From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The three-dimensional Euclidean space R3 is a vector space, and lines and planes passing through the origin are vector subspaces in R3.

Linear algebra is the branch of mathematics concerning vector spaces and linear mappings between such spaces. It includes the study of lines, planes, and subspaces, but is also concerned with properties common to all vector spaces.

The set of points with coordinates that satisfy a linear equation form a hyperplane in an n-dimensional space. The conditions under which a set of n hyperplanes intersect in a single point is an important focus of study in linear algebra. Such an investigation is initially motivated by a system of linear equations containing several unknowns. Such equations are naturally represented using the formalism of matrices and vectors.[1][2]

Linear algebra is central to both pure and applied mathematics. For instance, abstract algebra arises by relaxing the axioms of a vector space, leading to a number of generalizations. Functional analysis studies the infinite-dimensional version of the theory of vector spaces. Combined with calculus, linear algebra facilitates the solution of linear systems of differential equations.

Techniques from linear algebra are also used in analytic geometry, engineering, physics, natural sciences, computer science, computer animation, and the social sciences (particularly in economics). Because linear algebra is such a well-developed theory, nonlinear mathematical models are sometimes approximated by linear models.

History

The study of linear algebra first emerged from the study of determinants, which were used to solve systems of linear equations. Determinants were used by Leibniz in 1693, and subsequently, Gabriel Cramer devised Cramer's Rule for solving linear systems in 1750. Later, Gauss further developed the theory of solving linear systems by using Gaussian elimination, which was initially listed as an advancement in geodesy.[3]The study of matrix algebra first emerged in England in the mid-1800s. In 1844 Hermann Grassmann published his “Theory of Extension” which included foundational new topics of what is today called linear algebra. In 1848, James Joseph Sylvester introduced the term matrix, which is Latin for "womb". While studying compositions of linear transformations, Arthur Cayley was led to define matrix multiplication and inverses. Crucially, Cayley used a single letter to denote a matrix, thus treating a matrix as an aggregate object. He also realized the connection between matrices and determinants, and wrote "There would be many things to say about this theory of matrices which should, it seems to me, precede the theory of determinants".[3]

In 1882, Hüseyin Tevfik Pasha wrote the book titled "Linear Algebra".[4][5] The first modern and more precise definition of a vector space was introduced by Peano in 1888;[3] by 1900, a theory of linear transformations of finite-dimensional vector spaces had emerged. Linear algebra first took its modern form in the first half of the twentieth century, when many ideas and methods of previous centuries were generalized as abstract algebra. The use of matrices in quantum mechanics, special relativity, and statistics helped spread the subject of linear algebra beyond pure mathematics. The development of computers led to increased research in efficient algorithms for Gaussian elimination and matrix decompositions, and linear algebra became an essential tool for modelling and simulations.[3]

The origin of many of these ideas is discussed in the articles on determinants and Gaussian elimination.

Educational history

Linear algebra first appeared in graduate textbooks in the 1940s and in undergraduate textbooks in the 1950s.[6] Following work by the School Mathematics Study Group, U.S. high schools asked 12th grade students to do "matrix algebra, formerly reserved for college" in the 1960s.[7] In France during the 1960s, educators attempted to teach linear algebra through affine dimensional vector spaces in the first year of secondary school. This was met with a backlash in the 1980s that removed linear algebra from the curriculum.[8] In 1993, the U.S.-based Linear Algebra Curriculum Study Group recommended that undergraduate linear algebra courses be given an application-based "matrix orientation" as opposed to a theoretical orientation.[9]Scope of study

Vector spaces

The main structures of linear algebra are vector spaces. A vector space over a field F is a set V together with two binary operations. Elements of V are called vectors and elements of F are called scalars. The first operation, vector addition, takes any two vectors v and w and outputs a third vector v + w. The second operation, scalar multiplication, takes any scalar a and any vector v and outputs a new vector av. The operations of addition and multiplication in a vector space must satisfy the following axioms.[10] In the list below, let u, v and w be arbitrary vectors in V, and a and b scalars in F.| Axiom | Signification |

| Associativity of addition | u + (v + w) = (u + v) + w |

| Commutativity of addition | u + v = v + u |

| Identity element of addition | There exists an element 0 ∈ V, called the zero vector, such that v + 0 = v for all v ∈ V. |

| Inverse elements of addition | For every v ∈ V, there exists an element −v ∈ V, called the additive inverse of v, such that v + (−v) = 0 |

| Distributivity of scalar multiplication with respect to vector addition | a(u + v) = au + av |

| Distributivity of scalar multiplication with respect to field addition | (a + b)v = av + bv |

| Compatibility of scalar multiplication with field multiplication | a(bv) = (ab)v [nb 1] |

| Identity element of scalar multiplication | 1v = v, where 1 denotes the multiplicative identity in F. |

The first four axioms are those of V being an abelian group under vector addition. Vector spaces may be diverse in nature, for example, containing functions, polynomials or matrices. Linear algebra is concerned with properties common to all vector spaces.

Linear transformations

Similarly as in the theory of other algebraic structures, linear algebra studies mappings between vector spaces that preserve the vector-space structure. Given two vector spaces V and W over a field F, a linear transformation (also called linear map, linear mapping or linear operator) is a mapAdditionally for any vectors u, v ∈ V and scalars a, b ∈ F:

Linear transformations have geometric significance. For example, 2 × 2 real matrices denote standard planar mappings that preserve the origin.

Subspaces, span, and basis

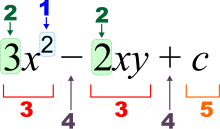

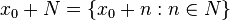

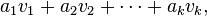

Again, in analogue with theories of other algebraic objects, linear algebra is interested in subsets of vector spaces that are themselves vector spaces; these subsets are called linear subspaces. For example, both the range and kernel of a linear mapping are subspaces, and are thus often called the range space and the nullspace; these are important examples of subspaces. Another important way of forming a subspace is to take a linear combination of a set of vectors v1, v2, …, vk:A linear combination of any system of vectors with all zero coefficients is the zero vector of V. If this is the only way to express the zero vector as a linear combination of v1, v2, …, vk then these vectors are linearly independent. Given a set of vectors that span a space, if any vector w is a linear combination of other vectors (and so the set is not linearly independent), then the span would remain the same if we remove w from the set. Thus, a set of linearly dependent vectors is redundant in the sense that there will be a linearly independent subset which will span the same subspace. Therefore, we are mostly interested in a linearly independent set of vectors that spans a vector space V, which we call a basis of V. Any set of vectors that spans V contains a basis, and any linearly independent set of vectors in V can be extended to a basis.[11] It turns out that if we accept the axiom of choice, every vector space has a basis;[12] nevertheless, this basis may be unnatural, and indeed, may not even be constructible. For instance, there exists a basis for the real numbers considered as a vector space over the rationals, but no explicit basis has been constructed.

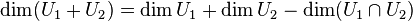

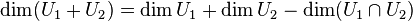

Any two bases of a vector space V have the same cardinality, which is called the dimension of V. The dimension of a vector space is well-defined by the dimension theorem for vector spaces. If a basis of V has finite number of elements, V is called a finite-dimensional vector space. If V is finite-dimensional and U is a subspace of V, then dim U ≤ dim V. If U1 and U2 are subspaces of V, then

.[13]

.[13]

Matrix theory

A particular basis {v1, v2, …, vn} of V allows one to construct a coordinate system in V: the vector with coordinates (a1, a2, …, an) is the linear combinationThere is an important distinction between the coordinate n-space Rn and a general finite-dimensional vector space V. While Rn has a standard basis {e1, e2, …, en}, a vector space V typically does not come equipped with such a basis and many different bases exist (although they all consist of the same number of elements equal to the dimension of V).

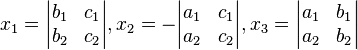

One major application of the matrix theory is calculation of determinants, a central concept in linear algebra. While determinants could be defined in a basis-free manner, they are usually introduced via a specific representation of the mapping; the value of the determinant does not depend on the specific basis. It turns out that a mapping has an inverse if and only if the determinant has an inverse (every non-zero real or complex number has an inverse[15]). If the determinant is zero, then the nullspace is nontrivial. Determinants have other applications, including a systematic way of seeing if a set of vectors is linearly independent (we write the vectors as the columns of a matrix, and if the determinant of that matrix is zero, the vectors are linearly dependent). Determinants could also be used to solve systems of linear equations (see Cramer's rule), but in real applications, Gaussian elimination is a faster method.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

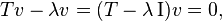

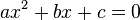

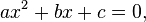

In general, the action of a linear transformation may be quite complex. Attention to low-dimensional examples gives an indication of the variety of their types. One strategy for a general n-dimensional transformation T is to find "characteristic lines" that are invariant sets under T. If v is a non-zero vector such that Tv is a scalar multiple of v, then the line through 0 and v is an invariant set under T and v is called a characteristic vector or eigenvector. The scalar λ such that Tv = λv is called a characteristic value or eigenvalue of T.To find an eigenvector or an eigenvalue, we note that

Inner-product spaces

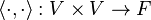

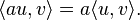

Besides these basic concepts, linear algebra also studies vector spaces with additional structure, such as an inner product. The inner product is an example of a bilinear form, and it gives the vector space a geometric structure by allowing for the definition of length and angles. Formally, an inner product is a map- Conjugate symmetry:

- Linearity in the first argument:

-

with equality only for v = 0.

with equality only for v = 0.

Two vectors are orthogonal if

. An orthonormal basis is a basis where all basis vectors have length 1 and are orthogonal to each other. Given any finite-dimensional vector space, an orthonormal basis could be found by the Gram–Schmidt procedure. Orthonormal bases are particularly nice to deal with, since if v = a1 v1 + ... + an vn, then

. An orthonormal basis is a basis where all basis vectors have length 1 and are orthogonal to each other. Given any finite-dimensional vector space, an orthonormal basis could be found by the Gram–Schmidt procedure. Orthonormal bases are particularly nice to deal with, since if v = a1 v1 + ... + an vn, then  .

.The inner product facilitates the construction of many useful concepts. For instance, given a transform T, we can define its Hermitian conjugate T* as the linear transform satisfying

Some main useful theorems

- A matrix is invertible, or non-singular, if and only if the linear map represented by the matrix is an isomorphism.

- Any vector space over a field F of dimension n is isomorphic to Fn as a vector space over F.

- Corollary: Any two vector spaces over F of the same finite dimension are isomorphic to each other.

- A linear map is an isomorphism if and only if the determinant is nonzero.

Applications

Because of the ubiquity of vector spaces, linear algebra is used in many fields of mathematics, natural sciences, computer science, and social science. Below are just some examples of applications of linear algebra.Solution of linear systems

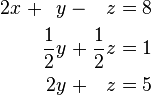

Linear algebra provides the formal setting for the linear combination of equations used in the Gaussian method. Suppose the goal is to find and describe the solution(s), if any, of the following system of linear equations:In the example, x is eliminated from L2 by adding (3/2)L1 to L2. x is then eliminated from L3 by adding L1 to L3. Formally:

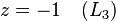

The last part, back-substitution, consists of solving for the known in reverse order. It can thus be seen that

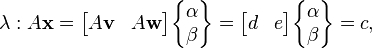

We can, in general, write any system of linear equations as a matrix equation:

. If the number of variables equal the number of equations, then we can characterize when the system has a unique solution: since N is trivial if and only if det A ≠ 0, the equation has a unique solution if and only if det A ≠ 0.[18]

. If the number of variables equal the number of equations, then we can characterize when the system has a unique solution: since N is trivial if and only if det A ≠ 0, the equation has a unique solution if and only if det A ≠ 0.[18]Least-squares best fit line

The least squares method is used to determine the best fit line for a set of data.[19] This line will minimize the sum of the squares of the residuals.Fourier series expansion

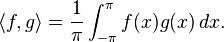

Fourier series are a representation of a function f: [−π, π] → R as a trigonometric series:The space of all functions that can be represented by a Fourier series form a vector space (technically speaking, we call functions that have the same Fourier series expansion the "same" function, since two different discontinuous functions might have the same Fourier series). Moreover, this space is also an inner product space with the inner product

; that is,

; that is,Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is highly inspired by notions in linear algebra. In quantum mechanics, the physical state of a particle is represented by a vector, and observables (such as momentum, energy, and angular momentum) are represented by linear operators on the underlying vector space. More concretely, the wave function of a particle describes its physical state and lies in the vector space L2 (the functions φ: R3 → C such that is finite), and it evolves according to the Schrödinger equation. Energy is represented as the operator

is finite), and it evolves according to the Schrödinger equation. Energy is represented as the operator  , where V is the potential energy. H is also known as the Hamiltonian operator. The eigenvalues of H represents the possible energies that can be observed. Given a particle in some state φ, we can expand φ into a linear combination of eigenstates of H. The component of H in each eigenstate determines the probability of measuring the corresponding eigenvalue, and the measurement forces the particle to assume that eigenstate (wave function collapse).

, where V is the potential energy. H is also known as the Hamiltonian operator. The eigenvalues of H represents the possible energies that can be observed. Given a particle in some state φ, we can expand φ into a linear combination of eigenstates of H. The component of H in each eigenstate determines the probability of measuring the corresponding eigenvalue, and the measurement forces the particle to assume that eigenstate (wave function collapse).Geometric introduction

Many of the principles and techniques of linear algebra can be seen in the geometry of lines in a real two dimensional plane E. When formulated using vectors and matrices the geometry of points and lines in the plane can be extended to the geometry of points and hyperplanes in high-dimensional spaces.Point coordinates in the plane E are ordered pairs of real numbers, (x,y), and a line is defined as the set of points (x,y) that satisfy the linear equation[20]

,

,

Homogeneous coordinates identify the plane E with the z = 1 plane in three dimensional space. The x−y coordinates in E are obtained from homogeneous coordinates y = (y1, y2, y3) by dividing by the third component (if it is nonzero) to obtain y = (y1/y3, y2/y3, 1).

The linear equation, λ, has the important property, that if x1 and x2 are homogeneous coordinates of points on the line, then the point αx1 + βx2 is also on the line, for any real α and β.

Now consider the equations of the two lines λ1 and λ2,

It is interesting to consider the case of three lines, λ1, λ2 and λ3, which yield the matrix equation,

Introduction to linear transformations

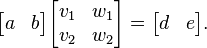

Another way to approach linear algebra is to consider linear functions on the two dimensional real plane E=R2. Here R denotes the set of real numbers. Let x=(x, y) be an arbitrary vector in E and consider the linear function λ: E→R, given byConsider the linear functional a little more carefully. Let i=(1,0) and j =(0,1) be the natural basis vectors on E, so that x=xi+yj. It is now possible to see that

This is true for any pair of vectors used to define coordinates in E. Suppose we select a non-orthogonal non-unit vector basis v and w to define coordinates of vectors in E. This means a vector x has coordinates (α,β), such that x=αv+βw. Then, we have the linear functional

Coordinates relative to a basis

This leads to the question of how to determine the coordinates of a vector x relative to a general basis v and w in E. Assume that we know the coordinates of the vectors, x, v and w in the natural basis i=(1,0) and j =(0,1). Our goal is two find the real numbers α, β, so that x=αv+βw, that isInverse image

The set of points in the plane E that map to the same image in R under the linear functional λ define a line in E. This line is the image of the inverse map, λ−1: R→E. This inverse image is the set of the points x=(x, y) that solve the equation,In order to solve the equation, we first recognize that only one of the two unknowns (x,y) can be determined, so we select y to be determined, and rearrange the equation

The vector p defines the intersection of the line with the y-axis, known as the y-intercept. The vector h satisfies the homogeneous equation,

The set of points of a linear functional that map to zero define the kernel of the linear functional. The line can be considered to be the set of points h in the kernel translated by the vector p.[20][22]

Since linear algebra is a successful theory, its methods have been developed and generalized in other parts of mathematics. In module theory, one replaces the field of scalars by a ring. The concepts of linear independence, span, basis, and dimension (which is called rank in module theory) still make sense. Nevertheless, many theorems from linear algebra become false in module theory. For instance, not all modules have a basis (those that do are called free modules), the rank of a free module is not necessarily unique, not every linearly independent subset of a module can be extended to form a basis, and not every subset of a module that spans the space contains a basis.

In multilinear algebra, one considers multivariable linear transformations, that is, mappings that are linear in each of a number of different variables. This line of inquiry naturally leads to the idea of the dual space, the vector space V∗ consisting of linear maps f: V → F where F is the field of scalars. Multilinear maps T: Vn → F can be described via tensor products of elements of V∗.

If, in addition to vector addition and scalar multiplication, there is a bilinear vector product V × V → V, the vector space is called an algebra; for instance, associative algebras are algebras with an associate vector product (like the algebra of square matrices, or the algebra of polynomials).

Functional analysis mixes the methods of linear algebra with those of mathematical analysis and studies various function spaces, such as Lp spaces.

Representation theory studies the actions of algebraic objects on vector spaces by representing these objects as matrices. It is interested in all the ways that this is possible, and it does so by finding subspaces invariant under all transformations of the algebra. The concept of eigenvalues and eigenvectors is especially important.

Algebraic geometry considers the solutions of systems of polynomial equations.

There are several related topics in the field of Computer Programming that utilizes much of the techniques and theorems Linear Algebra encompasses and refers to.

.

.

with equality only for v = 0.

with equality only for v = 0.

![f(x)=\frac{a_0}{2} + \sum_{n=1}^\infty \, [a_n \cos(nx) + b_n \sin(nx)].](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/a/3/5a38dd692be7e55a6bfb06bcf5a348a6.png)

![\langle f,h_k \rangle=\frac{a_0}{2}\langle h_0,h_k \rangle + \sum_{n=1}^\infty \, [a_n \langle h_n,h_k\rangle + b_n \langle\ g_n,h_k \rangle],](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/a/e/0/ae0113ab7a99b9cd7b364ee1763da0b3.png)

,

,

in terms of its coefficients

in terms of its coefficients  , where

, where  is not zero.

is not zero. the letter

the letter  is unknown, but the law of inverses can be used to discover its value:

is unknown, but the law of inverses can be used to discover its value:  . In

. In

and

and  are variables, and the letter

are variables, and the letter  is a

is a

), and the

), and the