Institutions are a principal object of study in social sciences such as political science, anthropology, economics, and sociology (the latter described by Émile Durkheim as the "science of institutions, their genesis and their functioning"). Primary or meta-institutions are institutions such as the family or money that are broad enough to encompass sets of related institutions. Institutions are also a central concern for law, the formal mechanism for political rule-making and enforcement. Historians study and document the founding, growth, decay and development of institutions as part of political, economic and cultural history.

Definition

There are a variety of definitions of the term institution. These definitions entail varying levels of formality and organizational complexity. The most expansive definitions may include informal but regularized practices, such as handshakes, whereas the most narrow definitions may only include institutions that are highly formalized (e.g. have specified laws, rules and complex organizational structures).

According to Wolfgang Streeck and Kathleen Thelen, institutions are, in the most general sense, "building blocks of social order: they represent socially sanctioned, that is, collectively enforced expectations with respect to the behavior of specific categories of actors or to the performance of certain activities. Typically, they involve mutually related rights and obligations for actors." Sociologists and anthropologists have expansive definitions of institutions that include informal institutions. Political scientists have sometimes defined institutions in more formal ways where third parties must reliably and predictably enforce the rules governing the transactions of first and second parties.

One prominent Rational Choice Institutionalist definition of institutions is provided by Jack Knight who defines institutions as entailing "a set of rules that structure social interactions in particular ways" and that "knowledge of these rules must be shared by the members of the relevant community or society." Definitions by Knight and Randall Calvert exclude purely private idiosyncrasies and conventions.

Douglass North argues that institutions are "humanly devised constraints that shape interaction". According to North, they are critical determinants of economic performance, having profound effects on the costs of exchange and production. He emphasizes that small historical and cultural features can drastically change the nature of an institution. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson agree with the analysis presented by North. They write that institutions play a crucial role in the trajectory of economic growth because economic institutions shape the opportunities and constraints of investment. Economic incentives also shape political behavior, as certain groups receive more advantages from economic outcomes than others, which allow them to gain political control. A separate paper by Acemoglu, Robinson, and Francisco A. Gallego details the relationships between institutions, human capital, and economic development. They argue that institutions set an equal playing field for competition, making institutional strength a key factor in economic growth. Authors Steven Levitsky and María Victoria Murillo claim that institutional strength depends on two factors: stability and enforcement. An unstable, unenforced institution is one where weak rules are ignored and actors are unable to make expectations based on their behavior. In a weak institution, actors cannot depend on one another to act according to the rules, which creates barriers to collective action and collaboration.

Other social scientists have examined the concept of institutional lock-in. In an article entitled "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY" (1985), economist Paul A. David describes technological lock-in as the process by which a specific technology dominates the market, even when the technology is not the most efficient of the ones available. He proceeds to explain that lock-in is a result of path-dependence, where the early choice of technology in a market forces other actors to choose that technology regardless of their natural preferences, causing that technology to "lock-in". Economist W. Brian Arthur applied David's theories to institutions. As with a technology, institutions (in the form of law, policy, social regulations, or otherwise) can become locked into a society, which in turn can shape social or economic development. Arthur notes that although institutional lock-in can be predictable, it is often difficult to change once it is locked-in because of its deep roots in social and economic frameworks.

Randall Calvert defines institution as "an equilibrium of behavior in an underlying game." This means that "it must be rational for nearly every individual to almost always adhere to the behavior prescriptions of the institution, given that nearly all other individuals are doing so."

Robert Keohane defined institutions as "persistent and connected sets of rules (formal or informal) that prescribe behavioral roles, constrain activity, and shape expectations." Samuel P. Huntington defined institutions as "stable, valued, recurring patterns of behavior."

Avner Greif and David Laitin define institutions "as a system of human-made, nonphysical elements – norms, beliefs, organizations, and rules – exogenous to each individual whose behavior it influences that generates behavioral regularities." Additionally, they specify that organizations "are institutional elements that influence the set of beliefs and norms that can be self-enforcing in the transaction under consideration. Rules are behavioral instructions that facilitate individuals with the cognitive task of choosing behavior by defining the situation and coordinating behavior."

All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions and norms are all examples of institutions. Organizations and institutions can be synonymous, but Jack Knight writes that organizations are a narrow version of institutions or represent a cluster of institutions; the two are distinct in the sense that organizations contain internal institutions (that govern interactions between the members of the organizations).

An informal institution tends to have socially shared rules, which are unwritten and yet are often known by all inhabitants of a certain country, as such they are often referred to as being an inherent part of the culture of a given country. Informal practices are often referred to as "cultural", for example clientelism or corruption is sometimes stated as a part of the political culture in a certain place, but an informal institution itself is not cultural, it may be shaped by culture or behaviour of a given political landscape, but they should be looked at in the same way as formal institutions to understand their role in a given country. The relationship between formal and informal institutions is often closely aligned and informal institutions step in to prop up inefficient institutions. However, because they do not have a centre, which directs and coordinates their actions, changing informal institutions is a slow and lengthy process.

According to Geoffrey M. Hodgson, it is misleading to say that an institution is a form of behavior. Instead, Hodgson states that institutions are "integrated systems of rules that structure social interactions."

Examples

Examples of institutions include:

- Family: The family is the center of the child's life. The family teaches children cultural values and attitudes about themselves and others – see sociology of the family. Children learn continuously from their environment. Children also become aware of class at a very early age and assign different values to each class accordingly.

- Religion: Some religion is like an ethnic or cultural category, making it less likely for the individuals to break from religious affiliations and be more socialized in this setting. Parental religious participation is the most influential part of religious socialization—more so than religious peers or religious beliefs. See sociology of religion and civil religion.

- Peer groups: A peer group is a social group whose members have interests, social positions and age in common. This is where children can escape supervision and learn to form relationships on their own. The influence of the peer group typically peaks during adolescence however peer groups generally only affect short term interests unlike the family which has long term influence.

- Economic systems: Economic systems dictate "acceptable alternatives for consumption", "social values of consumption alternatives", the "establishment of dominant values", and "the nature of involvement in consumption".

- Legal systems: Children are pressured from both parents and peers to conform and obey certain laws or norms of the group/community. Parents' attitudes toward legal systems influence children's views as to what is legally acceptable. For example, children whose parents are continually in jail are more accepting of incarceration. See jurisprudence, philosophy of law, sociology of law.

- Penal systems: The penal systems acts upon prisoners and the guards. Prison is a separate environment from that of normal society; prisoners and guards form their own communities and create their own social norms. Guards serve as "social control agents" who discipline and provide security. From the view of the prisoners, the communities can be oppressive and domineering, causing feelings of defiance and contempt towards the guards. Because of the change in societies, prisoners experience loneliness, a lack of emotional relationships, a decrease in identity and "lack of security and autonomy". Both the inmates and the guards feel tense, fearful, and defensive, which creates an uneasy atmosphere within the community. See sociology of punishment.

- Language: People learn to socialize differently depending on the specific language and culture in which they live. A specific example of this is code switching. This is where immigrant children learn to behave in accordance with the languages used in their lives: separate languages at home and in peer groups (mainly in educational settings). Depending on the language and situation at any given time, people will socialize differently. See linguistics, sociolinguistics, sociology of language.

- Mass media: The mass media are the means for delivering impersonal communications directed to a vast audience. The term media comes from Latin meaning, "middle", suggesting that the media's function is to connect people. The media can teach norms and values by way of representing symbolic reward and punishment for different kinds of behavior. Mass media has enormous effects on our attitudes and behavior, notably in regards to aggression. See media studies.

- Educational institutions – schools (preschool, primary/elementary, secondary, and post-secondary/higher –see sociology of education)

- Research community – academia and universities; research institutes – see sociology of science

- Medicine – hospitals and other health care institutions – see sociology of health and illness, medical sociology

- Military or paramilitary forces – see military sociology

- Industry – businesses, including corporations – see financial institution, factory, capitalism, division of labour, social class, industrial sociology

- Civil society or NGOs – charitable organizations; advocacy groups; political parties; think tanks; virtual communities

- Gender: Through the constant interference of gender within social structures, it is observed that it constantly interacts with other social institutions (in more or less visible ways), such as race, sexuality and family.

- Video games: Video games also fall into the category of social institutions, given the fact that the complex gamer identity is seen as being at the confluence with other social institutions, such as gender and sexuality. Also, video games frequently contribute to ideological power dynamics in society by incorporating them into discourses that associate them with other phenomena, such as aggression.

In an extended context:

- Art and culture (see also: culture industry, critical theory, cultural studies, cultural sociology)

- The nation-state – Social and political scientists often speak of the state as embodying all institutions such as schools, prisons, police, and so on. However, these institutions may be considered private or autonomous, whilst organised religion and family life certainly pre-date the advent of the nation-state. The Neo-Marxist thought of Antonio Gramsci, for instance, distinguishes between institutions of political society (police, the army, the legal system., which dominate directly and coercively) and civil society (the family, education system).

Social science perspectives

While institutions tend to appear to people in society as part of the natural, unchanging landscape of their lives, the study of institutions by the social sciences tends to reveal the nature of institutions as social constructions, artifacts of a particular time, culture and society, produced by collective human choice, though not directly by individual intention. Sociology traditionally analyzed social institutions in terms of interlocking social roles and expectations. Social institutions created and were composed of groups of roles, or expected behaviors. The social function of the institution was executed by the fulfillment of roles. Basic biological requirements, for reproduction and care of the young, are served by the institutions of marriage and family, for example, by creating, elaborating and prescribing the behaviors expected for husband/father, wife/mother, child, etc.[citation needed]

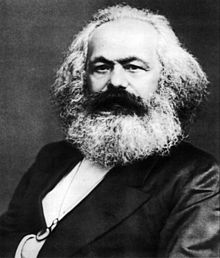

The relationship of the institutions to human nature is a foundational question for the social sciences. Institutions can be seen as "naturally" arising from, and conforming to, human nature—a fundamentally conservative view—or institutions can be seen as artificial, almost accidental, and in need of architectural redesign, informed by expert social analysis, to better serve human needs—a fundamentally progressive view. Adam Smith anchored his economics in the supposed human "propensity to truck, barter and exchange". Modern feminists have criticized traditional marriage and other institutions as element of an oppressive and obsolete patriarchy. The Marxist view—which sees human nature as historically 'evolving' towards voluntary social cooperation, shared by some anarchists—is that supra-individual institutions such as the market and the state are incompatible with the individual liberty of a truly free society.

Economics, in recent years, has used game theory to study institutions from two perspectives. Firstly, how do institutions survive and evolve? In this perspective, institutions arise from Nash equilibria of games. For example, whenever people pass each other in a corridor or thoroughfare, there is a need for customs, which avoid collisions. Such a custom might call for each party to keep to their own right (or left—such a choice is arbitrary, it is only necessary that the choice be uniform and consistent). Such customs may be supposed to be the origin of rules, such as the rule, adopted in many countries, which requires driving automobiles on the right side of the road.

Secondly, how do institutions affect behaviour? In this perspective, the focus is on behaviour arising from a given set of institutional rules. In these models, institutions determine the rules (i.e. strategy sets and utility functions) of games, rather than arise as equilibria out of games. Douglass North argues, the very emergence of an institution reflects behavioral adaptations through his application of increasing returns.[38] Over time institutions develop rules that incentivize certain behaviors over others because they present less risk or induce lower cost, and establish path dependent outcomes. For example, the Cournot duopoly model is based on an institution involving an auctioneer who sells all goods at the market-clearing price. While it is always possible to analyze behaviour with the institutions-as-equilibria approach instead, it is much more complicated.[citation needed]

In political science, the effect of institutions on behavior has also been considered from a meme perspective, like game theory borrowed from biology. A "memetic institutionalism" has been proposed, suggesting that institutions provide selection environments for political action, whereby differentiated retention arises and thereby a Darwinian evolution of institutions over time. Public choice theory, another branch of economics with a close relationship to political science, considers how government policy choices are made, and seeks to determine what the policy outputs are likely to be, given a particular political decision-making process and context. Credibility thesis purports that institutions emerge from intentional institution-building but never in the originally intended form.[39] Instead, institutional development is endogenous and spontaneously ordered and institutional persistence can be explained by their credibility,[40] which is provided by the function that particular institutions serve.

Political scientists have traditionally studied the causes and consequences of formal institutional design.[41] For instance, Douglass North investigated the impact of institutions on economic development in various countries, concluding that institutions in prosperous countries like the United States induced a net increase in productivity, whereas institutions in Third World countries caused a net decrease.[42] Scholars of this period assumed that "parchment institutions" that were codified as law would largely guide the behavior of individuals as intended.[43]

On the other hand, recent scholars began to study the importance of institutional strength, which Steven Levitsky and María Victoria Murillo define in terms of the level of enforcement and sustainability of an institution.[44] Weak institutions with low enforcement or low sustainability led to the deterioration of democratic institutions in Madagascar[45] and the erosion of economic structures in China.[46] Another area of interest for modern scholars is de facto (informal) institutions as opposed to de jure (formal) institutions in observing cross-country differences.[47] For instance, Lars Feld and Stefan Voigt found that real GDP growth per capita is positively correlated with de facto, not de juri, institutions that are judicially independent.[48] Scholars have also focused on the interaction between formal and informal institutions as well as how informal institutions may create incentives to comply with otherwise weak formal institutions.[49] This departure from the traditional understanding of institutions reflects the scholarly recognition that a different framework of institutional analysis is necessary for studying developing economies and democracies compared to developed countries.[41]

In history, a distinction between eras or periods, implies a major and fundamental change in the system of institutions governing a society. Political and military events are judged to be of historical significance to the extent that they are associated with changes in institutions. In European history, particular significance is attached to the long transition from the feudal institutions of the Middle Ages to the modern institutions, which govern contemporary life.

Theories of institutional emergence

Scholars have proposed different approaches to the emergence of institutions, such as spontaneous emergence, evolution and social contracts. In Institutions: Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Douglas North argues that institutions may be created, such as a country's constitution; or that they may evolve over time as societies evolve.[50] In the case of institutional evolution, it is harder to see them since societal changes happen in a slow manner, despite the perception that institutional change is rapid.[51] Furthermore, institutions change incrementally because of how embedded they are in society. North argues that the nature of these changes is complicated process because of the changes in rules, informal constraints, and the effectiveness of enforcement of these institutions.

Levitsky and Murillo explore the way institutions are created. When it comes to institutional design, the timeframe in which these institutions are created by different actors may affect the stability the institution will have on society, because in these cases the actors may have more (or less) time to fully calculate the impacts the institution in question will have, the way the new rules affect people's interests and their own, and the consequences of the creation of a new institution will have in society. Scholars like Christopher Kingston and Gonzalo Caballero also pose the importance of gradual societal change in the emergence of brand new institutions: these changes will determine which institutions will be successful in surviving, spreading, and becoming successful. The decisions actors within a society make also have lot to do in the survival and eventual evolution of an institution: they foster groups who want to maintain the set of rules of the game (as described by North), keeping a status quo impeding institutional change.[52] People's interests play an important role in determining the direction of institutional change and emergence.[52]

Some scholars argue that institutions can emerge spontaneously without intent as individuals and groups converge on a particular institutional arrangement.[53][54] Other approaches see institutional development as the result of evolutionary or learning processes. For instance, Pavlović explores the way compliance and socio-economic conditions in a consolidated democratic state are important in the emergence of institutions and the compliance power they have for the rules imposed. In his work, he explains the difference between wealthy societies and non-wealthy societies; wealthy societies on one hand often have institutions that have been functioning for a while, but also have a stable economy and economic development that has a direct effect in the society's democratic stability.[55] He presents us with three scenarios in which institutions may thrive in poor societies with no democratic background. First, if electoral institutions guarantee multiple elections that are widely accepted; second, if military power is in evenly equilibrium; and third, if this institutions allow for different actors to come to power.[55]

Other scholars see institutions as being formed through social contracts[56] or rational purposeful designs.[57]

Theories of institutional change

Origin of institutional theory

John Meyer and Brian Rowan were the first scholars to introduce institutional theory to inspect how organizations are shaped by their social and political environments and how they evolve in different ways. Other scholars like Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell proposed one of the forms of institutional change shortly after: institutional isomorphism. There were three main proposals. The first one is the coercive process where organizations adopt changes consistent with their larger institution due to pressures from other organizations which they might depend on or be regulated by. Such examples include state mandates or supplier demands. The second one is the mimetic process where organizations adopt other organizations' practices to resolve internal uncertainty about their own actions or strategy. Lastly, it is the normative pressure where organizations adopt changes related to the professional environment like corporate changes or cultural changes in order to be consistent.

In order to understand why some institutions persist and other institutions only appear in certain contexts, it is important to understand what drives institutional change. Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson assert that institutional change is endogenous. They posit a framework for institutional change that is rooted in the distribution of resources across society and preexisting political institutions. These two factors determine de jure and de facto political power, respectively, which in turn defines this period's economic institutions and the next period's political institutions. Finally, the current economic institutions determine next period's distribution of resources and the cycle repeats.[58] Douglass North attributes institutional change to the work of "political entrepreneurs", who see personal opportunities to be derived from a changed institutional framework. These entrepreneurs weigh the expected costs of altering the institutional framework against the benefits they can derive from the change.[59] North describes the institutional change as a process that is extremely incremental, and that works through both formal and informal institutions. North also proposes that institutional change, inefficiencies, and economic stagnations can be attributed to the differences between institutions and organizations.[60] This is because organizations are created to take advantage of the opportunities created by institutions and, as organizations evolve, these institutions are then altered. Overall, according to North, this institutional change would then be shaped by a lock-in symbiotic relationship between institutions and organizations and a feedback process by which the people in a society may perceive and react to these changes.[60] Lipscy argues that patterns of institutional change vary according to underlying characteristics of issue areas, such as network effects.[61] North also offers an efficiency hypothesis, stating that relative price changes create incentives to create more efficient institutions. It is a utilitarian argument that assumes institutions will evolve to maximize overall welfare for economic efficiency.

Contrastingly, in Variation in Institutional Strength, Levitksy and Murillo acknowledge that some formal institutions are "born weak," and attribute this to the actors creating them. They argue that the strength of institutions relies on the enforcement of laws and stability, which many actors are either uninterested in or incapable of supporting. Similarly, Brian Arthur refers to these factors as properties of non-predictability and potential inefficiency in matters where increasing returns occur naturally in economics.[62] According to Mansfield and Snyder, many transitional democracies lack state institutions that are strong and coherent enough to regulate mass political competition.[63] According to Huntington, the countries with ineffective or weak institutions often have a gap between high levels of political participation and weak political institutions, which may provoke nationalism in democratizing countries.[64] Regardless of whether the lack of enforcement and stability in institutions is intentional or not, weakly enforced institutions can create lasting ripples in a society and their way of functioning. Good enforcement of laws can be classified as a system of rules that are complied with in practice and has a high risk of punishment. It is essential because it will create a slippery slope effect on most laws and transform the nature of once-effective institutions.

Many may identify the creation of these formal institutions as a fitting way for agents to establish legitimacy in an international or domestic domain, a phenomenon identified by DiMaggio and Powell and Meyer and Rowan as "isomorphism" and that Levitsky and Murillo liken to window dressing.[65][66] They describe the developing world institutions as "window-dressing institutions" that "are often a response to international demands or expectations." It also provides an effective metaphor for something that power holders have an interest in keeping on the books, but no interest in enforcing.

The dependence developing countries have on international assistance for loans or political power creates incentives for state elites to establish a superficial form of Western government but with malfunctioning institutions.

In a 2020 study, Johannes Gerschewski created a two-by-two typology of institutional change depending on the sources of change (exogenous or endogenous) and the time horizon of change (short or long).[67] In another 2020 study, Erik Voeten created a two-by-two typology of institutional design depending on whether actors have full agency or are bound by structures, and whether institutional designs reflect historical processes or are optimal equilibriums.[68]

Institutions and economic development In the context of institutions and how they are formed, North suggests that institutions ultimately work to provide social structure in society and to incentivize individuals who abide by this structure. North explains that there is in fact a difference between institutions and organizations and that organizations are "groups of people bound by some common purpose to achieve objectives."[69] Additionally, because institutions serve as an umbrella for smaller groups such as organizations, North discusses the impact of institutional change and the ways in which it can cause economic performance to decline or become better depending on the occurrence. This is known as "path dependence" which North explains is the idea of historical and cultural events impacting the development of institutions over time. Even though North argues that institutions due to their structure do not possess the ability to change drastically, path dependence and small differences have the ability to cause change over a long period of time. For example, Levitsky and Murillo stress the importance of institutional strength in their article "Variation in Institutional Strength." They suggest that in order for an institution to maintain strength and resistance there must be legitimacy within the different political regimes, variation in political power, and political autonomy within a country. Legitimacy allows for there to be an incentive to comply with institutional rules and conditions, leading to a more effective institution. With political power, its centralization within a small group of individual leaders makes it easier and more effective to create rules and run an institution smoothly. However, it can be abused by individual leaders which is something that can contribute to the weakening of an institution over time. Lastly, independence within an institution is vital because the institutions are making decisions based on expertise and norms that they have created and built over time rather than considerations from other groups or institutions.[70] Having the ability to operate as an independent institution is crucial for its strength and resistance over time. An example of the importance of institutional strength can be found in Lacatus' essay on national human rights institutions in Europe, where she states that "As countries become members of GANHRI, their NHRIs are more likely to become stronger over time and show a general pattern of isomorphism regarding stronger safeguards for durability."[71] This demonstrates that institutions running independently and further creating spaces for the formation of smaller groups with other goals and objectives is crucial for an institution's survival.

Additionally, technological developments are important in the economic development of an institution. As detailed by Brian Arthur in "Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-in by Historical Events", technological advancements play a crucial role in shaping the economic stability of an institution. He talks about the "lock-in" phenomenon in which adds a lot of value to a piece of technology that is used by many people. It is important for policymakers and people of higher levels within an institution to consider when looking at products that have a long term impact on markets and economic developments and stability. For example, recently the EU has banned TikTok from official devices across all three government institutions. This was due to "cybersecurity concerns" and data protection in regards to data collection by "third parties."[72] This concern regarding TikTok's growing popularity demonstrates the importance of technological development within an institutional economy. Without having an understanding of what these products are doing or selling to the consumers, there runs a risk of it weakening an institution and causing more harm than good if not carefully considered and examined by the individual actors within an institution. This can also be seen in the recent issue with Silvergate and money being moved to crypto exchanges under the SEN Platform institution, which has led the bank to "delay the filing of its annual report due to questions from its auditors."[73] Additionally, they lost many crypto clients the next day allowing the bank's stock price to fall by 60% before it stabilized again. These examples demonstrate the ways in which institutions and the economy interact, and how the well being of the economy is essential for the institution's success and ability to run smoothly.

Institutional persistence

North argues that because of the preexisting influence that existing organizations have over the existing framework, change that is brought about is often in the interests of these organizations. This is because organizations are created to take advantage of such opportunities and, as organizations evolve, these institutions are altered.[60]

This produces a phenomenon called path dependence, which states that institutional patterns are persistent and endure over time.[74] These paths are determined at critical junctures, analogous to a fork in the road, whose outcome leads to a narrowing of possible future outcomes. Once a choice is made during a critical juncture, it becomes progressively difficult to return to the initial point where the choice was made. James Mahoney studies path dependence in the context of national regime change in Central America and finds that liberal policy choices of Central American leaders in the 19th century was the critical juncture that led to the divergent levels of development that we see in these countries today.[75] The policy choices that leaders made in the context of liberal reform policy led to a variety of self-reinforcing institutions that created divergent development outcomes for the Central American countries.

Though institutions are persistent, North states that paths can change course when external forces weaken the power of an existing organization. This allows other entrepreneurs to affect change in the institutional framework. This change can also occur as a result of gridlock between political actors produced by a lack of mediating institutions and an inability to reach a bargain.[76] Artificial implementation of institutional change has been tested in political development but can have unintended consequences. North, Wallis, and Weingast divide societies into different social orders: open access orders, which about a dozen developed countries fall into today, and limited access orders, which accounts for the rest of the countries. Open access orders and limited access orders differ fundamentally in the way power and influence is distributed. As a result, open access institutions placed in limited access orders face limited success and are often coopted by the powerful elite for self-enrichment. Transition to more democratic institutions is not created simply by transplanting these institutions into new contexts, but happens when it is in the interest of the dominant coalition to widen access.[77]

Natural selection

Ian Lustick suggests that the social sciences, particularly those with the institution as a central concept, can benefit by applying the concept of natural selection to the study of how institutions change over time.[78] By viewing institutions as existing within a fitness landscape, Lustick argues that the gradual improvements typical of many institutions can be seen as analogous to hill-climbing within one of these fitness landscapes. This can eventually lead to institutions becoming stuck on local maxima, such that for the institution to improve any further, it would first need to decrease its overall fitness score (e.g., adopt policies that may cause short-term harm to the institution's members). The tendency to get stuck on local maxima can explain why certain types of institutions may continue to have policies that are harmful to its members or to the institution itself, even when members and leadership are all aware of the faults of these policies.

As an example, Lustick cites Amyx's analysis of the gradual rise of the Japanese economy and its seemingly sudden reversal in the so-called "Lost Decade". According to Amyx, Japanese experts were not unaware of the possible causes of Japan's economic decline. Rather, to return Japan's economy back to the path to economic prosperity, policymakers would have had to adopt policies that would first cause short-term harm to the Japanese people and government. Under this analysis, says Ian Lustick, Japan was stuck on a "local maxima", which it arrived at through gradual increases in its fitness level, set by the economic landscape of the 1970s and 80s. Without an accompanying change in institutional flexibility, Japan was unable to adapt to changing conditions, and even though experts may have known which changes the country needed, they would have been virtually powerless to enact those changes without instituting unpopular policies that would have been harmful in the short-term.[78][79]

The lessons from Lustick's analysis applied to Sweden's economic situation can similarly apply to the political gridlock that often characterizes politics in the United States. For example, Lustick observes that any politician who hopes to run for elected office stands very little to no chance if they enact policies that show no short-term results. There is a mismatch between policies that bring about short-term benefits with minimal sacrifice, and those that bring about long-lasting change by encouraging institution-level adaptations.[citation needed]

There are some criticisms to Lustick's application of natural selection theory to institutional change. Lustick himself notes that identifying the inability of institutions to adapt as a symptom of being stuck on a local maxima within a fitness landscape does nothing to solve the problem. At the very least, however, it might add credibility to the idea that truly beneficial change might require short-term harm to institutions and their members. David Sloan Wilson notes that Lustick needs to more carefully distinguish between two concepts: multilevel selection theory and evolution on multi-peaked landscapes.[78] Bradley Thayer points out that the concept of a fitness landscape and local maxima only makes sense if one institution can be said to be "better" than another, and this in turn only makes sense insofar as there exists some objective measure of an institution's quality. This may be relatively simple in evaluating the economic prosperity of a society, for example, but it is difficult to see how objectively a measure can be applied to the amount of freedom of a society, or the quality of life of the individuals within.[78]

Institutionalization

The term "institutionalization" is widely used in social theory to refer to the process of embedding something (for example a concept, a social role, a particular value or mode of behavior) within an organization, social system, or society as a whole. The term may also be used to refer to committing a particular individual to an institution, such as a mental institution. To this extent, "institutionalization" may carry negative connotations regarding the treatment of, and damage caused to, vulnerable human beings by the oppressive or corrupt application of inflexible systems of social, medical, or legal controls by publicly owned, private or not-for-profit organizations.

The term "institutionalization" may also be used in a political sense to apply to the creation or organization of governmental institutions or particular bodies responsible for overseeing or implementing policy, for example in the welfare or development.