From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Andromeda Galaxy | |

|---|---|

The Andromeda Galaxy

|

|

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Pronunciation | /ænˈdrɒmɨdə/ |

| Constellation | Andromeda |

| Right ascension | 00h 42m 44.3s[1] |

| Declination | +41° 16′ 9″[1] |

| Redshift | z = −0.001001 (minus sign indicates blueshift)[1] |

| Helio radial velocity | −301 ± 1 km/s[2] |

| Distance | 2.54 ± 0.11 Mly (778 ± 33 kpc)[2][3][4][5][6][a] |

| Type | SA(s)b[1] |

| Mass | ~1.5×1012[7] M☉ |

| Size (ly) | ~220 kly (diameter)[8] |

| Number of stars | 1 trillion (1012)[9] |

| Apparent dimensions (V) | 190′ × 60′[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.44[10][11] |

| Absolute magnitude (V) | −21.5[b][4] |

| Other designations | |

| M31, NGC 224, UGC 454, PGC 2557, 2C 56 (Core),[1] CGCG 535-17, MCG +07-02-016, IRAS 00400+4059, 2MASX J00424433+4116074, GC 116, h 50, Bode 3, Flamsteed 58, Hevelius 32, Ha 3.3, IRC +40013 | |

The Andromeda Galaxy (/ænˈdrɒmɨdə/) is a spiral galaxy approximately 780 kiloparsecs (2.5 million light-years; 2.4×1019 km) from Earth.[4] Also known as Messier 31, M31, or NGC 224, it is often referred to as the Great Andromeda Nebula in older texts. The Andromeda Galaxy is the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way, but not the nearest galaxy overall. It gets its name from the area of the sky in which it appears, the constellation of Andromeda, which was named after the mythological princess Andromeda. The Andromeda Galaxy is the largest galaxy of the Local Group, which also contains the Milky Way, the Triangulum Galaxy, and about 44 other smaller galaxies.

The Andromeda Galaxy is the most massive galaxy in the Local Group as well.[7] Despite earlier findings that suggested that the Milky Way contains more dark matter and could be the most massive in the grouping,[12] the 2006 observations by the Spitzer Space Telescope revealed that M31 contains one trillion (1012) stars:[9] at least twice the number of stars in the Milky Way, which is estimated to be 200–400 billion.[13]

The Andromeda Galaxy is estimated to be 1.5×1012 solar masses,[7] while the mass of the Milky Way is estimated to be 8.5×1011 solar masses. In comparison a 2009 study estimated that the Milky Way and M31 are about equal in mass,[14] while a 2006 study put the mass of the Milky Way at ~80% of the mass of the Andromeda Galaxy. The two galaxies are expected to collide in 3.75 billion years, eventually merging to form a giant elliptical galaxy [15] or perhaps a large disk galaxy.[16]

At 3.4, the apparent magnitude of the Andromeda Galaxy is one of the brightest of any Messier objects,[17] making it visible to the naked eye on moonless nights even when viewed from areas with moderate light pollution. Although it appears more than six times as wide as the full Moon when photographed through a larger telescope, only the brighter central region is visible to the naked eye or when viewed using binoculars or a small telescope.

Observation history

The Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi wrote a line about the chained constellation in his Book of Fixed Stars around 964, describing it as a "small cloud".[18][19] Star charts of that period have it labeled as the Little Cloud.[19] The first description of the object based on telescopic observation was given by German astronomer Simon Marius on December 15, 1612.[20] Charles Messier catalogued it as object M31 in 1764 and incorrectly credited Marius as the discoverer, unaware of Al Sufi's earlier work. In 1785, the astronomer William Herschel noted a faint reddish hue in the core region of M31. He believed it to be the nearest of all the "great nebulae" and based on the color and magnitude of the nebula, he incorrectly guessed that it was no more than 2,000 times the distance of Sirius.[21]

William Huggins in 1864 observed the spectrum of M31 and noted that it differed from a gaseous nebula.[22] The spectra of M31 displayed a continuum of frequencies, superimposed with dark absorption lines that help identify the chemical composition of an object. The Andromeda nebula was very similar to the spectra of individual stars, and from this it was deduced that M31 had a stellar nature. In 1885, a supernova (known as S Andromedae) was seen in M31, the first and so far only one observed in that galaxy. At the time M31 was considered to be a nearby object, so the cause was thought to be a much less luminous and unrelated event called a nova, and was named accordingly "Nova 1885".[23]

The first photographs of M31 were taken in 1887 by Isaac Roberts from his private observatory in Sussex, England. The long-duration exposure allowed the spiral structure of the galaxy to be seen for the first time.[25] However, at the time this object was still commonly believed to be a nebula within our galaxy, and Roberts mistakenly believed that M31 and similar spiral nebulae were actually solar systems being formed, with the satellites nascent planets.[citation needed] The radial velocity of this object with respect to our solar system was measured in 1912 by Vesto Slipher at the Lowell Observatory, using spectroscopy. The result was the largest velocity recorded at that time, at 300 kilometres per second (190 mi/s), moving in the direction of the Sun.[26]

Island universe

In 1917, American astronomer Heber Curtis observed a nova within M31. Searching the photographic record, 11 more novae were discovered. Curtis noticed that these novae were, on average, 10 magnitudes fainter than those that occurred elsewhere in the sky. As a result he was able to come up with a distance estimate of 500,000 light-years (3.2×1010 AU). He became a proponent of the so-called "island universes" hypothesis, which held that spiral nebulae were actually independent galaxies.[27]

In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis took place, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the universe. To support his claim that the Great Andromeda Nebula was an external galaxy, Curtis also noted the appearance of dark lanes resembling the dust clouds in our own Galaxy, as well as the significant Doppler shift. In 1922 Ernst Öpik presented a method to estimate the distance of M31 using the measured velocities of its stars. His result put the Andromeda Nebula far outside our Galaxy at a distance of about 450,000 parsecs (1,500,000 ly).[28] Edwin Hubble settled the debate in 1925 when he identified extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos of M31. These were made using the 2.5-metre (100-in) Hooker telescope, and they enabled the distance of Great Andromeda Nebula to be determined. His measurement demonstrated conclusively that this feature was not a cluster of stars and gas within our Galaxy, but an entirely separate galaxy located a significant distance from our own.[29]

M31 plays an important role in galactic studies, since it is the nearest spiral galaxy (although not the nearest galaxy). In 1943 Walter Baade was the first person to resolve stars in the central region of the Andromeda Galaxy. Based on his observations of this galaxy, he was able to discern two distinct populations of stars based on their metallicity, naming the young, high velocity stars in the disk Type I and the older, red stars in the bulge Type II. This nomenclature was subsequently adopted for stars within the Milky Way, and elsewhere. (The existence of two distinct populations had been noted earlier by Jan Oort.)[31] Baade also discovered that there were two types of Cepheid variables, which resulted in a doubling of the distance estimate to M31, as well as the remainder of the Universe.[32]

Radio emission from the Andromeda Galaxy was first detected by Hanbury Brown and Cyril Hazard at Jodrell Bank Observatory using the 218-ft Transit Telescope, and was announced in 1950[33][34] (Earlier observations were made by radio astronomy pioneer Grote Reber in 1940, but were inconclusive, and were later shown to be an order of magnitude too high). The first radio maps of the galaxy were made in the 1950s by John Baldwin and collaborators at the Cambridge Radio Astronomy Group.[35] The core of the Andromeda Galaxy is called 2C 56 in the 2C radio astronomy catalogue. In 2009, the first planet may have been discovered in the Andromeda Galaxy. This candidate was detected using a technique called microlensing, which is caused by the deflection of light by a massive object.[36]

General

The measured distance to the Andromeda Galaxy was doubled in 1953 when it was discovered that there is another, dimmer type of Cepheid. In the 1990s, measurements of both standard red giants as well as red clump stars from the Hipparcos satellite measurements were used to calibrate the Cepheid distances.[37][38]

Formation and history

According to a team of astronomers reporting in 2010, M31 was formed out of the collision of two smaller galaxies between 5 and 9 billion years ago.[39]A paper published in 2012[40] has outlined M31's basic history since its birth. According to it, Andromeda was born roughly 10 billion years ago from the merger of many smaller protogalaxies, leading to a galaxy smaller than the one we see today.

The most important event in M31's past history was the merger mentioned above that took place 8 billion years ago. This violent collision formed most of its (metal-rich) galactic halo and extended disk and during that epoch Andromeda's star formation would have been very high, to the point of becoming a luminous infrared galaxy for roughly 100 million years.

M31 and the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) had a very close passage 2–4 billion years ago. This event produced high levels of star formation across the Andromeda Galaxy's disk – even some globular clusters – and disturbed M33's outer disk.

While there has been activity during the last 2 billion years, this has been much lower than during the past. During this epoch, star formation throughout M31's disk decreased to the point of nearly shutting down, then increased again relatively recently. There have been interactions with satellite galaxies like M32, M110, or others that have already been absorbed by M31. These interactions have formed structures like Andromeda's Giant Stellar Stream. A merger roughly 100 million years ago is believed to be responsible for a counter-rotating disk of gas found in the center of M31 as well as the presence there of a relatively young (100 million years old) stellar population.

Recent distance estimate

At least four distinct techniques have been used to measure distances to the Andromeda Galaxy.In 2003, using the infrared surface brightness fluctuations (I-SBF) and adjusting for the new period-luminosity value of Freedman et al. 2001 and using a metallicity correction of −0.2 mag dex−1 in (O/H), an estimate of 2.57 ± 0.06 million light-years (1.625×1011 ± 3.8×109 AU) was derived.

Using the Cepheid variable method, an estimate of 2.51 ± 0.13 million light-years (770 ± 40 kpc) was reported in 2004.[2][3]

In 2005 Ignasi Ribas (CSIC, Institute for Space Studies of Catalonia (IEEC)) and colleagues announced the discovery of an eclipsing binary star in the Andromeda Galaxy. The binary star, designated M31VJ00443799+4129236,[c] has two luminous and hot blue stars of types O and B. By studying the eclipses of the stars, which occur every 3.54969 days, astronomers were able to measure their sizes. Knowing the sizes and temperatures of the stars, they were able to measure their absolute magnitude. When the visual and absolute magnitudes are known, the distance to the star can be measured. The stars lie at a distance of 2.52×106 ± 0.14×106 ly (1.594×1011 ± 8.9×109 AU) and the whole Andromeda Galaxy at about 2.5×106 ly (1.6×1011 AU).[4] This new value is in excellent agreement with the previous, independent Cepheid-based distance value.

M31 is close enough that the Tip of the Red Giant Branch (TRGB) method may also be used to estimate its distance. The estimated distance to M31 using this technique in 2005 yielded 2.56×106 ± 0.08×106 ly (1.619×1011 ± 5.1×109 AU).[5]

Averaged together, all these distance measurements give a combined distance estimate of 2.54×106 ± 0.11×106 ly (1.606×1011 ± 7.0×109 AU).[a] Based upon the above distance, the diameter of M31 at the widest point is estimated to be 220 ± 3 kly (67,450 ± 920 pc). Applying trigonometry (arctangent), that figures to extending at an apparent 3.18° angle in the sky.

Mass and luminosity estimates

Mass

Mass estimates for the Andromeda Galaxy's halo (including dark matter) give a value of approximately 1.5×1012 M☉[7] (or 1.5 trillion solar masses) compared to 8×1011 M☉ for the Milky Way. This contradicts earlier measurements, that seem to indicate that Andromeda and the Milky Way are almost equal in mass. Even so, M31's spheroid actually has a higher stellar density than that of the Milky Way[41] and its galactic stellar disk is about twice the size of that of the Milky Way.[8]Luminosity

M31 appears to have significantly more common stars than the Milky Way, and the estimated luminosity of M31, ~2.6×1010 L☉, is about 25% higher than that of our own galaxy.[42] However, the galaxy has a high inclination as seen from Earth and its interstellar dust absorbs an unknown amount of light, so it is difficult to estimate its actual brightness and other authors have given other values for the luminosity of the Andromeda Galaxy (including to propose it is the second brightest galaxy within a radius of 10 mega parsecs of the Milky Way, after the Sombrero Galaxy[43]) , the most recent estimation (done in 2010 with the help of Spitzer Space Telescope) suggesting an absolute magnitude (in the blue) of −20.89 (that with a color index of +0.63 translates to an absolute visual magnitude of −21.52,[b] compared to −20.9 for the Milky Way), and a total luminosity in that wavelength of 3.64×1010 L☉[44]The rate of star formation in the Milky Way is much higher, with M31 producing only about one solar mass per year compared to 3–5 solar masses for the Milky Way. The rate of supernovae in the Milky Way is also double that of M31.[45] This suggests that M31 once experienced a great star formation phase, but is now in a relative state of quiescence, whereas the Milky Way is experiencing more active star formation.[42] Should this continue, the luminosity in the Milky Way may eventually overtake that of M31.

According to recent studies, like the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy lies in what in the galaxy color–magnitude diagram is known as the green valley, a region populated by galaxies in transition from the blue cloud (galaxies actively forming new stars) to the red sequence (galaxies that lack star formation). Star formation activity in green valley galaxies is slowing as they run out of star-forming gas in the interstellar medium. In simulated galaxies with similar properties, star formation will typically have been extinguished within about five billion years from now, even accounting for the expected, short-term increase in the rate of star formation due to the collision between Andromeda and the Milky Way.[46]

Structure

The Andromeda Galaxy seen in infrared by the Spitzer Space Telescope, one of NASA's four Great Space Observatories

Image of the Andromeda Galaxy taken by Spitzer in infrared, 24 micrometres (Credit:NASA/JPL–Caltech/K. Gordon, University of Arizona)

A Swift Tour of Andromeda Galaxy

A Galaxy Evolution Explorer image of the Andromeda Galaxy. The bands of blue-white making up the galaxy's striking rings are neighborhoods that harbor hot, young, massive stars. Dark blue-grey lanes of cooler dust show up starkly against these bright rings, tracing the regions where star formation is currently taking place in dense cloudy cocoons. When observed in visible light, Andromeda’s rings look more like spiral arms. The ultraviolet view shows that these arms more closely resemble the ring-like structure previously observed in infrared wavelengths with NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Astronomers using Spitzer interpreted these rings as evidence that the galaxy was involved in a direct collision with its neighbor, M32, more than 200 million years ago.

Based on its appearance in visible light, the Andromeda Galaxy is classified as an SA(s)b galaxy in the de Vaucouleurs–Sandage extended classification system of spiral galaxies.[1] However, data from the 2MASS survey showed that the bulge of M31 has a box-like appearance, which implies that the galaxy is actually a barred spiral galaxy like the Milky Way, with the Andromeda Galaxy's bar viewed almost directly along its long axis.[47]

In 2005, astronomers used the Keck telescopes to show that the tenuous sprinkle of stars extending outward from the galaxy is actually part of the main disk itself.[8] This means that the spiral disk of stars in M31 is three times larger in diameter than previously estimated. This constitutes evidence that there is a vast, extended stellar disk that makes the galaxy more than 220,000 light-years (67,000 pc) in diameter. Previously, estimates of the Andromeda Galaxy's size ranged from 70,000 to 120,000 light-years (21,000 to 37,000 pc) across.

The galaxy is inclined an estimated 77° relative to the Earth (where an angle of 90° would be viewed directly from the side). Analysis of the cross-sectional shape of the galaxy appears to demonstrate a pronounced, S-shaped warp, rather than just a flat disk.[48] A possible cause of such a warp could be gravitational interaction with the satellite galaxies near M31. The galaxy M33 could be responsible for some warp in M31's arms, though more precise distances and radial velocities are required.

Spectroscopic studies have provided detailed measurements of the rotational velocity of M31 at various radii from the core. In the vicinity of the core, the rotational velocity climbs to a peak of 225 kilometres per second (140 mi/s) at a radius of 1,300 light-years (82,000,000 AU), then descends to a minimum at 7,000 light-years (440,000,000 AU) where the rotation velocity may be as low as 50 kilometres per second (31 mi/s). Thereafter the velocity steadily climbs again out to a radius of 33,000 light-years (2.1×109 AU), where it reaches a peak of 250 kilometres per second (160 mi/s). The velocities slowly decline beyond that distance, dropping to around 200 kilometres per second (120 mi/s) at 80,000 light-years (5.1×109 AU). These velocity measurements imply a concentrated mass of about 6×109 M☉ in the nucleus. The total mass of the galaxy increases linearly out to 45,000 light-years (2.8×109 AU), then more slowly beyond that radius.[49]

The spiral arms of M31 are outlined by a series of H II regions, first studied in great detail by Walter Baade and described by him as resembling "beads on a string". his studies show two spiral arms that appear to be tightly wound, although they are more widely spaced than in our galaxy.[50] His descriptions of the spiral structure, as each arm crosses the major axis of M31, are as follows[51]§pp1062[52]§pp92:

| Arms (N=cross M31's major axis at north, S=cross M31's major axis at south) | Distance from center (arcminutes) (N*/S*) | Distance from center (kpc) (N*/S*) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1/S1 | 3.4/1.7 | 0.7/0.4 | Dust arms with no OB associations of HII regions. |

| N2/S2 | 8.0/10.0 | 1.7/2.1 | Dust arms with some OB associations. |

| N3/S3 | 25/30 | 5.3/6.3 | As per N2/S2, but with some HII regions too. |

| N4/S4 | 50/47 | 11/9.9 | Large numbers of OB associations, HII regions, and little dust. |

| N5/S5 | 70/66 | 15/14 | As per N4/S4 but much fainter. |

| N6/S6 | 91/95 | 19/20 | Loose OB associations. No dust visible. |

| N7/S7 | 110/116 | 23/24 | As per N6/S6 but fainter and inconspicuous. |

Since the Andromeda Galaxy is seen close to edge-on, however, the studies of its spiral structure are difficult. While as stated above rectified images of the galaxy seem to show a fairly normal spiral galaxy with the arms wound up in a clockwise direction, exhibiting two continuous trailing arms that are separated from each other by a minimum of about 13,000 light-years (820,000,000 AU) and that can be followed outward from a distance of roughly 1,600 light-years (100,000,000 AU) from the core, other alternative spiral structures have been proposed such as a single spiral arm[53] or a flocculent[54] pattern of long, filamentary, and thick spiral arms.[1][55]

The most likely cause of the distortions of the spiral pattern is thought to be interaction with galaxy satellites M32 and M110.[56] This can be seen by the displacement of the neutral hydrogen clouds from the stars.[57]

In 1998, images from the European Space Agency's Infrared Space Observatory demonstrated that the overall form of the Andromeda Galaxy may be transitioning into a ring galaxy. The gas and dust within M31 is generally formed into several overlapping rings, with a particularly prominent ring formed at a radius of 32,000 light-years (2.0×109 AU) from the core.[58] This ring is hidden from visible light images of the galaxy because it is composed primarily of cold dust.

Later studies with the help of the Spitzer Space Telescope showed how Andromeda's spiral structure in the infrared appears to be composed of two spiral arms that emerge from a central bar and continue beyond the large ring mentioned above. Those arms, however, are not continuous and have a segmented structure.[56]

Close examination of the inner region of M31 with the same telescope also showed a smaller dust ring that is believed to have been caused by the interaction with M32 more than 200 million years ago. Simulations show that the smaller galaxy passed through the disk of the galaxy in Andromeda along the latter's polar axis. This collision stripped more than half the mass from the smaller M32 and created the ring structures in M31.[59] It is the co-existence of the long-known large ring-like feature in the gas of Messier 31, together with this newly discovered inner ring-like structure, offset from the barycenter, that suggested a nearly head-on collision with the satellite M32, a milder version of the Cartwheel encounter.[60]

Studies of the extended halo of M31 show that it is roughly comparable to that of the Milky Way, with stars in the halo being generally "metal-poor", and increasingly so with greater distance.[41] This evidence indicates that the two galaxies have followed similar evolutionary paths. They are likely to have accreted and assimilated about 100–200 low-mass galaxies during the past 12 billion years.[61] The stars in the extended halos of M31 and the Milky Way may extend nearly one-third the distance separating the two galaxies.

Nucleus

M31 is known to harbor a dense and compact star cluster at its very center. In a large telescope it creates a visual impression of a star embedded in the more diffuse surrounding bulge. The luminosity of the nucleus is in excess of the most luminous globular clusters.[citation needed]

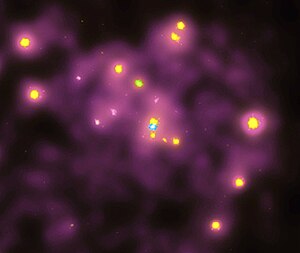

Chandra X-ray telescope image of the center of M31. A number of X-ray sources, likely X-ray binary stars, within Andromeda's central region appear as yellowish dots. The blue source at the center is at the position of the supermassive black hole.

In 1991 Tod R. Lauer used WFPC, then on board the Hubble Space Telescope, to image M31's inner nucleus. The nucleus consists of two concentrations separated by 1.5 parsecs (4.9 ly). The brighter concentration, designated as P1, is offset from the center of the galaxy. The dimmer concentration, P2, falls at the true center of the galaxy and contains a black hole measured at 3–5 × 107 M☉ in 1993,[62] and at 1.1–2.3 × 108 M☉ in 2005.[63] The velocity dispersion of material around it is measured to be ≈ 160 km/s.[64]

Scott Tremaine has proposed that the observed double nucleus could be explained if P1 is the projection of a disk of stars in an eccentric orbit around the central black hole.[65] The eccentricity is such that stars linger at the orbital apocenter, creating a concentration of stars. P2 also contains a compact disk of hot, spectral class A stars. The A stars are not evident in redder filters, but in blue and ultraviolet light they dominate the nucleus, causing P2 to appear more prominent than P1.[66]

While at the initial time of its discovery it was hypothesized that the brighter portion of the double nucleus was the remnant of a small galaxy "cannibalized" by M31,[67] this is no longer considered a viable explanation, largely because such a nucleus would have an exceedingly short lifetime due to tidal disruption by the central black hole. While this could be partially resolved if P1 had its own black hole to stabilize it, the distribution of stars in P1 does not suggest that there is a black hole at its center.[65]

Discrete sources

Apparently, by late 1968, no X-rays had been detected from the Andromeda Galaxy.[68] A balloon flight on October 20, 1970, set an upper limit for detectable hard X-rays from M31.[69]

Multiple X-ray sources have since been detected in the Andromeda Galaxy, using observations from the ESA's XMM-Newton orbiting observatory. Robin Barnard et al. hypothesized that these are candidate black holes or neutron stars, which are heating incoming gas to millions of kelvins and emitting X-rays. The spectrum of the neutron stars is the same as the hypothesized black holes, but can be distinguished by their masses.[70]

There are approximately 460 globular clusters associated with the Andromeda Galaxy.[71] The most massive of these clusters, identified as Mayall II, nicknamed Globular One, has a greater luminosity than any other known globular cluster in the Local Group of galaxies.[72] It contains several million stars, and is about twice as luminous as Omega Centauri, the brightest known globular cluster in the Milky Way. Globular One (or G1) has several stellar populations and a structure too massive for an ordinary globular. As a result, some consider G1 to be the remnant core of a dwarf galaxy that was consumed by M31 in the distant past.[73] The globular with the greatest apparent brightness is G76 which is located in the south-west arm's eastern half.[19] Another massive globular cluster -named 037-B327-, discovered in 2006 as is heavily reddened by the Andromeda Galaxy's interstellar dust, was thought to be more massive than G1 and the largest cluster of the Local Group;[74] however other studies have shown is actually similar in properties to G1.[75]

Unlike the globular clusters of the Milky Way, which show a relatively low age dispersion, Andromeda's globular clusters have a much larger range of ages: from systems as old as the galaxy itself to much younger systems, with ages between a few hundred million years to five billion years[76]

In 2005, astronomers discovered a completely new type of star cluster in M31. The new-found clusters contain hundreds of thousands of stars, a similar number of stars that can be found in globular clusters. What distinguishes them from the globular clusters is that they are much larger — several hundred light-years across — and hundreds of times less dense. The distances between the stars are, therefore, much greater within the newly discovered extended clusters.[77]

In the year 2012, a microquasar, a radio burst emanating from a smaller black hole, was detected in the Andromeda Galaxy. The progenitor black hole was located near the galactic center and had about 10

. Discovered through a data collected by the ESA's XMM-Newton probe, and subsequently observed by NASA's Swift and Chandra, the Very Large Array, and the Very Long Baseline Array, the microquasar was the first observed within the Andromeda Galaxy and the first outside of the Milky Way Galaxy.[78]

. Discovered through a data collected by the ESA's XMM-Newton probe, and subsequently observed by NASA's Swift and Chandra, the Very Large Array, and the Very Long Baseline Array, the microquasar was the first observed within the Andromeda Galaxy and the first outside of the Milky Way Galaxy.[78]Satellites

Like the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy has satellite galaxies, consisting of 14 known dwarf galaxies. The best known and most readily observed satellite galaxies are M32 and M110. Based on current evidence, it appears that M32 underwent a close encounter with M31 (Andromeda) in the past. M32 may once have been a larger galaxy that had its stellar disk removed by M31, and underwent a sharp increase of star formation in the core region, which lasted until the relatively recent past.[79]M110 also appears to be interacting with M31, and astronomers have found in the halo of M31 a stream of metal-rich stars that appear to have been stripped from these satellite galaxies.[80] M110 does contain a dusty lane, which may indicate recent or ongoing star formation.[81]

In 2006 it was discovered that nine of these galaxies lie along a plane that intersects the core of the Andromeda Galaxy, rather than being randomly arranged as would be expected from independent interactions. This may indicate a common tidal origin for the satellites.[82]