| Shell shock | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bullet air, soldier's heart, battle fatigue, operational exhaustion |

| |

| A soldier displaying the characteristic thousand-yard stare associated with shell shock. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Shell shock is a word that originated during World War I to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that many soldiers experienced during the war, before PTSD was officially recognized. It is a reaction to the intensity of the bombardment and fighting that produced a helplessness, which could manifest as panic, fear, flight, or an inability to reason, sleep, walk or talk.

During the war, the concept of shell shock was poorly defined. Cases of "shell shock" could be interpreted as either a physical or psychological injury, or as a lack of moral fibre. Although the United States’ Department of Veterans Affairs still uses the term shell shock to describe certain aspects of PTSD, it is mostly a historical term, and is often considered to be the signature injury of the war.

In World War II and beyond, the diagnosis of "shell shock" was replaced by that of combat stress reaction, which is a similar but not identical response to the trauma of warfare and bombardment.

Origin

During the early stages of World War I in 1914, soldiers from the British Expeditionary Force began to report medical symptoms after combat, including tinnitus, amnesia, headaches, dizziness, tremors, and hypersensitivity to noise. While these symptoms resembled those that would be expected after a physical wound to the brain, many of those reporting sick showed no signs of head wounds. By December 1914, as many as 10% of British officers and 4% of enlisted men were experiencing "nervous and mental shock".

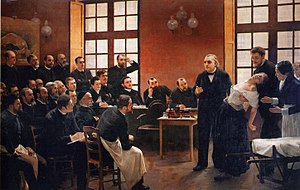

The term "shell shock" was coined during the Battle of Loos to reflect an assumed link between the symptoms and the effects of explosions from artillery shells. The term was first published in 1915 in an article in The Lancet by Charles Myers. Some 60–80% of shell shock cases displayed acute neurasthenia, while 10% displayed what would now be termed symptoms of conversion disorder, including mutism and fugue.

The number of shell shock cases grew during 1915 and 1916 but it remained poorly understood medically and psychologically. Some physicians held the view that it was a result of hidden physical damage to the brain, with the shock waves from bursting shells creating a cerebral lesion that caused the symptoms and could potentially prove fatal. Another explanation was that shell shock resulted from poisoning by the carbon monoxide formed by explosions.

At the same time, an alternative view developed describing shell shock as an emotional, rather than a physical, injury. Evidence for this point of view was provided by the fact that an increasing proportion of men with shell shock symptoms had not been exposed to artillery fire. Since the symptoms appeared in men who had no proximity to an exploding shell, the physical explanation was clearly unsatisfactory.

In spite of this evidence, the British Army continued to try to differentiate those whose symptoms followed explosive exposure from others. In 1915 the British Army in France was instructed that:

Shell-shock and shell concussion cases should have the letter 'W' prefixed to the report of the casualty, if it was due to the enemy; in that case the patient would be entitled to rank as 'wounded' and to wear on his arm a 'wound stripe'. If, however, the man's breakdown did not follow a shell explosion, it was not thought to be 'due to the enemy', and he was to [be] labelled 'Shell-shock' or 'S' (for sickness) and was not entitled to a wound stripe or a pension.

However, it often proved difficult to identify which cases were which, as the information on whether a casualty had been close to a shell explosion or not was rarely provided.

Management

Acute

At first, shell-shock casualties were rapidly evacuated from the front line – in part because of fear over their frequently dangerous and unpredictable behaviour. As the size of the British Expeditionary Force increased, and manpower became in shorter supply, the number of shell shock cases became a growing problem for the military authorities. At the Battle of the Somme in 1916, as many as 40% of casualties were shell-shocked, resulting in concern about an epidemic of psychiatric casualties, which could not be afforded in either military or financial terms.

Among the consequences of this were an increasing official preference for the psychological interpretation of shell shock, and a deliberate attempt to avoid the medicalisation of shell shock. If men were 'uninjured' it was easier to return them to the front to continue fighting. Another consequence was an increasing amount of time and effort devoted to understanding and treating shell shock symptoms. Soldiers who returned with shell shock generally could not remember much because their brain would shut out all the traumatic memories.

By the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, the British Army had developed methods to reduce shell shock. A man who began to show shell-shock symptoms was best given a few days' rest by his local medical officer. Col. Rogers, Regimental Medical Officer, 4th Battalion Black Watch wrote:

You must send your commotional cases down the line. But when you get these emotional cases, unless they are very bad, if you have a hold of the men and they know you and you know them (and there is a good deal more in the man knowing you than in you knowing the man) … you are able to explain to him that there is really nothing wrong with him, give him a rest at the aid post if necessary and a day or two’s sleep, go up with him to the front line, and, when there, see him often, sit down beside him and talk to him about the war and look through his periscope and let the man see you are taking an interest in him.

If symptoms persisted after a few weeks at a local Casualty Clearing Station, which would normally be close enough to the front line to hear artillery fire, a casualty might be evacuated to one of four dedicated psychiatric centres which had been set up further behind the lines, and were labelled as "NYDN – Not Yet Diagnosed Nervous" pending further investigation by medical specialists.

Although the Battle of Passchendaele generally became a byword for horror, the number of cases of shell shock were relatively few. 5,346 shell shock cases reached the Casualty Clearing Station, or roughly 1% of the British forces engaged. 3,963 (or just under 75%) of these men returned to active service without being referred to a hospital for specialist treatment. The number of shell shock cases reduced throughout the battle, and the epidemic of illness was ended.

During 1917, "shell shock" was entirely banned as a diagnosis in the British Army, and mentions of it were censored, even in medical journals.

Chronic treatment

The treatment of chronic shell shock varied widely according to the details of the symptoms, the views of the doctors involved, and other factors including the rank and class of the patient.

There were so many officers and men with shell shock that 19 British military hospitals were wholly devoted to the treatment of cases. Ten years after the war, 65,000 veterans of the war were still receiving treatment for it in Britain. In France it was possible to visit aged shell shock victims in hospital in 1960.

Physical causes

Research by Johns Hopkins University in 2015 found that the brain tissue of combat veterans who had been exposed to improvised explosive devices (IEDs) exhibited a pattern of injury in the areas responsible for decision making, memory and reasoning. This evidence has led the researchers to conclude that shell shock may not only be a psychological disorder, since the symptoms exhibited by affected individuals from the First World War are very similar to these injuries. Immense pressure changes are involved in shell shock. Even mild changes in air pressure from weather have been linked to changes in behavior.

There is also evidence to suggest that the type of warfare faced by soldiers would affect the probability of shell shock symptoms developing. First-hand reports from medical doctors at the time note that rates of such conditions decreased once the war was mobilized again during the 1918 German offensive, following the 1916–1917 period where the highest rates of shell shock can be found. This could suggest that it was trench warfare, and the experience of siege warfare specifically, that led to the development of these symptoms.

Cowardice

Some men with shell shock were put on trial, and even executed, for military crimes including desertion and cowardice. While it was recognised that the stresses of war could cause men to break down, a lasting episode was likely to be seen as symptomatic of an underlying lack of character. For instance, in his testimony to the post-war Royal Commission examining shell shock, Lord Gort said that shell shock was a weakness and was not found in "good" units. The continued pressure to avoid medical recognition of shell shock meant that it was not, in itself, considered an admissible defence. Although some doctors or medics did take procedure to try to cure soldiers' shell shock, it was first done in a brutal way. Doctors would provide electric shock to soldiers in hopes that it would shock them back to their normal, heroic, pre-war self. While illustrating cases of mutism in his book Hysterical Disorders of Warfare, therapist Lewis Yealland describes a patient who had over the course of 9 months been subjected unsuccessfully to numerous treatments for his mutism. These included strong application of electricity to his throat, lit cigarette ends had been applied to the tip of his tongue, and "hot plates" had been placed in the back of his mouth.

Executions of soldiers in the British Army were not commonplace. While there were 240,000 Courts Martial and 3080 death sentences handed down, in only 346 cases was the sentence carried out. 266 British soldiers were executed for "Desertion", 18 for "Cowardice", 7 for "Quitting a post without authority", 5 for "Disobedience to a lawful command" and 2 for "Casting away arms". On 7 November 2006, the government of the United Kingdom gave them all a posthumous conditional pardon.

Committee of Enquiry report

The British government produced a Report of the War Office Committee of Enquiry into "Shell-Shock" which was published in 1922. Recommendations from this included:

- In forward areas

- No soldier should be allowed to think that loss of nervous or mental control provides an honourable avenue of escape from the battlefield, and every endeavour should be made to prevent slight cases leaving the battalion or divisional area, where treatment should be confined to provision of rest and comfort for those who need it and to heartening them for return to the front line.

- In neurological centres

- When cases are sufficiently severe to necessitate more scientific and elaborate treatment they should be sent to special Neurological Centres as near the front as possible, to be under the care of an expert in nervous disorders. No such case should, however, be so labelled on evacuation as to fix the idea of nervous breakdown in the patient’s mind.

- In base hospitals

- When evacuation to the base hospital is necessary, cases should be treated in a separate hospital or separate sections of a hospital, and not with the ordinary sick and wounded patients. Only in exceptional circumstances should cases be sent to the United Kingdom, as, for instance, men likely to be unfit for further service of any kind with the forces in the field. This policy should be widely known throughout the Force.

- Forms of treatment

- The establishment of an atmosphere of cure is the basis of all successful treatment, the personality of the physician is, therefore, of the greatest importance. While recognising that each individual case of war neurosis must be treated on its merits, the Committee are of opinion that good results will be obtained in the majority by the simplest forms of psycho-therapy, i.e., explanation, persuasion and suggestion, aided by such physical methods as baths, electricity and massage. Rest of mind and body is essential in all cases.

- The committee are of opinion that the production of hypnoidal state and deep hypnotic sleep, while beneficial as a means of conveying suggestions or eliciting forgotten experiences are useful in selected cases, but in the majority they are unnecessary and may even aggravate the symptoms for a time.

- They do not recommend psycho-analysis in the Freudian sense.

- In the state of convalescence, re-education and suitable occupation of an interesting nature are of great importance. If the patient is unfit for further military service, it is considered that every endeavour should be made to obtain for him suitable employment on his return to active life.

- Return to the fighting line

- Soldiers should not be returned to the fighting line under the following conditions:

- (1) If the symptoms of neurosis are of such a character that the soldier cannot be treated overseas with a view to subsequent useful employment.

- (2) If the breakdown is of such severity as to necessitate a long period of rest and treatment in the United Kingdom.

- (3) If the disability is anxiety neurosis of a severe type.

- (4) If the disability is a mental breakdown or psychosis requiring treatment in a mental hospital.

- It is, however, considered that many of such cases could, after recovery, be usefully employed in some form of auxiliary military duty.

Part of the concern was that many British veterans were receiving pensions and had long-term disabilities.

By 1939, some 120,000 British ex-servicemen had received final awards for primary psychiatric disability or were still drawing pensions – about 15% of all pensioned disabilities – and another 44,000 or so … were getting pensions for ‘soldier’s heart’ or Effort Syndrome. There is, though, much that statistics do not show, because in terms of psychiatric effects, pensioners were just the tip of a huge iceberg.

War correspondent Philip Gibbs wrote:

Something was wrong. They put on civilian clothes again and looked to their mothers and wives very much like the young men who had gone to business in the peaceful days before August 1914. But they had not come back the same men. Something had altered in them. They were subject to sudden moods, and queer tempers, fits of profound depression alternating with a restless desire for pleasure. Many were easily moved to passion where they lost control of themselves, many were bitter in their speech, violent in opinion, frightening.

One British writer between the wars wrote:

There should be no excuse given for the establishment of a belief that a functional nervous disability constitutes a right to compensation. This is hard saying. It may seem cruel that those whose sufferings are real, whose illness has been brought on by enemy action and very likely in the course of patriotic service, should be treated with such apparent callousness. But there can be no doubt that in an overwhelming proportion of cases, these patients succumb to ‘shock’ because they get something out of it. To give them this reward is not ultimately a benefit to them because it encourages the weaker tendencies in their character. The nation cannot call on its citizens for courage and sacrifice and, at the same time, state by implication that an unconscious cowardice or an unconscious dishonesty will be rewarded.

Development of psychiatry

At the beginning of World War II, the term "shell shock" was banned by the British Army, though the phrase "postconcussional syndrome" was used to describe similar traumatic responses.

Society and culture

Shell shock has had a profound impact in British culture and the popular memory of World War I. At the time, war writers like the poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen dealt with shell shock in their work. Sassoon and Owen spent time at Craiglockhart War Hospital, which treated shell shock casualties. Author Pat Barker explored the causes and effects of shell shock in her Regeneration Trilogy, basing many of her characters on real historical figures and drawing on the writings of the first world war poets and the army doctor W. H. R. Rivers.

Modern cases of shell shock

Although the term "shell shocked" is typically used in discussion of WWI to describe early forms of PTSD, its high-impact explosives-related nature provides modern applications as well. During their deployment in Iraq and Afghanistan, approximately 380,000 U.S. troops, about 19% of those deployed, were estimated to have sustained brain injuries from explosive weapons and devices. This prompted the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to open up a $10 million study of the blast effects on the human brain. The study revealed that, while the brain remains initially intact immediately after low level blast effects, the chronic inflammation afterwards is what ultimately leads to many cases of shell shock and PTSD.