The Djabugay language group's mythical being, Damarri, transformed into a mountain range, is seen lying on his back above the Barron River Gorge, looking upwards to the skies, within north-east Australia's wet tropical forested landscape.

Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology (also known as Dreamtime or Dreaming stories, songlines, or Aboriginal oral literature) are the stories traditionally performed by Aboriginal peoples within each of the language groups across Australia.

All such myths variously "tell significant truths within each Aboriginal group's local landscape. They effectively layer the whole of the Australian continent's topography with cultural nuance and deeper meaning, and empower selected audiences with the accumulated wisdom and knowledge of Australian Aboriginal ancestors back to time immemorial".

David Horton's Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia contains an article on Aboriginal mythology observing:[3]

"A mythic map of Australia would show thousands of characters, varying in their importance, but all in some way connected with the land. Some emerged at their specific sites and stayed spiritually in that vicinity. Others came from somewhere else and went somewhere else."

"Many were shape changing, transformed from or into human beings or natural species, or into natural features such as rocks but all left something of their spiritual essence at the places noted in their stories."Australian Aboriginal mythologies have been characterized as "at one and the same time fragments of a catechism, a liturgical manual, a history of civilization, a geography textbook, and to a much smaller extent a manual of cosmography."[4]

Views on death

Death in Aboriginal religion in some aspects may seem like it has some Western traditions in regard to having a ceremony and mourning the loss of the person that is deceased. However, that is really the only thing that this religion has in common with Western religion as far as death is concerned. "For Aboriginal people when a person dies some form of the persons spirit and also their bones go back to the country they were born in".[5] "Aborigine people believe that they share their being with their country and all that is within it". "So when a person dies their country suffers, trees die and become scarred because it is believed that came into being because of the deceased person".[5]When an Aborigine person dies the families have death ceremonies called the "Sorry Business". "During this time the entire community and family mourns the loss of the person for days". "They are expected to cry together and share grief as a community". If someone was out of town and arrives after they have had a ceremony for the deceased, the entire community stops what they are doing and goes and tells them and mourns with them. "The family of the deceased all stay in one room and mourn for their loved one".[6]

"Naming a person after they have died is not allowed in the Aborigine religion". "To say someone's name after they die would be to disturb their spirit ".[6] Photos of the deceased are not allowed for fear of disturbing the spirit also. Many Aborigine families will not have any photographs of their loved ones after they die. "A smoking ceremony is also conducted when someone dies". "The community uses smoke on the belongings and also the residence of the deceased to help release the spirit". "Identifying the cause of death is determined by elders who hold the cultural authority to do so, and the causes in question are usually of a spiritual nature". "The ceremonies are likened to an autopsy of Western practice".

Ceremonies and mourning periods last days, weeks and even sometimes months depending upon the social status of the deceased person. It is culturally inappropriate for a non-Aboriginal person to contact and inform the next of kin of a person’s passing.[6] When someone passes away, the family of the deceased move out of their house and another family then moves in. Some families will move to "sorry camps" which are usually further away.[6] Mourning includes the recital of symbolic chants, the singing of songs, dance, body paint, and cuts on the bodies of the mourners. The body is placed on a raised platform for several months, covered in native plants. Sometimes a cave or a tree is used instead. "When nothing but bones are left, family and friends will scatter them in a variety of ways. They sometimes wrap the bones in a hand-knitted fabric and place them in a cave for eventual disintegration or place them in a naturally hollowed out log".[6]

The Aboriginals believe in a place called the "Land of the Dead". This place was also commonly known as the "sky-world", which is really just the sky. As long as certain rituals were carried out during their life and at the time of their death, the deceased is allowed to enter The Land of the Dead in the "Sky World". The spirit of the dead is also a part of different lands and sites and then those areas become sacred sites. This explains why the Aboriginals are very protective of sites they call sacred. The Aboriginals believe that life is a never-ending cycle. You are born, you die, you are born again as an animal, human or other life form .

The rituals that are performed enable the aborigine to return to the womb of all time which is another word for "Dream Time". It allows the spirit to be connected once more to all nature, to all their ancestors, and to their own personal meaning and place within the scheme of things. "The Dreamtime is a return to the real existence for the aborigine". "Life in time is simply a passing phase – a gap in eternity". It has a beginning and it has an end. "The experience of Dreamtime, whether through ritual or from dreams, flowed through into the life in time in practical ways". "The individual who enters the Dreamtime feels no separation between themselves and their ancestors". "The strengths and resources of the timeless enter into what is needed in the life of the present". "The future is less uncertain because the individual feels their life as a continuum linking past and future in unbroken connection". Through Dreamtime the limitations of time and space are overcome.[7] For the Aborigine people dead relatives are very much a part of continuing life. It is believed that in dreams dead relatives communicate their presence." At times they may bring healing if the dreamer is in pain". "Death is seen as part of a cycle of life in which one emerges from Dreamtime through birth, and eventually returns to the timeless, only to emerge again. It is also a common belief that a person leaves their body during sleep, and temporarily enters the Dreamtime".[7]

Antiquity

An Australian linguist, R. M. W. Dixon, recording Aboriginal myths in their original languages, encountered coincidences between some of the landscape details being told about within various myths, and scientific discoveries being made about the same landscapes.[8] In the case of the Atherton Tableland, myths tell of the origins of Lake Eacham, Lake Barrine, and Lake Euramo. Geological research dated the formative volcanic explosions described by Aboriginal myth tellers as having occurred more than 10,000 years ago. Pollen fossil sampling from the silt which had settled to the bottom of the craters confirmed the Aboriginal myth-tellers' story. When the craters were formed, eucalyptus forests dominated rather than the current wet tropical rain forests.[9][10] (See Lake Euramo for an excerpt of the original myth, translated.)Dixon observed from the evidence available that Aboriginal myths regarding the origin of the Crater Lakes might be dated as accurate back to 10,000 years ago.[9] Further investigation of the material by the Australian Heritage Commission led to the Crater Lakes myth being listed nationally on the Register of the National Estate,[11] and included within Australia's World Heritage nomination of the wet tropical forests, as an "unparalleled human record of events dating back to the Pleistocene era."[12]

Since then, Dixon has assembled a number of similar examples of Australian Aboriginal myths that accurately describe landscapes of an ancient past. He particularly noted the numerous myths telling of previous sea levels, including:[13]

- the Port Phillip myth (recorded as told to Robert Russell in 1850), describing Port Phillip Bay as once dry land, and the course of the Yarra River being once different, following what was then Carrum Carrum swamp.

- the Great Barrier Reef coastline myth (told to Dixon) in Yarrabah, just south of Cairns, telling of a past coastline (since flooded) which stood at the edge of the current Great Barrier Reef, and naming places now completely submerged after the forest types and trees that once grew there.

- the Lake Eyre myths (recorded by J. W. Gregory in 1906), telling of the deserts of Central Australia as once having been fertile, well-watered plains, and the deserts around present Lake Eyre having been one continuous garden. This oral story matches geologists' understanding that there was a wet phase to the early Holocene when the lake would have had permanent water.

Aboriginal mythology: whole of Australia

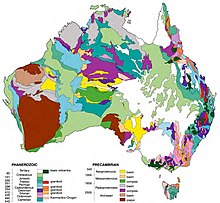

Map of the Aboriginal regions in Australia

Geological map of Australia

Diversity across a continent

There are 900 distinct Aboriginal groups across Australia,[16] each distinguished by unique names usually identifying particular languages, dialects, or distinctive speech mannerisms.[17] Each language was used for original myths, from which the distinctive words and names of individual myths derive.With so many distinct Aboriginal groups, languages, beliefs and practices, scholars cannot attempt to characterise, under a single heading, the full range and diversity of all myths being variously and continuously told, developed, elaborated, performed, and experienced by group members across the entire continent. (See external link[18] for one indicative spatial map of Australian Aboriginal groups, and see here for an earlier Tindale map of Aboriginal groups.)

The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia nevertheless observes: "One intriguing feature [of Aboriginal Australian mythology] is the mixture of diversity and similarity in myths across the entire continent."[3]

Public education about Aboriginal perspectives

The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation's booklet, Understanding Country, formally seeks to introduce non-indigenous Australians to Aboriginal perspectives on the environment. It makes the following generalisation about Aboriginal myths and mythology:[19]"...they generally describe the journeys of ancestral beings, often giant animals or people, over what began as a featureless domain. Mountains, rivers, waterholes, animal and plant species, and other natural and cultural resources came into being as a result of events which took place during these Dreamtime journeys. Their existence in present-day landscapes is seen by many indigenous peoples as confirmation of their creation beliefs..."

"The routes taken by the Creator Beings in their Dreamtime journeys across land and sea... link many sacred sites together in a web of Dreamtime tracks criss-crossing the country. Dreaming tracks can run for hundreds, even thousands of kilometres, from desert to the coast [and] may be shared by peoples in countries through which the tracks pass..."

An anthropological generalisation

Australian anthropologists willing to generalise suggest Aboriginal myths still being performed across Australia by Aboriginal peoples serve an important social function amongst their intended audiences: justifying the received ordering of their daily lives;[20] helping shape peoples' ideas; and assisting to influence others' behaviour.[21] In addition, such performance often continuously incorporates and "mythologises" historical events in the service of these social purposes in an otherwise rapidly changing modern world. As R.M. W. Dixon writes:[22]"It is always integral and common... that the Law (Aboriginal law) is something derived from ancestral peoples or Dreamings and is passed down the generations in a continuous line. While... entitlements of particular human beings may come and go, the underlying relationships between foundational Dreamings and certain landscapes are theoretically eternal ... the entitlements of people to places are usually regarded strongest when those people enjoy a relationship of identity with one or more Dreamings of that place. This is an identity of spirit, a consubstantiality, rather than a matter of mere belief...: the Dreaming pre-exists and persists, while its human incarnations are temporary."[23]

An Aboriginal generalization

Aboriginal specialists willing to generalise believe all Aboriginal myths across Australia, in combination, represent a kind of unwritten (oral) library within which Aboriginal peoples learn about the world and perceive a peculiarly Aboriginal 'reality' dictated by concepts and values vastly different from those of western societies:[24]"Aboriginal people learned from their stories that a society must not be human-centred but rather land centred, otherwise they forget their source and purpose ... humans are prone to exploitative behaviour if not constantly reminded they are interconnected with the rest of creation, that they as individuals are only temporal in time, and past and future generations must be included in their perception of their purpose in life."[25]

"People come and go but the Land, and stories about the Land, stay. This is a wisdom that takes lifetimes of listening, observing and experiencing ... There is a deep understanding of human nature and the environment... sites hold 'feelings' which cannot be described in physical terms... subtle feelings that resonate through the bodies of these people... It is only when talking and being with these people that these 'feelings' can truly be appreciated. This is... the intangible reality of these people..."[25]

Pan-Australian mythology

Rainbow Serpent

Australian carpet python, one of the forms the 'Rainbow Serpent' character may take in 'Rainbow Serpent' myths

In 1926 a British anthropologist specialising in Australian Aboriginal ethnology and ethnography, Professor Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, noted many Aboriginal groups widely distributed across the Australian continent all appeared to share variations of a single (common) myth telling of an unusually powerful, often creative, often dangerous snake or serpent of sometimes enormous size closely associated with the rainbows, rain, rivers, and deep waterholes.[26]

Radcliffe-Brown coined the term 'Rainbow Serpent' to describe what he identified to be a common, recurring myth. Working in the field in various places on the Australian continent, he noted the key character of this myth (the 'Rainbow Serpent') is variously named:[26]

- Kanmare (Boulia, Queensland); Tulloun: (Mount Isa, Queensland); Andrenjinyi (Pennefather River, Queensland), Takkan (Maryborough, Queensland); Targan (Brisbane, Queensland); Kurreah (Broken Hill, New South Wales);Wawi (Riverina, New South Wales), Neitee & Yeutta (Wilcannia, New South Wales), Myndie (Melbourne, Victoria); Bunyip (Western Victoria); Arkaroo (Flinders Ranges, South Australia); Wogal (Perth, Western Australia); Wanamangura (Laverton, Western Australia); Kajura (Carnarvon, Western Australia); Numereji (Kakadu, Northern Territory).

Even Australia's 'Bunyip' was identified as a 'Rainbow Serpent' myth of the above kind.[27] The term coined by Radcliffe-Brown is now commonly used and familiar to broader Australian and international audiences, as it is increasingly used by government agencies, museums, art galleries, Aboriginal organisations and the media to refer to the pan-Australian Aboriginal myth specifically, and as a shorthand allusion to Australian Aboriginal mythology generally.[28]

Captain Cook

Statue of Captain James Cook at Admiralty Arch, London

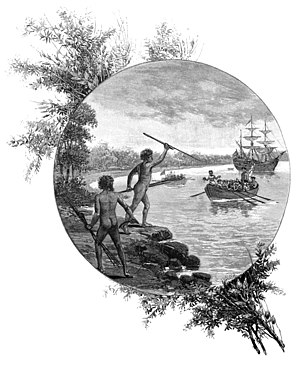

A number of linguists, anthropologists and others have formally documented another common Aboriginal myth occurring across Australia. Predecessors of the myth tellers encounter a mythical, exotic (most often English) character who arrives from the sea, bringing western colonialism, either offering gifts to the performer's predecessors or bringing great harm upon the performer's predecessors.[29]

This key mythical character is most often named 'Captain Cook', this being a 'mythical' character shared with the broader Australian community, who also attribute James Cook with playing a key role in colonising Australia.[30] The Aboriginal 'Captain Cook' is attributed with bringing British rule to Australia,[31] but his arrival is not celebrated. More often within the Aboriginal telling, he proves to be a villain.[30]

The many Aboriginal versions of this 'Captain Cook' are rarely oral recollections of encounters with the Lieutenant James Cook who first navigated and mapped Australia's east coast on the HM Bark Endeavour in 1770. Guugu Yimidhirr predecessors, along the Endeavour River, did encounter James Cook during a 7-week period beached at the site of the present town of Cooktown while the Endeavour was being repaired.[32] From this time the Guugu Yimidhirr did receive present-day names for places occurring in their local landscape; and the Guugu Yimmidhir may recollect this encounter.

The pan-Australian Captain Cook myth, however, tells of a generic, largely symbolic British character who arrives from across the oceans sometime after the Aboriginal world was formed and the original social order founded. This Captain Cook is a harbinger of dramatic transformations in the social order, bringing change and a different social order, into which present-day audiences have been born.[33] (see above regarding this social function played by Aboriginal myths)

In 1988 Australian anthropologist Kenneth Maddock assembled several versions of this 'Captain Cook' myth as recorded from a number of Aboriginal groups around Australia.[34] Included in his assemblage are:

- Batemans Bay, New South Wales: Percy Mumbulla told of Captain Cook's arriving on a large ship which anchored at Snapper Island, from which he disembarked to give the myth-teller's predecessors clothes (to wear) and hard biscuits (to eat). Then he returned to his ship and sailed away. Mumbulla told how his predecessors rejected Captain Cook's gifts, throwing them into the sea.[35]

- Cardwell, Queensland: Chloe Grant and Rosie Runaway told of how Captain Cook and his group seemed to stand up out of the sea with the white skin of ancestral spirits, returning to their descendants. Captain Cook arrived first offering a pipe and tobacco to smoke (which was dismissed as a 'burning thing... stuck in his mouth'), then boiling a billy of tea (which was dismissed as scalding 'dirty water'), next baking flour on the coals (which was rejected as smelling 'stale' and thrown away untasted), finally boiling beef (which smelled well, and tasted okay, once the salty skin was wiped off). Captain Cook and group then left, sailing away to the north, leaving Chloe Grant and Rosie Runaway's predecessors beating the ground with their fists, fearfully sorry to see the spirits of their ancestors depart in this way.[36]

- South-eastern side of the Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland: Rolly Gilbert told of how Captain Cook and others sailed the oceans in a boat, and decided to come to see Australia. There he encountered a couple of Rolly's predecessors whom he first intended to shoot, but instead tricked them into revealing the local population's main camping area, after which they:[37]

"set up the people [cattle industry] to go down the countryside and shoot people down, just like animal, they left them lying there for the hawks and crows... So a lot of old people and young people were struck by the head with the end of a gun and left there. They wanted to get the people wiped out because Europeans in Queensland had to run their stock: horses and cattle."

- Victoria River (Northern Territory): it is told in a Captain Cook saga that Captain Cook sailed from London to Sydney to acquire land. Admiring the country, he landed bullocks and men with firearms, following which local Aboriginal peoples in the Sydney area were massacred. Captain Cook made his way to Darwin, where he sent armed horsemen to hunt down the Aborigines in the Victoria River country, founding the city of Darwin and giving police plus cattle station managers orders on how to treat Aborigines.[38]

- Kimberley (Western Australia): Numerous Aboriginal myth-tellers say that Captain Cook is a European culture hero who landed in Australia. Using gunpowder, he set a precedent for the treatment of Aboriginal peoples throughout Australia, including the Kimberley. On returning to his home, he claimed he had not seen any Aboriginal peoples, and advised that the country was a vast and empty land which settlers could come and claim for themselves. In this myth, Captain Cook introduced 'Cook's Law', upon which the settlers rely. The Aboriginals note, however, that this is a recent, unjust and false law compared to Aboriginal law.[39]

Group-specific mythology

Murrinh-Patha people

|

Murrinh-Patha people's country[40]

|

In particular, scholars suggest the Murrinh-Patha have a oneness of thought, belief, and expression unequalled within Christianity, as they see all aspects of their lives, thoughts and culture as under the continuing influence of their Dreaming.[41] Within this Aboriginal religion, no distinction is drawn between things spiritual/ideal/mental and things material; nor is any distinction drawn between things sacred and things profane: rather all life is 'sacred', all conduct has 'moral' implication, and all life's meaning arises out of this eternal, everpresent Dreaming.[41]

"In fact, the isomorphic fit between the natural and supernatural means that all nature is coded and charged by the sacred, while the sacred is everywhere within the physical landscape. Myths and mythic tracks cross over.. thousands of miles, and every particular form and feature of the terrain has a well-developed 'story' behind it."[42]Animating and sustaining this Murrinh-patha mythology is an underlying philosophy of life that has been characterised by Stanner as a belief that life is "... a joyous thing with maggots at its centre.".[41] Life is good and benevolent, but throughout life's journey, there are numerous painful sufferings that each individual must come to understand and endure as he grows. This is the underlying message repeatedly being told within the Murrinh-patha myths. It is this philosophy that gives Murrinh-patha people motive and meaning in life.[41]

The following Murrinh-patha myth, for instance, is performed in Murrinh-patha ceremonies to initiate young men into adulthood.

"A woman, Mutjinga (the 'Old Woman'), was in charge of young children, but instead of watching out for them during their parents' absence, she swallowed them and tried to escape as a giant snake. The people followed her, spearing her and removing the undigested children from the body."[43]Within the myth and in its performance, young, unadorned children must first be swallowed by an ancestral being (who transforms into a giant snake), then regurgitated before being accepted as young adults with all the rights and privileges of young adults.[44]

Pintupi people

|

Pintupi people's country

|

"The Dreaming.. provides a moral authority lying outside the individual will and outside human creation.. although the Dreaming as an ordering of the cosmos is presumably a product of historical events, such an origin is denied."

"These human creations are objectified – thrust out – into principles or precedents for the immediate world.. Consequently, current action is not understood as the result of human alliances, creations, and choices, but is seen as imposed by an embracing, cosmic order."Within this Pintupi world view, three long geographical tracks of named places dominate, being interrelated strings of significant places named and created by mythic characters on their routes through the Pintupi desert region during the Dreaming. It is a complex mythology of narratives, songs and ceremonies known to the Pintupi as Tingarri. It is most completely told and performed by Pintupi peoples at larger gatherings within Pintupi country.