Gender digital divide is defined as gender biases coded into technology products, technology sector and digital skills education.

Background

Education systems are increasingly trying to ensure equitable, inclusive and high-quality digital skills education and training. Though digital skills open pathways to further learning and skills development, women and girls are still being left behind in digital skills education. Globally, digital skills gender gaps are growing, despite at least a decade of national and international efforts to close them. The economic and political interests of its indicators have also been questioned.

Digital skills gap

Women are less likely to know how to operate a smartphone, navigate the internet, use social media and understand how to safeguard information in digital mediums (abilities that underlie life and work tasks and are relevant to people of all ages) worldwide. There is a gap from the lowest skill proficiency levels, such as using apps on a mobile phone, to the most advanced skills like coding computer software to support the analysis of large data sets.

Women in numerous countries are 25% less likely than men to know how to leverage ICT for basic purposes, such as using simple arithmetic formulas in a spreadsheet. UNESCO estimates that men are around four times more likely than women to have advanced ICT skills such as the ability to programme computers. Across G20 countries 7% of ICT patents are generated by women, and the global average is at 2%. Recruiters for technology companies in Silicon Valley estimate that the applicant pool for technical jobs in artificial intelligence (AI) and data science is often less than 1% female. To highlight this difference, in 2009 there were 2.5 million college-educated women working in STEM compared to 6.7 million men. The total workforce at the time was 49% women and 51% men which highlights the evident gap.

While the gender gap in digital skills is evident across regional boundaries and income levels, it is more severe for women who are older, less educated, poor, or living in rural areas and developing countries. Making women much less likely to graduate in any field of STEM compared to their male counterpart. Digital skills gap intersects with issues of poverty and educational access.

Root causes

Women and girls may struggle to access public ICT facilities due to unsafe roads, limits on their freedom of movement, or because the facilities themselves are considered unsuitable for women.

Women may not have the financial independence needed to purchase digital technology or pay for internet connectivity. Digital access, even when available, may be controlled and monitored by men or limited to ‘walled gardens’ containing a limited selection of content, known as ‘pink content’ focused on women's appearances, dating, or their roles as wives or mothers. Fears concerning safety and harassment (both online and offline) also inhibit many women and girls from benefiting from or even wanting to use ICTs.

In many contexts, women and girls face concerns of physical violence if they own or borrow digital devices, which in some cases leads to their using the devices in secret, making them more vulnerable to online threats and making it difficult to gain digital skills.

The stereotype of technology as a male domain is common in many contexts and affect girls’ confidence in their digital skills from a young age. In OECD countries, 0.5% of girls aspire towards ICT-related careers at age 15, versus 5% of boys. This was not always the case. At the beginning of electronic computing following the Second World War, software programming in industrialized countries was considered ‘women’s work’. Managers of early technology firms allowed women well-suited for programming because of stereotypes characterizing them as meticulous and good at following step-by-step directions. Women, including many women of colour, flocked to jobs in the computer industry because it was seen as more meritocratic than other fields. As computers became integrated into people's daily life, it was noticed that programmers had influence. Consequently, women were pushed out and the field became more male-dominated.

Access divide versus skills divide

Due to the declining price of connectivity and hardware, skills deficits have exceeded barriers of access as the primary contributor to the gender digital divide. For years, the divide was assumed to be symptomatic of technical challenges. It was thought that women would catch up with men when the world had cheaper devices and lower connectivity prices, due to the limited purchasing power and financial independence of women compared with men. The cost of ICT access remains an issue and is surpassed by educational gaps. For example, the gender gap in internet penetration is around 17% in the Arab States and the Asia and Pacific region, whereas the gender gap in ICT skills is as high as 25% in some Asian and Middle Eastern countries. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the Internet penetration rate in 2019 was 33.8 percent for men and 22.6 percent for women. The Internet user gender gap was 20.7 percent in 2013 and up to 37 percent in 2019. The Internet user gender gap was 20.7 percent in 2013 and up to 37 percent in 2019. The Internet penetration rate in 2019 was 33.8 percent for men and 22.6 percent for women.

SSA has one of the widest mobile gender gaps in the world where over 74 million women are not connected. The gender gap in mobile ownership was 13 percent, a reduction from 14 percent in 2018; however, in low- and middle-income countries it remains substantial with fewer women than men accessing the Internet on a mobile device. Furthermore, women are less likely to use digital services or mobile Internet and tend to use different mobile services than men.

Many people have access to affordable devices and broadband networks, but do not have the requisite skills to take advantage of this technology to improve their lives. In Brazil, lack of skills (rather than cost of access) was found to be the primary reason low-income groups are not using the internet. In India, where lack of skills and lack of need for the internet were the primary limiting factors across all income groups.

Lack of understanding, interest or time is a bigger issue than affordability or availability as the reason for not using the internet. Even though skills deficits prevent both men and women from using digital technologies, they tend to be more severe for women. In a study conducted across 10 low- and middle-income countries, women were 1.6 times more likely than men to report lack of skills as a barrier to internet use. Women are also more likely to report that they do not see a reason to access and use ICT. Interest and perception of need are related to skills, as people who have little experience with or understanding of ICTs tend to underestimate their benefits and utility.

Relationship between digital skills and gender equality

In many societies, gender equality does not translate into gender equality in digital realms and digital professions. The persistence of growing digital skills gender gaps, even in countries that rank at the top of the World Economic Forum's global gender gap index (reflecting strong gender equality), demonstrates a need for interventions that cultivate the digital skills of women and girls.

For most countries, the primary barriers for women regarding access to digital technology are cost/unaffordability followed by illiteracy and lack of digital skills. For instance, in Africa 65.4 percent of people aged 15 and older are illiterate, compared to the global average rate of 86.4 percent.

Gender digital divide and COVID-19

Africa

The COVID-19 pandemic and the measures taken by governments on social distancing and mobility restrictions have contributed to boosting the use of digital technology to bridge some of the physical access gaps. However, the rapid proliferation of digital tools and services stands in stark contrast to the many systemic and structural barriers to technology access and adoption that many people in rural Africa still face. Gender inequalities, intersecting with and compounded by other social differences such as class, race, age, (dis)ability, etc., shape the extent to which different rural women and men are able not only to access but also use and benefit from these new technologies and ways of delivering information and services.

Beside the potential of digital tools and applications, the COVID-19 crisis has evidenced the existing digital divide and especially the gender gap. It is estimated that 3.6 billion individuals are not connected to the Internet across the globe, including 900 million in Africa. Only 27 percent of women in Africa have access to the Internet and only 15 percent of them can afford to use it.

Gender-responsive digitalization in COVID-19 response

According to a study by FAO, gender-responsive digitalization in COVID-19 response and beyond could include:

- Improve the availability of sex-disaggregated data and gender-related statistics that capture digital gender gaps in rural areas to better inform policy and business decisions

- Promote an enabling environment that includes gender-responsive policies, strategies and initiatives

- Leverage digital solutions to deliver COVID-19 relief measures targeted to rural women and girls and facilitate their access to social protection services and alternative income-generation opportunities.

- Dedicate funds for digital acceleration to support women-led enterprises.

- Improve the national broadband coverage to ensure affordable, accessible and reliable infrastructure for inclusive digital transformation

- Invest in the protection of Internet users, especially illiterate and vulnerable ones, against frauds and abuses as cybercrime, including sexual harassment. According to UN Women, these crimes have reportedly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially toward women and girls.

Benefits of digital empowerment

Helping women and girls develop digital skills means stronger women, stronger families, stronger communities, stronger economies and better technology. Digital skills is recognized to be essential life skills required for full participation in society. The main benefits for acquiring digital skills are they:

- Facilitate entry into the labour market;

- Assist women's safety both online and offline;

- Enhance women's community and political engagement;

- Bring economic benefits to women and society;

- Empower women to help steer the future of technology and gender equality;

- Accelerate progress towards international goals.

Digitalization can potentially pave the way for improving the efficiency and functioning of food systems, which in turn can have positive impacts on the livelihoods of women and men farmers and agripreneurs, for example, through the creation of digital job opportunities for young women and men in rural areas.

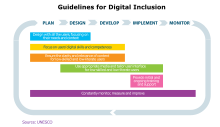

Closing the digital skills gender gap

Increasing girls’ and women's digital skills involves early, varied and sustained exposure to digital technologies. Interventions should not be limited to formal education settings, they should reflect a multifaceted approach, enabling women and girls to acquire skills in a variety of formal and informal contexts (at home, in school, in their communities and in the workplace). The digital divide cuts across age groups, therefore solutions need to assume a lifelong learning orientation. The technological changes adds impetus to the ‘across life’ perspective, as skills learned today will not necessarily be relevant in 5 or 10 years. Digital skills require regular updating, to prevent women and girls fall further behind.

Women and girls digital skills development are strengthened by:

- Adopting sustained, varied and life-wide approaches;

- Establishing incentives, targets and quotas;

- Embedding ICT in formal education;

- Supporting engaging experiences;

- Emphasising meaningful use and tangible benefits;

- Encouraging collaborative and peer learning;

- Creating safe spaces and meet women where they are;

- Examining exclusionary practices and language;

- Recruiting and training gender-sensitive teachers;

- Promoting role models and mentors;

- Bringing parents on board;

- Leveraging community connections and recruiting allies;

- Supporting technology autonomy and women's digital rights.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), there are seven success factors to empowering rural women through ICTs:

- Adapt content so that it is meaningful for them.

- Create a safe environment for them to share and learn.

- Be gender-sensitive.

- Provide them with access and tools for sharing

- Build partnerships.

- Provide the right blend of technologies.

- Ensure sustainability

The regulatory role of governments (at local, national, regional, and international levels) is crucial in addressing infrastructural barriers, harmonizing and making the regulatory environment inclusive and gender-responsive, and in protecting all stakeholders from fraud and crime.

Initiatives targeted at boosting women's representation in the technology industry are essential to closing the digital skills gender divide. Mentorship programs, networking chances, and scholarships for women seeking jobs in technology are examples of such initiatives. These efforts can help create more inclusive workplaces that respect diversity and promote creativity by boosting the presence of women in the technology industry.

- Mentorship programs can be especially beneficial in assisting women in the technology industry. These initiatives allow women to network with experienced professionals who can give advice and support as they advance in their jobs. According to research, mentoring programs can help increase women's confidence and feeling of connection in the workplace, which can improve job happiness and professional growth opportunities.

- Women in technology can benefit from networking chances as well. Women can benefit from networking by developing connections with other professionals in their industry, which can lead to new employment possibilities and collaborations. Networking can also assist women in staying current with the newest trends and technologies in their profession.

- Scholarships can also be a good method to help women who want to work in technology. Scholarships can assist in covering the costs of education and training, making it simpler for women to gain the skills and knowledge required to thrive in the technology industry. Scholarships can also help to increase gender variety in the technology industry by encouraging more women to enter the profession.

Overall, initiatives targeted at boosting women's representation in the technology industry are essential to closing the digital skills gender divide. We can build more inclusive and innovative environments that help everyone if we assist women in technology.

Female gendering of AI technologies

Men continue to dominate the technology space, and the disparity serves to perpetuate gender inequalities, as unrecognized bias is replicated and built into algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI).

Limited participation of women and girls in the technology sector can stem outward replicating existing gender biases and creating new ones. Women's participation in the technology sector is constrained by unequal digital skills education and training. Learning and confidence gaps that arise as early as primary school amplify as girls move through education, therefore by the time they reach higher education only a fraction pursue advanced-level studies in computer science and related information and communication technology (ICT) fields. Divides grow greater in the transition from education to work. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) estimates that only 6% of professional software developers are women.

Technologies generated by male-dominated teams and companies often reflect gender biases. Establishing balance between men and women in the technology sector will help lay foundations for the creation of technology products that better reflect and ultimately accommodate the rich diversity of human societies. For instance AI, which is a branch of the technology sector that wields influence over people's lives. Today, AI curates information shown by internet search engines, determines medical treatments, makes loan decisions, ranks job applications, translates languages, places ads, recommends prison sentences, influences parole decisions, calibrates lobbying and campaigning efforts, intuits tastes and preferences, and decides who qualifies for insurance, among other tasks. Despite the growing influence of this technology, women make up just 12% of AI researchers. Closing the gender divide begins with establishing more inclusive and gender-equal digital skills education and training.

Digital assistants

Digital assistants encompass a range of internet-connected technologies that support users in various ways. When interacting with digital assistants, users are not restricted to a narrow range of input commands, but are encouraged to make queries using whichever inputs seem most appropriate or natural, whether they are typed or spoken. Digital assistants seek to enable and sustain more human-like interactions with technology. Digital assistants can include: voice assistants, chatbots, and virtual agents.

Feminization of voice assistants

Voice assistants have become central to technology platforms and, in many countries, to day-to-day life. Between 2008 and 2018, the frequency of voice-based internet search queries increased 35 times and account for close to one fifth of mobile internet searches (a figure that is projected to increase to 50% by 2020). Voice assistants now manage upwards of 1 billion tasks per month, from the mundane (changing a song) to the essential (contacting emergency services).

Today, most leading voice assistants are exclusively female or female by default, both in name and in sound of voice. Amazon has Alexa (named for the ancient library in Alexandria), Microsoft has Cortana (named for a synthetic intelligence in the video game Halo that projects itself as a sensuous unclothed woman), and Apple has Siri (coined by the Norwegian co-creator of the iPhone 4S and meaning ‘beautiful woman who leads you to victory’ in Norse). While Google's voice assistant is simply Google Assistant and sometimes referred to as Google Home, its voice is female.

The trend to feminize assistants occurs in a context in which there is a growing gender imbalance in technology companies, such that men commonly represent two thirds to three quarters of a firm's total workforce. Companies like Amazon and Apple have cited academic work demonstrating that people prefer a female voice to a male voice, justifying the decision to make voice assistants female. Further research shows that consumers strongly dislike voice assistants without clear gender markers. This puts away questions of gender bias, meaning that companies make a profit by attracting and pleasing customers. Research shows that customers want their digital assistants to sound like women, therefore digital assistants can make the most profit by sounding female.

Researchers who specialize in human–computer interaction have recognized that both men and women tend to characterize female voices as more helpful. The perception may have roots in traditional social norms around women as nurturers (mothers often take on – willingly or not – significantly more care than fathers) and other socially constructed gender biases that predate the digital era.