| Great Salt Lake | |

|---|---|

| Ti'tsa-pa (Shoshoni) | |

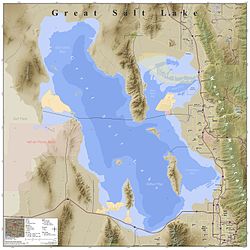

Satellite photo from August 2018 after years of drought,

reaching near-record lows. Note the difference in colors between the

northern and southern portions of the lake, the result of a railroad causeway. | |

| Location | Utah, United States |

| Coordinates | 41°10′N 112°32′W |

| Type | Endorheic lake, hypersaline lake |

| Primary inflows | Bear, Jordan, Weber Rivers |

| Catchment area | 21,500 sq mi (56,000 km2) |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 75 mi (121 km) |

| Max. width | 28 mi (45 km) |

| Surface area | 950 sq mi (2,500 km2) as of 2021 |

| Average depth | 16 ft (4.9 m), when lake is at average level |

| Max. depth | 33 ft (10 m) average, high of 45 ft (14 m) in 1987, low of 24 ft (7.3 m) in 2021 |

| Water volume | 15,338,693.6 acre⋅ft (18.92 km3) |

| Surface elevation | historical average of 4,200 feet (1,300 m), 4,190.5 feet (1,277.3 m) as of 2022 March 14 |

| Islands | 8–15 (variable, see Islands) |

| Settlements | Salt Lake City and Ogden |

The Great Salt Lake (Shoshone: Ti'tsa-pa “Bad Water”) is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. It lies in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah and has a substantial impact upon the local climate, particularly through lake-effect snow. It is a remnant of Lake Bonneville, a prehistoric body of water that covered much of western Utah.

The area of the lake can fluctuate substantially due to its low average depth of 16 feet (4.9 m). In the 1980s, it reached a historic high of 3,300 square miles (8,500 km2), and the West Desert Pumping Project was established to mitigate flooding by pumping water from the lake into the nearby desert. In 2021, after years of sustained drought and increased water diversion upstream of the lake, it fell to its lowest recorded area at 950 square miles (2,500 km2), falling below the previous low set in 1963. Continued shrinkage could turn the lake into a bowl of toxic dust, poisoning the air around Salt Lake City.

The lake's three major tributaries, the Jordan, Weber, and Bear rivers together deposit around 1.1 million tons of minerals in the lake per year. Since the lake has no outlet besides evaporation, these minerals accumulate and give the lake high salinity (far saltier than seawater) and density. This density causes swimming in the lake to feel similar to floating.

The lake has been called "America's Dead Sea" and provides a habitat for millions of native birds, brine shrimp, shorebirds, and waterfowl, including the largest staging population of Wilson's phalarope in the world.

Origin

The Great Salt Lake is a remnant of a much larger prehistoric lake called Lake Bonneville. At its greatest extent, Lake Bonneville spanned 22,400 square miles (58,000 km2), nearly as large as present-day Lake Michigan, and roughly ten times the area of the Great Salt Lake today. Bonneville reached 923 ft (281 m) at its deepest point and covered much of present-day Utah and small portions of Idaho and Nevada during the ice ages of the Pleistocene Epoch.

Lake Bonneville existed until about 16,800 years ago, when a large portion of the lake was released through the Red Rock Pass in Idaho, resulting in cataclysmic floods. With the warming climate, the remaining lake began to dry, leaving the Great Salt Lake, Utah Lake, Sevier Lake, and Rush Lake behind.

History

The Shoshone, Ute, and Paiute have lived near the Great Salt Lake for thousands of years. At the time of Salt Lake City's founding, the valley was within the territory of the Northwestern Shoshone; however, occupation was seasonal, near streams emptying from canyons into the Salt Lake Valley. One of the local Shoshone tribes, the Western Goshute tribe, referred to the lake as Pi'a-pa, meaning "big water", or Ti'tsa-pa, meaning "bad water".

There are several maps dating back to 1575 that show the Great Salt Lake at the correct latitude and longitude, within an accuracy of a few degrees. One example is a map by Nicolas Sanson dated 1650. The Great Salt Lake entered written history through the records of Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, who learned of its existence from the Timpanogos Utes in 1776. No European name was given to it at the time, and it was not shown on the map by Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, the cartographer for the expedition. Escalante had been on the shores of Utah Lake, which he named Laguna Timpanogos. It was the larger of the two lakes that appeared on Miera's map. Other cartographers followed his lead and charted Lake Timpanogos as the largest (or larger) lake in the region. As people became aware of the Great Salt Lake, they interpreted the maps to think that "Timpanogos" referred to the Great Salt Lake. On some maps, the two names were used synonymously. In time, "Timpanogos" was dropped from the maps and its original association with Utah Lake was forgotten.

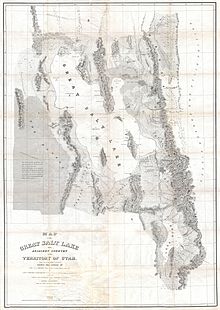

In 1824, it was observed, apparently independently, by Jim Bridger and Etienne Provost. Shortly thereafter, other trappers saw it and walked around it. Most of the trappers, however, were illiterate and did not record their discoveries. As oral reports of their findings made their way to those who did make records, some errors were made. In 1843, John C. Fremont led the first scientific expedition to the lake, but with winter coming on, he did not take the time to survey the entire lake. That happened in 1850 under the leadership of Howard Stansbury (Stansbury discovered and named the Stansbury mountain range and Stansbury island). John Fremont's overly glowing reports of the area were published shortly after his expedition. Stansbury also published a formal report of his survey work which became very popular. His report of the area included a discussion of Mormon religious practices based on Stansbury's interaction with the Mormon community in Great Salt Lake City, which had been established three years earlier in 1847.

Beginning in November 1895, artist and author Alfred Lambourne spent 4 months living on the remote Gunnison Island, where he wrote a book of musing and poetry, Our Inland Sea. From November 1895 to March 1896, he was alone. In March, a few guano sifters arrived to harvest and sell the guano of the nesting birds as fertilizer. Lambourne included musings about these guano sifters in his work. Lambourne left the island early in the winter of 1896 along with the first group of guano sifters.

1930s Fresh Water Project

In the early 1930s, there was a project to dam off a third of the lake with dikes on the east side north of Salt Lake City to make a freshwater reservoir for drinking and irrigation. The project was abandoned before it got beyond the planning stage.

Causeway

The causeway across the lake was built in the 1950s by the Morrison-Knudsen construction company for the Southern Pacific Railroad as a replacement to a previously built wooden trestle, which was the major component of the Lucin Cutoff. The route is now owned and operated by Union Pacific. About 15 trains cross the 20 mi (32 km) causeway each day. Prior to December 2, 2016, the causeway constrained the flow of water between northern and southern arms, which has a significant impact on various industries surrounding the lake. The construction of a 180-foot-long (55 m) bridge created an opening of the causeway for water to flow between the arms of the lake.

Willard Bay Reservoir

Willard Bay, also known as Willard Bay Reservoir or Arthur V. Watkins Reservoir is a freshwater reservoir completed in 1964, which separated, drained, and subsequently filled with fresh water from the Weber River a portion of the Great Salt Lake's northeastern arm.

West Desert Pumping Project

Record high water levels in the 1980s caused a large amount of property damage for owners on the eastern side of the Great Salt Lake, and the water started to erode the base of Interstate 80. In response, the State of Utah built the West Desert Pumping Project on the western side of the lake. It began operation on April 10, 1987. This project consists of a pumping station (41°15′9.28″N 113°4′53.31″W) at Hogup Ridge, containing three pumps with a combined capacity of moving 1,500,000 US gallons per minute (95 m3/s), an inlet canal, and an outlet canal. Also, there are 25 miles (40 km) of dikes and a 10-mile (16 km) access road between the town of Lakeside and the pumping station.

This pumping project was designed to increase the surface area of the Great Salt Lake and thus increase the rate of water evaporation. The pumps drove some of the water of the Great Salt Lake into the 320,000-acre (1300-square kilometer) Newfoundland Evaporation Basin in the desert west of the lake. A weir in the dike at the southern end of the Newfoundland Mountains regulated the level of water in the basin and it sometimes returned salty water from the evaporation basin into the main body of the Great Salt Lake.

At the end of their first year of operation, the pumps had removed about 500,000 acre-feet (620,000,000 m3) of water from the Great Salt Lake. The project was shut down in June 1989, as the level of the lake had dropped by nearly six feet (1.8 meters) since reaching its peak levels during June 1986 and March 1987. The Utah Division of Water Resources credits the project with "over one-third of that decline". In total, the pumps removed 2,730,000 acre-feet (3.37 km3) of water while they operated.

Although the pumps are no longer in use, they have been kept in place in case the level of the Great Salt Lake ever rises that high again.

Shrinking

Drought conditions, climate change, and the overuse of snowmelt have caused the Great Salt Lake to shrink considerably. As of July 2022 the Great Salt Lake occupies some 950 square miles. In 1987, it occupied some 3300 square miles. As of March 2023, the lake's highest recorded surface elevation was 4,211.2 feet on April 15, 1987; the lowest recorded surface elevation was 4,188.5 feet on December 17, 2022. In 2023, it was estimated that without policy changes, the lake would dry up in 2028, with local species killed off by overly salty water somewhat before that.

Geography

The Great Salt Lake lends its name to Salt Lake City, originally named "Great Salt Lake City" by the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), Brigham Young, who led a group of Mormon pioneers to the Salt Lake Valley southeast of the lake on July 24, 1847.

The lake lies in parts of five counties: Box Elder, Davis, Tooele, Weber, and Salt Lake. Salt Lake City and its suburbs are located to the south-east and east of the lake, between the lake and the Wasatch Mountains, but land around the north and west shores is almost uninhabited. The Bonneville Salt Flats are to the west, and the Oquirrh and Stansbury Mountains rise to the south.

The Great Salt Lake is fed by three major rivers and several minor streams. The three major rivers are each fed directly or indirectly from the Uinta Mountain range in northeastern Utah. The Bear River starts on the north slope of the Uintas and flows north past Bear Lake, into which some of Bear River's waters have been diverted via a man-made canal into the lake, but later empty back into the river by means of the Bear Lake Outlet. The river then turns south in southern Idaho and eventually flows into the northeast arm of the Great Salt Lake. The Weber River also starts on the north slope of the Uinta Mountains and flows into the east edge of the lake. The Jordan River does not receive its water directly from the Uintas; rather, it flows from freshwater Utah Lake, which itself is fed primarily by the Provo River. The Provo River does originate in the Uintas, a few miles from the Weber and Bear. The Jordan flows from the north part of Utah Lake into the south-east corner of the Great Salt Lake.

Due to the lake's shallowness, the water level can fall and rise dramatically during dry years or high-precipitation years, thereby reflecting prolonged drought or wet periods. The change in the level of lake level is strongly modulated by the Pacific Ocean through atmospheric circulations that fluctuate at low frequency. By capturing these climate oscillations while using tree-ring reconstruction of lake level, scientists can predict the lake level fluctuation onward for 5–8 years. The Utah Climate Center provides prediction of the Great Salt Lake's annual lake level. This forecast uses central tropical Pacific Ocean temperature, watershed precipitation, tree-ring data of 750+ years, and the lake level itself.

A railroad line – the Lucin Cutoff – runs across the lake, crossing the southern end of Promontory Peninsula. The mostly solid causeway supporting the railway divides the lake into three portions: the north-east arm, north-west arm, and southern. The causeway obstructed the normal mixing of the waters of the lake, because there were only three 100-foot (30 m) breaches. Because no rivers, except a few minor streams, flow directly into the north-west arm, Gunnison Bay, it is substantially saltier than the rest of the lake. This saltier environment promotes different types of algae from those growing in the southern part of the lake, leading to a marked color difference on the two sides of the causeway. On December 1, 2016, the opening of a new 180-foot-long (55 m) bridge allowed water to flow from the southern arm of the lake into the north-west arm. At the time of opening of the causeway, the north-west arm was nearly 3 feet (90 cm) lower than the southern arm. By April 2017, the levels of both arms of the lake had risen due to spring runoff, and the north-western arm was within 1 foot (30 cm) of the southern arm.

Islands

Categorically stating the number of islands is difficult, as the method used to determine what is an island is not necessarily the same in each source. Since the water level of the lake can vary greatly between years, what may be considered an island in a high water year may be considered a peninsula in another, or an island in a low water year may be covered during another year. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior and the U.S. Geological Survey, "there are eight named islands in the lake that have never been totally submerged during historic time. All have been connected to the mainland by exposed shoals during periods of low water." In addition to these eight islands, the lake also contains a number of rocks, reefs, or shoals that become fully or partially submerged at high water levels.

The Utah Geological Survey, on the other hand, states "the lake contains 11 recognized islands, although this number varies depending on the level of the lake. Seven islands are in the southern portion of the lake and four in the northwestern portion."

The size and whether they are counted as islands during any particular year depends mostly on the level of the lake. From largest to smallest, they are Antelope Island, Stansbury Island, Fremont Island, Carrington Island, Dolphin Island, Cub Island, and Badger Island, and various rocks, reefs, or shoals with names like Strongs Knob, Gunnison Island, Goose, Browns, Hat (Bird), Egg Island, Black Rock, and White Rock. Dolphin Island, Cub Island, and Strongs Knob are in the northwestern arm. The rest are in the southern portion of the Great Salt Lake.

Black Rock, Antelope Island, White Rock, Egg Island, Fremont Island, and the Promontory mountain range are each extensions of the Oquirrh Mountain Range, which dips beneath the lake at its southeastern shore. Stansbury, Carrington, and Hat Islands are extensions of the Stansbury mountain range, and Strongs Knob is an extension of the Lakeside Mountains which run along the lake's western shore. The lake is deepest in the area between these island chains, measured by Howard Stansbury in 1850 at about 35 feet (11 meters) deep, and an average depth of 13 feet (four meters). When the water levels are low, Antelope Island becomes connected to the shore as a peninsula, as do Goose Islands, Browns Island, and some of the other islands. Stansbury Island and Strongs Knob remain peninsulas unless the water level rises well-above the average.

Lake-effect precipitation

Due to the warm waters of the Great Salt Lake, lake-effect snowfalls are frequent phenomena in the surrounding area. Cold north, north-west, or west winds generally blow across the lake following the passage of a cold front, and the temperature difference between the warm lake and the cool air can form clouds that lead to precipitation downwind of the lake. It is typically heaviest in Tooele County to the east, and north into central Davis County, and can deposit excessive snowfall amounts, generally within a narrow band which is highly-dependent on the direction the wind is blowing.

The lake-effect snowfalls are more likely to occur in late fall, early winter and spring, due to the higher temperature differences between the lake and the air above it. During summer, the temperature differences can cause thunderstorms to form over the lake and drift eastward along the northern Wasatch Front. Some rainstorms may also be partially attributed to the lake effect in fall and spring. It is estimated that approximately six to eight lake effect snowstorms occur in a year, and that 10% of the average precipitation of Salt Lake City can be attributed to the lake effect.

Hydrology

Because of its high salt concentration, the lake water is unusually dense, and most people can float more easily than in other bodies of water, particularly in Gunnison Bay, the saltier north arm of the lake.

Water levels have been recorded since 1875, averaging about 4,200 feet (1,300 m) above sea level. Since the Great Salt Lake is a shallow lake with gently sloping shores around all edges except on the south side, small variations in the water level greatly affect the extent of the shoreline. The water level can rise dramatically in wet years and fall during dry years. The water level is also affected by the amount of water flow diverted for agricultural and urban uses. The Jordan and Weber rivers, in particular, are diverted for other uses. In the 1880s, Grove Karl Gilbert predicted that the lake – then in the middle of many years of recession – would virtually disappear except for a small remnant between the islands.

A 2014 study used tree rings collected in the watershed of the Great Salt Lake to create a 576-year record of lake level reconstruction. The lake level change is strongly modulated by Pacific Ocean-coupled ocean/atmospheric oscillations at low frequency and therefore reflects the decadal-scale wet/dry cycles that characterize the region. By capturing these climate oscillations as well as utilizing the tree-ring reconstruction of lake level change, researchers were able to predict the lake level fluctuation onward for as long as 5–8 years.

The Great Salt Lake differs in elevation between the south and north parts. The causeway for the Lucin Cutoff divides the lake into two parts. The water-surface elevation of the south part of the lake is usually 0.5 to 2 feet (15–61 cm) higher than that of the north part because most of the inflow to the lake occurs from the south.

Salinity

Most of the salts dissolved in the lake and deposited in the desert flats around it reflect the concentration of solutes by evaporation; Lake Bonneville itself was fresh enough to support populations of fish. More salt is added yearly via rivers and streams, though the amount is much less than the relict salt from Bonneville.

The salinity of the lake's main basin, Gilbert Bay, is highly variable and depends on the lake's level; it ranges from 5 to 27% (50 to 270 parts per thousand). For comparison, the average salinity of the world ocean is 3.5% (35 parts per thousand) and 33.7% in the Dead Sea. The ionic composition is similar to seawater, much more so than the Dead Sea's water; compared to the ocean, the Great Salt Lake's waters are slightly enriched in potassium and depleted in calcium. Dissolved ions do not necessarily increase or decrease in step with changes of total dissolved solids. For example, in October 1903, dissolved solids tallied 27.72% and by February 1910 they were down to 17.68%, with chlorine, sodium and sulfate levels substantially lower, but over the same time calcium, magnesium and potassium increased, with the increase of magnesium especially pronounced.

Ecosystem

The high salinity in parts of the lake makes them uninhabitable for all but a few species, including brine shrimp, brine flies, and several forms of algae. The brine flies have an estimated population of over one hundred billion and serve as the main source of food for many of the birds which migrate to the lake. However, the fresh- and salt-water wetlands along the eastern and northern edges of the Great Salt Lake provide critical habitat for millions of migratory shorebirds and waterfowl in western North America. These marshes account for approximately 75% of the wetlands in Utah. Some of the birds that depend on these marshes include: Wilson's phalarope, red-necked phalarope, American avocet, black-necked stilt, marbled godwit, snowy plover, western sandpiper, long-billed dowitcher, tundra swan, American white pelican, white-faced ibis, California gull, eared grebe, peregrine falcon, bald eagle, plus large populations of various ducks and geese.

There are twenty-seven private duck clubs, seven state waterfowl management areas, and a large federal bird refuge on the Great Salt Lake's shores. Wetland/wildlife management areas include the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge; Gillmor Sanctuary; Great Salt Lake Shore lands Preserve; Salt Creek, Public Shooting Grounds, Harold Crane, Locomotive Springs, Ogden Bay, Timpie Springs, and Farmington Bay Waterfowl Management Areas.

Several islands in the lake provide critical nesting areas for various birds. Access to Hat, Gunnison, and Cub islands is strictly limited by the State of Utah in an effort to protect nesting colonies of American white pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos). The islands within the Great Salt Lake also provide habitat for lizard and mammalian wildlife and a variety of plant species. Some species may have been extirpated from the islands. For example, a number of explorers who visited the area in the mid-1800s (e.g. Emmanuel Domenech, Howard Stansbury, Jules Rémy) noted an abundance of yellow-flowered "onions" on several of the islands, which they identified as Calochortus luteus. This species today occurs only in California; however, at that time the name C. luteus was applied to plants that later were named C. nuttallii. A yellow-flowered Calochortus was first named as a variety of C. nuttallii but was later separated into a new species, C. aureus. This species occurs in Utah today, though apparently no longer on the islands of the Great Salt Lake.

Because of the Great Salt Lake's high salinity, it has few fish, but they do occur in Bear River Bay and Farmington Bay when spring runoff brings fresh water into the lake. A few aquatic animals live in the lake's main basin, including centimeter-long brine shrimp (Artemia franciscana). Their tiny, hard-walled eggs or cysts (diameter about 200 micrometers) are harvested in quantity during the fall and early winter. They are fed to prawns in Asia, sold as novelty "Sea-Monkeys," sold either live or dehydrated in pet stores as a fish food, and used in testing of toxins, drugs, and other chemicals. There are also two species of brine fly, as well as protozoa, rotifers, bacteria and algae.

Salinity differences between the sections of the lake separated by the railroad causeway result in significantly different biota. A phytoplankton community dominated by green algae or cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) tint the water south of the causeway a greenish color. North of the causeway, the lake is dominated by Dunaliella salina, a species of algae which releases beta-carotene, and the bacteria-like haloarchaea, which together give the water an unusual reddish or purplish color. The dense, high-salinity water of the North Arm flows back through the causeway into the Southern portion of the lake, creating a deep brine layer there.

Although brine shrimp can be found in the arm of the lake north of the causeway, studies conducted by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources indicate that these are likely transient. Populations of brine shrimp are mostly restricted to the lake's south arm.

In the two bays that receive most of the lake's freshwater inflows, Bear River Bay and Farmington Bay, the diversity of organisms is much higher. Salinities in these bays can approach that of fresh water when the spring snow melt occurs, and this allows a variety of bacteria, algae and invertebrates to proliferate in the nutrient-rich water. The abundance of invertebrates such as gnat larvae (chironomids) and back swimmers (Trichocorixa) are fed upon extensively by the huge shorebird and waterfowl populations that utilize the lake. Fish in these bays are fed upon by diving terns and pelicans.

Pink Floyd the flamingo

A solitary Chilean flamingo, named Pink Floyd after the English rock band, wintered at the Great Salt Lake. He escaped from Salt Lake City's Tracy Aviary in 1987 and lived in the wild, eating brine shrimp and socializing with gulls and swans. A group of Utah residents suggested petitioning the state to release more flamingos in an effort to keep Floyd company and as a possible tourist attraction. Pink Floyd was last seen in Idaho, in the area of Camas National Wildlife Refuge in 2005.

Elevated mercury levels

During a survey in the mid-1990s, U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service researchers discovered a high level of methylmercury in the Great Salt Lake with 25 nanograms per liter of water. For comparison, a fish consumption advisory was issued at the Florida Everglades after water there was found to contain 1 nanogram per liter. The extremely high methylmercury concentrations have been only in the lake's anoxic deep brine layer (monimolimnion) below a depth of 20 feet (6.1 m), but concentrations are also moderately high up in the water column where there is oxygen to support brine shrimp and brine flies.

The toxic metal shows up throughout the lake's food chain, from brine shrimp to eared grebes and cinnamon teal.

The finding of high mercury levels prompted further studies, and a health advisory warning hunters not to eat common goldeneye or northern shoveler, two species of duck found in the lake. It has been stated that this does not pose a risk to other recreational users of the lake.

After later studies were conducted with a larger number of birds, the advisories were revised and another was added for cinnamon teal. Seven other species of duck were studied and found to have levels of mercury below EPA guidelines, thus being determined safe to eat.

A study in 2010 suggested that the main source of the mercury is from atmospheric deposition from worldwide industry, rather than local sources. As water levels rise and fall, mercury accumulation does as well. About 16% of the mercury is from rivers, and 84% is from the atmosphere as an inorganic form, which is converted into more toxic methyl mercury by bacteria which thrive in the more saline water of the North arm affected by the causeway. A 2020 study found high concentrations of mercury in the lake's sediments, a consequence from smelting and mining activities in the surrounding mountains. The mercury and other metals can contaminate the overlying water, and in turn, move into brine shrimp and other organisms.

Commerce

Great Salt Lake contributes an estimated $1.3 billion annually to Utah's economy, including $1.1 billion from industry (primarily mineral extraction), $136 million from recreation, and $57 million from the harvest of brine shrimp.

Solar evaporation ponds at the edges of the lake produce salts and brine (water with high salt quantity). Minerals extracted from the lake include: sodium chloride (common salt), used in water softeners, salt lick blocks for livestock, and to melt ice on local roadways (food-grade salt is not produced from the lake, as it would require costly processing to ensure its purity); potassium sulfate, used as a commercial fertilizer; and magnesium-chloride brine, used in the production of magnesium metal, chlorine gas, and as a dust suppressant. US Magnesium operates a plant on the southwest shore of the lake, which produces 14% of the worldwide supply of magnesium, more than any other North American magnesium operation. Mineral-extraction companies operating on the lake pay royalties on their products to the State of Utah, which owns the lake.

Brine shrimp

The harvest of brine shrimp cysts during fall and early winter has developed into a significant local industry, with the lake providing 35% to 45% of the worldwide supply of brine shrimp, and cysts selling for as high as $35 per pound ($77/kg). Brine shrimp were first harvested during the 1950s and sold as commercial fish food. In the 1970s, the focus changed to their eggs, known as cysts, which were sold primarily outside the US as food for shrimp, prawns, and some fish. Today, these are mostly sold in East Asia and South America. The amount of cysts and the quality are affected by several factors, but salinity is most important. The cysts will hatch at 2 to 3% salinity, but the greatest productivity is at salinities above about 10%. If the salinity drops near 5% to 6%, the cysts will lose buoyancy and sink, making them more difficult to harvest.

The causeway across the lake was built in the 1950s as a replacement to a wooden trestle. Prior to December 2, 2016, the causeway constrained the flow of water between northern and southern arms, which has a significant impact on various industries surrounding the lake. The construction of a 180-foot-long (55 m) bridge created an opening of the causeway for water to flow between the arms of the lake.

The northern arm of the lake has a much higher salinity, to the point that the native brine shrimp cannot survive in its waters. In the southern portion of the lake, where the vast majority of the fresh water inlets are found, the salt level can dip below what is necessary for the brine shrimp to survive. With the opening of the bridge, the salinity of the northern arm of the lake will likely drop as less saline water from the southern arm of the lake flows into the northern arm. The brine shrimp harvesting industry could benefit from the freer flow of water. There were concerns from the brine shrimp harvesting industry that the conditions in the southern arm of the lake were becoming too saline for the brine shrimp, following several years of lower precipitation in the lake's watershed. The precipitation in the watershed was above normal for the water year beginning on October 1, 2016. The additional water allowed the levels of both arms of the lake to rise, creating better conditions for a healthy brine shrimp population.

Oil and minerals

Great Salt Lake Minerals Company (a subsidiary of Compass Minerals) extracts minerals from the northern bay. The company potentially benefited from the higher salinity of the north-west arm of the lake but had difficulty accessing water from the lake because of lower water level. Prior to the opening of the causeway, the intake channels had to be extended to reach the water.

Morton Salt, Cargill Salt, Broken Arrow Salt and the Renco Group's U.S. Magnesium each extract minerals from the southern bay and could benefit from a more natural mixture of water between the two sides of the lake.

The lake's north arm contains deposits of oil, but it is of poor quality and it is not economically feasible to extract and purify it. As of 1993, approximately 3,000 barrels (480 m3) of crude oil had been produced from shallow wells along the shore. The oil field at Rozel Point produced an estimated 10,000 barrels (1,600 m3) of oil from 30 to 50 wells, but has been inactive since the mid-1980s. Oil seeps in the area had been known since the late 19th century, and attempts at production began in 1904. Industrial debris from this field remained in place near Spiral Jetty until a cleanup effort by the Division of Oil, Gas and Mining and the Division of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands was completed in December 2005.

Recreation

The lake is one of Utah's largest tourist attractions. Antelope Island State Park is a popular tourist destination that offers panoramic views of the lake, hiking and biking trails, wildlife viewing and access to beaches.

The State of Utah operates a marina on the south shore of the lake at Great Salt Lake State Park and another in Antelope Island State Park. With its sudden storms and expansive spread, the lake is a great test of sailing skills. Single mast, simple sloops are the most popular boats. Sudden storms and lack of experience on the part of boaters are the two most dangerous elements in boating and sailing on the Great Salt Lake.

Dramatically fluctuating lake levels have inhibited the creation and success of tourist-related developments. There is also a problem with pollution from industrial and urban effluent, as well as a natural "lake stink" caused by the decay of insects and other wildlife, particularly during times of low water.

Saltair

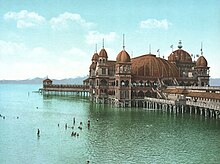

Three resorts have operated under the name Saltair on the southern shore of the lake since 1893. Rising and lowering water levels have affected each iteration.

The first Saltair pavilion was destroyed by fire on April 22, 1925. A new pavilion was built and the resort was expanded at the same location by new investors, but after being closed for several years, it was destroyed by arson in 1970. The second Saltair included a fun house and a dancing venue.

The current Saltair serves as a concert venue. The new resort was completed in 1981, approximately a mile (1600 m) west of the original.

Garfield Beach Resort

The Garfield Beach Resort was established by Captain Thomas Douris in 1881 and was originally called Garfield Landing. The resort was located near Black Rock outside of the town of Corinne, and patrons traveled to it via the steamboat General Garfield. After the expansion of the resort, the General Garfield was replaced by two steamers, the Susie Riter and the Whirlwind. The iconic General Garfield was moored to the dock as a landmark. The main attraction of the resort was a massive pavilion 400 feet from shore. It covered 165 by 400 feet (50 by 122 m) and included 300 feet (91 m) of covered deck. The success of Garfield Beach eventually overtook the neighboring Black Rock resort. In 1887, the resort was purchased by the Utah and Nevada railroad. They improved the site by adding an array of bathhouses, a restaurant, and other amenities, including a bowling alley. The resort was the Salt Lake's first to have an electric generator, which powered its many concerts, and parties held atop the pavilion tower. Garfield Beach was the most popular Salt Lake resort until Saltair was built in 1893. The resort was put out of service by a fire in 1904.

Arts and culture

- Spiral Jetty

- The northwest arm of the lake, near Rozel Point, is the location for Robert Smithson's work of land art, Spiral Jetty (1970), which is only visible when the level of Great Salt Lake drops below 4,197.8 feet (1,279.5 m) above sea level.

- Oolitic sand

- The lake and its shores contain oolitic sand, small, rounded, or spherical grains of sand that are made up of a nucleus (generally a small mineral grain) and concentric layers of calcium carbonate (lime) and look similar to very small pearls.

- Whales in the Great Salt Lake

- Local legend maintains that in 1875, entrepreneur James Wickham had two whales released into the Great Salt Lake, with the intent of using them as a tourist attraction. The whales are said to have disappeared into the lake and been subsequently sighted multiple times over a number of months, but there have never been any confirmed sightings of the whales since the time of their supposed release. Scientists believe they could not have survived due to the high salinity of the lake.

- Lake monster

- In mid-1877, J. H. McNeil was with many other Barnes and Co. Salt Works employees on the lake's north shore in the evening. They claimed to have seen a large monster with a body like a crocodile and a horse’s head in the lake. They claimed this monster attacked the men, who quickly ran away and hid until morning. This creature is regarded by some to have simply been a buffalo in the lake. Thirty years prior, "Brother Bainbridge" claimed to have sighted a creature that looked like a dolphin in the lake near Antelope Island. This monster is called by some the North Shore Monster.