Nuclear chemistry is the sub-field of chemistry dealing with radioactivity, nuclear processes, and transformations in the nuclei of atoms, such as nuclear transmutation and nuclear properties.

It is the chemistry of radioactive elements such as the actinides, radium and radon together with the chemistry associated with equipment (such as nuclear reactors) which are designed to perform nuclear processes. This includes the corrosion of surfaces and the behavior under conditions of both normal and abnormal operation (such as during an accident). An important area is the behavior of objects and materials after being placed into a nuclear waste storage or disposal site.

It includes the study of the chemical effects resulting from the absorption of radiation within living animals, plants, and other materials. The radiation chemistry controls much of radiation biology as radiation has an effect on living things at the molecular scale. To explain it another way, the radiation alters the biochemicals within an organism, the alteration of the bio-molecules then changes the chemistry which occurs within the organism; this change in chemistry then can lead to a biological outcome. As a result, nuclear chemistry greatly assists the understanding of medical treatments (such as cancer radiotherapy) and has enabled these treatments to improve.

It includes the study of the production and use of radioactive sources for a range of processes. These include radiotherapy in medical applications; the use of radioactive tracers within industry, science and the environment, and the use of radiation to modify materials such as polymers.

It also includes the study and use of nuclear processes in non-radioactive areas of human activity. For instance, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is commonly used in synthetic organic chemistry and physical chemistry and for structural analysis in macro-molecular chemistry.

History

After Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895, many scientists began to work on ionizing radiation. One of these was Henri Becquerel, who investigated the relationship between phosphorescence and the blackening of photographic plates. When Becquerel (working in France) discovered that, with no external source of energy, the uranium generated rays which could blacken (or fog) the photographic plate, radioactivity was discovered. Marie Skłodowska-Curie (working in Paris) and her husband Pierre Curie isolated two new radioactive elements from uranium ore. They used radiometric methods to identify which stream the radioactivity was in after each chemical separation; they separated the uranium ore into each of the different chemical elements that were known at the time, and measured the radioactivity of each fraction. They then attempted to separate these radioactive fractions further, to isolate a smaller fraction with a higher specific activity (radioactivity divided by mass). In this way, they isolated polonium and radium. It was noticed in about 1901 that high doses of radiation could cause an injury in humans. Henri Becquerel had carried a sample of radium in his pocket and as a result he suffered a highly localized dose which resulted in a radiation burn. This injury resulted in the biological properties of radiation being investigated, which in time resulted in the development of medical treatment.

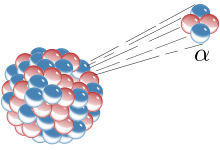

Ernest Rutherford, working in Canada and England, showed that radioactive decay can be described by a simple equation (a linear first degree derivative equation, now called first order kinetics), implying that a given radioactive substance has a characteristic "half-life" (the time taken for the amount of radioactivity present in a source to diminish by half). He also coined the terms alpha, beta and gamma rays, he converted nitrogen into oxygen, and most importantly he supervised the students who conducted the Geiger–Marsden experiment (gold foil experiment) which showed that the 'plum pudding model' of the atom was wrong. In the plum pudding model, proposed by J. J. Thomson in 1904, the atom is composed of electrons surrounded by a 'cloud' of positive charge to balance the electrons' negative charge. To Rutherford, the gold foil experiment implied that the positive charge was confined to a very small nucleus leading first to the Rutherford model, and eventually to the Bohr model of the atom, where the positive nucleus is surrounded by the negative electrons.

In 1934, Marie Curie's daughter (Irène Joliot-Curie) and son-in-law (Frédéric Joliot-Curie) were the first to create artificial radioactivity: they bombarded boron with alpha particles to make the neutron-poor isotope nitrogen-13; this isotope emitted positrons. In addition, they bombarded aluminium and magnesium with neutrons to make new radioisotopes.

In the early 1920s Otto Hahn created a new line of research. Using the "emanation method", which he had recently developed, and the "emanation ability", he founded what became known as "applied radiochemistry" for the researching of general chemical and physical-chemical questions. In 1936 Cornell University Press published a book in English (and later in Russian) titled Applied Radiochemistry, which contained the lectures given by Hahn when he was a visiting professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, in 1933. This important publication had a major influence on almost all nuclear chemists and physicists in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union during the 1930s and 1940s, laying the foundation for modern nuclear chemistry. Hahn and Lise Meitner discovered radioactive isotopes of radium, thorium, protactinium and uranium. He also discovered the phenomena of radioactive recoil and nuclear isomerism, and pioneered rubidium–strontium dating. In 1938, Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann discovered nuclear fission, for which Hahn received the 1944 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. Nuclear fission was the basis for nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons. Hahn is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and godfather of nuclear fission.

Main areas

Radiochemistry is the chemistry of radioactive materials, in which radioactive isotopes of elements are used to study the properties and chemical reactions of non-radioactive isotopes (often within radiochemistry the absence of radioactivity leads to a substance being described as being inactive as the isotopes are stable).

For further details please see the page on radiochemistry.

Radiation chemistry

Radiation chemistry is the study of the chemical effects of radiation on matter; this is very different from radiochemistry as no radioactivity needs to be present in the material which is being chemically changed by the radiation. An example is the conversion of water into hydrogen gas and hydrogen peroxide. Prior to radiation chemistry, it was commonly believed that pure water could not be destroyed.

Initial experiments were focused on understanding the effects of radiation on matter. Using a X-ray generator, Hugo Fricke studied the biological effects of radiation as it became a common treatment option and diagnostic method. Fricke proposed and subsequently proved that the energy from X - rays were able to convert water into activated water, allowing it to react with dissolved species.

Chemistry for nuclear power

Radiochemistry, radiation chemistry and nuclear chemical engineering play a very important role for uranium and thorium fuel precursors synthesis, starting from ores of these elements, fuel fabrication, coolant chemistry, fuel reprocessing, radioactive waste treatment and storage, monitoring of radioactive elements release during reactor operation and radioactive geological storage, etc.

Study of nuclear reactions

A combination of radiochemistry and radiation chemistry is used to study nuclear reactions such as fission and fusion. Some early evidence for nuclear fission was the formation of a short-lived radioisotope of barium which was isolated from neutron irradiated uranium (139Ba, with a half-life of 83 minutes and 140Ba, with a half-life of 12.8 days, are major fission products of uranium). At the time, it was thought that this was a new radium isotope, as it was then standard radiochemical practice to use a barium sulfate carrier precipitate to assist in the isolation of radium. More recently, a combination of radiochemical methods and nuclear physics has been used to try to make new 'superheavy' elements; it is thought that islands of relative stability exist where the nuclides have half-lives of years, thus enabling weighable amounts of the new elements to be isolated. For more details of the original discovery of nuclear fission see the work of Otto Hahn.

The nuclear fuel cycle

This is the chemistry associated with any part of the nuclear fuel cycle, including nuclear reprocessing. The fuel cycle includes all the operations involved in producing fuel, from mining, ore processing and enrichment to fuel production (Front-end of the cycle). It also includes the 'in-pile' behavior (use of the fuel in a reactor) before the back end of the cycle. The back end includes the management of the used nuclear fuel in either a spent fuel pool or dry storage, before it is disposed of into an underground waste store or reprocessed.

Normal and abnormal conditions

The nuclear chemistry associated with the nuclear fuel cycle can be divided into two main areas, one area is concerned with operation under the intended conditions while the other area is concerned with maloperation conditions where some alteration from the normal operating conditions has occurred or (more rarely) an accident is occurring. Without this process, none of this would be true.

Reprocessing

Law

In the United States, it is normal to use fuel once in a power reactor before placing it in a waste store. The long-term plan is currently to place the used civilian reactor fuel in a deep store. This non-reprocessing policy was started in March 1977 because of concerns about nuclear weapons proliferation. President Jimmy Carter issued a Presidential directive which indefinitely suspended the commercial reprocessing and recycling of plutonium in the United States. This directive was likely an attempt by the United States to lead other countries by example, but many other nations continue to reprocess spent nuclear fuels. The Russian government under President Vladimir Putin repealed a law which had banned the import of used nuclear fuel, which makes it possible for Russians to offer a reprocessing service for clients outside Russia (similar to that offered by BNFL).

PUREX chemistry

The current method of choice is to use the PUREX liquid-liquid extraction process which uses a tributyl phosphate/hydrocarbon mixture to extract both uranium and plutonium from nitric acid. This extraction is of the nitrate salts and is classed as being of a solvation mechanism. For example, the extraction of plutonium by an extraction agent (S) in a nitrate medium occurs by the following reaction.

- Pu4+aq + 4NO3−aq + 2Sorganic → [Pu(NO3)4S2]organic

A complex bond is formed between the metal cation, the nitrates and the tributyl phosphate, and a model compound of a dioxouranium(VI) complex with two nitrate anions and two triethyl phosphate ligands has been characterised by X-ray crystallography.

When the nitric acid concentration is high the extraction into the organic phase is favored, and when the nitric acid concentration is low the extraction is reversed (the organic phase is stripped of the metal). It is normal to dissolve the used fuel in nitric acid, after the removal of the insoluble matter the uranium and plutonium are extracted from the highly active liquor. It is normal to then back extract the loaded organic phase to create a medium active liquor which contains mostly uranium and plutonium with only small traces of fission products. This medium active aqueous mixture is then extracted again by tributyl phosphate/hydrocarbon to form a new organic phase, the metal bearing organic phase is then stripped of the metals to form an aqueous mixture of only uranium and plutonium. The two stages of extraction are used to improve the purity of the actinide product, the organic phase used for the first extraction will suffer a far greater dose of radiation. The radiation can degrade the tributyl phosphate into dibutyl hydrogen phosphate. The dibutyl hydrogen phosphate can act as an extraction agent for both the actinides and other metals such as ruthenium. The dibutyl hydrogen phosphate can make the system behave in a more complex manner as it tends to extract metals by an ion exchange mechanism (extraction favoured by low acid concentration), to reduce the effect of the dibutyl hydrogen phosphate it is common for the used organic phase to be washed with sodium carbonate solution to remove the acidic degradation products of the tributyl phosphatioloporus.

New methods being considered for future use

The PUREX process can be modified to make a UREX (URanium EXtraction) process which could be used to save space inside high level nuclear waste disposal sites, such as Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository, by removing the uranium which makes up the vast majority of the mass and volume of used fuel and recycling it as reprocessed uranium.

The UREX process is a PUREX process which has been modified to prevent the plutonium being extracted. This can be done by adding a plutonium reductant before the first metal extraction step. In the UREX process, ~99.9% of the uranium and >95% of technetium are separated from each other and the other fission products and actinides. The key is the addition of acetohydroxamic acid (AHA) to the extraction and scrubs sections of the process. The addition of AHA greatly diminishes the extractability of plutonium and neptunium, providing greater proliferation resistance than with the plutonium extraction stage of the PUREX process.

Adding a second extraction agent, octyl(phenyl)-N,N-dibutyl carbamoylmethyl phosphine oxide (CMPO) in combination with tributylphosphate, (TBP), the PUREX process can be turned into the TRUEX (TRansUranic EXtraction) process this is a process which was invented in the US by Argonne National Laboratory, and is designed to remove the transuranic metals (Am/Cm) from waste. The idea is that by lowering the alpha activity of the waste, the majority of the waste can then be disposed of with greater ease. In common with PUREX this process operates by a solvation mechanism.

As an alternative to TRUEX, an extraction process using a malondiamide has been devised. The DIAMEX (DIAMideEXtraction) process has the advantage of avoiding the formation of organic waste which contains elements other than carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. Such an organic waste can be burned without the formation of acidic gases which could contribute to acid rain. The DIAMEX process is being worked on in Europe by the French CEA. The process is sufficiently mature that an industrial plant could be constructed with the existing knowledge of the process. In common with PUREX this process operates by a solvation mechanism.

Selective Actinide Extraction (SANEX). As part of the management of minor actinides, it has been proposed that the lanthanides and trivalent minor actinides should be removed from the PUREX raffinate by a process such as DIAMEX or TRUEX. In order to allow the actinides such as americium to be either reused in industrial sources or used as fuel the lanthanides must be removed. The lanthanides have large neutron cross sections and hence they would poison a neutron-driven nuclear reaction. To date, the extraction system for the SANEX process has not been defined, but currently, several different research groups are working towards a process. For instance, the French CEA is working on a bis-triazinyl pyridine (BTP) based process.

Other systems such as the dithiophosphinic acids are being worked on by some other workers.

This is the UNiversal EXtraction process which was developed in Russia and the Czech Republic, it is a process designed to remove all of the most troublesome (Sr, Cs and minor actinides) radioisotopes from the raffinates left after the extraction of uranium and plutonium from used nuclear fuel. The chemistry is based upon the interaction of caesium and strontium with poly ethylene oxide (poly ethylene glycol) and a cobalt carborane anion (known as chlorinated cobalt dicarbollide). The actinides are extracted by CMPO, and the diluent is a polar aromatic such as nitrobenzene. Other diluents such as meta-nitrobenzotrifluoride and phenyl trifluoromethyl sulfone have been suggested as well.

Absorption of fission products on surfaces

Another important area of nuclear chemistry is the study of how fission products interact with surfaces; this is thought to control the rate of release and migration of fission products both from waste containers under normal conditions and from power reactors under accident conditions. Like chromate and molybdate, the 99TcO4 anion can react with steel surfaces to form a corrosion resistant layer. In this way, these metaloxo anions act as anodic corrosion inhibitors. The formation of 99TcO2 on steel surfaces is one effect which will retard the release of 99Tc from nuclear waste drums and nuclear equipment which has been lost before decontamination (e.g. submarine reactors lost at sea). This 99TcO2 layer renders the steel surface passive, inhibiting the anodic corrosion reaction. The radioactive nature of technetium makes this corrosion protection impractical in almost all situations. It has also been shown that 99TcO4 anions react to form a layer on the surface of activated carbon (charcoal) or aluminium. A short review of the biochemical properties of a series of key long lived radioisotopes can be read on line.

99Tc in nuclear waste may exist in chemical forms other than the 99TcO4 anion, these other forms have different chemical properties. Similarly, the release of iodine-131 in a serious power reactor accident could be retarded by absorption on metal surfaces within the nuclear plant.

Education

Despite the growing use of nuclear medicine, the potential expansion of nuclear power plants, and worries about protection against nuclear threats and the management of the nuclear waste generated in past decades, the number of students opting to specialize in nuclear and radiochemistry has decreased significantly over the past few decades. Now, with many experts in these fields approaching retirement age, action is needed to avoid a workforce gap in these critical fields, for example by building student interest in these careers, expanding the educational capacity of universities and colleges, and providing more specific on-the-job training.

Nuclear and Radiochemistry (NRC) is mostly being taught at university level, usually first at the Master- and PhD-degree level. In Europe, as substantial effort is being done to harmonize and prepare the NRC education for the industry's and society's future needs. This effort is being coordinated in a project funded by the Coordinated Action supported by the European Atomic Energy Community's 7th Framework Program. Although NucWik is primarily aimed at teachers, anyone interested in nuclear and radiochemistry is welcome and can find a lot of information and material explaining topics related to NRC.

Spinout areas

Some methods first developed within nuclear chemistry and physics have become so widely used within chemistry and other physical sciences that they may be best thought of as separate from normal nuclear chemistry. For example, the isotope effect is used so extensively to investigate chemical mechanisms and the use of cosmogenic isotopes and long-lived unstable isotopes in geology that it is best to consider much of isotopic chemistry as separate from nuclear chemistry.

Kinetics (use within mechanistic chemistry)

The mechanisms of chemical reactions can be investigated by observing how the kinetics of a reaction is changed by making an isotopic modification of a substrate, known as the kinetic isotope effect. This is now a standard method in organic chemistry. Briefly, replacing normal hydrogen (protons) by deuterium within a molecule causes the molecular vibrational frequency of X-H (for example C-H, N-H and O-H) bonds to decrease, which leads to a decrease in vibrational zero-point energy. This can lead to a decrease in the reaction rate if the rate-determining step involves breaking a bond between hydrogen and another atom. Thus, if the reaction changes in rate when protons are replaced by deuteriums, it is reasonable to assume that the breaking of the bond to hydrogen is part of the step which determines the rate.

Uses within geology, biology and forensic science

Cosmogenic isotopes are formed by the interaction of cosmic rays with the nucleus of an atom. These can be used for dating purposes and for use as natural tracers. In addition, by careful measurement of some ratios of stable isotopes it is possible to obtain new insights into the origin of bullets, ages of ice samples, ages of rocks, and the diet of a person can be identified from a hair or other tissue sample. (See Isotope geochemistry and Isotopic signature for further details).

Biology

Within living things, isotopic labels (both radioactive and nonradioactive) can be used to probe how the complex web of reactions which makes up the metabolism of an organism converts one substance to another. For instance a green plant uses light energy to convert water and carbon dioxide into glucose by photosynthesis. If the oxygen in the water is labeled, then the label appears in the oxygen gas formed by the plant and not in the glucose formed in the chloroplasts within the plant cells.

For biochemical and physiological experiments and medical methods, a number of specific isotopes have important applications.

- Stable isotopes have the advantage of not delivering a radiation dose to the system being studied; however, a significant excess of them in the organ or organism might still interfere with its functionality, and the availability of sufficient amounts for whole-animal studies is limited for many isotopes. Measurement is also difficult, and usually requires mass spectrometry to determine how much of the isotope is present in particular compounds, and there is no means of localizing measurements within the cell.

- 2H (deuterium), the stable isotope of hydrogen, is a stable tracer, the concentration of which can be measured by mass spectrometry or NMR. It is incorporated into all cellular structures. Specific deuterated compounds can also be produced.

- 15N, a stable isotope of nitrogen, has also been used. It is incorporated mainly into proteins.

- Radioactive isotopes have the advantages of being detectable in very low quantities, in being easily measured by scintillation counting or other radiochemical methods, and in being localizable to particular regions of a cell, and quantifiable by autoradiography. Many compounds with the radioactive atoms in specific positions can be prepared, and are widely available commercially. In high quantities they require precautions to guard the workers from the effects of radiation—and they can easily contaminate laboratory glassware and other equipment. For some isotopes the half-life is so short that preparation and measurement is difficult.

By organic synthesis it is possible to create a complex molecule with a radioactive label that can be confined to a small area of the molecule. For short-lived isotopes such as 11C, very rapid synthetic methods have been developed to permit the rapid addition of the radioactive isotope to the molecule. For instance a palladium catalysed carbonylation reaction in a microfluidic device has been used to rapidly form amides and it might be possible to use this method to form radioactive imaging agents for PET imaging.

- 3H (tritium), the radioisotope of hydrogen, is available at very high specific activities, and compounds with this isotope in particular positions are easily prepared by standard chemical reactions such as hydrogenation of unsaturated precursors. The isotope emits very soft beta radiation, and can be detected by scintillation counting.

- 11C, carbon-11 is usually produced by cyclotron bombardment of 14N with protons. The resulting nuclear reaction is 14N(p,α)11C. Additionally, carbon-11 can also be made using a cyclotron; boron in the form of boric oxide is reacted with protons in a (p,n) reaction. Another alternative route is to react 10B with deuterons. By rapid organic synthesis, the 11C compound formed in the cyclotron is converted into the imaging agent which is then used for PET.

- 14C, carbon-14 can be made (as above), and it is possible to convert the target material into simple inorganic and organic compounds. In most organic synthesis work it is normal to try to create a product out of two approximately equal sized fragments and to use a convergent route, but when a radioactive label is added, it is normal to try to add the label late in the synthesis in the form of a very small fragment to the molecule to enable the radioactivity to be localised in a single group. Late addition of the label also reduces the number of synthetic stages where radioactive material is used.

- 18F, fluorine-18 can be made by the reaction of neon with deuterons, 20Ne reacts in a (d,4He) reaction. It is normal to use neon gas with a trace of stable fluorine (19F2). The 19F2 acts as a carrier which increases the yield of radioactivity from the cyclotron target by reducing the amount of radioactivity lost by absorption on surfaces. However, this reduction in loss is at the cost of the specific activity of the final product.

Nuclear spectroscopy

Nuclear spectroscopy are methods that use the nucleus to obtain information of the local structure in matter. Important methods are NMR (see below), Mössbauer spectroscopy and Perturbed angular correlation. These methods use the interaction of the hyperfine field with the nucleus' spin. The field can be magnetic or/and electric and are created by the electrons of the atom and its surrounding neighbours. Thus, these methods investigate the local structure in matter, mainly condensed matter in condensed matter physics and solid state chemistry.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

NMR spectroscopy uses the net spin of nuclei in a substance upon energy absorption to identify molecules. This has now become a standard spectroscopic tool within synthetic chemistry. One major use of NMR is to determine the bond connectivity within an organic molecule.

NMR imaging also uses the net spin of nuclei (commonly protons) for imaging. This is widely used for diagnostic purposes in medicine, and can provide detailed images of the inside of a person without inflicting any radiation upon them. In a medical setting, NMR is often known simply as "magnetic resonance" imaging, as the word 'nuclear' has negative connotations for many people.