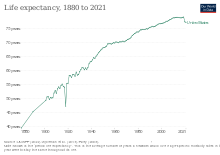

Health may refer to "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity.", according to the World Health Organization (WHO). 78.7 was the average life expectancy for individuals at birth in 2017. The highest cause of death for United States citizens is heart disease. Infectious diseases such as sexually transmitted diseases impact the health of approximately 19 million yearly. The two most commonly reported infectious diseases include chlamydia and gonorrhea. The United States is currently challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic, and is 19th in the world in COVID-19 vaccination rates. All 50 states in the U.S. require immunizations for children in order to enroll in public school, but various exemptions are available by state. Immunizations are often compulsory for military enlistment in the United States.

Most schools within the United States require vaccination, beginning in the 1850s. This became a source of controversy across the country as individuals had opposed the mandate of vaccinations. and became a popular political debate in the following years as schools and locals became more passionate about their cause. Vaccination rates are currently declining in the United States, with one notable measles outbreak stemming from a popular Disneyland park and eventually spreading to 17 states across the United States.

Climate change has been effecting the United States by exacerbating existing health threats and creating new challenges for the healthcare community to face. Air pollution, wild fires, food and waterborne disease, and mental health crisis are all observable effects of climate change.

In the context of ensuring the continuation of medical services, concerns of a current and future shortage of medical doctors due to the supply and demand for physicians in the United States have come from multiple entities including professional bodies such as the American Medical Association (AMA), with the subject being analyzed as well by the American news media in publications such as Forbes, The Nation, and Newsweek. In the 2010s, a study released by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) titled The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034 specifically projected a shortage of between 37,800 and 124,000 individuals within the following two decades, approximately.

Chronic conditions

As of 2003, there are a few programs which aim to gain more knowledge on the epidemiology of chronic disease using data collection. The hope of these programs is to gather epidemiological data on various chronic diseases across the United States and demonstrate how this knowledge can be valuable in addressing chronic disease.

In the United States, as of 2004 nearly one in two Americans (133 million) has at least one chronic medical condition, with most subjects (58%) between the ages of 18 and 64. The number is projected to increase by more than one percent per year by 2030, resulting in an estimated chronically ill population of 171 million. The most common chronic conditions are high blood pressure, arthritis, respiratory diseases like emphysema, and high cholesterol.

Based on data from 2014 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), about 60% of adult Americans were estimated to have one chronic illness, with about 40% having more than one; this rate appears to be mostly unchanged from 2008. MEPS data from 1998 showed 45% of adult Americans had at least one chronic illness, and 21% had more than one.

According to research by the CDC, chronic disease is also especially a concern in the elderly population in America. Chronic diseases like stroke, heart disease, and cancer were among the leading causes of death among Americans aged 65 or older in 2002, accounting for 61% of all deaths among this subset of the population. It is estimated that at least 80% of older Americans are currently living with some form of a chronic condition, with 50% of this population having two or more chronic conditions. The two most common chronic conditions in the elderly are high blood pressure and arthritis, with diabetes, coronary heart disease, and cancer also being reported among the elder population.

In examining the statistics of chronic disease among the living elderly, it is also important to make note of the statistics pertaining to fatalities as a result of chronic disease. Heart disease is the leading cause of death from chronic disease for adults older than 65, followed by cancer, stroke, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases, influenza and pneumonia, and, finally, Alzheimer's disease. Though the rates of chronic disease differ by race for those living with chronic illness, the statistics for leading causes of death among elderly are nearly identical across racial/ethnic groups.

Chronic illnesses cause about 70% of deaths in the US and in 2002 chronic conditions (heart disease, cancers, stroke, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, mental illness and kidney diseases) were six of the top ten causes of mortality in the general US population.Sexually transmitted diseases

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) remain a major public health challenge in the United States. CDC estimates that there are approximately 19 million new STD infections yearly. The country experienced a reduction in reported STDs early in the COVID-19 pandemic, likely due to reduction in care devoted to them, but rates have rebounded in ensuing years. The two most commonly reported infectious diseases with 1.5 million total cases (2009) are chlamydia and gonorrhea. Adolescent girls (15–19 years of age) and young women (20–24 years of age) are especially affected by these two diseases.

Chlamydia

Chlamydia remains the most commonly reported infectious disease in the United States. There were more than 1.2 million cases of chlamydia (1,244,180) reported to CDC in 2009, the largest number of cases ever reported to CDC for any condition. The rate reached 1.6 million cases in 2020, which was actually a decrease from 2016.

Gonorrhea

There were 301,174 reported cases of gonorrhea in 2009 (10 percent less than in 2008), making gonorrhea the second most commonly reported infectious disease in the U.S. In 2009, the gonorrhea rate for women was slightly higher than for men. By 2020, there were more than twice as many cases reported, about 678,000, a 45% increase from 2016.

Syphilis

In 2009, there were 13,997 reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis — the most infectious stages of the disease — the highest number of cases since 1995 and an increase over 2007 (11,466 cases). The number of cases was ten times the 2009 figure by 2020, about 134,000, more than a 50% increase from 2016. According to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 11, 2023, syphilis is now at a rate not seen since the 1950s, increasing by about 30 percent between 2020 and 2021, a big jump from syphilis rates recorded in the early 2000s, where only about 30,000 cases were recorded each year.

Specific outbreaks, plagues, and epidemics in the United States

- 1775–1782 smallpox epidemic

- 1793 yellow fever epidemic

- 1829-1851 cholera pandemic

- 1847 typhus epidemic

- 1863–75 cholera pandemic

- 1900–1904 San Francisco plague

- 1918 flu pandemic

- 1976 Philadelphia legionellosis outbreak

- 1985 salmonellosis outbreak

- 1985 California listeriosis outbreak

- 1998 listeriosis outbreak

- 2006 North American E. coli outbreaks

- 2009 flu pandemic

- 2011 listeriosis outbreak

- 2019 Pacific Northwest measles outbreak

- COVID-19 pandemic

Vaccination

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices makes scientific recommendations which are generally followed by the federal government, state governments, and private health insurance companies.

All 50 states in the U.S. mandate immunizations for children in order to enroll in public school, but various exemptions are available depending on the state. All states have exemptions for people who have medical contraindications to vaccines, and all states except for California, Maine, Mississippi, New York, and West Virginia allow religious exemptions, while sixteen states allow parents to cite personal, conscientious, philosophical, or other objections. An increasing number of parents are using religious and philosophical exemptions; researchers have cited this increased use of exemptions as contributing to loss of herd immunity within these communities, and hence an increasing number of disease outbreaks.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advises physicians to respect the refusal of parents to vaccinate their child after adequate discussion, unless the child is put at significant risk of harm (e.g., during an epidemic, or after a deep and contaminated puncture wound). Under such circumstances, the AAP states that parental refusal of immunization constitutes a form of medical neglect and should be reported to state child protective services agencies.

See Vaccination schedule for the vaccination schedule used in the United States.

Immunizations are often compulsory for military enlistment in the U.S.

All vaccines recommended by the U.S. government for its citizens are required for green card applicants. This requirement stirred controversy when it was applied to the HPV vaccine in July 2008 because of the cost of the vaccine, and because the other thirteen required vaccines prevent diseases which are spread by a respiratory route and are considered highly contagious, while HPV is only spread through sexual contact. In November 2009, this requirement was canceled.

Schools

The United States has a long history of school vaccination requirements. The first school vaccination requirement was enacted in the 1850s in Massachusetts to prevent the spread of smallpox. The school vaccination requirement was put in place after the compulsory school attendance law caused a rapid increase in the number of children in public schools, increasing the risk of smallpox outbreaks. The early movement towards school vaccination laws began at the local level including counties, cities, and boards of education. By 1827, Boston had become the first city to mandate that all children entering public schools show proof of vaccination. In addition, in 1855 the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had established its own statewide vaccination requirements for all students entering school; this influenced other states to implement similar statewide vaccination laws in schools as seen in New York in 1862, Connecticut in 1872, Pennsylvania in 1895, and later the Midwest, South and Western US. By 1963, 20 states had school vaccination laws.

These school vaccination resulted in political debates throughout the United States, as those opposed to vaccination sought to overturn local policies and state laws. An example of this political controversy occurred in 1893 in Chicago, where less than 10 percent of the children were vaccinated despite the twelve-year-old state law. Resistance was seen at the local level of the school district as some local school boards and superintendents opposed the state vaccination laws, leading the state board health inspectors to examine vaccination policies in schools. Resistance proceeded during the mid-1900s and in 1977 a nationwide Childhood Immunization Initiative was developed with the goal of increasing vaccination rates among children to 90% by 1979. During the two-year period of observation, the initiative reviewed the immunization records of more than 28 million children and vaccinated children who had not received the recommended vaccines.

In 1922 the constitutionality of childhood vaccination was examined in the Supreme Court case Zucht v. King. The court decided that a school could deny admission to children who failed to provide a certification of vaccination for the protection of the public health. In 1987, a measles epidemic occurred in Maricopa County, Arizona, and another court case, Maricopa County Health Department vs. Harmon, examined the arguments of an individual's right to education over the state's need to protect against the spread of disease. The court decided that it is prudent to take action to combat the spread of disease by denying un-vaccinated children a place in school until the risk for the spread of measles has passed.

Schools in the United States require an updated immunization record for all incoming and returning students. While all states require an immunization record, this does not mean that all students must get vaccinated. Opt-out criteria are determined at a state level. In the United States, opt-outs take one of three forms: medical, in which a vaccine is contraindicated due to a component ingredient allergy or existing medical condition; religious; and personal philosophical opposition. As of 2019, 46 states allow religious exemptions, with some states requiring proof of religious membership. Only Mississippi, West Virginia, California and New York do not permit religious exemptions. 18 states allow personal or philosophical opposition to vaccination.

Over the last decade vaccination rates have been declining in the United States. Although the rate is fairly limited on a larger scale, vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks are occurring in pockets across the U.S. “In 2012, exemption rates ranged from a low of approximately 0.45 percent in New Mexico, to a high of 6.5 percent in Oregon. The outbreaks have significant correlations with unvaccinated children, and state policy exemption processes. California, which is currently in the process of changing its state exemption policies, dealt with a 2015 measles outbreak stemming from the popular Disneyland park. Significantly, most of the afflicted were unvaccinated, which eventually spread to over 17 separate states across the U.S. If the federal government works to provide an equal vaccination regulation nationally, immunization rates should begin to rise, while preventable outbreaks should diminish.

Old age

In 1790, people over the age of 65 were less than 2% of the American population. In 2017, they were about 14%.

Impact of climate change on health

Climate change continues to affect every country in the world and the United States is no exception. In the U.S. the average temperature has increased between 1.3°F - 1.9°F since record keeping began in 1895, with most of the increase having occurred since about 1970. Additionally, hurricanes and winter storms have increased in both intensity and frequency and the length of the frost-free season has been increasing nationally since the 1980s, affecting ecosystems and agriculture. Climate change and climate variability has many potential effects on the health of Americans. It can exacerbate existing health threats or create new public health challenges through a variety of pathways. It is also important to note that although all Americans will face some health effect from climate change, certain individuals are more vulnerable than others due to levels of exposure, sensitivity, and ability to adapt (See Table).

| Determinant | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure | The degree to which an individual is susceptible to contact with a stressor induced by climate change. | A family in a low-income NYC neighborhood may not be able to afford air conditioning and therefore be more likely to die of heat stroke. |

| Sensitivity | The degree to which the individual could be harmed by the exposure. | A child with asthma is more susceptible to negative health effects from poor air quality than his classmates. |

| Ability to Adapt | The degree to which the individual can adjust and respond to a harmful situation caused by the exposure. | Someone with a physical disability may have a tougher time evacuating during a storm warning. |

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) has identified nine national health topics relating to climate change.

- 1. Air pollution

Ground-level ozone (a key component of smog) is associated with multiple health problems. Examples include diminished lung function, increased hospital admissions and emergency room visits for asthma, and increases in premature deaths. Health-related costs of the current effects of ozone air pollution exceeding national standards have been estimated at $6.5 billion (in 2008 U.S. dollars) nationwide, based on a U.S. assessment of health impacts from ozone levels during 2000–2002.

- 2. Allergens and pollen

Climate change will potentially lead to shifts in precipitation patterns, more frost-free days, warmer seasonal air temperatures, and more carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. These occurrences will lead to both higher pollen concentrations and longer pollen seasons, causing more people to suffer more health effects from pollen and other allergens. In a recent study looking at pollen metrics from 60 metric stations in North America between 1990 and 2018 scientists found that pollen seasons were starting up to 20 days earlier and lasting for up to eight days longer.

- 3. Diseases carried by vectors

Within the United States the impact of climate change from domestically acquiring diseases is uncertain due to vector-control efforts and lifestyle factors, such as time spent indoors, that reduce human-insect contact. However, the impact on the geographical distribution and incidence of vector-borne diseases in other countries where these diseases are already found can still impact Americans, especially due to travel and trade.

- 4. Food and waterborne diarrhea

Diarrheal diseases are more common when temperatures are higher, although location and pathogen can also affect the pattern. Extremely high and low precipitation has also been linked to an increased frequency in the occurrence of diarrheal diseases. Additionally, sporadic increases in stream flow rates, often followed by rapid snowmelt and changes in water treatment, have also been linked outbreaks. Risks of waterborne illness and beach closures resulting from changes in the magnitude of recent precipitation (within the previous 24 hours) and in lake temperature, are expected to increase in the Great Lakes region because of climate change. In the United States, those who are exposed to inadequately or untreated groundwater are most likely to be affected. Additionally, children and the elderly are most vulnerable to serious outcomes.

- 5. Food security

Food production, quality, distribution, and prices can all be affected by climate change. Not only are crops affected by changes in rainfall and extreme weather, but livestock and fish are also being impacted. The related health effects will vary. Due to rising prices, poor persons will turn to “nutrient-poor but calorie-rich foods and/or they endure hunger, with consequences ranging from micronutrient malnutrition to obesity.” Additionally, nutritional quality will be impacted because “elevated atmospheric CO2 is associated with decreased plant nitrogen concentration, and therefore decreased protein, in many crops, such as barley, sorghum, and soy. The nutrient content of crops is also projected to decline if soil nitrogen levels are suboptimal, with reduced levels of nutrients such as calcium, iron, zinc, vitamins, and sugars. This effect can be alleviated if sufficient nitrogen is supplied.”

- 6. Mental health and stress related disorders

Extreme weather and high temperatures can affect mental health in a variety of ways for both individuals with, and without preexisting mental health conditions. Additionally, the symptoms can be short-term or long lasting. For example, studies done after Hurricane Katrina hit the United States Gulf Coast showed that children affected by the hurricane have found high rates of depression, anxiety, behavioral problems and post- traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- 7. Precipitation extremes

The United States has seen an increase in the frequency of heavy precipitation events, and the upward trend is supposed to continue throughout the different regions of the country. These events such as floods and droughts present immediate risks to the health of Americans during the occurrence but can also affect health in the period following the catastrophe. For example, flooding can cause water damage to buildings leading to mold or need for demolition. These events can necessitate the forceful relocation of an entire family which may be distancing them from schools, primary doctors and other resources that they may have gotten used to.

- 8. Temperature extremes

Increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases lead to an increase of both average and extreme temperatures. This is expected to lead to an increase in deaths and illness from heat and a potential decrease in deaths from cold. Days that are hotter than the average seasonal temperature in the summer or colder than the average seasonal temperature in the winter cause increased levels of illness and death by compromising the body’s ability to regulate its temperature or by inducing direct or indirect health complications. Loss of internal temperature control can result in a cascade of illnesses, including heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and hyperthermia in the presence of extreme heat, and hypothermia and frostbite in the presence of extreme cold. Temperature extremes can also worsen chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes-related conditions. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures is associated with increased hospital admissions for cardiovascular, kidney, and respiratory disorders.

- 9. Wildfires

In 2021 we have seen an increase in the news and social media coverage about wildfires spreading throughout California as shown in the image at the end of the section. No doubt, one of the many effects of climate change, these wildfires have many harmful (short and long term) effects on the health of Americans. Not only do many people lose their homes, livelihoods and even lives in these fires, but smoke exposure has many negative effects on physical health as well. It increases respiratory and cardiovascular hospitalizations; emergency department visits; medication dispensations for asthma, bronchitis, chest pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and respiratory infections; and medical visits for lung illnesses.

Impact of poverty on health

Poverty and health are intertwined in the United States. As of 2019, 10.5% of Americans were considered in poverty, according to the U.S. Government's official poverty measure. People who are beneath and at the poverty line have different health risks than citizens above it, as well as different health outcomes. The impoverished population grapples with a plethora of challenges in physical health, mental health, and access to healthcare. These challenges are often due to the population's geographic location and negative environmental effects. Examining the divergences in health between the impoverished and their non-impoverished counterparts provides insight into the living conditions of those who live in poverty.

A 2023 study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that cumulative poverty of 10+ years is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality in the United States, associated with almost 300,000 deaths per year. A single year of poverty was associated with 183,000 deaths in 2019, making it the seventh leading risk factor for mortality that year.