Equal opportunity is a state of fairness in which individuals are treated similarly, unhampered by artificial barriers, prejudices, or preferences, except when particular distinctions can be explicitly justified. For example, the intent of equal employment opportunity is that the important jobs in an organization should go to the people who are most qualified – persons most likely to perform ably in a given task – and not go to persons for reasons deemed arbitrary or irrelevant, such as circumstances of birth, upbringing, having well-connected relatives or friends, religion, sex, ethnicity, race, caste, or involuntary personal attributes such as disability, age.

According to proponents of the concept, chances for advancement should be open to everybody without regard for wealth, status, or membership in a privileged group. The idea is to remove arbitrariness from the selection process and base it on some "pre-agreed basis of fairness, with the assessment process being related to the type of position" and emphasizing procedural and legal means. Individuals should succeed or fail based on their efforts and not extraneous circumstances such as having well-connected parents. It is opposed to nepotism and plays a role in whether a social structure is seen as legitimate. The concept is applicable in areas of public life in which benefits are earned and received such as employment and education, although it can apply to many other areas as well. Equal opportunity is central to the concept of meritocracy.

Differing political viewpoints

People with differing political viewpoints often view the concept differently. The meaning of equal opportunity is debated in fields such as political philosophy, sociology and psychology. It is being applied to increasingly wider areas beyond employment, including lending, housing, college admissions, voting rights, and elsewhere. In the classical sense, equality of opportunity is closely aligned with the concept of equality before the law and ideas of meritocracy.

Generally, the terms equality of opportunity and equal opportunity are interchangeable, with occasional slight variations; the former has more of a sense of being an abstract political concept while "equal opportunity" is sometimes used as an adjective, usually in the context of employment regulations, to identify an employer, a hiring approach, or the law. Equal opportunity provisions have been written into regulations and have been debated in courtrooms. It is sometimes conceived as a legal right against discrimination. It is an ideal which has become increasingly widespread in Western nations during the last several centuries and is intertwined with social mobility, most often with upward mobility and with rags to riches stories:

The coming President of France is the grandson of a shoemaker. The actual President is a peasant's son. His predecessor again humbly began life in the shipping business. There is surely equality of opportunity under the new order in the old nation.

Theory

Outline of the concept

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the concept assumes that society is stratified with a diverse range of roles, some of which are more desirable than others. The benefit of equality of opportunity is to bring fairness to the selection process for coveted roles in corporations, associations, nonprofits, universities and elsewhere. According to one view, there is no "formal linking" between equality of opportunity and political structure, in the sense that there can be equality of opportunity in democracies, autocracies and in communist nations, although it is primarily associated with a competitive market economy and embedded within the legal frameworks of democratic societies. People with different political perspectives see equality of opportunity differently: liberals disagree about which conditions are needed to ensure it and many "old-style" conservatives see inequality and hierarchy in general as beneficial out of a respect for tradition. It can apply to a specific hiring decision, or to all hiring decisions by a specific company, or rules governing hiring decisions for an entire nation. The scope of equal opportunity has expanded to cover more than issues regarding the rights of minority groups, but covers practices regarding "recruitment, hiring, training, layoffs, discharge, recall, promotions, responsibility, wages, sick leave, vacation, overtime, insurance, retirement, pensions, and various other benefits".

The concept has been applied to numerous aspects of public life, including accessibility of polling stations, care provided to HIV patients, whether men and women have equal opportunities to travel on a spaceship, bilingual education, skin color of models in Brazil, television time for political candidates, army promotions, admittance to universities and ethnicity in the United States. The term is interrelated with and often contrasted with other conceptions of equality such as equality of outcome and equality of autonomy. Equal opportunity emphasizes the personal ambition and talent and abilities of the individual, rather than his or her qualities based on membership in a group, such as a social class or race or extended family. Further, it is seen as unfair if external factors that are viewed as being beyond the control of a person significantly influence what happens to him or her. Equal opportunity then emphasizes a fair process whereas in contrast equality of outcome emphasizes a fair outcome. In sociological analysis, equal opportunity is seen as a factor correlating positively with social mobility, in the sense that it can benefit society overall by maximizing well-being.

Different types

There are different concepts lumped under equality of opportunity.

Formal equality of opportunity is a lack of (unfair) direct discrimination. It requires that deliberate discrimination be relevant and meritocratic. For instance, job interviews should only discriminate against applicants for job incompetence. Universities should not accept a less-capable applicant instead of a more-capable applicant who can't pay tuition.

Substantive equality of opportunity is absence of indirect discrimination. It requires that society be fair and meritocratic. For instance, a person should not be more likely to die at work because they were born in a country with corrupt labor law enforcement. No one should have to drop out of school because their family needs of a full-time carer or wage earner.

Formal equality of opportunity does not imply substantive equality of opportunity. Firing any employee who gets pregnant is formally equal, but substantively it hurts women more.

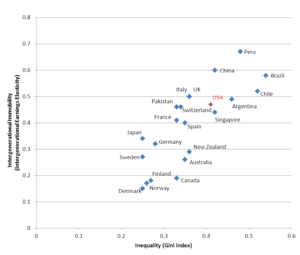

Substantive inequality is often more difficult to address. A political party that formally allows anyone to join, but meets in a non-wheelchair-accessible building far from public transit, substantively discriminates against both young and old members as they are less likely to be able-bodied car-owners. However, if the party raises membership dues in order to afford a better building, it discourages poor members instead. A workplace in which it is difficult for persons with special needs and disabilities to perform can considered as a type of substantive inequality, although job restructuring activities can be done to make it easier for disabled persons to succeed. Grade-cutoff university admission is formally fair, but if in practice it overwhelmingly picks women and graduates of expensive user-fee schools, it is substantively unfair to men and the poor. The unfairness has already taken place and the university can choose to try to counterbalance it, but it likely can not single-handedly make pre-university opportunities equal. Social mobility and the Great Gatsby curve are often used as an indicator of substantive equality of opportunity.

Both equality concepts say that it is unfair and inefficient if extraneous factors rule people's lives. Both accept as fair inequality based on relevant, meritocratic factors. They differ in the scope of the methods used to promote them.

Formal equality of opportunity

Formal equality of opportunity is sometimes referred to as the nondiscrimination principle or described as the absence of direct discrimination, or described in the narrow sense as equality of access. It is characterized by:

- Open call. Positions bringing superior advantages should be open to all applicants and job openings should be publicized in advance giving applicants a "reasonable opportunity" to apply. Further, all applications should be accepted.

- Fair judging. Applications should be judged on their merits, with procedures designed to identify those best-qualified. The evaluation of the applicant should be in accord with the duties of the position and for the job opening of choir director, for example, the evaluation may judge applicants based on musical knowledge rather than some arbitrary criterion such as hair color.

- An application is chosen. The applicant judged as "most qualified" is offered the position while others are not. There is agreement that the result of the process is again unequal, in the sense that one person has the position while another does not, but that this outcome is deemed fair on procedural grounds.

The formal approach is seen as a somewhat basic "no frills" or "narrow" approach to equality of opportunity, a minimal standard of sorts, limited to the public sphere as opposed to private areas such as the family, marriage, or religion. What is considered "fair" and "unfair" is spelled out in advance. An expression of this version appeared in The New York Times: "There should be an equal opportunity for all. Each and every person should have as great or as small an opportunity as the next one. There should not be the unfair, unequal, superior opportunity of one individual over another."

This sense was also expressed by economists Milton and Rose Friedman in their 1980 book Free to Choose. The Friedmans explained that equality of opportunity was "not to be interpreted literally" since some children are born blind while others are born sighted, but that "its real meaning is ... a career open to the talents". This means that there should be "no arbitrary obstacles" blocking a person from realizing their ambitions: "Not birth, nationality, color, religion, sex, nor any other irrelevant characteristic should determine the opportunities that are open to a person – only his abilities".

A somewhat different view was expressed by John Roemer, who used the term nondiscrimination principle to mean that "all individuals who possess the attributes relevant for the performance of the duties of the position in question be included in the pool of eligible candidates, and that an individual's possible occupancy of the position be judged only with respect to those relevant attributes". Matt Cavanagh argued that race and sex should not matter when getting a job, but that the sense of equality of opportunity should not extend much further than preventing straightforward discrimination.

It is a relatively straightforward task for legislators to ban blatant efforts to favor one group over another and encourage equality of opportunity as a result. Japan banned gender-specific job descriptions in advertising as well as sexual discrimination in employment as well as other practices deemed unfair, although a subsequent report suggested that the law was having minimal effect in securing Japanese women high positions in management. In the United States, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission sued a private test preparation firm, Kaplan, for unfairly using credit histories to discriminate against African Americans in terms of hiring decisions. According to one analysis, it is possible to imagine a democracy which meets the formal criteria (1 through 3), but which still favors wealthy candidates who are selected in free and fair elections.

Substantive equality of opportunity

If higher inequality makes intergenerational mobility more difficult, it is likely because opportunities for economic advancement are more unequally distributed among children.

Substantive equality of opportunity, sometimes called fair equality of opportunity, is a somewhat broader and more expansive concept than the more limiting formal equality of opportunity and it deals with what is sometimes described as indirect discrimination. It goes farther and is more controversial than the formal variant; and has been thought to be much harder to achieve, with greater disagreement about how to achieve greater equality; and has been described as "unstable", particularly if the society in question is unequal to begin with in terms of great disparity of wealth. It has been identified as more of a left-leaning political position, but this is not a hard-and-fast rule. The substantive model is advocated by people who see limitations in the formal model:

Therein lies the problem with the idea of equal opportunity for all. Some people are simply better placed to take advantage of opportunity.

— Deborah Orr in The Guardian, 2009

There is little income mobility – the notion of America as a land of opportunity is a myth.

— Joseph E. Stiglitz, 2012

In the substantive approach, the starting point before the race begins is unfair since people have had differing experiences before even approaching the competition. The substantive approach examines the applicants themselves before applying for a position and judges whether they have equal abilities or talents; and if not, then it suggests that authorities (usually the government) take steps to make applicants more equal before they get to the point where they compete for a position and fixing the before-the-starting-point issues has sometimes been described as working towards "fair access to qualifications". It seeks to remedy inequalities perhaps because of an "unfair disadvantage" based sometimes on "prejudice in the past".

According to John Hills, children of wealthy and well-connected parents usually have a decisive advantage over other types of children and he notes that "advantage and disadvantage reinforce themselves over the life cycle, and often on to the next generation" so that successful parents pass along their wealth and education to succeeding generations, making it difficult for others to climb up a social ladder. However, so-called positive action efforts to bring an underprivileged person up to speed before a competition begins are limited to the period of time before the evaluation begins. At that point, the "final selection for posts must be made according to the principle the best person for the job", that is, a less qualified applicant should not be chosen over a more qualified applicant. There are also nuanced views too: one position suggested that the unequal results following a competition were unjust if caused by bad luck, but just if chosen by the individual and that weighing matters such as personal responsibility was important. This variant of the substantive model has sometimes been called luck egalitarianism. Regardless of the nuances, the overall idea is still to give children from less fortunate backgrounds more of a chance, or to achieve at the beginning what some theorists call equality of condition. Writer Ha-Joon Chang expressed this view:

We can accept the outcome of a competitive process as fair only when the participants have equality in basic capabilities; the fact that no one is allowed to have a head start does not make the race fair if some contestants have only one leg.

In a sense, substantive equality of opportunity moves the "starting point" further back in time. Sometimes it entails the use of affirmative action policies to help all contenders become equal before they get to the starting point, perhaps with greater training, or sometimes redistributing resources via restitution or taxation to make the contenders more equal. It holds that all who have a "genuine opportunity to become qualified" be given a chance to do so and it is sometimes based on a recognition that unfairness exists, hindering social mobility, combined with a sense that the unfairness should not exist or should be lessened in some manner. One example postulated was that a warrior society could provide special nutritional supplements to poor children, offer scholarships to military academies and dispatch "warrior skills coaches" to every village as a way to make opportunity substantively more fair. The idea is to give every ambitious and talented youth a chance to compete for prize positions regardless of their circumstances of birth.

The substantive approach tends to have a broader definition of extraneous circumstances which should be kept out of a hiring decision. One editorial writer suggested that among the many types of extraneous circumstances which should be kept out of hiring decisions was personal beauty, sometimes termed "lookism":

Lookism judges individuals by their physical allure rather than abilities or merit. This naturally works to the advantage of people perceived to rank higher in the looks department. They get preferential treatment at the cost of others. Which fair, democratic system can justify this? If anything, lookism is as insidious as any other form of bias based on caste, creed, gender and race that society buys into. It goes against the principle of equality of opportunity.

The substantive position was advocated by Bhikhu Parekh in 2000 in Rethinking Multiculturalism, in which he wrote that "all citizens should enjoy equal opportunities to acquire the capacities and skills needed to function in society and to pursue their self-chosen goals equally effectively" and that "equalising measures are justified on grounds of justice as well as social integration and harmony". Parekh argued that equal opportunities included so-called cultural rights which are "ensured by the politics of recognition".

Affirmative action programs usually fall under the substantive category. The idea is to help disadvantaged groups get back to a normal starting position after a long period of discrimination. The programs involve government action, sometimes with resources being transferred from an advantaged group to a disadvantaged one and these programs have been justified on the grounds that imposing quotas counterbalances the past discrimination as well as being a "compelling state interest" in diversity in society. For example, there was a case in São Paulo in Brazil of a quota imposed on the São Paulo Fashion Week to require that "at least 10 percent of the models to be black or indigenous" as a coercive measure to counteract a "longstanding bias towards white models". It does not have to be accomplished via government action: for example, in the 1980s in the United States, President Ronald Reagan dismantled parts of affirmative action, but one report in the Chicago Tribune suggested that companies remained committed to the principle of equal opportunity regardless of government requirements. In another instance, upper-middle-class students taking the Scholastic Aptitude Test in the United States performed better since they had had more "economic and educational resources to prepare for these test than others". The test itself was seen as fair in a formal sense, but the overall result was seen as nevertheless unfair. In India, the Indian Institutes of Technology found that to achieve substantive equality of opportunity the school had to reserve 22.5 percent of seats for applicants from "historically disadvantaged schedule castes and tribes". Elite universities in France began a special "entrance program" to help applicants from "impoverished suburbs".

Equality of fair opportunity

Philosopher John Rawls offered this variant of substantive equality of opportunity and explained that it happens when individuals with the same "native talent and the same ambition" have the same prospects of success in competitions. Gordon Marshall offers a similar view with the words "positions are to be open to all under conditions in which persons of similar abilities have equal access to office". An example was given that if two persons X and Y have identical talent, but X is from a poor family while Y is from a rich one, then equality of fair opportunity is in effect when both X and Y have the same chance of winning the job. It suggests the ideal society is "classless" without a social hierarchy being passed from generation to generation, although parents can still pass along advantages to their children by genetics and socialization skills. One view suggests that this approach might advocate "invasive interference in family life". Marshall posed this question:

Does it demand that, however unequal their abilities, people should be equally empowered to achieve their goals? This would imply that the unmusical individual who wants to be a concert pianist should receive more training than the child prodigy.

Economist Paul Krugman agrees mostly with the Rawlsian approach in that he would like to "create the society each of us would want if we didn't know in advance who we'd be". Krugman elaborated: "If you admit that life is unfair, and that there's only so much you can do about that at the starting line, then you can try to ameliorate the consequences of that unfairness".

Level playing field

Some theorists have posed a level playing field conception of equality of opportunity, similar in many respects to the substantive principle (although it has been used in different contexts to describe formal equality of opportunity) and it is a core idea regarding the subject of distributive justice espoused by John Roemer and Ronald Dworkin and others. Like the substantive notion, the level playing field conception goes farther than the usual formal approach. The idea is that initial "unchosen inequalities" – prior circumstances over which an individual had no control, but which impact his or her success in a given competition for a particular post – these unchosen inequalities should be eliminated as much as possible, according to this conception. According to Roemer, society should "do what it can to level the playing field so that all those with relevant potential will eventually be admissible to pools of candidates competing for positions". Afterwards, when an individual competes for a specific post, he or she might make specific choices which cause future inequalities – and these inequalities are deemed acceptable because of the previous presumption of fairness. This system helps undergird the legitimacy of a society's divvying up of roles as a result in the sense that it makes certain achieved inequalities "morally acceptable", according to persons who advocate this approach. This conception has been contrasted to the substantive version among some thinkers and it usually has ramifications for how society treats young persons in such areas as education and socialization and health care, but this conception has been criticized as well. John Rawls postulated the difference principle which argued that "inequalities are justified only if needed to improve the lot of the worst off, for example by giving the talented an incentive to create wealth".

Meritocracy

There is some overlap among these different conceptions with the term meritocracy which describes an administrative system which rewards such factors as individual intelligence, credentials, education, morality, knowledge or other criteria believed to confer merit. Equality of opportunity is often seen as a major aspect of a meritocracy. One view was that equality of opportunity was more focused on what happens before the race begins while meritocracy is more focused on fairness at the competition stage. The term meritocracy can also be used in a negative sense to refer to a system in which an elite hold themselves in power by controlling access to merit (via access to education, experience, or bias in assessment or judgment).

Moral senses

There is general agreement that equality of opportunity is good for society, although there are diverse views about how it is good since it is a value judgement. It is generally viewed as a positive political ideal in the abstract sense. In nations where equality of opportunity is absent, it can negatively impact economic growth, according to some views and one report in Al Jazeera suggested that Egypt, Tunisia and other Middle Eastern nations were stagnating economically in part because of a dearth of equal opportunity. The principle of equal opportunity can conflict with notions of meritocracy in circumstances in which individual differences in human abilities are believed to be determined mostly by genetics as in such circumstances there can be conflict about how to achieve fairness in such situations.

Practical considerations

Difficulties with implementation

There is general agreement that programs to bring about certain types of equality of opportunity can be difficult and that efforts to cause one result often have unintended consequences or cause other problems. There is agreement that the formal approach is easier to implement than the others, although there are difficulties there too.

A government policy that requires equal treatment can pose problems for lawmakers. A requirement for the government to provide equal health care services for all citizens can be prohibitively expensive. If the government seeks equality of opportunity for citizens to get health care by rationing services using a maximization model to try to save money, new difficulties might emerge. For example, trying to ration health care by maximizing the "quality-adjusted years of life" might steer monies away from disabled persons even though they may be more deserving, according to one analysis. In another instance, BBC News questioned whether it was wise to ask female army recruits to undergo the same strenuous tests as their male counterparts since many women were being injured as a result.

Age discrimination can present vexing challenges for policymakers trying to implement equal opportunity. According to several studies, attempts to be equally fair to both a young and an old person are problematic because the older person has presumably fewer years left to live and it may make more sense for a society to invest greater resources in a younger person's health. Treating both persons equally while following the letter of the equality of opportunity seems unfair from a different perspective.

Efforts to achieve equal opportunity along one dimension can exacerbate unfairness in other dimensions. For example, public bathrooms: If for the sake of fairness the physical area of men's and women's bathrooms is equal, the overall result may be unfair since men can use urinals, which require less physical space. In other words, a more fair arrangement may be to allot more physical space for women's restrooms. The sociologist Harvey Molotch explained: "By creating men's and women's rooms of the same size, society guarantees that individual women will be worse off than individual men."

Another difficulty is that it is hard for a society to bring substantive equality of opportunity to every type of position or industry. If a nation focuses efforts on some industries or positions, then people with other talents may be left out. For example, in an example in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, a warrior society might provide equal opportunity for all kinds of people to achieve military success through fair competition, but people with non-military skills such as farming may be left out.

Lawmakers have run into problems trying to implement equality of opportunity. In 2010 in Britain, a legal requirement "forcing public bodies to try to reduce inequalities caused by class disadvantage" was scrapped after much debate and replaced by a hope that organizations would try to focus more on "fairness" than "equality" as fairness is generally seen as a much unclear concept than equality, but easier for politicians to manage if they are seeking to avoid fractious debate. In New York City, mayor Ed Koch tried to find ways to maintain the "principle of equal treatment" while arguing against more substantive and abrupt transfer payments called minority set-asides.

Many countries have specific bodies tasked with looking at equality of opportunity issues. In the United States, for example, it is the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission; in Britain, there is the Equality of Opportunity Committee as well as the Equality and Human Rights Commission; in Canada, the Royal Commission on the Status of Women has "equal opportunity as its precept"; and in China, the Equal Opportunities Commission handles matters regarding ethnic prejudice. In addition, there have been political movements pushing for equal treatment, such as the Women's Equal Opportunity League which in the early decades of the twentieth century, pushed for fair treatment by employers in the United States. One of the group's members explained:

I am not asking for sympathy but for an equal right with men to earn my own living in the best way open and under the most favorable conditions that I could choose for myself.

Global initiatives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 and Goal 10 are also aimed at ensuring equal opportunities for women at all levels of decision making, and reducing inequalities of outcome.

Difficulties with measurement

The consensus view is that trying to measure equality of opportunity is difficult whether examining a single hiring decision or looking at groups over time.

- Single instance. It is possible to reexamine the procedures governing a specific hiring decision, see if they were followed, and re-evaluate the selection by asking questions such as "Was it fair? Were fair procedures followed? Was the best applicant selected?". This is a judgment call and biases may enter into the minds of decision-makers. The determination of equality of opportunity in such an instance is based on mathematical probability: if equality of opportunity is in effect, then it is seen as fair if each of two applicants has a 50 percent chance of winning the job, that is, they both have equal chances to succeed (assuming of course that the person making the probability assessment is unaware of all variables – including valid ones such as talent or skill as well as arbitrary ones such as race or gender). However, it is hard to measure whether each applicant had a 50 percent chance based on the outcome.

- Groups. When assessing the equal opportunity for a type of job or company or industry or nation, then statistical analysis is often done by looking at patterns and abnormalities, typically comparing subgroups with larger groups on a percentage basis. If equality of opportunity is violated, perhaps by discrimination which affects a subgroup or population over time, it is possible to make this determination using statistical analysis, but there are numerous difficulties involved. Nevertheless, entities such as city governments and universities have hired full-time professionals with knowledge of statistics to ensure compliance with equal opportunity regulations. For example, Colorado State University requires the director of its Office of Equal Opportunity to maintain extensive statistics on its employees by job category as well as minorities and gender. In Britain, Aberystwyth University collects information including the "representation of women, men, members of racial or ethnic minorities and people with disabilities amongst applicants for posts, candidates interviewed, new appointments, current staff, promotions and holders of discretionary awards" to comply with equal opportunity laws.

It is difficult to prove unequal treatment although statistical analysis can provide indications of problems, it is subject to conflicts over interpretation and methodological issues. For example, a study in 2007 by the University of Washington examined its treatment of women. Researchers collected statistics about female participation in numerous aspects of university life, including percentages of women with full professorships (23 percent), enrollment in programs such as nursing (90 pperpercentd engineerings (18 percent). There is wide variation in how these statistics might be interpreted. For example, the 23 percent figure for women with full professorships could be compared to the total population of women (presumably 50 percent) perhaps using census data, or it might be compared to the percentage of women with full professorships at competing universities. It might be used in an analysis of how many women applied for the position of full professor compared to how many women attained this position. Further, the 23 percent figure could be used as a benchmark or baseline figure as part of an ongoing longitudinal analysis to be compared with future surveys to track progress over time. In addition, the strength of the conclusions is subject to statistical issues such as sample size and bias. For reasons such as these, there is considerable difficulty with most forms of statistical interpretation.

Statistical analysis of equal opportunity has been done using sophisticated examinations of computer databases. An analysis in 2011 by University of Chicago researcher Stefano Allesina examined 61,000 names of Italian professors by looking at the "frequency of last names", doing one million random drawings and he suggested that Italian academia was characterized by violations of equal opportunity practices as a result of these investigations. The last names of Italian professors tended to be similar more often than predicted by random chance. The study suggested that newspaper accounts showing that "nine relatives from three generations of a single-family (were) on the economics faculty" at the University of Bari were not aberrations, but indicated a pattern of nepotism throughout Italian academia.

There is support for the view that often equality of opportunity is measured by the criteria of equality of outcome, although with difficulty. In one example, an analysis of relative equality of opportunity was done based on outcomes, such as a case to see whether hiring decisions were fair regarding men versus women – the analysis was done using statistics based on average salaries for different groups. In another instance, a cross-sectional statistical analysis was conducted to see whether social class affected participation in the United States Armed Forces during the Vietnam War: a report in Time by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggested that soldiers came from a variety of social classes and that the principle of equal opportunity had worked, possibly because soldiers had been chosen by a lottery process for conscription. In college admissions, equality of outcome can be measured directly by comparing offers of admission given to different groups of applicants: for example, there have been reports in newspapers of discrimination against Asian Americans regarding college admissions in the United States which suggest that Asian American applicants need higher grades and test scores to win admission to prestigious universities than other ethnic groups.

Marketplace considerations

Equal opportunity has been described as a fundamental basic notion in business and commerce and described by economist Adam Smith as a basic economic precept. There has beeresearchng suggesting that "competitive markets will tend to drive out such discrimination" since employers or institutions which hire based on arbitrary criteria will be weaker as a result and not perform as well as firms that embrace equality of opportunity. Firms competing for overseas contracts have sometimes argued in the press for equal chances during the bidding process, such as when American oil corporations wanted equal shots at developing oil fields in Sumatra; and firms, seeing how fairness is beneficial while competing for contracts, can apply the lesson to other areas such as internal hiring and promotion decisions. A report in USA Today suggested that the goal of equal opportunity was "being achieved throughout most of the business and government labor markets because major employers pay based on potential and actual productivity".

Fair opportunity practices include measures taken by an organization to ensure efficiency effectiveness and fairness in the employment process. A basic definition of equality is the idea of equal treatment and respect. In job advertisements and descriptions, the fact that the employer is an equal opportunity employer is sometimes indicated by the abbreviations EOE or MFDV, which stands for Minority, Female, Disabled, Veteran. Analyst Ross Douthat in The New York Times suggested that equality of opportunity depends on a rising economy which brings new chances for upward mobility and he suggested that greater equality of opportunity is more easily achieved during "times of plenty". Efforts to achieve equal opportunity can rise and recede, sometimes as a result of economic conditions or political choices. Empirical evidence from public health research also suggests that equality of opportunity is linked to better health outcomes in the United States and Europe.

History

According to professor David Christian of Macquarie University, an underlying Big History trend has been a shift from seeing people as resources to exploiting towards a perspective of seeing people as individuals to empower. According to Christian, in many ancient agrarian civilizations, roughly nine of every ten persons was a peasant exploited by a ruling class. In the past thousand years, there has been a gradual movement in the direction of greater respect for equal opportunity as political structures based on generational hierarchies and feudalism broke down during the late Middle Ages and new structures emerged during the Renaissance. Monarchies were replaced by democracies: kings were replaced by parliaments and congresses. Slavery was also abolished generally. The new entity of the nation state emerged with highly specialized parts, including corporations, laws, and new ideas about citizenship as well as values about individual rights found expression in constitutions, laws, and statutes.

In the United States, one legal analyst suggested that the real beginning of the modern sense of equal opportunity was in the Fourteenth Amendment which provided "equal protection under the law". The amendment did not mention equal opportunity directly, but it helped undergird a series of later rulings which dealt with legal struggles, particularly by African Americans and later women, seeking greater political and economic power in the growing republic. In 1933, a congressional "Unemployment Relief Act" forbade discrimination "based on race, color, or creed". The Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision furthered government initiatives to end discrimination.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 10925 which enabled a presidential committee on an equal opportunity, which was soon followed by President Lyndon B. Johnson's Executive Order 11246. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 became the legal underpinning of equal opportunity in employment. Businesses and other organizations learned to comply with the rulings by specifying fair hiring and promoting practices and posting these policy notices on bulletin boards, employee handbooks, and manuals as well ain s training sessions and films. Courts dealt with issues about equal opportunities, such as the 1989 Wards Cove decision, the Supreme Court ruled that statistical evidence by itself was insufficient to prove racial discrimination. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was established, sometimes reviewing charges of discrimination cases which numbered in the tens of thousands annually during the 1990s. Some law practices specialized in employment law. The conflict between formal and substantive approaches manifested itself in backlashes, sometimes described as reverse discrimination, such as the Bakke case when a white male applicant to medical school sued based on being denied admission because of a quota system preferring minority applicants. In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act prohibited discrimination against disabled persons, including cases of equal opportunity. In 2008, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act prevents employers from using genetic information when hiring, firing, or promoting employees.

Measures

Many economists measure the degree of equal opportunity with measures of economic mobility. For instance, Joseph Stiglitz asserts that with five economic divisions and full equality of opportunity, "20 percent of those in the bottom fifth would see their children in the bottom fifth. Denmark almost achieves that – 25 percent are stuck there. Britain, supposedly notorious for its class divisions, does only a little worse (30 percent). That means they have a 70 percent chance of moving up. The chances of moving up in America, though, are markedly smaller (only 58 percent of children born to the bottom group make it out), and when they do move up, they tend to move up only a little". Similar analyses can be performed for each economic division and overall. They all show how far from the ideal all industrialized nations are and how correlated measures of equal opportunity are with income inequality and wealth inequality. Equal opportunity has ramifications beyond income; the American Human Development Index, rooted in the capabilities approach pioneered by Amartya Sen, is used to measure opportunity across geographies in the U.S. using health, education, and standard of living outcomes.

Criticism

There is agreement that the concept of equal opportunity lacks a precise definition. While it generally describes "open and fair competition" with equal chances for achieving sought-after jobs or positions as well as an absence of discrimination, the concept is elusive with a "wide range of meanings". It is hard to measure, and implementation poses problems as well as disagreements about what to do.

There have been various criticisms directed at both the substantive and formal approaches. One account suggests that left-leaning thinkers who advocate equality of outcome fault even formal equality of opportunity because it "legitimates inequalities of wealth and income". John W. Gardner suggested several views: (1) that inequalities will always exist regardless of trying to erase them; (2) that bringing everyone "fairly to the starting line" without dealing with the "destructive competitiveness that follows"; (3) any equalities achieved will entail future inequalities. Substantive equality of opportunity has led to concerns that efforts to improve fairness "ultimately collapses into the different one of equality of outcome or condition".

Economist Larry Summers advocated an approach of focusing on equality of opportunity and not equality of outcomes and that the way to strengthen equal opportunity was to bolster public education. A contrasting report in The Economist criticized efforts to contrast equality of opportunity and equality of outcome as being opposite poles on a hypothetical ethical scale, such that equality of opportunity should be the "highest ideal" while equality of outcome was "evil". Rather, the report argued that any difference between the two types of equality was illusory and that both terms were highly interconnected. According to this argument, wealthier people have greater opportunities – wealth itself can be considered as "distilled opportunity" – and children of wealthier parents have access to better schools, health care, nutrition and so forth. Accordingly, people who endorse equality of opportunity may like the idea of it in principle, yet at the same time, they would be unwilling to take the extreme steps or "titanic interventions" necessary to achieve real intergenerational equality. A slightly different view in The Guardian suggested that equality of opportunity was merely a "buzzword" to sidestep the thornier political question of income inequality.

There is speculation that since equality of opportunity is only one of sometimes competing "justice norms", there is a risk that following equality of opportunity too strictly might cause problems in other areas. A hypothetical example was suggested: suppose wealthier people gave excessive amounts of campaign contributions; suppose further that these contributions resulted in better regulations, and then laws limiting such contributions based on equal opportunity for all political participants may have the unintended long term consequence of making political decision-making lackluster and possibly hurting the groups that it was trying to protect. Philosopher John Kekes makes a similar point in his book The Art of Politics in which he suggests that there is a danger to elevating any one particular political good – including equality of opportunity – without balancing competing goods such as justice, property rights and others. Kekes advocated having a balanced perspective, including a continuing dialog between cautionary elements and reform elements. A similar view was expressed by Ronald Dworkin in The Economist:

It strikes us as wrong – or not right – that some people starve while others have private jets. We are uncomfortable when university professors earn less, for example than junior lawyers. But equality appears to pull against other important ideals such as liberty and efficiency.

Economist Paul Krugman sees equality of opportunity as a "non-Utopian compromise" which works and is a "pretty decent arrangement" which varies from country to country. However, there are differing views such as by Matt Cavanagh, who criticised equality of opportunity in his 2002 book Against Equality of Opportunity. Cavanagh favored a limited approach of opposing specific kinds of discrimination as steps to help people get greater control over their lives.

Conservative thinker Dinesh D'Souza criticized equality of opportunity on the basis that "it is an ideal that cannot and should not be realized through the actions of the government" and added that "for the state to enforce equal opportunity would be to contravene the true meaning of the Declaration and to subvert the principle of a free society". D'Souza described how his parenting undermined equality of opportunity:

I have a five-year-old daughter. Since she was born ... my wife and I have gone to great lengths in the Great Yuppie Parenting Race. ... My wife goes over her workbooks. I am teaching her chess. Why are we doing these things? We are, of course, trying to develop her abilities so that she can get the most out of life. The practical effect of our actions, however, is that we are working to give our daughter an edge – that is, a better chance to succeed than everybody else's children. Even though we might be embarrassed to think of it this way, we are doing our utmost to undermine equal opportunity. So are all the other parents who are trying to get their children into the best schools

D'Souza argued that it was wrong for the government to try to bring his daughter down, or to force him to raise other people's children, but a counterargument is that there is a benefit to everybody, including D'Souza's daughter, to have a society with less anxiety about downward mobility, less class resentment, and less possible violence.

An argument similar to D'Souza's was raised in Anarchy, State, and Utopia by Robert Nozick, who wrote that the only way to achieve equality of opportunity was "directly worsening the situations of those more favored with opportunity, or by improving the situation of those less well-favored". Nozick gave an argument of two suitors competing to marry one "fair lady": X was plain while Y was better looking and more intelligent. If Y did not exist, then "fair lady" would have married X, but Y exists and so she marries Y. Nozick asks: "Does suitor X have a legitimate complaint against Y based on unfairness since Y did not earn his good looks or intelligence?". Nozick suggests that there are no grounds for complaint. Nozick argued against equality of opportunity because it violates the rights of property since the equal opportunity maxim interferes with an owner's right to do what he or she pleases with a property.

Property rights were a major component of the philosophy of John Locke and are sometimes referred to as "Lockean rights". The sense of the argument is along these lines: equal opportunity rules regarding, say, a hiring decision within a factory, made to bring about greater fairness, violate a factory owner's rights to run the factory as he or she sees best; it has been argued that a factory owner's right to property encompasses all decision-making within the factory as being part of those property rights. That some people's "natural assets" were unearned is irrelevant to the equation according to Nozick and he argued that people are nevertheless entitled to enjoy these assets and other things freely given by others.

Friedrich Hayek felt that luck was too much of a variable in economics, such that one can not devise a system with any kind of fairness when many market outcomes are unintended. By sheer chance or random circumstances, a person may become wealthy just by being in the right place and time and Hayek argued that it is impossible to devise a system to make opportunities equal without knowing how such interactions may play out. Hayek saw not only equality of opportunity, but all of social justice as a "mirage".

Some conceptions of equality of opportunity, particularly the substantive and level playing field variants, have been criticized on the basis that they make assumptions to the effect that people have similar genetic makeups. Other critics have suggested that social justice is more complex than mere equality of opportunity. Nozick made the point that what happens in society can not always be reduced to competition for a coveted position and in 1974 wrote that "life is not a race in which we all compete for a prize which someone has established", that there is "no unified race" and there is not someone person "judging swiftness".