From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

Social Security Administration, created in 1935, was the first major

federal welfare agency and continues to be the most prominent.

[1]

Social programs in the United States are

welfare subsidies

designed to meet needs of the American population. Federal and state

welfare programs include cash assistance, healthcare and medical

provisions, food assistance, housing subsidies, energy and utilities

subsidies, education and childcare assistance, and subsidies and

assistance for other basic services. Private provisions from employers,

either mandated by policy or voluntary, also provide similar social

welfare benefits.

The programs vary in eligibility requirements and are provided by

various organizations on a federal, state, local and private level.

They help to provide food, shelter, education, healthcare and money to

U.S. citizens through

primary and

secondary education,

subsidies of college education, unemployment disability insurance,

subsidies for eligible low-wage workers, subsidies for housing,

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits,

pensions for eligible persons and

health insurance programs that cover public employees. The

Social Security system

is sometimes considered to be a social aid program and has some

characteristics of such programs, but unlike these programs, social

security was designed as a self-funded security blanket—so that as the

payee pays in (during working years), they are pre-paying for the

payments they'll receive back out of the system when they are no longer

working.

Medicare is another prominent program, among other healthcare provisions such as

Medicaid and the

State Children's Health Insurance Program.

Congressional funding

Not including

Social Security and

Medicare,

Congress allocated almost $717 billion in federal funds in 2010 plus

$210 billion was allocated in state funds ($927 billion total) for means

tested welfare programs in the United States, of which half was for

medical care and roughly 40% for cash, food and housing assistance. Some

of these programs include funding for public schools, job training, SSI

benefits and medicaid.

[2] As of 2011, the public social spending-to-GDP ratio in the United States was below the

OECD average.

[3]

Roughly half of this welfare assistance, or $462 billion went to

families with children, most of which are headed by single parents.

[4]

Total Social Security and Medicare expenditures in 2013 were $1.3

trillion, 8.4% of the $16.3 trillion GNP (2013) and 37% of the total

Federal expenditure budget of $3.684 trillion.

[5][6]

In addition to government expenditures, private welfare spending,

i.e. social insurance programs provided to workers by employers,

[7] in the United States is estimated to be about 10% of the U.S. GDP or another $1.6 trillion, according to 2013 OECD estimates.

[8]

In 2001, Jacob Hacker estimated that public and private social welfare

expenditures constituted 21% and 13–14% of the United States'

GDP

respectively. In these estimates of private social welfare

expenditures, Hacker included mandatory private provisions (less than 1%

of GDP), subsidized and/or regulated private provisions (9–10% of GDP),

and purely private provisions (3–4% of GDP).

[9]

History

Public Health nursing made available through child welfare services, 1935.

Federal welfare programs

Colonial legislatures and later State governments adopted legislation patterned after the English

"poor" laws.

[10]

Aid to veterans, often free grants of land, and pensions for widows and

handicapped veterans, have been offered in all U.S. wars. Following

World War I, provisions were made for a full-scale system of hospital

and medical care benefits for veterans. By 1929, workers' compensation

laws were in effect in all but four states

[11].

These state laws made industry and businesses responsible for the costs

of compensating workers or their survivors when the worker was injured

or killed in connection with his or her job. Retirement programs for

mainly State and local government paid teachers, police officers, and

fire fighters—date back to the 19

th century. All these social programs were far from universal and varied considerably from one state to another.

Prior to the

Great Depression

the United States had social programs that mostly centered around

individual efforts, family efforts, church charities, business workers

compensation, life insurance and sick leave programs along with some

state tax supported social programs. The misery and poverty of the

great depression threatened to overwhelm all these programs. The severe

Depression of the 1930s made Federal action necessary

[12],

as neither the states and the local communities, businesses and

industries, nor private charities had the financial resources to cope

with the growing need among the American people

[13].

Beginning in 1932, the Federal Government first made loans, then

grants, to states to pay for direct relief and work relief. After that,

special Federal emergency relief like the

Civilian Conservation Corps and other public works programs were started.

[14] In 1935, President

Franklin D. Roosevelt's

administration proposed to Congress federal social relief programs and a

federally sponsored retirement program. Congress followed by the

passage of the 37 page Social Security Act, signed into law August 14,

1935 and "effective" by 1939—just as

World War II began. This program was expanded several times over the years.

Economic historians led by Price Fishback have examined the

impact of New Deal spending on improving health conditions in the 114

largest cities, 1929–1937. They estimated that every additional

$153,000 in relief spending (in 1935 dollars, or $2.2 million in 2016

dollars) was associated with a reduction of one infant death, one

suicide, and 2.4 deaths from infectious disease.

War on Poverty and Great Society programs (1960s)

Virtually all

food stamp costs are paid by the federal government.

[17] In 2008, 28.7 percent of the households headed by single women were considered poor.

[18]

Welfare reform (1990s)

Before the

Welfare Reform Act of 1996, welfare assistance was "once considered an open-ended right," but

welfare reform converted it "into a finite program built to provide short-term cash assistance and steer people quickly into jobs."

[19] Prior to reform, states were given "limitless"

[19] money by the federal government, increasing per family on welfare, under the 60-year-old

Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program.

[20]

This gave states no incentive to direct welfare funds to the neediest

recipients or to encourage individuals to go off welfare benefits (the

state lost federal money when someone left the system).

[21] Nationwide, one child in seven received AFDC funds,

[20] which mostly went to single mothers.

[17]

In 1996, under the

Bill Clinton administration,

Congress passed the

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act,

which gave more control of the welfare system to the states, with basic

requirements the states need to meet with regards to welfare services.

Still, most states offer basic assistance, such as health care, food

assistance, child care assistance, unemployment, cash aid, and housing

assistance. After reforms, which President Clinton said would "end

welfare as we know it,"

[17] amounts from the federal government were given out in a

flat rate per state based on

population.

[21]

Each state must meet certain criteria to ensure recipients are

being encouraged to work themselves out of welfare. The new program is

called

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

[20]

It encourages states to require some sort of employment search in

exchange for providing funds to individuals, and imposes a five-year

lifetime limit on cash assistance.

[17][20][22] The bill restricts welfare from most legal

immigrants and increased financial assistance for child care.

[22]

The federal government also maintains a contingency $2 billion TANF

fund (TANF CF) to assist states that may have rising unemployment.

[20]

The new TANF program expired on September 30, 2010, on schedule with

states drawing down the entire original emergency fund of $5 billion and

the contingency fund of $2 billion allocated by ARRA. Reauthorization

of TANF was not accomplished in 2011, but TANF block grants were

extended as part of the

Claims Resolution Act of 2010 (see

Temporary Aid for Needy Families for details).

Following these changes, millions of people left the welfare rolls (a 60% drop overall),

[22] employment rose, and the child poverty rate was reduced.

[17] A 2007

Congressional Budget Office study found that incomes in affected families rose by 35%.

[22] The reforms were "widely applauded"

[23] after "bitter protest."

[17] The Times called the reform "one of the few undisputed triumphs of American government in the past 20 years."

[24] However, more recent studies have found that the reforms increased deep poverty by 130–150%.

[25][26]

Critics of the reforms sometimes point out that the massive

decrease of people on the welfare rolls during the 1990s wasn't due to a

rise in actual gainful employment in this population, but rather, was

due almost exclusively to their offloading into

workfare,

giving them a different classification than classic welfare recipient.

The late 1990s were also considered an unusually strong economic time,

and critics voiced their concern about what would happen in an economic

downturn.

[17]

National Review editorialized that the

Economic Stimulus Act of 2009 will reverse the

welfare-to-work

provisions that Bill Clinton signed in the 1990s, and will again base

federal grants to states on the number of people signed up for welfare

rather than at a flat rate.

[21]

One of the experts who worked on the 1996 bill said that the provisions

would lead to the largest one-year increase in welfare spending in

American history.

[24] The

House bill provides $4 billion to pay 80% of states' welfare caseloads.

[20]

Although each state received $16.5 billion annually from the federal

government as welfare rolls dropped, they spent the rest of the

block grant on other types of assistance rather than saving it for worse economic times.

[19]

Spending on largest Welfare Programs

Federal Spending 2003–2013*[27]

|

|---|

|

Federal

Programs |

Spending

2003* |

Spending

2013*

|

| Medicaid Grants to States |

$201,389 |

$266,565

|

| Food Stamps (SNAP) |

61,717 |

82,603

|

| Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) |

40,027 |

55,123

|

| Supplemental Security Income (SSI) |

38,315 |

50,544

|

| Housing assistance |

37,205 |

49,739

|

| Child Nutrition Program (CHIP) |

13,558 |

20,842

|

| Support Payments to States, TANF |

28,980 |

20,842

|

| Feeding Programs (WIC & CSFP) |

5,695 |

6,671

|

| Low Income Home Energy Assistance |

2,542 |

3,704

|

Notes:

* Spending in millions of dollars

|

Timeline

The following is a short timeline of welfare in the United States:

[28]

1880s–1890s: Attempts were made to move poor people from work yards to

poor houses if they were in search of relief funds.

1893–1894: Attempts were made at the first unemployment payments, but were unsuccessful due to the 1893–1894

recession.

1932: The Great Depression had gotten worse and the first

attempts to fund relief failed. The "Emergency Relief Act", which gave

local governments $300 million, was passed into law.

1933: In March 1933,

President Franklin D. Roosevelt pushed Congress to establish the

Civilian Conservation Corps.

1935: The

Social Security Act was passed on June 17, 1935. The bill included direct relief (cash, food stamps, etc.) and changes for unemployment insurance.

1940: Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC) was established.

1964:

Johnson's War on Poverty is underway, and the

Economic Opportunity Act was passed. Commonly known as "the

Great Society"

1996: Passed under Clinton, the "

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996" becomes law.

2013:

Affordable Care Act goes into effect with large increases in Medicaid and subsidized medical insurance premiums go into effect.

Types

Means-tested

Spending in millions of dollars

2.3 Trillion Dollar Total of Social Security, Medicare and Means

Tested Welfare is low since latest 2013 means tested data not available

but 2013, the "real" TOTAL will be higher.

Social Security

The Social Security program mainly refers to the Old Age, Survivors,

and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program, and possibly the unemployment

insurance program.

Retirement Insurance Benefits

(RIB), also known as Old-age Insurance Benefits, are a form of social

insurance payments made by the U.S. Social Security Administration paid

based upon the attainment old age (62 or older).

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSD or SSDI) is a federal insurance program that provides

income supplements to people who are restricted in their ability to be

employed because of a notable

disability.

Unemployment insurance,

also known as unemployment compensation, provides for money, from the

United States and the state collected from employers, to workers who

have become unemployed through no fault of their own. The unemployment

benefits are run by each state with different state defined criteria for

duration, percent of income paid, etc.. Nearly all require the

recipient to document their search for employment to continue receiving

benefits. Extensions of time for receiving benefits are sometimes

offered for extensive work unemployment. These extra benefits are

usually in the form of loans from the federal government that have to be

repaid by each state.

General welfare

The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program provides stipends to

low-income people who are either aged (65 or older), blind, or disabled.

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) provides cash

assistance to indigent American families with dependent children.

Healthcare spending

Health care in the United States is provided by many separate legal

entities. Health care facilities are largely owned and operated by the

private sector.

Health insurance in the United States

is now primarily provided by the government in the public sector, with

60–65% of healthcare provision and spending coming from programs such as

Medicare,

Medicaid,

TRICARE, the

Children's Health Insurance Program, and the

Veterans Health Administration. Having some form of comprehensive health insurance is statutorily compulsory for most people lawfully residing within the US.

[30]

Medicare is a

social insurance program administered by the

United States government, providing

health insurance

coverage to people who are aged 65 and over; to those who are under 65

and are permanently physically disabled or who have a congenital

physical disability; or to those who meet other special criteria like

the

End Stage Renal Disease Program (ESRD). Medicare in the United States somewhat resembles a

single-payer health care system but is not.

[why?]

Before Medicare, only 51% of people aged 65 and older had health care

coverage, and nearly 30% lived below the federal poverty level.

Medicaid is a health program for certain people and families with low incomes and resources. It is a

means-tested program that is jointly funded by the state and federal governments, and is managed by the states.

[31] People served by Medicaid are

U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents, including low-income adults, their children, and people with certain

disabilities.

Medicaid is the largest source of funding for medical and

health-related services for people with limited income in the United

States.

The Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) is a program administered by the

United States Department of Health and Human Services that provides

matching funds to states for health insurance to families with children.

[32]

The program was designed to cover uninsured children in families with

incomes that are modest but too high to qualify for Medicaid.

The

Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Services Block Grant (or ADMS Block Grant) is a federal assistance

block grant given by the

United States Department of Health and Human Services.

The Trump administration has decided to cut $9 million in Affordable Care Act subsidies by 2018.

[33] This action was taken by use of Executive Order 13813, on October 12, 2017.

[34]

The initial goal had been for Republicans in Congress to use their

majority to "repeal and replace" the Affordable Care Act, but they

proved unable to do so

[35]; therefore, the Trump administration itself took measures to weaken the program.

[36] The healthcare changes are expected to be noticeable by the year 2019.

[37]

Education spending

Per capita spending on tertiary education is among the highest in the world.

Public education is managed by individual states, municipalities and

regional school districts. As in all developed countries,

primary and

secondary education is free, universal and mandatory. Parents do have the option of

home-schooling their children, though some states, such as

California (until a 2008 legal ruling overturned this requirement

[38]),

require parents to obtain teaching credentials before doing so.

Experimental programs give lower-income parents the option of using

government issued vouchers to send their kids to private rather than

public schools in some states/regions.

As of 2007, more than 80% of all primary and secondary students

were enrolled in public schools, including 75% of those from households

with

incomes in the

top 5%. Public schools commonly offer after-school programs and the government subsidizes private after school programs, such as the

Boys & Girls Club. While pre-school education is subsidized as well, through programs such as

Head Start,

many Americans still find themselves unable to take advantage of them.

Some education critics have therefore proposed creating a comprehensive

transfer system to make pre-school education universal, pointing out

that the financial returns alone would compensate for the cost.

Tertiary education is not free, but is subsidized by individual

states and the federal government. Some of the costs at public

institutions is carried by the state.

The government also provides grants, scholarships and subsidized

loans to most students. Those who do not qualify for any type of aid,

can obtain a government guaranteed loan and tuition can often be

deducted from the

federal income tax.

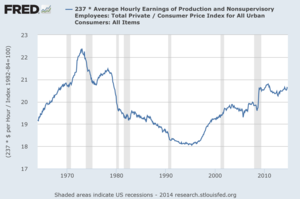

Despite subsidized attendance cost at public institutions and tax

deductions, however, tuition costs have risen at three times the rate of

median household income since 1982.

[39]

In fear that many future Americans might be excluded from tertiary

education, progressive Democrats have proposed increasing financial aid

and subsidizing an increased share of attendance costs. Some Democratic

politicians and political groups have also proposed to make public

tertiary education free of charge, i.e. subsidizing 100% of attendance

cost.

Food assistance

In the U.S., financial assistance for food purchasing for low- and

no-income people is provided through the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as the Food Stamp Program.

[40] This

federal aid program is administered by the

Food and Nutrition Service of the

U.S. Department of Agriculture,

but benefits are distributed by the individual U.S. states. It is

historically and commonly known as the Food Stamp Program, though all

legal references to "stamp" and "coupon" have been replaced by "EBT" and

"card," referring to the refillable, plastic

Electronic Benefit Transfer

(EBT) cards that replaced the paper "food stamp" coupons. To be

eligible for SNAP benefits, the recipients must have incomes below 130

percent of the poverty line, and also own few assets.

[41] Since the economic downturn began in 2008, the use of food stamps has increased.

[41]

The

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) is a

child nutrition program

for healthcare and nutrition of low-income pregnant women,

breastfeeding women, and infants and children under the age of five. The

eligibility requirement is a family income below 185% of the

U.S. Poverty Income Guidelines,

but if a person participates in other benefit programs, or has family

members who participate in SNAP, Medicaid, or Temporary Assistance for

Needy Families, they automatically meet the eligibility requirements.

The

Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) is a type of United States

federal assistance

provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to states in

order to provide a daily subsidized food service for an estimated 3.2

million children and 112,000 elderly or mentally or physically impaired

adults

[42] in non-residential, day-care settings.

[43]

Public housing

The

Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 created

Section 8 housing, the payment of rent assistance to private landlords on behalf of low-income households.

Impact

According to the Congressional Budget Office, social programs

significantly raise the standard of living for low-income Americans,

particularly the elderly. The poorest 20% of American households earn a

before-tax average of only $7,600, less than half of the federal

poverty line.

Social programs increase such households' before-tax income to $30,500.

Social Security and Medicare are responsible for two thirds of that

increase.

[44]

Political scientist

Benjamin Radcliff

has argued that more generous social programs produce a higher quality

of life for all citizens, rich and poor alike, as such programs not only

improve life for those directly receiving benefits (or living in fear

of someday needing them, from the prospect of unemployment or illness)

but also reduce the social pathologies (such as crime and anomie) that

are the result of poverty and insecurity. By creating a society with

less poverty and less insecurity, he argues, we move closer to creating a

nation of shared prosperity that works to the advantage of all. Thus,

his research suggests, life satisfaction (or "happiness") is strongly

related to the generosity of the social safety net (what economists

often call

decommodification), whether looking across the industrial democracies or across the American states.

[45]

Cato Institute says: The current welfare system provides such a high level of benefits that it acts as a disincentive for work.

[46]

Analysis

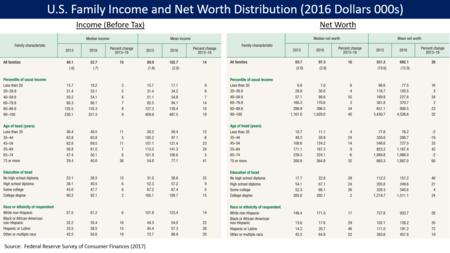

Household characteristics

| Characteristics of Households by Quintile 2010[47]

|

|---|

|

Household Income

Bracket (%) |

0–20 |

21–40 |

41–60 |

61–80 |

81–100

|

| Earners Per Household |

0.4 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

2.0

|

| Marital Status

|

| Married couples (%) |

17.0 |

35.9 |

48.8 |

64.3 |

78.4

|

| Single Parents or Single (%) |

83.0 |

64.1 |

51.2 |

35.7 |

21.6

|

| Ages of Householders

|

| Under 35 |

23.3 |

24 |

24.5 |

21.8 |

14.6

|

| 36–64 years |

43.6 |

46.6 |

55.4 |

64.3 |

74.7

|

| 65 years + |

33.1 |

29.4 |

20.1 |

13.9 |

10.7

|

| Work Status householders (%)

|

| Worked Full Time (%) |

17.4 |

44.7 |

61.1 |

71.5 |

77.2

|

| Worked Part Time (%) |

14.3 |

13.3 |

11.1 |

9.8 |

9.5

|

| Did Not Work (%) |

68.2 |

42.1 |

27.8 |

17.7 |

13.3

|

| Education of Householders (%)

|

| Less than High School |

26.7 |

16.6 |

8.8 |

5.4 |

2.2

|

| High School or some College |

61.2 |

65.4 |

62.9 |

58.5 |

37.6

|

| Bachelor's degree or Higher |

12.1 |

18.0 |

28.3 |

36.1 |

60.3

|

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau[unreliable source?]

|

Social programs have been implemented to promote a variety of

societal goals, including alleviating the effects of poverty on those

earning or receiving low income or encountering serious medical

problems, and ensuring retired people have a basic standard of living.

Unlike in Europe,

Christian democratic and

social democratic theories have not played a major role in shaping welfare policy in the United States.

[48] Entitlement programs in the U.S. were virtually non-existent until the administration of

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the implementation of the

New Deal programs in response to the

Great Depression. Between 1932 and 1981,

modern American liberalism dominated U.S. economic policy and the entitlements grew along with

American middle class wealth.

[49]

Eligibility for welfare benefits depends on a variety of factors, including gross and net income, family size, pregnancy,

homelessness, unemployment, and serious medical conditions like blindness, kidney failure or AIDS.

Drug testing for applicants

The United States adopted the

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act

in 1996, which gave individual states the authority to drug test

welfare recipients. Drug testing in order for potential recipients to

receive welfare has become an increasingly controversial topic.

Richard Hudson, a

Republican from

North Carolina

claims he pushes for drug screening as a matter of "moral obligation"

and that testing should be enforced as a way for the United States

government to discourage drug usage.

[50] Others claim that ordering the needy to drug test "stereotypes, stigmatizes, and criminalizes" them without need.

[51] States that currently require drug tests to be performed in order to receive public assistance include

Arizona,

Florida,

Georgia,

Missouri,

Oklahoma,

Tennessee, and

Utah.

[52]

Demographics of TANF recipients

A chart showing the overall decline of average monthly

TANF (formerly

AFDC) benefits per recipient 1962–2006 (in 2006 dollars).

[53]

Some have argued that welfare has come to be associated with poverty. Political scientist

Martin Gilens argues that

blacks

have overwhelmingly dominated images of poverty over the last few

decades and states that "white Americans with the most exaggerated

misunderstandings of the racial composition of the poor are the most

likely to oppose welfare".

[54] This perception possibly perpetuates negative

racial stereotypes and could increase Americans' opposition and racialization of welfare policies.

[54]

In FY 2010, African-American families comprised 31.9% of

TANF families,

white families comprised 31.8%, and 30.0% were

Hispanic.

[55]

Since the implementation of TANF, the percentage of Hispanic families

has increased, while the percentages of white and black families have

decreased. In FY 1997, African-American families represented 37.3% of

TANF recipient families, white families 34.5%, and Hispanic families

22.5%.

[56]

The population as a whole is composed of 63.7% whites, 16.3% Hispanic, 12.5% African-American, 4.8% Asian and 2.9% other races.

[57] TANF programs at a cost of about $20.0 billion (2013) have decreased in use as

Earned Income Tax Credits,

Medicaid grants,

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits,

Supplemental Security Income (SSI),

child nutrition programs,

Children's Health Insurance Program

(CHIP), housing assistance, Feeding Programs (WIC & CSFP), along

with about 70 more programs, have increased to over $700 billion more in

2013.

[58]

Costs

The

Great Recession made a large impact on welfare spending. In a 2011 article,

Forbes

reported, "The best estimate of the cost of the 185 federal means

tested welfare programs for 2010 for the federal government alone is

$717 billion, up a third since 2008, according to the

Heritage Foundation.

Counting state spending of about $210 billion, total welfare spending

for 2010 reached over $920 billion, up nearly one-fourth since 2008

(24.3%)"—and increasing fast.

[59] The previous decade had seen a 60% decrease in the number of people receiving welfare benefits,

[22] beginning with the passage of the

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act,

but spending did not decrease proportionally during that time period.

Combined annual federal and state spending is the equivalent of over

$21,000 for every person living below poverty level in America.