| History of Israel |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Land of Israel (Hebrew: אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל, Modern: ʾEreṣ Yīsraʾel, Tiberian: ʾEreṣ Yīsrāʾēl) is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definitions of the limits of this territory vary between passages in the Hebrew Bible, with specific mentions in Genesis 15, Exodus 23, Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47. Nine times elsewhere in the Bible, the settled land is referred as "from Dan to Beersheba", and three times it is referred as "from the entrance of Hamath unto the brook of Egypt" (1 Kings 8:65, 1 Chronicles 13:5 and 2 Chronicles 7:8).

These biblical limits for the land differ from the borders of established historical Israelite and later Jewish kingdoms, including the United Kingdom of Israel, the two kingdoms of Israel (Samaria) and Judah, the Hasmonean Kingdom, and the Herodian kingdom. At their heights, these realms ruled lands with similar but not identical boundaries.

Jewish religious belief defines the land as where Jewish religious law prevailed and excludes territory where it was not applied. It holds that the area is a God-given inheritance of the Jewish people based on the Torah, particularly the books of Genesis, Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy, as well as Joshua and the later Prophets. According to the Book of Genesis, the land was first promised by God to Abram's descendants; the text is explicit that this is a covenant between God and Abram for his descendants. Abram's name was later changed to Abraham, with the promise refined to pass through his son Isaac and to the Israelites, descendants of Jacob, Abraham's grandson. This belief is not shared by most adherents of replacement theology (or supersessionism), who hold the view that the Old Testament prophecies were superseded by the coming of Jesus, a view often repudiated by Christian Zionists as a theological error. Evangelical Zionists variously claim that Israel has title to the land by divine right,[6] or by a theological, historical and moral grounding of attachment to the land unique to Jews (James Parkes). The idea that ancient religious texts can be warrant or divine right for a modern claim has often been challenged, and Israeli courts have rejected land claims based on religious motivations.

During the League of Nations mandate period (1920–1948) the term "Eretz Yisrael" or the "Land of Israel" was part of the official Hebrew name of Mandatory Palestine. Official Hebrew documents used the Hebrew transliteration of the word "Palestine" פלשתינה (Palestina) followed always by the two initial letters of "Eretz Yisrael", א״י Aleph-Yod.

The Land of Israel concept has been evoked by the founders of the State of Israel. It often surfaces in political debates on the status of the West Bank, referred to in official Israeli discourse as the Judea and Samaria Area.

Etymology and biblical roots

The term "Land of Israel" is a direct translation of the Hebrew phrase ארץ ישראל (Eretz Yisrael), which occasionally occurs in the Bible, and is first mentioned in the Tanakh in 1 Samuel 13:19, following the Exodus, when the Israelite tribes were already in the Land of Canaan. The words are used sparsely in the Bible: King David is ordered to gather 'strangers to the land of Israel' (hag-gêrîm 'ăšer, bə'ereṣ yiśrā'êl) for building purposes (1 Chronicles 22:2), and the same phrasing is used in reference to King Solomon's census of all of the 'strangers in the Land of Israel' (2 Chronicles 2:17). Ezekiel, though generally preferring the phrase 'soil of Israel' ('admat yiśrā'êl), employs eretz Israel twice, respectively at Ezekiel 40:2 and Ezekiel 47:18.

According to Martin Noth, the term is not an "authentic and original name for this land", but instead serves as "a somewhat flexible description of the area which the Israelite tribes had their settlements". According to Anita Shapira, the term "Eretz Yisrael" was a holy term, vague as far as the exact boundaries of the territories are concerned but clearly defining ownership. The sanctity of the land (kedushat ha-aretz) developed rich associations in rabbinical thought, where it assumes a highly symbolic and mythological status infused with promise, though always connected to a geographical location. Nur Masalha argues that the biblical boundaries are "entirely fictitious", and bore simply religious connotations in Diaspora Judaism, with the term only coming into ascendency with the rise of Zionism.

The Hebrew Bible provides three specific sets of borders for the "Promised Land", each with a different purpose. Neither of the terms "Promised Land" (Ha'Aretz HaMuvtahat) or "Land of Israel" are used in these passages: Genesis 15:13–21, Genesis 17:8 and Ezekiel 47:13–20 use the term "the land" (ha'aretz), as does Deuteronomy 1:8 in which it is promised explicitly to "Abraham, Isaac and Jacob... and to their descendants after them," whilst Numbers 34:1–15 describes the "Land of Canaan" (Eretz Kna'an) which is allocated to nine and half of the twelve Israelite tribes after the Exodus. The expression "Land of Israel" is first used in a later book, 1 Samuel 13:19. It is defined in detail in the exilic Book of Ezekiel as a land where both the twelve tribes and the "strangers in (their) midst", can claim inheritance. The name "Israel" first appears in the Hebrew Bible as the name given by God to the patriarch Jacob (Genesis 32:28). Deriving from the name "Israel", other designations that came to be associated with the Jewish people have included the "Children of Israel" or "Israelite".

The term 'Land of Israel' (γῆ Ἰσραήλ) occurs in one episode in the New Testament (Matthew 2:20–21), where, according to Shlomo Sand, it bears the unusual sense of 'the area surrounding Jerusalem'. The section in which it appears was written as a parallel to the earlier Book of Exodus.

Biblical borders

Genesis 15

Genesis 15:18–21 describes what are known as "Borders of the Land" (Gevulot Ha-aretz), which in Jewish tradition defines the extent of the land promised to the descendants of Abraham, through his son Isaac and grandson Jacob. The passage describes the area as the land of the ten named ancient peoples then living there.

More precise geographical borders are given in Exodus 23:31, which describes borders as marked by the Red Sea (see debate below), the "Sea of the Philistines" i.e., the Mediterranean, and the "River", the Euphrates), the traditional furthest extent of the Kingdom of David.

Genesis gives the border with Egypt as Nahar Mitzrayim – nahar in Hebrew denotes a river or stream, as opposed to a wadi.

Exodus 23

A slightly more detailed definition is given in Exodus 23:31, which describes the borders as "from the sea of reeds (Red Sea) to the Sea of the Philistines (Mediterranean sea) and from the desert to the Euphrates River", though the Hebrew text of the Bible uses the name, "the River", to refer to the Euphrates.

Only the "Red Sea" (Exodus 23:31) and the Euphrates are mentioned to define the southern and eastern borders of the full land promised to the Israelites. The "Red Sea" corresponding to Hebrew Yam Suf was understood in ancient times to be the Erythraean Sea, as reflected in the Septuagint translation. Although the English name "Red Sea" is derived from this name ("Erythraean" derives from the Greek for red), the term denoted all the waters surrounding Arabia—including the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf, not merely the sea lying to the west of Arabia bearing this name in modern English. Thus, the entire Arabian peninsula lies within the borders described. Modern maps depicting the region take a reticent view and often leave the southern and eastern borders vaguely defined. The borders of the land to be conquered given in Numbers have a precisely defined eastern border which included the Arabah and Jordan.

Numbers 34

Numbers 34:1–15 describes the land allocated to the Israelite tribes after the Exodus. The tribes of Reuben, Gad and half of Manasseh received land east of the Jordan as explained in Numbers 34:14–15. Numbers 34:1–13 provides a detailed description of the borders of the land to be conquered west of the Jordan for the remaining tribes. The region is called "the Land of Canaan" (Eretz Kna'an) in Numbers 34:2 and the borders are known in Jewish tradition as the "borders for those coming out of Egypt". These borders are again mentioned in Deuteronomy 1:6–8, 11:24 and Joshua 1:4.

According to the Hebrew Bible, Canaan was the son of Ham who with his descendants had seized the land from the descendants of Shem according to the Book of Jubilees. Jewish tradition thus refers to the region as Canaan during the period between the Flood and the Israelite settlement. Eliezer Schweid sees Canaan as a geographical name, and Israel the spiritual name of the land. He writes: The uniqueness of the Land of Israel is thus "geo-theological" and not merely climatic. This is the land which faces the entrance of the spiritual world, that sphere of existence that lies beyond the physical world known to us through our senses. This is the key to the land's unique status with regard to prophecy and prayer, and also with regard to the commandments. Thus, the renaming of this landmarks a change in religious status, the origin of the Holy Land concept. Numbers 34:1–13 uses the term Canaan strictly for the land west of the Jordan, but Land of Israel is used in Jewish tradition to denote the entire land of the Israelites. The English expression "Promised Land" can denote either the land promised to Abraham in Genesis or the land of Canaan, although the latter meaning is more common.

The border with Egypt is given as the Nachal Mitzrayim (Brook of Egypt) in Numbers, as well as in Deuteronomy and Ezekiel. Jewish tradition (as expressed in the commentaries of Rashi and Yehuda Halevi, as well as the Aramaic Targums) understand this as referring to the Nile; more precisely the Pelusian branch of the Nile Delta according to Halevi—a view supported by Egyptian and Assyrian texts. Saadia Gaon identified it as the "Wadi of El-Arish", referring to the biblical Sukkot near Faiyum. Kaftor Vaferech placed it in the same region, which approximates the location of the former Pelusian branch of the Nile. 19th century Bible commentaries understood the identification as a reference to the Wadi of the coastal locality called El-Arish. Easton's, however, notes a local tradition that the course of the river had changed and there was once a branch of the Nile where today there is a wadi. Biblical minimalists have suggested that the Besor is intended.

Deuteronomy 19

Deuteronomy 19:8 indicates a certain fluidity of the borders of the promised land when it refers to the possibility that God would "enlarge your borders." This expansion of territory means that Israel would receive "all the land he promised to give to your fathers", which implies that the settlement actually fell short of what was promised. According to Jacob Milgrom, Deuteronomy refers to a more utopian map of the promised land, whose eastern border is the wilderness rather than the Jordan.

Paul R. Williamson notes that a "close examination of the relevant promissory texts" supports a "wider interpretation of the promised land" in which it is not "restricted absolutely to one geographical locale". He argues that "the map of the promised land was never seen permanently fixed, but was subject to at least some degree of expansion and redefinition."

2 Samuel 24

On David's instructions, Joab undertakes a census of Israel and Judah, travelling in an anti-clockwise direction from Gad to Gilead to Dan, then west to Sidon and Tyre, south to the cities of the Hivites and the Canaanites, to southern Judah and then returning to Jerusalem. Biblical commentator Alexander Kirkpatrick notes that the cities of Tyre and Sidon were "never occupied by the Israelites, and we must suppose either that the region traversed by the enumerators is defined as reaching up to though not including [them], or that these cities were actually visited in order to take a census of Israelites resident in them."

Ezekiel 47

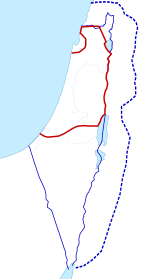

Ezekiel 47:13–20 provides a definition of borders of land in which the twelve tribes of Israel will live during the final redemption, at the end of days. The borders of the land described by the text in Ezekiel include the northern border of modern Lebanon, eastwards (the way of Hethlon) to Zedad and Hazar-enan in modern Syria; south by southwest to the area of Busra on the Syrian border (area of Hauran in Ezekiel); follows the Jordan River between the West Bank and the land of Gilead to Tamar (Ein Gedi) on the western shore of the Dead Sea; From Tamar to Meribah Kadesh (Kadesh Barnea), then along the Brook of Egypt (see debate below) to the Mediterranean Sea. The territory defined by these borders is divided into twelve strips, one for each of the twelve tribes.

Hence, Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47 define different but similar borders which include the whole of contemporary Lebanon, both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and Israel, except for the South Negev and Eilat. Small parts of Syria are also included.

From Dan to Beersheba

The common biblical phrase used to refer to the territories actually settled by the Israelites (as opposed to military conquests) is "from Dan to Beersheba" (or its variant "from Beersheba to Dan"), which occurs many times in the Bible.

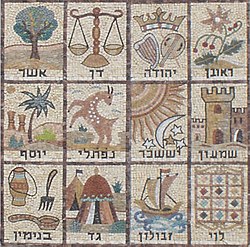

Division of tribes

The 12 tribes of Israel are divided in 1 Kings 11. In the chapter, King Solomon's sins lead to Israelites forfeiting 10 of the 12 tribes:

30 and Ahijah took hold of the new cloak he was wearing and tore it into twelve pieces. 31 Then he said to Jeroboam, "Take ten pieces for yourself, for this is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: 'See, I am going to tear the kingdom out of Solomon's hand and give you ten tribes. 32 But for the sake of my servant David and the city of Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, he will have one tribe. 33 I will do this because they have forsaken me and worshiped Ashtoreth the goddess of the Sidonians, Chemosh the god of the Moabites, and Molek the god of the Ammonites, and have not walked in obedience to me, nor done what is right in my eyes, nor kept my decrees and laws as David, Solomon's father, did.34 "'But I will not take the whole kingdom out of Solomon's hand; I have made him ruler all the days of his life for the sake of David my servant, whom I chose and who obeyed my commands and decrees. 35 I will take the kingdom from his son's hands and give you ten tribes. 36 I will give one tribe to his son so that David my servant may always have a lamp before me in Jerusalem, the city where I chose to put my Name.

— Kings 1, 11:30-11:36

Jewish beliefs

Rabbinic laws in the Land of Israel

According to Jewish religious law (halakha), some laws only apply to Jews living in the Land of Israel and some areas in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria (which are thought to be part of biblical Israel). These include agricultural laws such as the Shmita (Sabbatical year); tithing laws such as the Maaser Rishon (Levite Tithe), Maaser sheni, and Maaser ani (poor tithe); charitable practices during farming, such as pe'ah; and laws regarding taxation. One popular source lists 26 of the 613 mitzvot as contingent upon the Land of Israel. According to Menachem Lorberbaum, the consecrated borders of the Land of Israel understood by returning exiles differed from both the biblical and pre-exilic borders.

Many of the religious laws which applied in ancient times are applied in the modern State of Israel; others have not been revived, since the State of Israel does not adhere to traditional Jewish law. However, certain parts of the current territory of the State of Israel, such as the Arabah, are considered by some religious authorities to be outside the Land of Israel for purposes of Jewish law. According to these authorities, the religious laws do not apply there.

According to some Jewish religious authorities, every Jew has an obligation to dwell in the Land of Israel and may not leave except for specifically permitted reasons (e.g., to get married).

There are also many laws dealing with how to treat the land. The laws apply to all Jews, and the giving of the land itself in the covenant, applies to all Jews, including converts.

Inheritance of the promise

Traditional religious Jewish interpretation, and that of most Christian commentators, define Abraham's descendants only as Abraham's seed through his son Isaac and his grandson Jacob. Johann Friedrich Karl Keil is less clear, as he states that the covenant is through Isaac, but also notes that Ishmael's descendants, generally the Arabs, have held much of that land through time.

Modern Jewish debates on the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel concept has been evoked by the founders of the State of Israel. It often surfaces in political debates on the status of the West Bank, which is referred to in official Israeli discourse as Judea and Samaria, from the names of the two historical Israelite and Judean kingdoms. These debates frequently invoke religious principles, despite the little weight these principles typically carry in Israeli secular politics.

Ideas about the need for Jewish control of the land of Israel have been propounded by figures such as Yitzhak Ginsburg, who has written about the historical entitlement that Jews have to the whole Land of Israel. Ginsburgh's ideas about the need for Jewish control over the land has some popularity within contemporary West Bank settlements. However, there are also strong backlashes from the Jewish community regarding these ideas.

The Satmar Hasidic community in particular denounces any geographic or political establishment of Israel, deeming this establishment as directly interfering with God's plan for Jewish redemption. Joel Teitelbaum was a foremost figure in this denouncement, calling the Land and State of Israel a vehicle for idol worship, as well as a smokescreen for Satan's workings.

Christian beliefs

Inheritance of the promise

During the early 5th century, Saint Augustine of Hippo argued in his City of God that the earthly or "carnal" kingdom of Israel achieved its peak during the reigns of David and his son Solomon. He goes on to say however, that this possession was conditional: "...the Hebrew nation should remain in the same land by the succession of posterity in an unshaken state even to the end of this mortal age, if it obeyed the laws of the Lord its God."

He goes on to say that the failure of the Hebrew nation to adhere to this condition resulted in its revocation and the making of a second covenant and cites Jeremiah 31:31–32: "Behold, the days come, says the Lord, that I will make for the house of Israel, and for the house of Judah, a new testament: not according to the testament that I settled for their fathers in the day when I laid hold of their hand to lead them out of the land of Egypt; because they continued not in my testament, and I regarded them not, says the Lord."

Augustine concludes that this other promise, revealed in the New Testament, was about to be fulfilled through the incarnation of Christ: "I will give my laws in their mind, and will write them upon their hearts, and I will see to them; and I will be to them a God, and they shall be to me a people". Notwithstanding this doctrine stated by Augustine and also by the Apostle Paul in his Epistle to the Romans (Ch. 11), the phenomenon of Christian Zionism is widely noted today, especially among evangelical Protestants. Other Protestant groups and churches reject Christian Zionism on various grounds.

History

Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. Nonetheless, during two millennia of exile and with a continuous yet small Jewish presence in the land, a strong sense of bondedness exists throughout this tradition, expressed in terms of people-hood; from the very beginning, this concept was identified with that ancestral biblical land or, to use the traditional religious and modern Hebrew term, Eretz Yisrael. Religiously and culturally the area was seen broadly as a land of destiny, and always with hope for some form of redemption and return. It was later seen as a national home and refuge, intimately related to that traditional sense of people-hood, and meant to show continuity that this land was always seen as central to Jewish life, in theory if not in practice.

Ottoman era

Having already used another religious term of great importance, Zion (Jerusalem), to coin the name of their movement, being associated with the return to Zion. The term was considered appropriate for the secular Jewish political movement of Zionism to adopt at the turn of the 20th century; it was used to refer to their proposed national homeland in the area then controlled by the Ottoman Empire. As originally stated, "The aim of Zionism is to create for the Jewish people a home in Palestine secured by law."

British Mandate

The Biblical concept of Eretz Israel, and its re-establishment as a state in the modern era, was a basic tenet of the original Zionist program. This program however, saw little success until the British commitment to "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people" in the Balfour Declaration. Chaim Weizmann, as leader of the Zionist delegation, at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference presented a Zionist Statement on 3 February. Among other things, he presented a plan for development together with a map of the proposed homeland. The statement noted the Jewish historical connection with "Palestine". It also declared the Zionists' proposed borders and resources "essential for the necessary economic foundation of the country" including "the control of its rivers and their headwaters". These borders included present day Israel and the occupied territories, western Jordan, southwestern Syria and southern Lebanon "in the vicinity south of Sidon".

In 1920, the Jewish members of the first High Commissioner's advisory council objected to the Hebrew transliteration of the word "Palestine" פלשתינה (Palestina) on the ground that the traditional name was ארץ ישראל (Eretz Yisrael), but the Arab members would not agree to this designation, which in their view, had political significance. The High Commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel, himself a Zionist, decided that the Hebrew transliteration should be used, followed always by the two initial letters of "Eretz Yisrael," א״י Aleph-Yod:

He was aware that there was no other name in the Hebrew language for this land except 'Eretz-Israel'. At the same time he thought that if 'Eretz-Israel' only were used, it might not be regarded by the outside world as a correct rendering of the word 'Palestine', and in the case of passports or certificates of nationality, it might perhaps give rise to difficulties, so it was decided to print 'Palestine' in Hebrew letters and to add after it the letters 'Aleph' 'Yod', which constitute a recognised abbreviation of the Hebrew name. His Excellency still thought that this was a good compromise. Dr. Salem wanted to omit 'Aleph' 'Yod' and Mr. Yellin wanted to omit 'Palestine'. The right solution would be to retain both."

—Minutes of the meeting on November 9, 1920.

The compromise was later noted as among Arab grievances before the League's Permanent Mandate Commission. During the Mandate, the name Eretz Yisrael (abbreviated א״י Aleph-Yod), was part of the official name for the territory, when written in Hebrew. These official names for Palestine were minted on the Mandate coins and early stamps (pictured) in English, Hebrew "(פלשתינה (א״י" (Palestina E"Y) and Arabic ("فلسطين"). Consequently, in 20th-century political usage, the term "Land of Israel" usually denotes only those parts of the land which came under the British mandate.

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution (United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181(II)) recommending "to the United Kingdom, as the mandatory Power for Palestine, and to all other Members of the United Nations the adoption and implementation, with regard to the future government of Palestine, of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union." The Resolution contained a plan to partition Palestine into "Independent Arab and Jewish States and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem."

Israeli period

On 14 May 1948, the day the British Mandate over Palestine expired, the Jewish People's Council gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum, and approved a proclamation, in which it declared "the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel."

When Israel was founded in 1948, the majority Israeli Labor Party leadership, which governed for three decades after independence, accepted the partition of Mandatory Palestine into independent Jewish and Arab states as a pragmatic solution to the political and demographic issues of the territory, with the description "Land of Israel" applying to the territory of the State of Israel within the Green Line. The then opposition revisionists, who evolved into today's Likud party, however, regarded the rightful Land of Israel as Eretz Yisrael Ha-Shlema (literally, the whole Land of Israel), which came to be referred to as Greater Israel. Joel Greenberg, writing in The New York Times, relates subsequent events this way:

The seed was sown in 1977, when Menachem Begin of Likud brought his party to power for the first time in a stunning election victory over Labor. A decade before, in the 1967 war, Israeli troops had in effect undone the partition accepted in 1948 by overrunning the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Ever since, Mr. Begin had preached undying loyalty to what he called Judea and Samaria (the West Bank lands) and promoted Jewish settlement there. But he did not annex the West Bank and Gaza to Israel after he took office, reflecting a recognition that absorbing the Palestinians could turn Israel it into a binational state instead of a Jewish one.

Following the Six-Day War in 1967, the 1977 elections and the Oslo Accords, the term Eretz Israel became increasingly associated with right-wing expansionist groups who sought to conform the borders of the State of Israel with the biblical Eretz Yisrael.

As of 2022, according to the Israeli demographer Arnon Soffer, Palestinians constitute the majority of the population of Eretz Israel, 51.16% as opposed to Jews who, depending on definitions, make up between 46-47%.

Modern usage

Usage in Israeli politics

Early government usage of the term, following Israel's establishment, continued the historical link and possible Zionist intentions. In 1951–2 David Ben-Gurion wrote "Only now, after seventy years of pioneer striving, have we reached the beginning of independence in a part of our small country." Soon afterwards he wrote "It has already been said that when the State was established it held only six percent of the Jewish people remaining alive after the Nazi cataclysm. It must now be said that it has been established in only a portion of the Land of Israel. Even those who are dubious as to the restoration of the historical frontiers, as fixed and crystallised and given from the beginning of time, will hardly deny the anomaly of the boundaries of the new State." The 1955 Israeli government year-book said, "It is called the 'State of Israel' because it is part of the Land of Israel and not merely a Jewish State. The creation of the new State by no means derogates from the scope of historical Eretz Israel".

Herut and Gush Emunim were among the first Israeli political parties basing their land policies on the Biblical narrative discussed above. They attracted attention following the capture of additional territory in the 1967 Six-Day War. They argue that the West Bank should be annexed permanently to Israel for both ideological and religious reasons. This position is in conflict with the basic "land for peace" settlement formula included in UN242. The Likud party, in the platform it maintained until prior to the 2013 elections, had proclaimed its support for maintaining Jewish settlement communities in the West Bank and Gaza, as the territory is considered part of the historical land of Israel. In her 2009 bid for Prime Minister, Kadima leader Tzipi Livni used the expression, noting, "we need to give up parts of the Land of Israel", in exchange for peace with the Palestinians and to maintain Israel as a Jewish state; this drew a clear distinction with the position of her Likud rival and winner, Benjamin Netanyahu. However, soon after winning the 2009 elections, Netanyahu delivered an address at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University that was broadcast live in Israel and across parts of the Arab world, on the topic of the Middle East peace process. He endorsed for the first time the notion of a Palestinian state alongside Israel, while asserting the right to a sovereign state in Israel arises from the land being "the homeland of the Jewish people".

The Israel–Jordan Treaty of Peace, signed in 1993, led to the establishment of an agreed border between the two nations, and subsequently the state of Israel has no territorial claims in the parts of the historic Land of Israel lying east of the Jordan river.

Yom HaAliyah (Aliyah Day, Hebrew: יום העלייה) is an Israeli national holiday celebrated annually on the tenth of the Hebrew month of Nisan to commemorate the Israelites crossing the Jordan River into the Land of Israel while carrying the Ark of the Covenant.