and been a part of its society. Many Asian Americans are themselves not immigrants but rather born in the United States. Many East Asian Americans are asked if they are Chinese or Japanese, an assumption based on major groups of past immigrants.

Discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans increased with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, according to a study done at Washington State University (WSU) and published in Stigma and Health. The NYPD reported a 1,900% increase in hate crimes motivated by anti-Asian sentiment in 2020, largely due to the virus origins in Wuhan, China.

According to a poll done in 2022, 33 percent of Americans believe Asian Americans are "more loyal to their country of origin" than the US while 21 percent falsely believe Asian Americans are at least "partially responsible" for the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, only 29 percent of Asian Americans believe they "completely agree" with the statement that they feel they belong and are accepted in the US, while 71 percent say they are discriminated in the US.

Model minority

Asian Americans are sometimes characterized as a model minority in the United States because many of their cultures encourage a strong work ethic, a respect for elders, a high degree of professional and academic success, a high valuation of family, education and religion. Statistics such as high household income and low incarceration rate, low rates of many diseases, and higher than average life expectancy are also discussed as positive aspects of Asian Americans.

The implicit advice is that the other minorities should stop protesting and emulate the Asian American work ethic and devotion to higher education. Some critics say the depiction replaces biological racism with cultural racism, and should be dropped. According to The Washington Post, "the idea that Asian Americans are distinct among minority groups and immune to the challenges faced by other people of color is a particularly sensitive issue for the community, which has recently fought to reclaim its place in social justice conversations with movements like #ModelMinorityMutiny."

The model minority concept can also affect Asians' public education. By comparison with other minorities, Asians often achieve higher test scores and grades compared to other Americans. Stereotyping Asian American as over-achievers can lead to harm if school officials or peers expect all to perform higher than average. The very high educational attainments of Asian Americans has often been noted; in 1980, for example, 74% of Chinese Americans, 62% of Japanese Americans, and 55% of Korean Americans aged 20–21 were in college, compared to only a third of the whites. The disparity at postgraduate levels is even greater, and the differential is especially notable in fields making heavy use of mathematics. By 2000, a plurality of undergraduates at such elite public California schools as UC Berkeley and UCLA, which are obligated by law to not consider race as a factor in admission, were Asian American. The pattern is rooted in the pre-World War II era. Native-born Chinese and Japanese Americans reached educational parity with majority whites in the early decades of the 20th century. One group of writers who discuss the "model minority" stereotype, have taken to attaching the term "myth" after "model minority", thus encouraging discourse regarding how the concept and stereotype is harmful to Asian American communities and ethnic groups.

The model minority concept can be emotionally damaging to some Asian Americans, particularly since they are expected to live up to those peers who fit the stereotype. Studies have shown that some Asian Americans suffer from higher rates of stress, depression, mental illnesses, and suicides in comparison to other groups, indicating that the pressures to achieve and live up to the model minority image may take a mental and psychological toll on some Asian Americans. The American Psychological Association has published a paper relying on 2007 data that takes issue with what is says are myths about the suicide rates of Asian Americans.

Alongside mental and psychological tolls that the model minority concept has on Asian Americans, they are also faced with the repercussions that it has on physical health and the desire for individuals to seek medical care more specifically cancer screening or treatment. Asian Americans, between the other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, are the only group with the leading cause of death being cancer while having significantly low rates of cancer screenings. Different pressures like alienation if diagnosed or the desire to conform to stereotypes of the image of a healthy lifestyle can deter individuals from seeking cancer screenings or treatment before the onset of symptoms.

The "model minority" stereotype fails to distinguish between different ethnic groups with different histories. When divided up by ethnicity, it can be seen that the economic and academic successes supposedly enjoyed by Asian Americans are concentrated into a few ethnic groups. Cambodians, Hmong, and Laotians (and to a lesser extent, Vietnamese) all have relatively low achievement rates, possibly due to their refugee status, and the fact that they are non-voluntary immigrants.

Social and economic disparities

In 2015, Asian American earnings were found to exceed all other racial groups when all Asian ethnic groups are grouped as a whole. Yet, a 2014 report from the Census Bureau reported that 12% of Asian Americans were living below the poverty line, while 10.1% of non-Hispanic White Americans live below the poverty line. A 2017 study of wealth inequality within Asian Americans found a greater gap between wealthy and non-wealthy Asian Americans compared to non-Hispanic white Americans. Once country of birth and other demographic factors are taken into account, a portion of the sub-groups that make up Asian Americans are much more likely than non-Hispanic White Americans to live in poverty.

There are major disparities that exist among Asian Americans when specific ethnic groups are examined. For example, in 2012, Asian Americans had the highest educational attainment level of any racial demographic in the country. Yet, there are many sub groups of Asian Americans who suffer in terms of education with some sub groups showing a high rate of dropping out of school or lacking a college education. This occurs in terms of household income as well – in 2008 Asian Americans had the highest median household income overall of any racial demographic, while there were Asian sub-groups who had average median incomes lower than both the U.S. average and non-Hispanic Whites. In 2014, data released by the United States Census Bureau revealed that five Asian American ethnic groups are in the top ten lowest earning ethnicities in terms of per capita income in all of the United States.

The Asian American groups that have low educational attainment and high rates of poverty both in average individual and median income are Bhutanese Americans, Bangladeshi Americans, Cambodian Americans, Burmese Americans, Nepali Americans, Hmong Americans, and Laotian Americans. This affects Vietnamese Americans as well, albeit to a lesser degree, as early 21st-century immigration from Vietnam are almost entirely not from refugee backgrounds. These individual ethnicities experience social issues within their communities, some specific to their individual communities themselves. Issues such as suicide, crime, and mental illness. Other issues experienced include deportation, and poor physical health. Within the Bhutanese American community, it has been documented that there are issues of suicide greater than the world's average. Cambodian Americans, some of whom immigrated as refugees, are subject to deportation. Crime and gang violence are common social issues among Asian Americans of refugee backgrounds such as Cambodian, Laotian, Hmong, and Vietnamese Americans.