Nomadic empires, sometimes also called steppe empires, Central or Inner Asian empires, were the empires erected by the bow-wielding, horse-riding, nomadic people in the Eurasian Steppe, from classical antiquity (Scythia) to the early modern era (Dzungars). They are the most prominent example of non-sedentary polities.

Some nomadic empires consolidated by establishing a capital city inside a conquered sedentary state and then exploiting the existing bureaucrats and commercial resources of that non-nomadic society. In such a scenario, the originally nomadic dynasty may become culturally assimilated to the culture of the occupied nation before it is ultimately overthrown. Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) described a similar cycle on a smaller scale in 1377 in his Asabiyyah theory.

Historians of the early medieval period may refer to these polities as "khanates" (after khan, the title of their rulers). After the Mongol conquests of the 13th century the term orda ("horde") also came into use — as in "Golden Horde".

Background

In the history of China, Central Plain polities relied on horses to resist nomadic incursions into their territories, but was only able to purchase the needed horses from the nomads. Trading in horses actually gave these nomadic groups the means to acquire goods by commercial means and reduced the number of attacks and raids into the territories of Central Plain regimes.

Nomads were generally unable to hold onto conquered territories for long without reducing the size of their cavalry forces because of the limitations of pasture in a settled lifestyle. Therefore, settled civilizations usually became reliant on nomadic ones to provide the supply of horses as needed—because they did not have resources to maintain these numbers of horses themselves.

Camel-oriented Bedouin societies in Arabia have functioned as desert-based analogues of Central-Asian horse-oriented nomadic empires.

History

Ancient history

Cimmeria

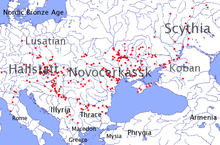

The Cimmerians were an ancient Indo-European people living north of the Caucasus and the Sea of Azov as early as 1300 BCE until they were driven southward by the Scythians into Anatolia during the 8th century BCE. Linguistically they are usually regarded as Iranian, or possibly Thracian with an Iranian ruling class.

- The Pontic–Caspian steppe: southern Russia and Ukraine until 7th century BCE.

- The northern Caucasus area, including Georgia and modern day Azerbaijan

- Central, East and North Anatolia 714–626 BCE.

Scythia

Scythia (/ˈsɪθiə/; Ancient Greek: Σκυθική) was a region of Central Eurasia in classical antiquity, occupied by the Eastern Iranian Scythians, encompassing parts of Eastern Europe east of the Vistula River and Central Asia, with the eastern edges of the region vaguely defined by the Greeks. The Ancient Greeks gave the name Scythia (or Great Scythia) to all the lands north-east of Europe and the northern coast of the Black Sea. The Scythians—the Greeks' name for this initially nomadic people—inhabited Scythia from at least the 11th century BCE to the 2nd century CE.

Sarmatia

The Sarmatians (Latin: Sarmatæ or Sauromatæ; Ancient Greek: Σαρμάται, Σαυρομάται) were a large confederation of Iranian people during classical antiquity, flourishing from about the 6th century BCE to the 4th century CE. They spoke Scythian, an Indo-European language from the Eastern Iranian family. According to authors Arrowsmith, Fellowes and Graves Hansard in their book A Grammar of Ancient Geography published in 1832, Sarmatia had two parts, Sarmatia Europea and Sarmatia Asiatica covering a combined area of 503,000 sq mi or 1,302,764 km2. Sarmatians were basically Scythian veterans (Saka, Iazyges, Skolotoi, Parthians...) returning to the Pontic–Caspian steppe after the siege of Nineveh. Many noble families of Polish Szlachta claimed a direct descent from Sarmatians as a part of Sarmatism.

Xiongnu

The Xiongnu were a confederation of nomadic tribes from northern China and Inner Asia with a ruling class of unknown origin and other subjugated tribes. They lived on the Mongolian Plateau between the 3rd century BCE and the 460s CE, their territories including the modern-day northern China, Mongolia, southern Siberia. The Xiongnu was the first unified empire of nomadic peoples. Relations between early Central Plain dynasties and the Xiongnu were complicated and included military conflict, exchanges of tribute and trade, and marriage alliances. When Qin Shi Huang drove them away from the south of the Yellow River, he built the Great Wall to prevent the Xiongnu from returning.

Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi who originally hailed from the modern-day Chinese province of Gansu under the pressure of the Xiongnu, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of modern-day Afghanistan, and then the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan emperor Kanishka the Great.

Xianbei

The Xianbei state or Xianbei confederation was a nomadic empire which existed in modern-day Inner Mongolia, northern Xinjiang, Northeast China, Gansu, Mongolia, Buryatia, Zabaykalsky Krai, Irkutsk Oblast, Tuva, Altai Republic and eastern Kazakhstan from 156 to 234 CE. Like most ancient peoples known through Chinese historiography, the ethnic makeup of the Xianbei is unclear. The Xianbei were a northern branch of the earlier Donghu and it is likely at least some were proto-Mongols. After it collapsed, the tribe immigrated into the Central Plain and founded the Northern Wei dynasty.

Hephthalite Empire

The Hephthalites, Ephthalites, Ye-tai, White Huns, or, in Sanskrit, the Sveta Huna, were a confederation of nomadic and settled people in Central Asia who expanded their domain westward in the 5th century. At the height of its power in the first half of the 6th century, the Hephthalite Empire controlled territory in present-day Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, India and China.

Hunnic Empire

The Huns were a confederation of Eurasian tribes from the Steppes of Central Asia. Appearing from beyond the Volga River some years after the middle of the 4th century, they conquered all of eastern Europe, ending up at the border of the Roman Empire in the south, and advancing far into modern day Germany in the north. Their appearance in Europe brought with it great ethnic and political upheaval and may have stimulated the Great Migration. The empire reached its largest size under Attila between 447 and 453.

Post-classical history

Mongolic people and Turkic expansion

Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. Emerging as nomadic equestrians in the Volga-Ural region, according to some researchers their roots can be traced to Central Asia. During their westward migration across the Eurasian steppe the Bulgars absorbed other ethnic groups and cultural influences, including Hunnic and Indo-European peoples. Modern genetic research on Central Asian Turkic people and ethnic groups related to the Bulgars points to an affiliation with Western Eurasian populations. The Bulgars spoke a Turkic language, i.e. Bulgar language of Oghuric branch. They preserved the military titles, organization and customs of Eurasian steppes, as well as pagan shamanism and belief in the sky deity Tangra.

After Dengizich's death, the Huns seem to have been absorbed by other ethnic groups such as the Bulgars. Kim, however, argues that the Huns continued under Ernak, becoming the Kutrigur and Utigur Hunno-Bulgars. This conclusion is still subject to some controversy. Some scholars also argue that another group identified in ancient sources as Huns, the North Caucasian Huns, were genuine Huns. The rulers of various post-Hunnic steppe peoples are known to have claimed descent from Attila in order to legitimize their right to the power, and various steppe peoples were also called "Huns" by Western and Byzantine sources from the fourth century onward.

The first clear mention and evidence of the Bulgars was in 480, when they served as the allies of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno (474–491) against the Ostrogoths. Anachronistic references about them can also be found in the 7th-century geography work Ashkharatsuyts by Anania Shirakatsi, where the Kup'i Bulgar, Duč'i Bulkar, Olxontor Błkar and immigrant Č'dar Bulkar tribes are mentioned as being in the North Caucasian-Kuban steppes. An obscure reference to Ziezi ex quo Vulgares, with Ziezi being an offspring of Biblical Shem, is in the Chronography of 354.

The Bulgars became semi-sedentary during the 7th century in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, establishing the polity of Old Great Bulgaria c. 635, which was absorbed by the Khazar Empire in 668 CE.

In c. 679, Khan Asparukh conquered Scythia Minor, opening access to Moesia, and established the First Bulgarian Empire, where the Bulgars became a political and military elite. They merged subsequently with established Byzantine populations, as well as with previously settled Slavic tribes, and were eventually Slavicized, thus forming the ancestors of modern Bulgarians.

Rouran

The Rouran (柔然), Juan Juan (蠕蠕), or Ruru (茹茹) were a confederation of Mongolic-speaking nomadic tribes in northern China from the late 4th century until the late 6th century. They controlled an area corresponding to modern-day northern China, Mongolia, and southern Siberia.

Göktürks

The Göktürks or Kök-Türks were a Turkic people of inhabiting much of northern China and Inner Asia. Under the leadership of Bumin Khan and his sons they established the First Turkic Khaganate around 546, taking the place of the earlier Xiongnu as the main power in the region. They were the first Turkic tribe to use the name Türk as a political name. The empire was split into a western and an eastern part around 600, and both divisions were eventually conquered by the Tang dynasty. In 680, the Göktürks established the Second Turkic Khaganate which later declined after 734 following the establishment of the Uyghur Khaganate.

Kyrgyz

The Yenisei Kyrgyz Khaganate was a Turkic-led empire occupying the territories of modern-day northern China, Mongolia, and southern Siberia around the Yenisei River. The khaganate was founded in 693 by Bars Bek, and in 695, after a confrontation with the Second Turkic Khaganate, was recognised by Qapagan. In 710–711, as a result of the war with the Göktürks, the Kyrgyz Khaganate fell, and the descendants of Bars Bek remained vassals of the Second Turkic Khaganate until its fall in 744. After that, the Kyrgyz tribes became part of the ascendant Uyghur Khaganate. In 820, war broke out between the Kyrgyz and the Uyghur Khaganate, which continued with varying success for 20 years. In 840, the Uyghur Khaganate fell, and the Kyrgyz Khaganate was restored on its territory. It reached its peak of power at the end of the 9th century, but had little geopolitical influence thereafter. Eventually, the Kyrgyz Khaganate was finally dissolved in 1207 after becoming part of the Mongol Empire.

Uyghurs

The Uyghur Khaganate was an empire that existed in present-day northern China, Mongolia, southern Siberia, and surrounding areas for about a century between the mid 8th and 9th centuries. It was a tribal confederation under the Orkhon Uyghur nobility. It was established by Kutlug I Bilge Kagan in 744, taking advantage of the power vacuum in the region after the fall of the Gökturk Empire. It collapsed after a Kyrgyz invasion in 840.

Khitans

The Liao dynasty was ruled by the Yelü clan of the Khitan people in northern China. It was founded by Yelü Abaoji (Emperor Taizu of Liao) around the time of the collapse of the Tang dynasty and was the first state to control all of Manchuria. After the Liao dynasty fell to the Jin dynasty in the 12th century, remnants of the Liao imperial clan led by Yelü Dashi (Emperor Dezong of Western Liao) fled west and established the Western Liao dynasty.

Seljuk Empire

The founder of the Seljuk dynasty was an Oghuz Turkic chieftain Seljuk that had served under Khazar army. Ancestors of Seljuk remained unclarified except for his father, Dukak. Dukak was a competent man in Oghuz Yabgu State, and like him Seljuk also gained a seat the court of the Oghuz Yabgu. Afterwards Seljuk fell into disfavor in the court, and he decided to move into Jend with his clan in 961. Rumor has it that he converted to İslam in order to gain the power from İslamic countries. The Oghuz Turks sought a proper homeland that includes vast pastures for their herdes, and consistently fought against Kara-Khanid Khanate, Ghaznavids and Eastern Roman Empire. They followed changeable policies among contiguous states due to tending to keep the balance of power. The grandsons of Seljuk, Tughril and Chagri Begs decisively defeated Ghaznavids in the Battle of Dandanaqan, gained the power in the Khorasan. Tughril Beg sent Chagri Beg into Eastern Anatolia to seek proper pastures, so the conflicts between Oghuz Turks and Byzantine Empire began. During Tughril's reign, the life styles of nomadic Oghuz tribes changed as they conquered lands of Persia.

Mongol Empire

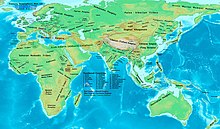

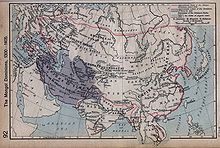

The Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous land empire in history at its peak, with an estimated population of over 100 million people. The Mongol Empire was founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, and at its height, it encompassed the majority of the territories from East Asia to Eastern Europe.

After unifying the Turco-Mongol tribes, the Empire expanded through conquests throughout continental Eurasia. During its existence, the Pax Mongolica facilitated cultural exchange and trade on the Silk Route between the East, West, and the Middle East in the period of the 13th and 14th centuries. It had significantly eased communication and commerce across Asia during its height.

After the death of Möngke Khan in 1259, the empire split into four parts (Yuan dynasty, Ilkhanate, Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde), each of which was ruled by its own monarch, although the emperors of the Yuan dynasty had nominal title of Khagan. After the disintegration of the western khanates and the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, the empire finally broke up.

Timurid Empire

The Timurids, self-designated Gurkānī, were a Turko-Mongol dynasty, established by the warlord Timur in 1370 and lasting until 1506. At its zenith, the Timurid Empire included the whole of Central Asia, Iran and modern Afghanistan, as well as large parts of Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.

Modern history

Later Mongol-ruled khanates

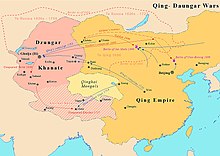

Later Mongol-led khanates such as the Northern Yuan dynasty and the Dzungar Khanate were also nomadic empires. After the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, the Ming dynasty rebuilt the Great Wall, which had been begun many hundreds of years earlier to keep the northern nomads out of the Central Plain. During the subsequent centuries, the Northern Yuan dynasty tended to continue their nomadic way of life. On the other hand, the Dzungars were a confederation of several Oirat tribes who formed and maintained the last horse archer empire from the early 17th century to the middle 18th century. They emerged in the early 17th century to fight the Altan Khan of the Khalkha, the Jasaghtu Khan and their Manchu patrons for dominion and control over the Mongol tribes. In 1756, this last nomadic power was dissolved due to the Oirat princes' succession struggle and costly war with the Qing dynasty.

Popular misconceptions

The Qing dynasty is mistakenly confused as a nomadic empire by people who wrongly think that the Manchus were a nomadic people, when in fact they were not nomads, but instead were a sedentary agricultural people who lived in fixed villages, farmed crops, and practiced hunting and mounted archery.

The Sushen used flint-headed wooden arrows, farmed, hunted, and fished and lived in caves and trees. The cognates Sushen or Jichen (稷真) again appear in the Shan Hai Jing and Book of Wei during the dynastic era referring to Tungusic Mohe tribes of the far northeast. The Mohe enjoyed eating pork, practiced pig farming extensively, and were mainly sedentary, and also used both pig and dog skins for coats. They were predominantly farmers and grew soybean, wheat, millet, and rice, in addition to engaging in hunting.

The Jurchens were sedentary, settled farmers with advanced agriculture. They farmed grain and millet as their cereal crops, grew flax, and raised oxen, pigs, sheep, and horses. Their farming way of life was very different from the pastoral nomadism of the Mongols and the Khitan on the steppes. "At the most", the Jurchen could only be described as "semi-nomadic" while the majority of them were sedentary.

The Manchu way of life (economy) was described as agricultural, with farming crops and raising animals on farms. Manchus practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the areas north of Shenyang. The Haixi Jurchens were "semi-agricultural, the Jianzhou Jurchens and Maolian (毛怜) Jurchens were sedentary, and hunting and fishing was the way of life of the "Wild Jurchens". Han Chinese society resembled that of the sedentary Jianzhou and Maolian, who were farmers. Hunting, archery on horseback, horsemanship, livestock raising, and sedentary agriculture were all practiced by the Jianzhou Jurchens as part of their culture. In spite of the fact that the Manchus practiced archery on horseback and equestrianism, the Manchu's immediate progenitors practiced sedentary agriculture. Although the Manchus also partook in hunting, they were sedentary. Their primary mode of production was farming, and they lived in villages, forts, and towns surrounded by walls. Farming was practiced by their Jurchen Jin predecessors.

“建州毛怜则渤海大氏遗孽,乐住种,善缉纺,饮食服用,皆如华人,自长白山迤南,可拊而治也。" "The (people of) Chien-chou and Mao-lin [YLSL always reads Mao-lien] are the descendants of the family Ta of Po-hai. They love to be sedentary and sow, and they are skilled in spinning and weaving. As for food, clothing and utensils, they are the same as (those used by) the Chinese. (Those living) south of the Ch'ang-pai mountain are apt to be soothed and governed."

— 据魏焕《皇明九边考》卷二《辽东镇边夷考》Translation from Sino-J̌ürčed relations during the Yung-Lo period, 1403–1424 by Henry Serruys

For political reasons, the Jurchen leader Nurhaci chose variously to emphasize either differences or similarities in lifestyles with other peoples like the Mongols. Nurhaci said to the Mongols, "The languages of the Chinese and Koreans are different, but their clothing and way of life is the same. It is the same with us Manchus (Jušen) and Mongols. Our languages are different, but our clothing and way of life is the same." Later, Nurhaci indicated that the bond with the Mongols was not based in any real shared culture. It was for pragmatic reasons of "mutual opportunism" since Nurhaci said to the Mongols, "You Mongols raise livestock, eat meat and wear pelts. My people till the fields and live on grain. We two are not one country and we have different languages."

Only the Mongols and the northern "wild" Jurchen were semi-nomadic, unlike the mainstream Jiahnzhou Jurchens descended from the Jin dynasty who were farmers that foraged, hunted, herded and harvested crops in the Liao and Yalu river basins. They gathered ginseng root, pine nuts, hunted for came pels in the uplands and forests, raised horses in their stables, and farmed millet and wheat in their fallow fields. They engaged in dances, wrestling and drinking strong liquor as noted during midwinter by the Korean Sin Chung-il when it was very cold. These Jurchens who lived in the north-east's harsh cold climate sometimes half sunk their houses in the ground which they constructed of brick or timber and surrounded their fortified villages with stone foundations on which they built wattle and mud walls to defend against attack. Village clusters were ruled by beile, hereditary leaders. They fought each other and dispensed weapons, wives, slaves, and lands to their followers in them. The Jurchens who founded the Qing lived and their ancestors lived in such a way before the Jin. Alongside Mongols and Jurchen clans there were migrants from Liaodong provinces of the Ming dynasty and Joseon living among those Jurchens in a cosmopolitan manner. Nurhaci who was hosting Sin Chung-il was uniting all of them into his own army, having them adopt the Jurchen hairstyle of a long queue and a shaved fore=crown and wearing leather tunics. His armies had black, blue, red, white, and yellow flags. They became the Eight Banners, which was initially capped to 4 and then grew to 8 with three different types of ethnic banners as Han, Mongol and Jurchen were recruited into Nurhaci's forces. Jurchens like Nurhaci spoke both their native Tungusic language and Chinese and adopted the Mongol script for their own language unlike the Jin Jurchen's script, which was derived from Khitan. They adopted Confucian values and practiced their shamanist traditions.

The Qing stationed "New Manchu" Warka foragers in Ningguta and attempted to turn them into normal agricultural farmers like normal Old Manchus, but the Warka just reverted to hunter gathering and requested money to buy cattle for beef broth. The Qing wanted the Warka to become soldier-farmers and imposed that on them, but the Warka simply left their garrison at Ningguta and went back to the Sungari River to their homes to herd, fish, and hunt. The Qing accused them of desertion.

Similarly, the Indo-European dominions, like the Cimmerian, Scythian, Sarmatian or Kushan ones, were not strictly nomadic or strictly empires. They were organized in small Kšatrapies/Voivodeships that sometimes united into a bigger Mandala to repel surrounding despotic empires trying to annex their homelands. Only the pastoral part of the population and military troops migrated frequently, but most of the population lived in organized agricultural and industrial small scale townships, which are called in Europe gords. Examples are the oases of Sogdia and Sparia along the Silk Road (Śaka, Tokarians/Tokharians etc.) and around the Tarim Basin (Tarim mummies, Kingdom of Khotan) or the rural areas of Europe (Sarmatia, Pannonia, Vysperia, Spyrgowa/Spirgovia, Boioaria/Boghoaria...) and Indian subcontinent (Kaśperia, Pandžab etc.). Since the 2nd century BCE), the growing number of Turkic nomads and invaders among them, who adopted their horse-riding, metallurgy, technologies, clothing, and customs caused them to be also often confused with the latter, which mostly occurred in the case of the Scythians (Śaka, Sarmatians, Skolotoi, Iazyges, etc.). In India, the Śaka, although known earlier as Śakya or Kambojas, formed now the Kushan Empire but were confused with the Xionites invading them and were called Mleccha. The Turkic invaders exploited the subdued sedentary Indo-Europeans in agriculture, industry, and warfare (Mamluk, Janissaries). In some rare cases, the enslaved Indo-Europeans may rise to power like Aleksandra (Iškandara) Lisowska or Roxelana.