| Metamorphoses | |

|---|---|

| by Ovid | |

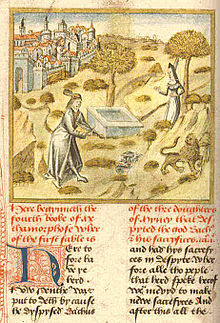

Page from the edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses published by Lucantonio Giunti in Venice, 1497 | |

| Original title | Metamorphoses |

| First published in | 8 CE |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre(s) | Narrative poetry, epic, elegy, tragedy, pastoral (see Contents) |

The Metamorphoses (Latin: Metamorphōsēs, from Ancient Greek: μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his magnum opus. The poem chronicles the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar in a mythico-historical framework comprising over 250 myths, 15 books, and 11,995 lines.

Although it meets some of the criteria for an epic, the poem defies simple genre classification because of its varying themes and tones. Ovid took inspiration from the genre of metamorphosis poetry and some of the Metamorphoses derives from earlier treatment of the same myths; however, he diverged significantly from all of his models.

One of the most influential works in Western culture, the Metamorphoses has inspired such authors as Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, Geoffrey Chaucer, and William Shakespeare. Numerous episodes from the poem have been depicted in works of sculpture, painting, and music, especially during the Renaissance. There was a resurgence of attention to his work towards the end of the 20th century. Today the Metamorphoses continues to inspire and be retold through various media. Numerous English translations of the work have been made, the first by William Caxton in 1480.

Sources and models

Ovid's relation to the Hellenistic poets was similar to the attitude of the Hellenistic poets themselves to their predecessors: he demonstrated that he had read their versions ... but that he could still treat the myths in his own way.

Ovid's decision to make myth the primary subject of the Metamorphoses was influenced by Alexandrian poetry. In that tradition myth functioned as a vehicle for moral reflection or insight, yet Ovid approached it as an "object of play and artful manipulation". The model for a collection of metamorphosis myths was found in the metamorphosis poetry of the Hellenistic tradition, which is first represented by Boio(s)' Ornithogonia—a now-fragmentary poem of collected myths about the metamorphoses of humans into birds.

There are three examples of Metamorphoses by later Hellenistic writers, but little is known of their contents. The Heteroioumena by Nicander of Colophon is better known, and clearly an influence on the poem—21 of the stories from this work were treated in the Metamorphoses. However, in a way that was typical for writers of the period, Ovid diverged significantly from his models. The Metamorphoses was longer than any previous collection of metamorphosis myths (Nicander's work consisted of probably four or five books) and positioned itself within a historical framework.

Some of the Metamorphoses derives from earlier literary and poetic treatment of the same myths. This material was of varying quality and comprehensiveness—while some of it was "finely worked", in other cases Ovid may have been working from limited material. In the case of an oft-used myth such as that of Io in Book I, which was the subject of literary adaptation as early as the 5th century BC, and as recently as a generation prior to his own, Ovid reorganises and innovates existing material in order to foreground his favoured topics and to embody the key themes of the Metamorphoses.

Contents

Scholars have found it difficult to place the Metamorphoses in a genre. The poem has been considered as an epic or a type of epic (for example, an anti-epic or mock-epic); a Kollektivgedicht that pulls together a series of examples in miniature form, such as the epyllion; a sampling of one genre after another; or simply a narrative that refuses categorization.

The poem is generally considered to meet the criteria for an epic; it is considerably long, relating over 250 narratives across fifteen books; it is composed in dactylic hexameter, the meter of both the ancient Iliad and Odyssey, and the more contemporary epic Aeneid; and it treats the high literary subject of myth. However, the poem "handles the themes and employs the tone of virtually every species of literature", ranging from epic and elegy to tragedy and pastoral. Commenting on the genre debate, Karl Galinsky has opined that "... it would be misguided to pin the label of any genre on the Metamorphoses".

The Metamorphoses is comprehensive in its chronology, recounting the creation of the world to the death of Julius Caesar, which had occurred only a year before Ovid's birth; it has been compared to works of universal history, which became important in the 1st century BC. In spite of its apparently unbroken chronology, scholar Brooks Otis has identified four divisions in the narrative:

- Book I – Book II (end, line 875): The Divine Comedy

- Book III – Book VI, 400: The Avenging Gods

- Book VI, 401 – Book XI (end, line 795): The Pathos of Love

- Book XII – Book XV (end, line 879): Rome and the Deified Ruler

Ovid works his way through his subject matter, often in an apparently arbitrary fashion, by jumping from one transformation tale to another, sometimes retelling what had come to be seen as central events in the world of Greek mythology and sometimes straying in odd directions. It begins with the ritual "invocation of the muse", and makes use of traditional epithets and circumlocutions. But instead of following and extolling the deeds of a human hero, it leaps from story to story with little connection.

The recurring theme, as with nearly all of Ovid's work, is love—be it personal love or love personified in the figure of Amor (Cupid). Indeed, the other Roman gods are repeatedly perplexed, humiliated, and made ridiculous by Amor, an otherwise relatively minor god of the pantheon, who is the closest thing this putative mock-epic has to a hero. Apollo comes in for particular ridicule as Ovid shows how irrational love can confound the god out of reason. The work as a whole inverts the accepted order, elevating humans and human passions while making the gods and their desires and conquests objects of low humor.

The Metamorphoses ends with an epilogue (Book XV.871–879), one of only two surviving Latin epics to do so (the other being Statius' Thebaid). The ending acts as a declaration that everything except his poetry—even Rome—must give way to change:

Now stands my task accomplished, such a work

As not the wrath of Jove, nor fire nor sword

Nor the devouring ages can destroy.

Books

- Book I – The Creation, the Ages of Mankind, the flood, Deucalion and Pyrrha, Apollo and Daphne, Io, Phaëton.

- Book II – Phaëton (cont.), Callisto, the Raven and the Crow, Ocyrhoe, Mercury and Battus, the envy of Aglauros, Jupiter and Europa.

- Book III – Cadmus, Diana and Actaeon, Semele and the birth of Bacchus, Tiresias, Narcissus and Echo, Pentheus and Bacchus.

- Book IV – The daughters of Minyas, Pyramus and Thisbe, Mars and Venus, the Sun in love (Leucothoe and Clytie), Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, the daughters of Minyas transformed, Athamas and Ino, the transformation of Cadmus, Perseus and Andromeda.

- Book V – Perseus' fight in the palace of Cepheus, Minerva meets the Muses on Helicon, the rape of Proserpina, Arethusa, Triptolemus.

- Book VI – Arachne; Niobe; the Lycian peasants; Marsyas; Pelops; Tereus, Procne, and Philomela; Boreas and Orithyia.

- Book VII – Medea and Jason, Medea and Aeson, Medea and Pelias, Theseus, Minos, Aeacus, the plague at Aegina, the Myrmidons, Cephalus and Procris.

- Book VIII – Scylla and Minos, the Minotaur, Daedalus and Icarus, Perdix, Meleager and the Calydonian Boar, Althaea and Meleager, Achelous and the Nymphs, Philemon and Baucis, Erysichthon and his daughter.

- Book IX – Achelous and Hercules; Hercules, Nessus, and Deianira; the death and apotheosis of Hercules; the birth of Hercules; Dryope; Iolaus and the sons of Callirhoe; Byblis; Iphis and Ianthe.

- Book X – Orpheus and Eurydice, Cyparissus, Ganymede, Hyacinth, Pygmalion, Myrrha, Venus and Adonis, Atalanta.

- Book XI – The death of Orpheus, Midas, the foundation and destruction of Troy, Peleus and Thetis, Daedalion, the cattle of Peleus, Ceyx and Alcyone, Aesacus.

- Book XII – The expedition against Troy, Achilles and Cycnus, Caenis, the battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, Nestor and Hercules, the death of Achilles.

- Book XIII – Ajax, Ulysses, and the arms of Achilles; the Fall of Troy; Hecuba, Polyxena, and Polydorus; Memnon; the pilgrimage of Aeneas; Acis and Galatea; Scylla and Glaucus.

- Book XIV – Scylla and Glaucus (cont.), the pilgrimage of Aeneas (cont.), the island of Circe, Picus and Canens, the triumph and apotheosis of Aeneas, Pomona and Vertumnus, Messapian shepherd, legends of early Rome, the apotheosis of Romulus.

- Book XV – Numa and the foundation of Crotone, the doctrines of Pythagoras, the death of Numa, Hippolytus, Cipus, Asclepius, the apotheosis of Julius Caesar, epilogue.

Themes

The different genres and divisions in the narrative allow the Metamorphoses to display a wide range of themes. Scholar Stephen M. Wheeler notes that "metamorphosis, mutability, love, violence, artistry, and power are just some of the unifying themes that critics have proposed over the years".

Metamorphosis

In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora;

— Ov., Met., Book I, lines 1–2.

Metamorphosis or transformation is a unifying theme amongst the episodes of the Metamorphoses. Ovid raises its significance explicitly in the opening lines of the poem: In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora; ("I intend to speak of forms changed into new entities;"). Accompanying this theme is often violence, inflicted upon a victim whose transformation becomes part of the natural landscape. This theme amalgamates the much-explored opposition between the hunter and the hunted and the thematic tension between art and nature.

There is a great variety among the types of transformations that take place: from human to inanimate objects (Nileus), constellations (Ariadne's Crown), animals (Perdix); from animals (ants) and fungi (mushrooms) to human; of sex (hyenas); and of colour (pebbles). The metamorphoses themselves are often located metatextually within the poem, through grammatical or narratorial transformations. At other times, transformations are developed into humour or absurdity, such that, slowly, "the reader realizes he is being had", or the very nature of transformation is questioned or subverted. This phenomenon is merely one aspect of Ovid's extensive use of illusion and disguise.

Influence

No work from classical antiquity, either Greek or Roman, has exerted such a continuing and decisive influence on European literature as Ovid's Metamorphoses. The emergence of French, English, and Italian national literatures in the late Middle Ages simply cannot be fully understood without taking into account the effect of this extraordinary poem. ... The only rival we have in our tradition which we can find to match the pervasiveness of the literary influence of the Metamorphoses is perhaps (and I stress perhaps) the Old Testament and the works of Shakespeare.

— Ian Johnston

The Metamorphoses has exerted a considerable influence on literature and the arts, particularly of the West; scholar A. D. Melville says that "It may be doubted whether any poem has had so great an influence on the literature and art of Western civilization as the Metamorphoses." Although a majority of its stories do not originate with Ovid himself, but with such writers as Hesiod and Homer, for others the poem is their sole source.

The influence of the poem on the works of Geoffrey Chaucer is extensive. In The Canterbury Tales, the story of Coronis and Phoebus Apollo (Book II 531–632) is adapted to form the basis for The Manciple's Tale. The story of Midas (Book XI 174–193) is referred to and appears—though much altered—in The Wife of Bath's Tale. The story of Ceyx and Alcyone (from Book IX) is adapted by Chaucer in his poem The Book of the Duchess, written to commemorate the death of Blanche, Duchess of Lancaster and wife of John of Gaunt.

The Metamorphoses was also a considerable influence on William Shakespeare. His Romeo and Juliet is influenced by the story of Pyramus and Thisbe (Metamorphoses Book IV); and, in A Midsummer Night's Dream, a band of amateur actors performs a play about Pyramus and Thisbe. Shakespeare's early erotic poem Venus and Adonis expands on the myth in Book X of the Metamorphoses. In Titus Andronicus, the story of Lavinia's rape is drawn from Tereus' rape of Philomela, and the text of the Metamorphoses is used within the play to enable Titus to interpret his daughter's story. Most of Prospero's renunciative speech in Act V of The Tempest is taken word-for-word from a speech by Medea in Book VII of the Metamorphoses. Among other English writers for whom the Metamorphoses was an inspiration are John Milton—who made use of it in Paradise Lost, considered his magnum opus, and evidently knew it well—and Edmund Spenser. In Italy, the poem was an influence on Giovanni Boccaccio (the story of Pyramus and Thisbe appears in his poem L'Amorosa Fiammetta) and Dante.

During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, mythological subjects were frequently depicted in art. The Metamorphoses was the greatest source of these narratives, such that the term "Ovidian" in this context is synonymous for mythological, in spite of some frequently represented myths not being found in the work. Many of the stories from the Metamorphoses have been the subject of paintings and sculptures, particularly during this period. Some of the most well-known paintings by Titian depict scenes from the poem, including Diana and Callisto, Diana and Actaeon, and Death of Actaeon. These works form part of Titian's "poesie", a collection of seven paintings derived in part from the Metamorphoses, inspired by ancient Greek and Roman mythologies, which were reunited in the Titian exhibition at The National Gallery in 2020. Other famous works inspired by the Metamorphoses include Pieter Brueghel's painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus and Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculpture Apollo and Daphne. The Metamorphoses also permeated the theory of art during the Renaissance and the Baroque style, with its idea of transformation and the relation of the myths of Pygmalion and Narcissus to the role of the artist.

Though Ovid was popular for many centuries, interest in his work began to wane after the Renaissance, and his influence on 19th-century writers was minimal. Towards the end of the 20th century his work began to be appreciated once more. Ted Hughes collected together and retold twenty-four passages from the Metamorphoses in his Tales from Ovid, published in 1997. In 1998, Mary Zimmerman's stage adaptation Metamorphoses premiered at the Lookingglass Theatre, and the following year there was an adaptation of Tales from Ovid by the Royal Shakespeare Company. In the early 21st century, the poem continues to inspire and be retold through books, films and plays. A series of works inspired by Ovid's book through the tragedy of Diana and Actaeon have been produced by French-based collective LFKs and his film/theatre director, writer and visual artist Jean-Michel Bruyere, including the interactive 360° audiovisual installation Si poteris narrare, licet ("if you are able to speak of it, then you may do so") in 2002, 600 shorts and "medium" film from which 22,000 sequences have been used in the 3D 360° audiovisual installation La Dispersion du Fils from 2008 to 2016 as well as an outdoor performance, "Une Brutalité pastorale" (2000).

Manuscript tradition

In spite of the Metamorphoses' enduring popularity from its first publication (around the time of Ovid's exile in 8 AD) no manuscript survives from antiquity. From the 9th and 10th centuries there are only fragments of the poem; it is only from the 11th century onwards that complete manuscripts, of varying value, have been passed down.

The poem retained its popularity throughout late antiquity and the Middle Ages, and is represented by an extremely high number of surviving manuscripts (more than 400); the earliest of these are three fragmentary copies containing portions of Books 1–3, dating to the 9th century.

But the poem's immense popularity in antiquity and the Middle Ages belies the struggle for survival it faced in late antiquity. "A dangerously pagan work," the Metamorphoses was preserved through the Roman period of Christianization, but was criticized by the voices of Augustine and Jerome, who believed the only real metamorphosis was transubstantiation. Though the Metamorphoses did not suffer the ignominious fate of the Medea, no ancient scholia on the poem survive (although they did exist in antiquity), and the earliest complete manuscript is very late, dating from the 11th century.

Influential in the course of the poem's manuscript tradition is the 17th-century Dutch scholar Nikolaes Heinsius. During the years 1640–52, Heinsius collated more than a hundred manuscripts and was informed of many others through correspondence.

Collaborative editorial effort has been investigating the various manuscripts of the Metamorphoses, some forty-five complete texts or substantial fragments, all deriving from a Gallic archetype. The result of several centuries of critical reading is that the poet's meaning is firmly established on the basis of the manuscript tradition or restored by conjecture where the tradition is deficient. There are two modern critical editions: William S. Anderson's, first published in 1977 in the Teubner series, and R. J. Tarrant's, published in 2004 by the Oxford Clarendon Press.

In English translation

The full appearance of the Metamorphoses in English translation (sections had appeared in the works of Chaucer and Gower) coincides with the beginning of printing, and traces a path through the history of publishing. William Caxton produced the first translation of the text on 22 April 1480; set in prose, it is a literal rendering of a French translation known as the Ovide Moralisé.

In 1567, Arthur Golding published a translation of the poem that would become highly influential, the version read by Shakespeare and Spenser. It was written in rhyming couplets of iambic heptameter. The next significant translation was by George Sandys, produced from 1621 to 1626, which set the poem in heroic couplets, a metre that would subsequently become dominant in vernacular English epic and in English translations.

In 1717, a translation appeared from Samuel Garth bringing together work "by the most eminent hands": primarily John Dryden, but several stories by Joseph Addison, one by Alexander Pope, and contributions from Tate, Gay, Congreve, and Rowe, as well as those of eleven others including Garth himself. Translation of the Metamorphoses after this period was comparatively limited in its achievement; the Garth volume continued to be printed into the 1800s, and had "no real rivals throughout the nineteenth century".

Around the later half of the 20th century a greater number of translations appeared as literary translation underwent a revival. This trend has continued into the twenty-first century. In 1994, a collection of translations and responses to the poem, entitled After Ovid: New Metamorphoses, was produced by numerous contributors in emulation of the process of the Garth volume.