In genetics

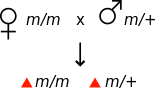

In genetics, a maternal effect occurs when the phenotype of an organism is determined by the genotype of its mother. For example, if a mutation is maternal effect recessive, then a female homozygous for the mutation may appear phenotypically normal, however her offspring will show the mutant phenotype, even if they are heterozygous for the mutation.

Maternal effects often occur because the mother supplies a particular mRNA or protein to the oocyte, hence the maternal genome determines whether the molecule is functional. Maternal supply of mRNAs to the early embryo is important, as in many organisms the embryo is initially transcriptionally inactive. Because of the inheritance pattern of maternal effect mutations, special genetic screens are required to identify them. These typically involve examining the phenotype of the organisms one generation later than in a conventional (zygotic) screen, as their mothers will be potentially homozygous for maternal effect mutations that arise.

In Drosophila early embryogenesis

A Drosophila melanogaster oocyte develops in an egg chamber in close association with a set of cells called nurse cells. Both the oocyte and the nurse cells are descended from a single germline stem cell, however cytokinesis is incomplete in these cell divisions, and the cytoplasm of the nurse cells and the oocyte is connected by structures known as ring canals. Only the oocyte undergoes meiosis and contributes DNA to the next generation.

Many maternal effect Drosophila mutants have been found that affect the early steps in embryogenesis such as axis determination, including bicoid, dorsal, gurken and oskar. For example, embryos from homozygous bicoid mothers fail to produce head and thorax structures.

Once the gene that is disrupted in the bicoid mutant was identified, it was shown that bicoid mRNA is transcribed in the nurse cells and then relocalized to the oocyte. Other maternal effect mutants either affect products that are similarly produced in the nurse cells and act in the oocyte, or parts of the transportation machinery that are required for this relocalization. Since these genes are expressed in the (maternal) nurse cells and not in the oocyte or fertilised embryo, the maternal genotype determines whether they can function.

Maternal effect genes are expressed during oogenesis by the mother (expressed prior to fertilization) and develop the anterior-posterior and dorsal ventral polarity of the egg. The anterior end of the egg becomes the head; posterior end becomes the tail. the dorsal side is on the top; the ventral side is in underneath. The products of maternal effect genes called maternal mRNAs are produced by nurse cell and follicle cells and deposited in the egg cells (oocytes). At the start of development process, mRNA gradients are formed in oocytes along anterior-posterior and dorsal ventral axes.

About thirty maternal genes are involved in pattern formation have been identified. In particular, products of four maternal effect genes are critical to the formation of anterior-posterior axis. The product of two maternal effect gene, bicoid and hunchback, regulates formation of anterior structure while another pair nanos and caudal, specifies protein that regulates formation of posterior part of embryo.

The transcript of all four genes-bicoid, hunchback, caudal, nanos are synthesized by nurse and follicle cells and transported into the oocytes.

In birds

In birds, mothers may pass down hormones in their eggs that affect an offspring's growth and behavior. Experiments in domestic canaries have shown that eggs that contain more yolk androgens develop into chicks that display more social dominance. Similar variation in yolk androgen levels has been seen in bird species like the American coot, though the mechanism of effect has yet to be established.

In humans

In 2015, obesity theorist Edward Archer published "The Childhood Obesity Epidemic as a Result of Nongenetic Evolution: The Maternal Resources Hypothesis" and a series of works on maternal effects in human obesity and health. In this body of work, Archer argued that accumulative maternal effects via the non-genetic evolution of matrilineal nutrient metabolism is responsible for the increased global prevalence of obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2. Archer posited that decrements in maternal metabolic control altered fetal pancreatic beta cell, adipocyte (fat cell) and myocyte (muscle cell) development thereby inducing an enduring competitive advantage of adipocytes in the acquisition and sequestering on nutrient energy.

In plants

The environmental cues such as light, temperature, soil moisture and nutrients that the mother plant encounters can cause variations in seed quality, even within the same genotype. Thus, the mother plant greatly influences seed traits such as seed size, germination rate, and viability.

Environmental maternal effects

The environment or condition of the mother can also in some situations influence the phenotype of her offspring, independent of the offspring's genotype.

Paternal effect genes

In contrast, a paternal effect is when a phenotype results from the genotype of the father, rather than the genotype of the individual. The genes responsible for these effects are components of sperm that are involved in fertilization and early development. An example of a paternal-effect gene is the ms(3)sneaky in Drosophila. Males with a mutant allele of this gene produce sperm that are able to fertilize an egg, but the sneaky-inseminated eggs do not develop normally. However, females with this mutation produce eggs that undergo normal development when fertilized.

Adaptive maternal effects

Adaptive maternal effects induce phenotypic changes in offspring that result in an increase in fitness. These changes arise from mothers sensing environmental cues that work to reduce offspring fitness, and then responding to them in a way that then “prepares” offspring for their future environments. A key characteristic of “adaptive maternal effects” phenotypes is their plasticity. Phenotypic plasticity gives organisms the ability to respond to different environments by altering their phenotype. With these “altered” phenotypes increasing fitness it becomes important to look at the likelihood that adaptive maternal effects will evolve and become a significant phenotypic adaptation to an environment.

Defining adaptive maternal effects

When traits are influenced by either the maternal environment or the maternal phenotype, it is said to be influenced by maternal effects. Maternal effects work to alter the phenotypes of the offspring through pathways other than DNA. Adaptive maternal effects are when these maternal influences lead to a phenotypic change that increases the fitness of the offspring. In general, adaptive maternal effects are a mechanism to cope with factors that work to reduce offspring fitness; they are also environment specific.

It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between maternal and adaptive maternal effects. Consider the following: Gypsy moths reared on foliage of black oak, rather than chestnut oak, had offspring that developed faster. This is a maternal, not an adaptive maternal effect. In order to be an adaptive maternal effect, the mother's environment would have to have led to a change in the eating habits or behavior of the offspring. The key difference between the two therefore, is that adaptive maternal effects are environment specific. The phenotypes that arise are in response to the mother sensing an environment that would reduce the fitness of her offspring. By accounting for this environment she is then able to alter the phenotypes to actually increase the offspring's fitness. Maternal effects are not in response to an environmental cue, and further they have the potential to increase offspring fitness, but they may not.

When looking at the likelihood of these “altered” phenotypes evolving there are many factors and cues involved. Adaptive maternal effects evolve only when offspring can face many potential environments; when a mother can “predict” the environment into which her offspring will be born; and when a mother can influence her offspring's phenotype, thereby increasing their fitness. The summation of all of these factors can then lead to these “altered” traits becoming favorable for evolution.

The phenotypic changes that arise from adaptive maternal effects are a result of the mother sensing that a certain aspect of the environment may decrease the survival of her offspring. When sensing a cue the mother “relays” information to the developing offspring and therefore induces adaptive maternal effects. This tends to then cause the offspring to have a higher fitness because they are “prepared” for the environment they are likely to experience. These cues can include responses to predators, habitat, high population density, and food availability.

The increase in size of Northern American red squirrels is a great example of an adaptive maternal effect producing a phenotype that resulted in an increased fitness. The adaptive maternal effect was induced by the mothers sensing the high population density and correlating it to low food availability per individual. Her offspring were on average larger than other squirrels of the same species; they also grew faster. Ultimately, the squirrels born during this period of high population density showed an increased survival rate (and therefore fitness) during their first winter.

Phenotypic plasticity

When analyzing the types of changes that can occur to a phenotype, we can see changes that are behavioral, morphological, or physiological. A characteristic of the phenotype that arises through adaptive maternal effects, is the plasticity of this phenotype. Phenotypic plasticity allows organisms to adjust their phenotype to various environments, thereby enhancing their fitness to changing environmental conditions. Ultimately it is a key attribute to an organism's, and a population's, ability to adapt to short term environmental change.

Phenotypic plasticity can be seen in many organisms, one species that exemplifies this concept is the seed beetle Stator limbatus. This seed beetle reproduces on different host plants, two of the more common ones being Cercidium floridum and Acacia greggii. When C. floridum is the host plant, there is selection for a large egg size; when A. greggii is the host plant, there is a selection for a smaller egg size. In an experiment it was seen that when a beetle who usually laid eggs on A. greggii was put onto C. floridum, the survivorship of the laid eggs was lower compared to those eggs produced by a beetle that was conditioned and remained on the C. florium host plant. Ultimately these experiments showed the plasticity of egg size production in the beetle, as well as the influence of the maternal environment on the survivorship of the offspring.

Further examples of adaptive maternal effects

In many insects:

- Cues such as rapidly cooling temperatures or decreasing daylight can result in offspring that enter into a dormant state. They therefore will better survive the cooling temperatures and preserve energy.

- When parents are forced to lay eggs on environments with low nutrients, offspring will be provided with more resources, such as higher nutrients, through an increased egg size.

- Cues such as poor habitat or crowding can lead to offspring with wings. The wings allow the offspring to move away from poor environments to ones that will provide better resources.

Maternal diet and environment influence epigenetic effects

Related to adaptive maternal effects are epigenetic effects. Epigenetics is the study of long lasting changes in gene expression that are produced by modifications to chromatin instead of changes in DNA sequence, as is seen in DNA mutation. This "change" refers to DNA methylation, histone acetylation, or the interaction of non-coding RNAs with DNA. DNA methylation is the addition of methyl groups to the DNA. When DNA is methylated in mammals, the transcription of the gene at that location is turned down or turned off entirely. The induction of DNA methylation is highly influenced by the maternal environment. Some maternal environments can lead to a higher methylation of an offspring's DNA, while others lower methylation. The fact that methylation can be influenced by the maternal environment, makes it similar to adaptive maternal effects. Further similarities are seen by the fact that methylation can often increase the fitness of the offspring. Additionally, epigenetics can refer to histone modifications or non-coding RNAs that create a sort of cellular memory. Cellular memory refers to a cell's ability to pass nongenetic information to its daughter cell during replication. For example, after differentiation, a liver cell performs different functions than a brain cell; cellular memory allows these cells to "remember" what functions they are supposed to perform after replication. Some of these epigenetic changes can be passed down to future generations, while others are reversible within a particular individual's lifetime. This can explain why individuals with identical DNA can differ in their susceptibility to certain chronic diseases.

Currently, researchers are examining the correlations between maternal diet during pregnancy and its effect on the offspring's susceptibility for chronic diseases later in life. The fetal programming hypothesis highlights the idea that environmental stimuli during critical periods of fetal development can have lifelong effects on body structure and health and in a sense they prepare offspring for the environment they will be born into. Many of these variations are thought to be due to epigenetic mechanisms brought on by maternal environment such as stress, diet, gestational diabetes, and exposure to tobacco and alcohol. These factors are thought to be contributing factors to obesity and cardiovascular disease, neural tube defects, cancer, diabetes, etc. Studies to determine these epigenetic mechanisms are usually performed through laboratory studies of rodents and epidemiological studies of humans.

Importance for the general population

Knowledge of maternal diet induced epigenetic changes is important not only for scientists, but for the general public. Perhaps the most obvious place of importance for maternal dietary effects is within the medical field. In the United States and worldwide, many non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, obesity, and heart disease, have reached epidemic proportions. The medical field is working on methods to detect these diseases, some of which have been discovered to be heavily driven by epigenetic alterations due to maternal dietary effects. Once the genomic markers for these diseases are identified, research can begin to be implemented to identify the early onset of these diseases and possibly reverse the epigenetic effects of maternal diet in later life stages. The reversal of epigenetic effects will utilize the pharmaceutical field in an attempt to create drugs which target the specific genes and genomic alterations. The creation of drugs to cure these non-communicable diseases could be used to treat individuals who already have these illnesses. General knowledge of the mechanisms behind maternal dietary epigenetic effects is also beneficial in terms of awareness. The general public can be aware of the risks of certain dietary behaviors during pregnancy in an attempt to curb the negative consequences which may arise in offspring later in their lives. Epigenetic knowledge can lead to an overall healthier lifestyle for the billions of people worldwide.

The effect of maternal diet in species other than humans is also relevant. Many of the long term effects of global climate change are unknown. Knowledge of epigenetic mechanisms can help scientists better predict the impacts of changing community structures on species which are ecologically, economically, and/or culturally important around the world. Since many ecosystems will see changes in species structures, the nutrient availability will also be altered, ultimately affecting the available food choices for reproducing females. Maternal dietary effects may also be used to improve agricultural and aquaculture practices. Breeders may be able to utilize scientific data to create more sustainable practices, saving money for themselves, as well as the consumers.

Maternal diet and environment epigenetically influences susceptibility for adult diseases

Hyperglycemia during pregnancy is thought to cause epigenetic changes in the leptin gene of newborns leading to a potential increased risk for obesity and heart disease. Leptin is sometimes known as the “satiety hormone” because it is released by fat cells to inhibit hunger. By studying both animal models and human observational studies, it has been suggested that a leptin surge in the perinatal period plays a critical role in contributing to long-term risk of obesity. The perinatal period begins at 22 weeks gestation and ends a week after birth. DNA methylation near the leptin locus has been examined to determine if there was a correlation between maternal glycemia and neonatal leptin levels. Results showed that glycemia was inversely associated with the methylation states of LEP gene, which controls the production of the leptin hormone. Therefore, higher glycemic levels in mothers corresponded to lower methylation states in LEP gene in their children. With this lower methylation state, the LEP gene is transcribed more often, thereby inducing higher blood leptin levels. These higher blood leptin levels during the perinatal period were linked to obesity in adulthood, perhaps due to the fact that a higher “normal” level of leptin was set during gestation. Because obesity is a large contributor to heart disease, this leptin surge is not only correlated with obesity but also heart disease.

High fat diets in utero are believed to cause metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a set of symptoms including obesity and insulin resistance that appear to be related. This syndrome is often associated with type II diabetes as well as hypertension and atherosclerosis. Using mice models, researchers have shown that high fat diets in utero cause modifications to the adiponectin and leptin genes that alter gene expression; these changes contribute to metabolic syndrome. The adiponectin genes regulate glucose metabolism as well as fatty acid breakdown; however, the exact mechanisms are not entirely understood. In both human and mice models, adiponectin has been shown to add insulin-sensitizing and anti-inflammatory properties to different types of tissue, specifically muscle and liver tissue. Adiponectin has also been shown to increase the rate of fatty acid transport and oxidation in mice, which causes an increase in fatty acid metabolism. With a high fat diet during gestation, there was an increase in methylation in the promoter of the adiponectin gene accompanied by a decrease in acetylation. These changes likely inhibit the transcription of the adiponectin genes because increases in methylation and decreases in acetylation usually repress transcription. Additionally, there was an increase in methylation of the leptin promoter, which turns down the production of the leptin gene. Therefore, there was less adiponectin to help cells take up glucose and break down fat, as well as less leptin to cause a feeling of satiety. The decrease in these hormones caused fat mass gain, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, abnormal adiponectin and leptin levels, and hypertension throughout the animal's lifetime. However, the effect was abolished after three subsequent generations with normal diets. This study highlights the fact that these epigenetic marks can be altered in as many as one generation and can even be completely eliminated over time. This study highlighted the connection between high fat diets to the adiponectin and leptin in mice. In contrast, few studies have been done in humans to show the specific effects of high fat diets in utero on humans. However, it has been shown that decreased adiponectin levels are associated with obesity, insulin resistance, type II diabetes, and coronary artery disease in humans. It is postulated that a similar mechanism as the one described in mice may also contribute to metabolic syndrome in humans.

In addition, high fat diets cause chronic low-grade inflammation in the placenta, adipose, liver, brain, and vascular system. Inflammation is an important aspect of the bodies’ natural defense system after injury, trauma, or disease. During an inflammatory response, a series of physiological reactions, such as increased blood flow, increased cellular metabolism, and vasodilation, occur in order to help treat the wounded or infected area. However, chronic low-grade inflammation has been linked to long-term consequences such as cardiovascular disease, renal failure, aging, diabetes, etc. This chronic low-grade inflammation is commonly seen in obese individuals on high fat diets. In a mice model, excessive cytokines were detected in mice fed on a high fat diet. Cytokines aid in cell signaling during immune responses, specifically sending cells towards sites of inflammation, infection, or trauma. The mRNA of proinflammatory cytokines was induced in the placenta of mothers on high fat diets. The high fat diets also caused changes in microbiotic composition, which led to hyperinflammatory colonic responses in offspring. This hyperinflammatory response can lead to inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. As previously mentioned, high fat diets in utero contribute to obesity; however, some proinflammatory factors, like IL-6 and MCP-1, are also linked to body fat deposition. It has been suggested that histone acetylation is closely associated with inflammation because the addition of histone deacetylase inhibitors has been shown to reduce the expression of proinflammatory mediators in glial cells. This reduction in inflammation resulted in improved neural cell function and survival. This inflammation is also often associated with obesity, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver, brain damage, as well as preeclampsia and preterm birth. Although it has been shown that high fat diets induce inflammation, which contribute to all these chronic diseases; it is unclear as to how this inflammation acts as a mediator between diet and chronic disease.

A study done after the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-1945 showed that undernutrition during the early stages of pregnancy are associated with hypomethylation of the insulin-like growth factor II (IGF2) gene even after six decades. These individuals had significantly lower methylation rates as compared to their same sex sibling who had not been conceived during the famine. A comparison was done with children conceived prior to the famine so that their mothers were nutrient deprived during the later stages of gestation; these children had normal methylation patterns. The IGF2 stands for insulin-like growth factor II; this gene is a key contributor in human growth and development. IGF2 gene is also maternally imprinted meaning that the mother's gene is silenced. The mother's gene is typically methylated at the differentially methylated region (DMR); however, when hypomethylated, the gene is bi-allelically expressed. Thus, individuals with lower methylation states likely lost some of the imprinting effect. Similar results have been demonstrated in the Nr3c1 and Ppara genes of the offspring of rats fed on an isocaloric protein-deficient diet before starting pregnancy. This further implies that the undernutrition was the cause of the epigenetic changes. Surprisingly, there was not a correlation between methylation states and birth weight. This displayed that birth weight may not be an adequate way to determine nutritional status during gestation. This study stressed that epigenetic effects vary depending on the timing of exposure and that early stages of mammalian development are crucial periods for establishing epigenetic marks. Those exposed earlier in gestation had decreased methylation while those who were exposed at the end of gestation had relatively normal methylation levels. The offspring and descendants of mothers with hypomethylation were more likely to develop cardiovascular disease. Epigenetic alterations that occur during embryogenesis and early fetal development have greater physiologic and metabolic effects because they are transmitted over more mitotic divisions. In other words, the epigenetic changes that occur earlier are more likely to persist in more cells.

In another study, researchers discovered that perinatal nutrient restriction resulting in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) contributes to diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2). IUGR refers to the poor growth of the baby in utero. In the pancreas, IUGR caused a reduction in the expression of the promoter of the gene encoding a critical transcription factor for beta cell function and development. Pancreatic beta cells are responsible for making insulin; decreased beta cell activity is associated with DM2 in adulthood. In skeletal muscle, IUGR caused a decrease in expression of the Glut-4 gene. The Glut-4 gene controls the production of the Glut-4 transporter; this transporter is specifically sensitive to insulin. Thus, when insulin levels rise, more glut-4 transporters are brought to the cell membrane to increase the uptake of glucose into the cell. This change is caused by histone modifications in the cells of skeletal muscle that decrease the effectiveness of the glucose transport system into the muscle. Because the main glucose transporters are not operating at optimal capacity, these individuals are more likely to develop insulin resistance with energy rich diets later in life, contributing to DM2.

Further studies have examined the epigenetic changes resulting from a high protein/low carbohydrate diet during pregnancy. This diet caused epigenetic changes that were associated with higher blood pressure, higher cortisol levels, and a heightened Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response to stress. Increased methylation in the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD2), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and H19 ICR were positively correlated with adiposity and blood pressure in adulthood. Glucocorticoids play a vital role in tissue development and maturation as well as having effects on metabolism. Glucocorticoids’ access to GR is regulated by HSD1 and HSD2. H19 is an imprinted gene for a long coding RNA (lncRNA), which has limiting effects on body weight and cell proliferation. Therefore, higher methylation rates in H19 ICR repress transcription and prevent the lncRNA from regulating body weight. Mothers who reported higher meat/fish and vegetable intake and lower bread/potato intake in late pregnancy had a higher average methylation in GR and HSD2. However, one common challenge of these types of studies is that many epigenetic modifications have tissue and cell-type specificity DNA methylation patterns. Thus, epigenetic modification patterns of accessible tissues, like peripheral blood, may not represent the epigenetic patterns of the tissue involved in a particular disease.

Strong evidence in rats supports the conclusion that neonatal estrogen exposure plays a role in the development of prostate cancer. Using a human fetal prostate xenograft model, researchers studied the effects of early exposure to estrogen with and without secondary estrogen and testosterone treatment. A xenograft model is a graft of tissue transplanted between organisms of different species. In this case, human tissue was transplanted into rats; therefore, there was no need to extrapolate from rodents to humans. Histopathological lesions, proliferation, and serum hormone levels were measured at various time-points after xenografting. At day 200, the xenograft that had been exposed to two treatments of estrogen showed the most severe changes. Additionally, researchers looked at key genes involved in prostatic glandular and stromal growth, cell-cycle progression, apoptosis, hormone receptors, and tumor suppressors using a custom PCR array. Analysis of DNA methylation showed methylation differences in CpG sites of the stromal compartment after estrogen treatment. These variations in methylation are likely a contributing cause to the changes in the cellular events in the KEGG prostate cancer pathway that inhibit apoptosis and increase cell cycle progression that contribute to the development of cancer.

Supplementation may reverse epigenetic changes

In utero or neonatal exposure to bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical used in manufacturing polycarbonate plastic, is correlated with higher body weight, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and an altered reproductive function. In a mice model, the mice fed on a BPA diet were more likely to have a yellow coat corresponding to their lower methylation state in the promoter regions of the retrotransposon upstream of the Agouti gene. The Agouti gene is responsible for determining whether an animal's coat will be banded (agouti) or solid (non-agouti). However, supplementation with methyl donors like folic acid or phytoestrogen abolished the hypomethylating effect. This demonstrates that the epigenetic changes can be reversed through diet and supplementation.

Maternal diet effects and ecology

Maternal dietary effects are not just seen in humans, but throughout many taxa in the animal kingdom. These maternal dietary effects can result in ecological changes on a larger scale throughout populations and from generation to generation. The plasticity involved in these epigenetic changes due to maternal diet represents the environment into which the offspring will be born. Many times, epigenetic effects on offspring from the maternal diet during development will genetically prepare the offspring to be better adapted for the environment in which they will first encounter. The epigenetic effects of maternal diet can be seen in many species, utilizing different ecological cues and epigenetic mechanisms to provide an adaptive advantage to future generations.

Within the field of ecology, there are many examples of maternal dietary effects. Unfortunately, the epigenetic mechanisms underlying these phenotypic changes are rarely investigated. In the future, it would be beneficial for ecological scientists as well as epigenetic and genomic scientists to work together to fill the holes within the ecology field to produce a complete picture of environmental cues and epigenetic alterations producing phenotypic diversity.

Parental diet affects offspring immunity

A pyralid moth species, Plodia interpunctella, commonly found in food storage areas, exhibits maternal dietary effects, as well as paternal dietary effects, on its offspring. Epigenetic changes in moth offspring affect the production of phenoloxidase, an enzyme involved with melanization and correlated with resistance of certain pathogens in many invertebrate species. In this study, parent moths were housed in food rich or food poor environments during their reproductive period. Moths who were housed in food poor environments produced offspring with less phenoloxidase, and thus had a weaker immune system, than moths who reproduced in food rich environments. This is believed to be adaptive because the offspring develop while receiving cues of scarce nutritional opportunities. These cues allow the moth to allocate energy differentially, decreasing energy allocated for the immune system and devoting more energy towards growth and reproduction to increase fitness and insure future generations. One explanation for this effect may be imprinting, the expression of only one parental gene over the other, but further research has yet to be done.

Parental-mediated dietary epigenetic effects on immunity has a broader significance on wild organisms. Changes in immunity throughout an entire population may make the population more susceptible to an environmental disturbance, such as the introduction of a pathogen. Therefore, these transgenerational epigenetic effects can influence the population dynamics by decreasing the stability of populations who inhabit environments different from the parental environment that offspring are epigenetically modified for.

Maternal diet affects offspring growth rate

Food availability also influences the epigenetic mechanisms driving growth rate in the mouthbrooding cichlid, Simochromis pleurospilus. When nutrient availability is high, reproducing females will produce many small eggs, versus fewer, larger eggs in nutrient poor environments. Egg size often correlates with fish larvae body size at hatching: smaller larvae hatch from smaller eggs. In the case of the cichlid, small larvae grow at a faster rate than their larger egg counterparts. This is due to the increased expression of GHR, the growth hormone receptor. Increased transcription levels of GHR genes increase the receptors available to bind with growth hormone, GH, leading to an increased growth rate in smaller fish. Fish of larger size are less likely to be eaten by predators, therefore it is advantageous to grow quickly in early life stages to insure survival. The mechanism by which GHR transcription is regulated is unknown, but it may be due to hormones within the yolk produced by the mother, or just by the yolk quantity itself. This may lead to DNA methylation or histone modifications which control genic transcription levels.

Ecologically, this is an example of the mother utilizing her environment and determining the best method to maximize offspring survival, without actually making a conscious effort to do so. Ecology is generally driven by the ability of an organism to compete to obtain nutrients and successfully reproduce. If a mother is able to gather a plentiful amount of resources, she will have a higher fecundity and produce offspring who are able to grow quickly to avoid predation. Mothers who are unable to obtain as many nutrients will produce fewer offspring, but the offspring will be larger in hopes that their large size will help insure survival into sexual maturation. Unlike the moth example, the maternal effects provided to the cichlid offspring do not prepare the cichlids for the environment that they will be born into; this is because mouth brooding cichlids provide parental care to their offspring, providing a stable environment for the offspring to develop. Offspring who have a greater growth rate can become independent more quickly than slow growing counterparts, therefore decreasing the amount of energy spent by the parents during the parental care period.

A similar phenomenon occurs in the sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis. Urchin mothers in nutrient rich environments produce a large number of small eggs. Offspring from these small eggs grow at a faster rate than their large egg counterparts from nutrient poor mothers. Again, it is beneficial for sea urchin larvae, known as planula, to grow quickly to decrease the duration of their larval phase and metamorphose into a juvenile to decrease predation risks. Sea urchin larvae have the ability to develop into one of two phenotypes, based on their maternal and larval nutrition. Larvae who grow at a fast rate from high nutrition, are able to devote more of their energy towards development into the juvenile phenotype. Larvae who grow at a slower rate with low nutrition, devote more energy towards growing spine-like appendages to protect themselves from predators in an attempt to increase survival into the juvenile phase. The determination of these phenotypes is based on both the maternal and the juvenile nutrition. The epigenetic mechanisms behind these phenotypic changes is unknown, but it is believed that there may be a nutritional threshold that triggers epigenetic changes affecting development and, ultimately, the larval phenotype.