From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Tibet (

|

|||||||||

| "Greater Tibet" as claimed by Tibetan exile groups | |||||||||

| Tibetan autonomous areas, designed by China | |||||||||

| Tibet Autonomous Region, within China | |||||||||

| Chinese-controlled, claimed by India as part of Aksai Chin | |||||||||

| Indian-controlled, claimed by China as part of the Tibet A.R. | |||||||||

| Other areas historically within the Tibetan cultural sphere | |||||||||

Tibet emerged in the 7th century as a unified empire, but it soon divided into a variety of territories. The bulk of western and central Tibet (Ü-Tsang) was often at least nominally unified under a series of Tibetan governments in Lhasa, Shigatse, or nearby locations; these governments were at various times under Mongol and Chinese overlordship. The eastern regions of Kham and Amdo often maintained a more decentralized indigenous political structure, being divided among a number of small principalities and tribal groups, while also often falling more directly under Chinese rule; most of this area was eventually incorporated into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Qinghai. The current borders of Tibet were generally established in the 18th century.[1]

Following the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912, Qing soldiers were disarmed and escorted out of Tibet Area (Ü-Tsang). The region subsequently declared its independence in 1913, without recognition by the following Chinese Republican government.[2] Later Lhasa took control of the western part of Xikang Province, China. The region maintained its autonomy until 1951 when, following the Invasion of Tibet, Tibet became unified into the People's Republic of China, and the previous Tibetan government was abolished in 1959 after a failed uprising.[3] Today, the People's Republic of China governs western and central Tibet as the Tibet Autonomous Region; while the eastern areas are now mostly ethnic autonomous prefectures within Sichuan, Qinghai and other neighbouring provinces. There are tensions regarding Tibet's political status[4] and dissident groups which are active in exile.[5] It is also said that Tibetan activists in Tibet have been arrested or tortured.[6]

The economy of Tibet is dominated by subsistence agriculture, though tourism has become a growing industry in Tibet in recent decades. The dominant religion in Tibet is Tibetan Buddhism, in addition there is Bön which was the indigenous religion of Tibet before the arrival of Buddhism in the 7th century CE (Bön is now similar to Tibetan Buddhism[7]) though there are also Muslim and Christian minorities. Tibetan Buddhism is a primary influence on the art, music, and festivals of the region. Tibetan architecture reflects Chinese and Indian influences. Staple foods in Tibet are roasted barley, yak meat, and butter tea.

Names

The Tibetan name for their land, Bod བོད་, means "Tibet" or "Tibetan Plateau", although it originally meant the central region around Lhasa, now known in Tibetan as Ü. The Standard Tibetan pronunciation of Bod, [pʰøʔ˨˧˨], is transcribed Bhö in Tournadre Phonetic Transcription, Bö in the THDL system, and Poi in Tibetan Pinyin. Some scholars believe the first written reference to Bod "Tibet" was the ancient Bautai people recorded in the Egyptian Greek works Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century CE) and Geographia (Ptolemy, 2nd century CE),[8] itself from the Sanskrit form Bhauṭṭa of the Indian geographical tradition.[9]The modern Mandarin exonym for the ethnic Tibetan region is Zangqu (Chinese: 藏区; pinyin: Zàngqū), which derives by metonymy from the Tsang region around Shigatse (plus the addition of a Chinese suffix, 区 qū, which means "area, district, region, ward"). Tibetan people, language, and culture regardless of where they are from are referred to as Zang (Chinese: 藏; pinyin: Zàng), although the geographical term Xīzàng is often limited to the Tibet Autonomous Region. The term Xīzàng was coined during the Qing Dynasty in the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor (1796–1820) through the addition of a prefix meaning "west" (西 xī) to Zang.

The best-known medieval Chinese name for Tibet is Tubo (Chinese: 吐蕃 also written as 土蕃 or 土番; pinyin: Tǔbō or Tǔfān). This name first appears in Chinese characters as 土番 in the 7th-century (Li Tai) and as 吐蕃 in the 10th-century (Old Book of Tang describing 608–609 emissaries from Tibetan King Namri Songtsen to Emperor Yang of Sui). In the Middle Chinese spoken during that period, as reconstructed by William H. Baxter, 土番 was pronounced thux-phjon and 吐蕃 was pronounced thux-pjon (with the x representing tone).[10]

Other pre-modern Chinese names for Tibet include Wusiguo (Chinese: 烏斯國; pinyin: Wūsīguó; cf. Tibetan dbus, Ü, [wyʔ˨˧˨]), Wusizang (Chinese: 烏斯藏; pinyin: wūsīzàng, cf. Tibetan dbus-gtsang, Ü-Tsang), Tubote (Chinese: 圖伯特; pinyin: Túbótè), and Tanggute (Chinese: 唐古忒; pinyin: Tánggǔtè, cf. Tangut). American Tibetologist Elliot Sperling has argued in favor of a recent tendency by some authors writing in Chinese to revive the term Tubote (simplified Chinese: 图伯特; traditional Chinese: 圖伯特; pinyin: Túbótè) for modern use in place of Xizang, on the grounds that Tubote more clearly includes the entire Tibetan plateau rather than simply the Tibet Autonomous Region.[citation needed]

The English word Tibet or Thibet dates back to the 18th century.[11] Historical linguists generally agree that "Tibet" names in European languages are loanwords from Semitic Ṭībat orTūbātt (طيبة، توبات) (טובּה, טובּת), itself deriving from Turkic Töbäd; literally: "The Heights" (plural of töbän).[12]

Language

Linguists generally classify the Tibetan language as a Tibeto-Burman language of the Sino-Tibetan language family although the boundaries between 'Tibetan' and certain other Himalayan languages can be unclear. According to Matthew Kapstein:From the perspective of historical linguistics, Tibetan most closely resembles Burmese among the major languages of Asia. Grouping these two together with other apparently related languages spoken in the Himalayan lands, as well as in the highlands of Southeast Asia and the Sino-Tibetan frontier regions, linguists have generally concluded that there exists a Tibeto-Burman family of languages. More controversial is the theory that the Tibeto-Burman family is itself part of a larger language family, called Sino-Tibetan, and that through it Tibetan and Burmese are distant cousins of Chinese.[13]

The language has numerous regional dialects which are generally not mutually intelligible. It is employed throughout the Tibetan plateau and Bhutan and is also spoken in parts of Nepal and northern India, such as Sikkim. In general, the dialects of central Tibet (including Lhasa), Kham, Amdo and some smaller nearby areas are considered Tibetan dialects. Other forms, particularly Dzongkha, Sikkimese, Sherpa, and Ladakhi, are considered by their speakers, largely for political reasons, to be separate languages. However, if the latter group of Tibetan-type languages are included in the calculation then 'greater Tibetan' is spoken by approximately 6 million people across the Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan is also spoken by approximately 150,000 exile speakers who have fled from modern-day Tibet to India and other countries.

Although spoken Tibetan varies according to the region, the written language, based on Classical Tibetan, is consistent throughout. This is probably due to the long-standing influence of the Tibetan empire, whose rule embraced (and extended at times far beyond) the present Tibetan linguistic area, which runs from northern Pakistan in the west to Yunnan and Sichuan in the east, and from north of Qinghai Lake south as far as Bhutan. The Tibetan language has its own script which it shares with Ladakhi and Dzongkha, and which is derived from the ancient Indian Brāhmī script.[14]

Starting in 2001, the local deaf sign languages of Tibet were standardized, and Tibetan Sign Language is now being promoted across the country.

History

King Songtsän Gampo

Humans inhabited the Tibetan Plateau at least 21,000 years ago.[15] This population was largely replaced around 3,000 BP by Neolithic immigrants from northern China. However, there is a partial genetic continuity between the Paleolithic inhabitants and the contemporary Tibetan populations.[15]

The earliest Tibetan historical texts identify the Zhang Zhung culture as a people who migrated from the Amdo region into what is now the region of Guge in western Tibet.[16] Zhang Zhung is considered to be the original home of the Bön religion.[17] By the 1st century BCE, a neighboring kingdom arose in the Yarlung valley, and the Yarlung king, Drigum Tsenpo, attempted to remove the influence of the Zhang Zhung by expelling the Zhang's Bön priests from Yarlung.[18] He was assassinated and Zhang Zhung continued its dominance of the region until it was annexed by Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century. Prior to Songtsän Gampo, the kings of Tibet were more mythological than factual, and there is insufficient evidence of their existence.[19]

Tibetan Empire

The history of a unified Tibet begins with the rule of Songtsän Gampo (604–650 CE) who united parts of the Yarlung River Valley and founded the Tibetan Empire. He also brought in many reforms and Tibetan power spread rapidly creating a large and powerful empire. It is traditionally considered that his first wife was the Princess of Nepal, Bhrikuti, and that she played a great role in establishment of Buddhism in Tibet. In 640 he married Princess Wencheng, the niece of the powerful Chinese emperor Taizong of Tang China.[20]

Under the next few Tibetan kings, Buddhism became established as the state religion and Tibetan power increased even further over large areas of Central Asia, while major inroads were made into Chinese territory, even reaching the Tang's capital Chang'an (modern Xi'an) in late 763.[21] However, the Tibetan occupation of Chang'an only lasted for fifteen days, after which they were defeated by Tang and its ally, the Turkic Uyghur Khaganate.

The Kingdom of Nanzhao (in Yunnan and neighbouring regions) remained under Tibetan control from 750 to 794, when they turned on their Tibetan overlords and helped the Chinese inflict a serious defeat on the Tibetans.[22]

In 747, the hold of Tibet was loosened by the campaign of general Gao Xianzhi, who tried to re-open the direct communications between Central Asia and Kashmir. By 750 the Tibetans had lost almost all of their central Asian possessions to the Chinese. However, after Gao Xianzhi's defeat by the Arabs and Qarluqs at the Battle of Talas (751) and the subsequent civil war (755), Chinese influence decreased rapidly and Tibetan influence resumed.

At its height in the 780's to 790's the Tibetan empire reached its highest glory when it ruled and controlled a territory stretching from modern day Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan.

In 821/822 CE Tibet and China signed a peace treaty. A bilingual account of this treaty, including details of the borders between the two countries, is inscribed on a stone pillar which stands outside the Jokhang temple in Lhasa.[23] Tibet continued as a Central Asian empire until the mid-9th century, when a civil war over succession led to the collapse of imperial Tibet. The period that followed is known traditionally as the Era of Fragmentation, when political control over Tibet became divided between regional warlords and tribes with no dominant centralized authority.

Yuan dynasty

Tibet in 1734. Royaume de Thibet ("Kingdom of Tibet") in la Chine, la Tartarie Chinoise, et le Thibet ("China, Chinese Tartary, and Tibet") on a 1734 map by Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville, based on earlier Jesuit maps.

Mitchell’s 1864 map of Tibet and China.

Tibet in 1892 during the Manchu Qing dynasty.

The Mongolian Yuan dynasty, through the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs, or Xuanzheng Yuan, ruled Tibet through a top-level administrative department. One of the department's purposes was to select a dpon-chen ('great administrator'), usually appointed by the lama and confirmed by the Mongol emperor in Beijing.[24] The Sakya lama retained a degree of autonomy, acting as the political authority of the region, while the dpon-chen held administrative and military power. Mongol rule of Tibet remained separate from the main provinces of China, but the region existed under the administration of the Yuan dynasty. If the Sakya lama ever came into conflict with the dpon-chen, the dpon-chen had the authority to send Chinese troops into the region.[24]

Tibet retained nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols managed a structural and administrative[25] rule over the region, reinforced by the rare military intervention. This existed as a "diarchic structure" under the Yuan emperor, with power primarily in favor of the Mongols.[24] Mongolian prince Khuden gained temporal power in Tibet in the 1240s and sponsored Sakya Pandita, whose seat became the capital of Tibet.

Yuan control over the region ended with the Ming overthrow of the Yuan and Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen's revolt against the Mongols.[26] Following the uprising, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen founded the Phagmodrupa dynasty, and sought to reduce Yuan influences over Tibetan culture and politics.[27]

Phagmodrupa, Rinpungpa and Tsangpa Dynasties

Between 1346 and 1354, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen toppled the Sakya and founded the Phagmodrupa Dynasty. The following 80 years saw the founding of the Gelug school (also known as Yellow Hats) by the disciples of Je Tsongkhapa, and the founding of the important Ganden, Drepung and Sera monasteries near Lhasa. However, internal strife within the dynasty and the strong localism of the various fiefs and political-religious factions led to a long series of internal conflicts. The minister family Rinpungpa, based in Tsang (West Central Tibet), dominated politics after 1435. In 1565 they were overthrown by the Tsangpa Dynasty of Shigatse which expanded its power in different directions of Tibet in the following decades and favoured the Karma Kagyu sect.Rise of Ganden Phodrang

In 1578, Altan Khan of the Tümed Mongols gave Sonam Gyatso, a high lama of the Gelugpa school, the name Dalai Lama, Dalai being the Mongolian translation of the Tibetan name Gyatso "Ocean".[28]The 5th Dalai Lama is known for unifying the Tibetan heartland under the control of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, after defeating the rival Kagyu and Jonang sects and the secular ruler, the Tsangpa prince, in a prolonged civil war. His efforts were successful in part because of aid from Güshi Khan, the Oirat leader of the Khoshut Khanate. With Güshi Khan as a largely uninvolved overlord, the 5th Dalai Lama and his intimates established a civil administration which is referred to by historians as the Lhasa state. This Tibetan regime or government is also referred to as the Ganden Phodrang.

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty placed Amdo under their control in 1724, and incorporated eastern Kham into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.[29] Meanwhile, the Qing government sent a resident commissioner, called an Amban, to Lhasa. In 1750 the Ambans and majority of the Han Chinese and Manchus living in Lhasa were killed in a riot, and Qing troops arrived quickly and suppressed the rebels in the next year. Like the preceding Yuan dynasty, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty exerted military and administrative control of the region, while granting it a degree of political autonomy. The Qing commander publicly executed a number of supporters of the rebels, and, as in 1723 and 1728, made changes in the political structure and drew up a formal organization plan. The Qing now restored the Dalai Lama as ruler leading government called Kashag[30] but elevated the role of Amban to include more direct involvement in Tibetan internal affairs. At the same time the Qing took steps to counterbalance the power of the aristocracy by adding officials recruited from the clergy to key posts.[31]For several decades, peace reigned in Tibet, but in 1792 the Qing Qianlong Emperor sent a large Chinese army into Tibet to push the invading Nepalese out. This prompted yet another Qing reorganization of the Tibetan government, this time through a written plan called the "Twenty-Nine Regulations for Better Government in Tibet". Qing military garrisons staffed with Qing troops were now also established near the Nepalese border.[32] Tibet was dominated by the Manchus in various stages in the 18th century, and the years immediately following the 1792 regulations were the peak of the Qing imperial commissioners' authority; but there was no attempt to make Tibet a Chinese province.[33]

In 1834 the Sikh Empire invaded and annexed Ladakh, a culturally Tibetan region that was an independent kingdom at the time. Seven years later a Sikh army led by General Zorawar Singh invaded western Tibet from Ladakh, starting the Sino-Sikh War. A Qing-Tibetan army repelled the invaders but was in turn defeated when it chased the Sikhs into Ladakh. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Chushul between the Chinese and Sikh empires.[34]

As the Qing dynasty weakened, its authority over Tibet also gradually declined and by the mid-19th century, its influence was minuscule. Qing authority over Tibet had become more symbolic than real by the late 19th century,[35][36][37][38] although in the 1860s the Tibetans still chose for reasons of their own to emphasize the empire's symbolic authority and make it seem substantial.[39]

This period also saw some contacts with Jesuits and Capuchins from Europe, and in 1774 a Scottish nobleman, George Bogle, came to Shigatse to investigate trade for the British East India Company.[40] However, by the 19th century the situation of foreigners in Tibet grew more tenuous. The British Empire was encroaching from northern India into the Himalayas, the Emirate of Afghanistan and the Russian Empire were expanding into Central Asia and each power became suspicious of the others' intentions in Tibet.

Ragyapas, an outcast group, early 20th century. Their hereditary occupation included disposal of corpses and leather work.

In 1904, a British expedition to Tibet, spurred in part by a fear that Russia extended its power into Tibet as part of The Great Game, invaded the country and hoping that negotiations with the 13th Dalai Lama would be more effective than with Chinese representatives.[41] When the British-led invasion reached Tibet, an armed confrontation with the ethnic Tibetans resulted in the Massacre of Chumik Shenko,[42] after which Francis Younghusband imposed a treaty in 1904 known as the Treaty of Lhasa which was subsequently repudiated, and was succeeded by a 1906 treaty[43] signed between Britain and China.

In 1910, the Qing government sent a military expedition of its own under Zhao Erfeng to establish direct Manchu-Chinese rule and deposed the Dalai Lama in an imperial edict, who fled to British India. Zhao Erfeng defeated the Tibetan military conclusively and expelled the Dalai Lama's forces from the province. However, his actions were unpopular, and there was much animosity against him for his mistreatment of civilians and disregard for local culture.

Post-Qing period

After the Xinhai Revolution (1911–12) toppled the Qing dynasty and the last Qing troops were escorted out of Tibet, the new Republic of China apologized for the actions of the Qing and offered to restore the Dalai Lama's title.[44] The Dalai Lama refused any Chinese title, and declared himself ruler of an independent Tibet.[45] In 1913 Tibet and Mongolia concluded treaty on mutual recognition.[46] For the next 36 years, the 13th Dalai Lama and the regents who succeeded him governed Tibet. During this time, Tibet fought Chinese warlords for control of the ethnically Tibetan areas in Xikang and Qinghai (parts of Kham and Amdo) along the upper reaches of the Yangtze River.[29] In 1914 the Tibetan government signed the Simla Accord with Britain, ceding the South Tibet region to British India. The Chinese government denounced the agreement as illegal.[47][48]When the regents in the 1930s and 1940s displayed negligence in affairs, the Kuomintang Government of the Republic of China used this to their advantage to expand their reach into the territory.[49]

From 1950 to present

Thamzing of Tibetan woman circa 1958

Emerging with control over most of mainland China after the Chinese Civil War, the People's Republic of China incorporated Tibet in 1950 and negotiated the Seventeen Point Agreement with the newly enthroned 14th Dalai Lama's government, affirming the People's Republic of China's sovereignty but granting the area autonomy. Subsequently, on his journey into exile, the 14th Dalai Lama completely repudiated the agreement, which he has repeated on many occasions.[50][51]

After the Dalai Lama government fled to Dharamsala, India, during the 1959 Tibetan Rebellion, it established a rival government-in-exile. Afterwards, the Central People's Government in Beijing renounced the agreement and began implementation of the halted social and political reforms.[52] During the Great Leap Forward between 200,000 and 1,000,000 Tibetans died,[53] and approximately 6,000 monasteries were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.[54] In 1962 China and India fought a brief war over the disputed South Tibet and Aksai Chin regions. Although China won the war, Chinese troops withdrew north of the McMahon Line, effectively ceding South Tibet to India.[48]

In 1980, General Secretary and reformist Hu Yaobang visited Tibet, and ushered in a period of social, political, and economic liberalization.[55] At the end of the decade, however analogously to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, monks in the Drepung and Sera monasteries started protesting for independence, and so the government halted reforms and started an anti-separatist campaign.[55] Human rights organisations have been critical of the Beijing and Lhasa governments' approach to human rights in the region when cracking down on separatist convulsions that have occurred around monasteries and cities, most recently in the 2008 Tibetan unrest.

Geography

Tibet is located on the Tibetan Plateau, the world's highest region.

All of modern China, including Tibet, is considered a part of East Asia.[56] Historically, some European sources also considered parts of Tibet to lie in Central Asia. Tibet is west of the Central China plain, and within mainland China, Tibet is regarded as part of 西部 (Xībù), a term usually translated by Chinese media as "the Western section", meaning "Western China".

Tibet has some of the world's tallest mountains, with several of them making the top ten list. Mount Everest, at 8,848 metres (29,029 ft), is the highest mountain on earth, located on the border with Nepal. Several major rivers have their source in the Tibetan Plateau (mostly in present-day Qinghai Province). These include Yangtze, Yellow River, Indus River, Mekong, Ganges, Salween and the Yarlung Tsangpo River (Brahmaputra River).[57] The Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, along the Yarlung Tsangpo River, is among the deepest and longest canyons in the world.

Tibet has been called the "Water Tower" of Asia, and China is investing heavily in water projects in Tibet.[58][59]

The Indus and Brahmaputra rivers originate from a lake (Tib: Tso Mapham) in Western Tibet, near Mount Kailash. The mountain is a holy pilgrimage site for both Hindus and Tibetans. The Hindus consider the mountain to be the abode of Lord Shiva. The Tibetan name for Mt. Kailash is Khang Rinpoche. Tibet has numerous high-altitude lakes referred to in Tibetan as tso or co. These include Qinghai Lake, Lake Manasarovar, Namtso, Pangong Tso, Yamdrok Lake, Siling Co, Lhamo La-tso, Lumajangdong Co, Lake Puma Yumco, Lake Paiku, Lake Rakshastal, Dagze Co and Dong Co. The Qinghai Lake (Koko Nor) is the largest lake in the People's Republic of China.

The atmosphere is severely dry nine months of the year, and average annual snowfall is only 18 inches (46 cm), due to the rain shadow effect. Western passes receive small amounts of fresh snow each year but remain traversable all year round. Low temperatures are prevalent throughout these western regions, where bleak desolation is unrelieved by any vegetation bigger than a low bush, and where wind sweeps unchecked across vast expanses of arid plain. The Indian monsoon exerts some influence on eastern Tibet. Northern Tibet is subject to high temperatures in the summer and intense cold in the winter.

Cultural Tibet consists of several regions. These include Amdo (A mdo) in the northeast, which is administratively part of the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan. Kham (Khams) in the southeast encompasses parts of western Sichuan, northern Yunnan, southern Qinghai and the eastern part of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Ü-Tsang (dBus gTsang) (Ü in the center, Tsang in the center-west, and Ngari (mNga' ris) in the far west) covered the central and western portion of Tibet Autonomous Region.[60]

Tibetan cultural influences extend to the neighboring states of Bhutan, Nepal, regions of India such as Sikkim, Ladakh, Lahaul, and Spiti, in addition to designated Tibetan autonomous areas in adjacent Chinese provinces.

Cities, towns and villages

There are over 800 settlements in Tibet. Lhasa is Tibet's traditional capital and the capital of Tibet Autonomous Region. It contains two world heritage sites – the Potala Palace and Norbulingka, which were the residences of the Dalai Lama. Lhasa contains a number of significant temples and monasteries, including Jokhang and Ramoche Temple.

Shigatse is the second largest city in the Tibet AR, west of Lhasa. Gyantse and Qamdo are also amongst the largest.

Other cities and towns in cultural Tibet include Shiquanhe (Ali), Nagchu, Bamda, Rutog, Nyingchi, Nedong, Coqên, Barkam, Sakya, Gartse, Pelbar, Lhatse, and Tingri; in Sichuan, Kangding (Dartsedo); in Qinghai, Jyekundo (Yushu), Machen, and Golmud; in India, Tawang, Leh, and Gangtok.

Government

The central region of Tibet is an autonomous region within China, the Tibet Autonomous Region. The Tibet Autonomous Region is a province-level entity of the People's Republic of China. It is governed by a People's Government, led by a Chairman. In practice, however, the Chairman is subordinate to the branch secretary of the Communist Party of China. As a matter of convention, the Chairman has almost always been an ethnic Tibetan, while the party secretary has always been ethnically non-Tibetan.[61]The theocratic government

Prior to assertion of Chinese control over Tibet it was a feudal theocracy headed by the Dalai Lama or a regency and administered by the Kashag, a council of four, and 400–500 officials drawn from the traditional Tibetan aristocracy, Tibetan monasteries, and middle-class families of Lhasa.[62]Economy

The Tibetan yak is an integral part of Tibetan life

The Tibetan economy is dominated by subsistence agriculture. Due to limited arable land, the primary occupation of the Tibetan Plateau is raising livestock, such as sheep, cattle, goats, camels, yaks, dzo, and horses. The main crops grown are barley, wheat, buckwheat, rye, potatoes, and assorted fruits and vegetables. Tibet is ranked the lowest among China’s 31 provinces[63] on the Human Development Index according to UN Development Programme data.[64] In recent years, due to increased interest in Tibetan Buddhism, tourism has become an increasingly important sector, and is actively promoted by the authorities.[65] Tourism brings in the most income from the sale of handicrafts. These include Tibetan hats, jewelry (silver and gold), wooden items, clothing, quilts, fabrics, Tibetan rugs and carpets. The Central People's Government exempts Tibet from all taxation and provides 90% of Tibet's government expenditures.[66][67][68][69] However most of this investment goes to pay migrant workers who do not settle in Tibet and send much of their income home to other provinces.[70]

The Qingzang railway linking the Tibet Autonomous Region to Qinghai Province was opened in 2006, but not without controversy.[71][72][73]

In January 2007, the Chinese government issued a report outlining the discovery of a large mineral deposit under the Tibetan Plateau.[74] The deposit has an estimated value of $128 billion and may double Chinese reserves of zinc, copper, and lead. The Chinese government sees this as a way to alleviate the nation's dependence on foreign mineral imports for its growing economy. However, critics worry that mining these vast resources will harm Tibet's fragile ecosystem and undermine Tibetan culture.[74]

On January 15, 2009, China announced the construction of Tibet’s first expressway, a 37.9-kilometre stretch of controlled-access highway in southwestern Lhasa. The project will cost 1.55 billion yuan (US$227 million).[75]

From January 18–20, 2010 a national conference on Tibet and areas inhabited by Tibetans in Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu and Qinghai was held in China and a substantial plan to improve development of the areas was announced.

The conference was attended by General secretary Hu Jintao, Wu Bangguo, Wen Jiabao, Jia Qinglin, Li Changchun, Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, He Guoqiang and Zhou Yongkang, all members of CPC Politburo Standing Committee signaling the commitment of senior Chinese leaders to development of Tibet and ethnic Tibetan areas. The plan calls for improvement of rural Tibetan income to national standards by 2020 and free education for all rural Tibetan children. China has invested 310 billion yuan (about 45.6 billion U.S. dollars) in Tibet since 2001. "Tibet's GDP was expected to reach 43.7 billion yuan in 2009, up 170 percent from that in 2000 and posting an annual growth of 12.3 percent over the past nine years."[76]

Development Zone

The State Council approved Tibet Lhasa Economic and Technological Development Zone as a state-level development zone in 2001. It is located in the western suburbs of Lhasa, the capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region. It is 50 km away from the Gonggar Airport, and 2 km away from Lhasa Railway Station and 2 km away from 318 national highway.The zone has a planned area of 5.46 square kilometers and is divided into two zones. Zone A developed a land area of 2.51 square kilometers for construction purposes. It is a flat zone, and has the natural conditions for good drainage.[77]

Demographics

Historically, the population of Tibet consisted of primarily ethnic Tibetans and some other ethnic groups. According to tradition the original ancestors of the Tibetan people, as represented by the six red bands in the Tibetan flag, are: the Se, Mu, Dong, Tong, Dru and Ra. Other traditional ethnic groups with significant population or with the majority of the ethnic group reside in Tibet (excluding disputed area with India) include Bai people, Blang, Bonan, Dongxiang, Han, Hui people, Lhoba, Lisu people, Miao, Mongols, Monguor (Tu people), Menba (Monpa), Mosuo, Nakhi, Qiang, Nu people, Pumi, Salar, and Yi people.

The proportion of the non-Tibetan population in Tibet is disputed. On the one hand, the Central Tibetan Administration of the Dalai Lama, accuses China of actively swamping Tibet with migrants in order to alter Tibet's demographic makeup.[78] On the other hand, according to the 2010 Chinese census ethnic Tibetans comprise 90% of a total population of 3 million in the Tibet Autonomous Region.[79] Exact population numbers probably depend on how temporary migrants are counted.[citation needed]

Culture

Religion

Tibetan Buddhism

Buddhist monks in Drepung Monastery

Religion is extremely important to the Tibetans and has a strong influence over all aspects of their lives. Bön is the ancient religion of Tibet, but has been almost eclipsed by Tibetan Buddhism, a distinctive form of Mahayana and Vajrayana, which was introduced into Tibet from the Sanskrit Buddhist tradition of northern India.[80] Tibetan Buddhism is practiced not only in Tibet but also in Mongolia, parts of northern India, the Buryat Republic, the Tuva Republic, and in the Republic of Kalmykia and some other parts of China. During China's Cultural Revolution, nearly all Tibet's monasteries were ransacked and destroyed by the Red Guards.[81][82][83] A few monasteries have begun to rebuild since the 1980s (with limited support from the Chinese government) and greater religious freedom has been granted – although it is still limited. Monks returned to monasteries across Tibet and monastic education resumed even though the number of monks imposed is strictly limited.[81][84][85] Before the 1950s, between 10 and 20% of males in Tibet were monks.[86]

Tibetan Buddhism has four main traditions (the suffix pa is comparable to "er" in English):

- Gelug(pa), Way of Virtue, also known casually as Yellow Hat, whose spiritual head is the Ganden Tripa and whose temporal head is the Dalai Lama. Successive Dalai Lamas ruled Tibet from the mid-17th to mid-20th centuries. This order was founded in the 14th to 15th centuries by Je Tsongkhapa, based on the foundations of the Kadampa tradition. Tsongkhapa was renowned for both his scholasticism and his virtue. The Dalai Lama belongs to the Gelugpa school, and is regarded as the embodiment of the Bodhisattva of Compassion.[87]

- Kagyu(pa), Oral Lineage. This contains one major subsect and one minor subsect. The first, the Dagpo Kagyu, encompasses those Kagyu schools that trace back to Gampopa. In turn, the Dagpo Kagyu consists of four major sub-sects: the Karma Kagyu, headed by a Karmapa, the Tsalpa Kagyu, the Barom Kagyu, and Pagtru Kagyu. The once-obscure Shangpa Kagyu, which was famously represented by the 20th-century teacher Kalu Rinpoche, traces its history back to the Indian master Niguma, sister of Kagyu lineage holder Naropa. This is an oral tradition which is very much concerned with the experiential dimension of meditation. Its most famous exponent was Milarepa, an 11th-century mystic.

- Nyingma(pa), The Ancient Ones. This is the oldest, the original order founded by Padmasambhava.

- Sakya(pa), Grey Earth, headed by the Sakya Trizin, founded by Khon Konchog Gyalpo, a disciple of the great translator Drokmi Lotsawa. Sakya Pandita 1182–1251 CE was the great grandson of Khon Konchog Gyalpo. This school emphasizes scholarship.

Islam

Muslims have been living in Tibet since as early as the 8th or 9th century. In Tibetan cities, there are small communities of Muslims, known as Kachee (Kache), who trace their origin to immigrants from three main regions: Kashmir (Kachee Yul in ancient Tibetan), Ladakh and the Central Asian Turkic countries. Islamic influence in Tibet also came from Persia. After 1959 a group of Tibetan Muslims made a case for Indian nationality based on their historic roots to Kashmir and the Indian government declared all Tibetan Muslims Indian citizens later on that year.[88] Other Muslim ethnic groups who have long inhabited Tibet include Hui, Salar, Dongxiang and Bonan. There is also a well established Chinese Muslim community (gya kachee), which traces its ancestry back to the Hui ethnic group of China.

Christianity

The first Christians documented to have reached Tibet were the Nestorians, of whom various remains and inscriptions have been found in Tibet. They were also present at the imperial camp of Möngke Khan at Shira Ordo, where they debated in 1256 with Karma Pakshi (1204/6-83), head of the Karma Kagyu order.[89][90] Desideri, who reached Lhasa in 1716, encountered Armenian and Russian merchants.[91]Roman Catholic Jesuits and Capuchins arrived from Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. Portuguese missionaries Jesuit Father Antonio de Andrade and Brother Manuel Marques first reached the kingdom of Gelu in western Tibet in 1624 and was welcomed by the royal family who allowed them to build a church later on.[92][93] By 1627, there were about a hundred local converts in the Guge kingdom.[94] Later on, Christianity was introduced to Rudok, Ladakh and Tsang and was welcomed by the ruler of the Tsang kingdom, where Andrade and his fellows established a Jesuit outpost at Shigatse in 1626.[95]

In 1661 another Jesuit, Johann Grueber, crossed Tibet from Sining to Lhasa (where he spent a month), before heading on to Nepal.[96] He was followed by others who actually built a church in Lhasa. These included the Jesuit Father Ippolito Desideri, 1716–1721, who gained a deep knowledge of Tibetan culture, language and Buddhism, and various Capuchins in 1707–1711, 1716–1733 and 1741–1745,[97] Christianity was used by some Tibetan monarchs and their courts and the Karmapa sect lamas to counterbalance the influence of the Gelugpa sect in the 17th century until in 1745 when all the missionaries were expelled at the lama's insistence.[98][99][100][101][102][103]

In 1877, the Protestant James Cameron from the China Inland Mission walked from Chongqing to Batang in Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan province, and "brought the Gospel to the Tibetan people." Beginning in the 20th century, in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan, a large number of Lisu people and some Yi and Nu people converted to Christianity. Famous earlier missionaries include James O. Fraser, Alfred James Broomhall and Isobel Kuhn of the China Inland Mission, among others who were active in this area.[104][105]

Proselytising has been illegal in China since 1949. But as of 2013, many Christian missionaries were reported to be active in Tibet with the tacit approval of Chinese authorities, who view the missionaries as a counterforce to Tibetan Buddhism or as a boon to the local economy.[106]

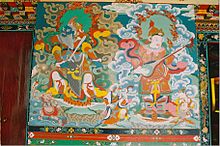

Tibetan art

Tibetan representations of art are intrinsically bound with Tibetan Buddhism and commonly depict deities or variations of Buddha in various forms from bronze Buddhist statues and shrines, to highly colorful thangka paintings and mandalas.

Architecture

Tibetan architecture contains Chinese and Indian influences, and reflects a deeply Buddhist approach. The Buddhist wheel, along with two dragons, can be seen on nearly every Gompa in Tibet. The design of the Tibetan Chörtens can vary, from roundish walls in Kham to squarish, four-sided walls in Ladakh.The most distinctive feature of Tibetan architecture is that many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south, and are often made out of a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth. Little fuel is available for heat or lighting, so flat roofs are built to conserve heat, and multiple windows are constructed to let in sunlight. Walls are usually sloped inwards at 10 degrees as a precaution against the frequent earthquakes in this mountainous area.

Standing at 117 meters in height and 360 meters in width, the Potala Palace is the most important example of Tibetan architecture. Formerly the residence of the Dalai Lama, it contains over one thousand rooms within thirteen stories, and houses portraits of the past Dalai Lamas and statues of the Buddha. It is divided between the outer White Palace, which serves as the administrative quarters, and the inner Red Quarters, which houses the assembly hall of the Lamas, chapels, 10,000 shrines, and a vast library of Buddhist scriptures. The Potala Palace is a World Heritage Site, as is Norbulingka, the former summer residence of the Dalai Lama.

Music

The music of Tibet reflects the cultural heritage of the trans-Himalayan region, centered in Tibet but also known wherever ethnic Tibetan groups are found in India, Bhutan, Nepal and further abroad. First and foremost Tibetan music is religious music, reflecting the profound influence of Tibetan Buddhism on the culture.Tibetan music often involves chanting in Tibetan or Sanskrit, as an integral part of the religion. These chants are complex, often recitations of sacred texts or in celebration of various festivals. Yang chanting, performed without metrical timing, is accompanied by resonant drums and low, sustained syllables. Other styles include those unique to the various schools of Tibetan Buddhism, such as the classical music of the popular Gelugpa school, and the romantic music of the Nyingmapa, Sakyapa and Kagyupa schools.[107]

Nangma dance music is especially popular in the karaoke bars of the urban center of Tibet, Lhasa. Another form of popular music is the classical gar style, which is performed at rituals and ceremonies. Lu are a type of songs that feature glottal vibrations and high pitches. There are also epic bards who sing of Gesar, who is a hero to ethnic Tibetans.

Festivals

Tibet has various festivals which are commonly performed to worship the Buddha[citation needed] throughout the year. Losar is the Tibetan New Year Festival. Preparations for the festive event are manifested by special offerings to family shrine deities, painted doors with religious symbols, and other painstaking jobs done to prepare for the event. Tibetans eat Guthuk (barley noodle soup with filling) on New Year's Eve with their families. The Monlam Prayer Festival follows it in the first month of the Tibetan calendar, falling between the fourth and the eleventh days of the first Tibetan month. It involves dancing and participating in sports events, as well as sharing picnics. The event was established in 1049 by Tsong Khapa, the founder of the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama's order.