A democracy is a political system, or a system of decision-making within an institution or organization or a country, in which all members have an equal share of power. Modern democracies are characterized by two capabilities that differentiate them fundamentally from earlier forms of government: the capacity to intervene in their own societies and the recognition of their sovereignty by an international legalistic framework of similarly sovereign states. Democratic government is commonly juxtaposed with oligarchic and monarchic systems, which are ruled by a minority and a sole monarch respectively.

The oldest known existence of a democratic kingdom (Ganarajya) where king was chosen by people's votes can be traced way back in 599 BC at Vajji, Vaishali in ancient India. It was the birthplace of 24th and last Tirthankara in Jainism, named Mahavira. Democracy is generally associated with the efforts of the ancient Greeks and Romans, who were themselves considered the founders of Western civilization by the 18th century intellectuals who attempted to leverage these early democratic experiments into a new template for post-monarchical political organization. The extent to which these 18th century democratic revivalists succeeded in turning the democratic ideals of the ancient Greeks and Romans into the dominant political institution of the next 300 years is hardly debatable, even if the moral justifications they often employed might be. Nevertheless, the critical historical juncture catalyzed by the resurrection of democratic ideals and institutions fundamentally transformed the ensuing centuries and has dominated the international landscape since the dismantling of the final vestige of empire following the end of the Second World War.

Modern representative democracies attempt to bridge the gulf between the Hobbesian 'state of nature' and the grip of authoritarianism through 'social contracts' that enshrine the rights of the citizens, curtail the power of the state, and grant agency through the right to vote. While they engage populations with some level of decision-making , they are defined by the premise of distrust in the ability of human populations to make a direct judgement about candidates or decisions on issues.

Antiquity

Historic origins

Anthropologists have identified forms of proto-democracy that date back to small bands of hunter-gatherers that predate the establishment of agrarian, settled, societies and still exist virtually unchanged in isolated indigenous groups today. In these groups of generally 50-100 individuals, often tied closely by familial bonds, decisions are reached by consensus or majority and many times without the designation of any specific chief. Given that these dynamics are still alive and well today, it is plausible to assume that democracy in one form or another arises naturally in any well-bonded group or tribe.These types of democracy are commonly identified as tribalism, or primitive democracy. In this sense, a primitive democracy usually takes shape in small communities or villages when there are face-to-face discussions in a village council or with a leader who has the backing of village elders or other cooperative forms of government. This becomes more complex on a larger scale, such as when the village and city are examined more broadly as political communities. All other forms of rule – including monarchy, tyranny, aristocracy, and oligarchy – have flourished in more urban centers, often those with concentrated populations.

The concepts (and name) of democracy and constitution as a form of government originated in ancient Athens circa 508 B.C. In ancient Greece, where there were many city-states with different forms of government, democracy was contrasted with governance by elites (aristocracy), by one person (monarchy), by tyrants (tyranny), etc.

Proto-democratic societies

In recent decades scholars have explored the possibility that advancements toward democratic government occurred somewhere else (i.e. other than Greece) first, as Greece developed its complex social and political institutions long after the appearance of the earliest civilizations in Egypt and the Near East.Mesopotamia

The tablet containing the epic of Gilgamesh

Studying pre-Babylonian Mesopotamia, Thorkild Jacobsen used Sumerian epic, myth, and historical records to identify what he has called primitive democracy. By this, Jacobsen means a government in which ultimate power rests with the mass of free male citizens, although "the various functions of government are as yet little specialised [and] the power structure is loose". In early Sumer, kings like Gilgamesh did not hold the autocratic power that later Mesopotamian rulers wielded. Rather, major city-states functioned with councils of elders and "young men" (likely free men bearing arms) that possessed the final political authority, and had to be consulted on all major issues such as war.

The work has gained little outright acceptance. Scholars criticize the use of the word "democracy" in this context since the same evidence also can be interpreted convincingly to demonstrate a power struggle between primitive monarchy and noble classes, a struggle in which the common people function more like pawns rather than any kind of sovereign authority. Jacobsen conceded that the vagueness of the evidence prohibits the separation between the Mesopotamian democracy from a primitive oligarchy.

Indian subcontinent

Another claim for early democratic institutions comes from the independent "republics" of India, sanghas and ganas, which existed as early as the 6th century B.C. and persisted in some areas until the 4th century. The evidence for this is scattered, however, and no pure historical source exists for that period. In addition, Diodorus—a Greek historian who wrote two centuries after the time of Alexander the Great's invasion of India—mentions, without offering any detail, that independent and democratic states existed in India. Modern scholars note the word democracy at the time of the 3rd century B.C. and later suffered from degradation and could mean any autonomous state, no matter how oligarchic in nature.Key characteristics of the gana seem to include a monarch, usually known by the name raja, and a deliberative assembly. The assembly met regularly. It discussed all major state decisions. At least in some states, attendance was open to all free men. This body also had full financial, administrative, and judicial authority. Other officers, who rarely receive any mention, obeyed the decisions of the assembly. Elected by the gana, the monarch apparently always belonged to a family of the noble class of Kshatriya Varna. The monarch coordinated his activities with the assembly; in some states, he did so with a council of other nobles. The Licchavis had a primary governing body of 7,077 rajas, the heads of the most important families. On the other hand, the Shakyas, Koliyas, Mallas, and Licchavis, during the period around Gautama Buddha, had the assembly open to all men, rich and poor.

Scholars differ over how best to describe these governments, and the vague, sporadic quality of the evidence allows for wide disagreements. Some emphasize the central role of the assemblies and thus tout them as democracies; other scholars focus on the upper-class domination of the leadership and possible control of the assembly and see an oligarchy or an aristocracy. Despite the assembly's obvious power, it has not yet been established whether the composition and participation were truly popular. The first main obstacle is the lack of evidence describing the popular power of the assembly. This is reflected in the Arthashastra, an ancient handbook for monarchs on how to rule efficiently. It contains a chapter on how to deal with the sangas, which includes injunctions on manipulating the noble leaders, yet it does not mention how to influence the mass of the citizens—a surprising omission if democratic bodies, not the aristocratic families, actively controlled the republican governments. Another issue is the persistence of the four-tiered Varna class system. The duties and privileges on the members of each particular caste—rigid enough to prohibit someone sharing a meal with those of another order—might have affected the roles members were expected to play in the state, regardless of the formality of the institutions. A central tenet of democracy is the notion of shared decision-making power. The absence of any concrete notion of citizen equality across these caste system boundaries leads many scholars to claim that the true nature of ganas and sanghas is not comparable to truly democratic institutions.

Sparta

Bas-relief of Lycurgus, one of 23 great lawgivers depicted in the chamber of the United States House of Representatives

Ancient Greece, in its early period, was a loose collection of independent city states called poleis. Many of these poleis were oligarchies. The most prominent Greek oligarchy, and the state with which democratic Athens is most often and most fruitfully compared, was Sparta. Yet Sparta, in its rejection of private wealth as a primary social differentiator, was a peculiar kind of oligarchy and some scholars note its resemblance to democracy. In Spartan government, the political power was divided between four bodies: two Spartan Kings (diarchy), gerousia (Council of Gerontes (Elders), including the two kings), the ephors (representatives of the citizens who oversaw the Kings) and the apella (assembly of Spartans).

The two kings served as the head of the government. They ruled simultaneously, but they came from two separate lines. The dual kingship diluted the effective power of the executive office. The kings shared their judicial functions with other members of the gerousia. The members of the gerousia had to be over the age of 60 and were elected for life. In theory, any Spartan over that age could stand for election. However, in practice, they were selected from wealthy, aristocratic families. The gerousia possessed the crucial power of legislative initiative. Apella, the most democratic element, was the assembly where Spartans above the age of 30 elected the members of the gerousia and the ephors, and accepted or rejected gerousia's proposals. Finally, the five ephors were Spartans chosen in apella to oversee the actions of the kings and other public officials and, if necessary, depose them. They served for one year and could not be re-elected for a second term. Over the years, the ephors held great influence on the formation of foreign policy and acted as the main executive body of the state. Additionally, they had full responsibility for the Spartan educational system, which was essential for maintaining the high standards of the Spartan army. As Aristotle noted, ephors were the most important key institution of the state, but because often they were appointed from the whole social body it resulted in very poor men holding office, with the ensuing possibility that they could easily be bribed.

The creator of the Spartan system of rule was the legendary lawgiver Lycurgus. He is associated with the drastic reforms that were instituted in Sparta after the revolt of the helots in the second half of the 7th century BCE. In order to prevent another helot revolt, Lycurgus devised the highly militarized communal system that made Sparta unique among the city-states of Greece. All his reforms were directed towards the three Spartan virtues: equality (among citizens), military fitness, and austerity. It is also probable that Lycurgus delineated the powers of the two traditional organs of the Spartan government, the gerousia and the apella.

The reforms of Lycurgus were written as a list of rules/laws called Great Rhetra, making it the world's first written constitution. In the following centuries, Sparta became a military superpower, and its system of rule was admired throughout the Greek world for its political stability. In particular, the concept of equality played an important role in Spartan society. The Spartans referred to themselves as όμοιοι (Homoioi, men of equal status). It was also reflected in the Spartan public educational system, agoge, where all citizens irrespective of wealth or status had the same education. This was admired almost universally by contemporaries, from historians such as Herodotus and Xenophon to philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle. In addition, the Spartan women, unlike elsewhere, enjoyed "every kind of luxury and intemperance" including rights such as the right to inheritance, property ownership, and public education.

Overall, the Spartans were remarkably free to criticize their kings and they were able to depose and exile them. However, despite these democratic elements in the Spartan constitution, there are two cardinal criticisms, classifying Sparta as an oligarchy. First, individual freedom was restricted, since as Plutarch writes "no man was allowed to live as he wished", but as in a "military camp" all were engaged in the public service of their polis. And second, the gerousia effectively maintained the biggest share of power of the various governmental bodies.

The political stability of Sparta also meant that no significant changes in the constitution were made. The oligarchic elements of Sparta became even stronger, especially after the influx of gold and silver from the victories in the Persian Wars. In addition, Athens, after the Persian Wars, was becoming the hegemonic power in the Greek world and disagreements between Sparta and Athens over supremacy emerged. These led to a series of armed conflicts known as the Peloponnesian War, with Sparta prevailing in the end. However, the war exhausted both poleis and Sparta was in turn humbled by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE. It was all brought to an end a few years later, when Philip II of Macedon crushed what remained of the power of the factional city-states to his South.

Athens

The Acropolis of Athens by Leo von Klenze.

Athens is often regarded as the birthplace of democracy and remains an important reference-point for democracy.

Athens emerged in the 7th century BCE, like many other poleis, with a dominating powerful aristocracy. However, this domination led to exploitation, creating significant economic, political, and social problems. These problems exacerbated early in the 6th century; and, as "the many were enslaved to few, the people rose against the notables". At the same time, a number of popular revolutions disrupted traditional aristocracies. This included Sparta in the second half of the 7th century BCE. The constitutional reforms implemented by Lycurgus in Sparta introduced a hoplite state that showed, in turn, how inherited governments can be changed and lead to military victory. After a period of unrest between the rich and poor, Athenians of all classes turned to Solon to act as a mediator between rival factions, and reached a generally satisfactory solution to their problems.

Solon and the foundations of democracy

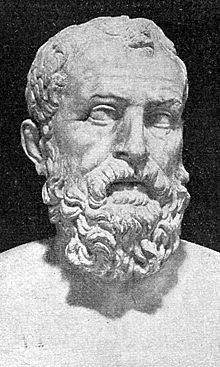

Bust of Solon from the National Museum, Naples

Solon(c. 638 – c. 558 BC), an Athenian (Greek) of noble descent but moderate means, was a lyric poet and later a lawmaker; Plutarch ranked him as one of the Seven Sages of the ancient world. Solon attempted to satisfy all sides by alleviating the suffering of the poor majority without removing all the privileges of the rich minority. Solon divided the Athenians into four property-classes, with different rights and duties for each. As the Rhetra did in Lycurgian Sparta, Solon formalized the composition and functions of the governmental bodies. All citizens gained the right to attend the Ecclesia (Assembly) and to vote. The Ecclesia became, in principle, the sovereign body, entitled to pass laws and decrees, elect officials, and hear appeals from the most important decisions of the courts. All but those in the poorest group might serve, a year at a time, on a new Boule of 400, which was to prepare the agenda for the Ecclesia. The higher governmental posts, those of the archons (magistrates), were reserved for citizens of the top two income groups. The retired archons became members of the Areopagus (Council of the Hill of Ares), which like the Gerousia in Sparta, was able to check improper actions of the newly powerful Ecclesia. Solon created a mixed timocratic and democratic system of institutions.

Overall, Solon devised the reforms of 594 BC to avert the political, economic, and moral decline in archaic Athens and gave Athens its first comprehensive code of law. The constitutional reforms eliminated enslavement of Athenians by Athenians, established rules for legal redress against over-reaching aristocratic archons, and assigned political privileges on the basis of productive wealth rather than of noble birth. Some of Solon's reforms failed in the short term, yet he is often credited with having laid the foundations for Athenian democracy.

Democracy under Cleisthenes and Pericles

The Pnyx with the speaker's platform, the meeting place of the people of Athens

Even though the Solonian reorganization of the constitution improved the economic position of the Athenian lower classes, it did not eliminate the bitter aristocratic contentions for control of the archonship, the chief executive post. Peisistratus became tyrant of Athens three times from 561 BCE and remained in power until his death in 527 BCE. His sons Hippias and Hipparchus succeeded him.

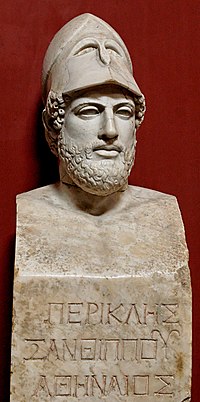

After the fall of tyranny (510 BCE) and before the year 508–507 was over, Cleisthenes proposed a complete reform of the system of government, which later was approved by the popular Ecclesia. Cleisthenes reorganized the population of citizens into ten tribes, with the aim to change the basis of political organization from the family loyalties to political ones, and improve the army's organization. He also introduced the principle of equality of rights for all male citizens, isonomia, by expanding access to power to more citizens. During this period, Athenians first used the word "democracy" (Greek: δημοκρατία – "rule by the people") to define their new system of government. In the next generation, Athens entered its Golden Age, becoming a great center of literature and art. Greek victories in Persian Wars (499–449 BCE) encouraged the poorest Athenians (who participated in the military campaigns) to demand a greater say in the running of their city. In the late 460s, Ephialtes and Pericles presided over a radicalization of power that shifted the balance decisively to the poorest sections of society, by passing laws which severely limited the powers of the Council of the Areopagus and allowed thetes (Athenians without wealth) to occupy public office. Pericles became distinguished as the Athenians' greatest democratic leader, even though he has been accused of running a political machine. In the following passage, Thucydides recorded Pericles, in the funeral oration, describing the Athenian system of rule:

| “ | Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition. The freedom which we enjoy in our government extends also to our ordinary life. | ” |

A bust of Pericles bearing the inscription "Pericles, son of Xanthippus, Athenian". Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from ca. 430 BCE.

The Athenian democracy of Cleisthenes and Pericles was based on freedom of citizens(through the reforms of Solon) and on equality of citizens(isonomia) - introduced by Cleisthenes and later expanded by Ephialtes and Pericles. To preserve these principles, the Athenians used lot for selecting officials. Casting lots aimed to ensure that all citizens were "equally" qualified for office, and to avoid any corruption allotment machines were used. Moreover, in most positions chosen by lot, Athenian citizens could not be selected more than once; this rotation in office meant that no-one could build up a power base through staying in a particular position.

The courts formed another important political institution in Athens; they were composed of a large number of juries with no judges, and they were selected by lot on a daily basis from an annual pool, also chosen by lot. The courts had unlimited power to control the other bodies of the government and its political leaders. Participation by the citizens selected was mandatory, and a modest financial compensation was given to citizens whose livelihood was affected by being "drafted" to office. The only officials chosen by elections, one from each tribe, were the strategoi (generals), where military knowledge was required, and the treasurers, who had to be wealthy, since any funds revealed to have been embezzled were recovered from a treasurer's private fortune. Debate was open to all present and decisions in all matters of policy were taken by majority vote in the Ecclesia (compare direct democracy), in which all male citizens could participate (in some cases with a quorum of 6000). The decisions taken in the Ecclesia were executed by the Boule of 500, which had already approved the agenda for the Ecclesia. The Athenian Boule was elected by lot every year and no citizen could serve more than twice.

Overall, the Athenian democracy was not only direct in the sense that decisions were made by the assembled people, but also directest in the sense that the people through the assembly, boule, and courts of law controlled the entire political process and a large proportion of citizens were involved constantly in the public business. And even though the rights of the individual (probably) were not secured by the Athenian constitution in the modern sense, the Athenians enjoyed their liberties not in opposition to the government, but by living in a city that was not subject to another power and by not being subjects themselves to the rule of another person.

The birth of political philosophy

Within the Athenian democratic environment, many philosophers from all over the Greek world gathered to develop their theories. Socrates (470-399 BCE) was the first to raise the question, further expanded by his pupil Plato (died 348/347), about the relation/position of an individual within a community. Aristotle (384–322 BCE) continued the work of his teacher, Plato, and laid the foundations of political philosophy. The political philosophy developed in Athens was, in the words of Peter Hall, "in a form so complete that hardly added anyone of moment to it for over a millennium". Aristotle systematically analyzed the different systems of rule that the numerous Greek city-states had and divided them into three categories based on how many ruled: the many (democracy/polity), the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), a single person (tyranny, or today: autocracy/monarchy). For Aristotle, the underlying principles of democracy are reflected in his work Politics:| “ | Now a fundamental principle of the democratic form of constitution is liberty—that is what is usually asserted, implying that only under this constitution do men participate in liberty, for they assert this as the aim of every democracy. But one factor of liberty is to govern and be governed in turn; for the popular principle of justice is to have equality according to number, not worth, and if this is the principle of justice prevailing, the multitude must of necessity be sovereign and the decision of the majority must be final and must constitute justice, for they say that each of the citizens ought to have an equal share; so that it results that in democracies the poor are more powerful than the rich, because there are more of them and whatever is decided by the majority is sovereign. This then is one mark of liberty which all democrats set down as a principle of the constitution. And one is for a man to live as he likes; for they say that this is the function of liberty, inasmuch as to live not as one likes is the life of a man that is a slave. This is the second principle of democracy, and from it has come the claim not to be governed, preferably not by anybody, or failing that, to govern and be governed in turns; and this is the way in which the second principle contributes to equalitarian liberty. | ” |

Decline, revival, and criticisms

The Athenian democracy, in its two centuries of life-time, twice voted against its democratic constitution (both times during the crisis at the end of the Pelopponesian War of 431 to 404 BC), establishing first the Four Hundred (in 411 BCE) and second Sparta's puppet régime of the Thirty Tyrants (in 404 BCE). Both votes took place under manipulation and pressure, but democracy was recovered in less than a year in both cases. Reforms following the restoration of democracy after the overthrow of the Thirty Tyrants removed most law-making authority from the Assembly and placed it in randomly selected law-making juries known as "nomothetai". Athens restored its democratic constitution again after King Phillip II of Macedon (reigned 359-336 BCE) and later Alexander the Great (reigned 336–323 BCE) unified Greece, but it was politically over-shadowed by the Hellenistic empires. Finally, after the Roman conquest of Greece in 146 BC, Athens was restricted to matters of local administration.However, democracy in Athens declined not only due to external powers, but due to its citizens, such as Plato and his student Aristotle. Because of their influential works, after the rediscovery of classics during the Renaissance, Sparta's political stability was praised, while the Periclean democracy was described as a system of rule where either the less well-born, the mob (as a collective tyrant), or the poorer classes held power. Only centuries afterwards, after the publication of A History of Greece by George Grote from 1846 onwards, did modern political thinkers start to view the Athenian democracy of Pericles positively. In the late 20th century scholars re-examined the Athenian system of rule as a model of empowering citizens and as a "post-modern" example for communities and organizations alike.

Rome

Even though Rome is classified as a Republic and not a democracy, its history has helped preserve the concept of democracy over the centuries. The Romans invented the concept of classics and many works from Ancient Greece were preserved. Additionally, the Roman model of governance inspired many political thinkers over the centuries, and today's modern (representative) democracies imitate more the Roman than the Greek models.The Roman Republic

The political structure as outlined in the Roman constitution resembled a mixed constitution and its constituent parts were comparable to those of the Spartan constitution: two consuls, embodying the monarchic form; the Senate, embodying the aristocratic form; and the people through the assemblies. The consul was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate. Consuls had power in both civil and military matters. While in the city of Rome, the consuls were the head of the Roman government and they would preside over the Senate and the assemblies. While abroad, each consul would command an army. The Senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consultum and were official advices to a magistrate. However, in practice, it was difficult for a magistrate to ignore the Senate's advice. The focus of the Roman Senate was directed towards foreign policy. Though it technically had no official role in the management of military conflict, the Senate ultimately was the force that oversaw such affairs. Also, it managed Rome's civil administration. The requirements for becoming a senator included having at least 100,000 denarii worth of land, being born of the patrician (noble aristocrats) class, and having held public office at least once before. New Senators had to be approved by the sitting members. The people of Rome through the assemblies had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation (or dissolution) of alliances. Despite the obvious power the assemblies had, in practice, the assemblies were the least powerful of the other bodies of government. An assembly was legal only if summoned by a magistrate and it was restricted from any legislative initiative or the ability to debate. And even the candidates for public office as Livy writes "levels were designed so that no one appeared to be excluded from an election and yet all of the clout resided with the leading men". Moreover, the unequal weight of votes was making a rare practice for asking the lowest classes for their votes.

Roman stability, in Polybius’ assessment, was owing to the checks each element put on the superiority of any other: a consul at war, for example, required the cooperation of the Senate and the people if he hoped to secure victory and glory, and could not be indifferent to their wishes. This was not to say that the balance was in every way even: Polybius observes that the superiority of the Roman to the Carthaginian constitution (another mixed constitution) at the time of the Hannibalic War was an effect of the latter’s greater inclination toward democracy than to aristocracy. Moreover, recent attempts to posit for Rome personal freedom in the Greek sense – eleutheria: living as you like – have fallen on stony ground, since eleutheria (which was an ideology and way of life in the democratic Athens) was anathema in the Roman eyes. Rome’s core values included order, hierarchy, discipline, and obedience. These values were enforced with laws regulating the private life of an individual. The laws were applied in particular to the upper classes, since the upper classes were the source of Roman moral examples.

Rome became the ruler of a great Mediterranean empire. The new provinces brought wealth to Italy, and fortunes were made through mineral concessions and enormous slave run estates. Slaves were imported to Italy and wealthy landowners soon began to buy up and displace the original peasant farmers. By the late 2nd century this led to renewed conflict between the rich and poor and demands from the latter for reform of the constitution. The background of social unease and the inability of the traditional republican constitutions to adapt to the needs of the growing empire led to the rise of a series of over-mighty generals, championing the cause of either the rich or the poor, in the last century BCE.

Transition to empire

Over the next few hundred years, various generals would bypass or overthrow the Senate for various reasons, mostly to address perceived injustices, either against themselves or against poorer citizens or soldiers. One of those generals was Julius Caesar, where he marched on Rome and took supreme power over the republic. Caesar's career was cut short by his assassination at Rome in 44 BCE by a group of Senators including Marcus Junius Brutus. In the power vacuum that followed Caesar's assassination, his friend and chief lieutenant, Marcus Antonius, and Caesar's grandnephew Octavian who also was the adopted son of Caesar, rose to prominence. Their combined strength gave the triumvirs absolute power. However, in 31 BC war between the two broke out. The final confrontation occurred on 2 September 31 BCE, at the naval Battle of Actium where the fleet of Octavian under the command of Agrippa routed Antony's fleet. Thereafter, there was no one left in the Roman Republic who wanted to, or could stand against Octavian, and the adopted son of Caesar moved to take absolute control. Octavian left the majority of Republican institutions intact, though he influenced everything using personal authority and ultimately controlled the final decisions, having the military might to back up his rule if necessary. By 27 BCE the transition, though subtle, disguised, and relying on personal power over the power of offices, was complete. In that year, Octavian offered back all his powers to the Senate, and in a carefully staged way, the Senate refused and titled Octavian Augustus — "the revered one". He was always careful to avoid the title of rex — "king", and instead took on the titles of princeps — "first citizen" and imperator, a title given by Roman troops to their victorious commanders.

The Roman Empire and late antiquities

The Roman Empire had been born. Once Octavian named Tiberius as his heir, it was clear to everyone that even the hope of a restored Republic was dead. Most likely, by the time Augustus died, no one was old enough to know a time before an Emperor ruled Rome. The Roman Republic had been changed into a despotic régime, which, underneath a competent and strong Emperor, could achieve military supremacy, economic prosperity, and a genuine peace, but under a weak or incompetent one saw its glory tarnished by cruelty, military defeats, revolts, and civil war.The Roman Empire was eventually divided between the Western Roman Empire which fell in 476 AD and the Eastern Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire) which lasted until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD.

- The Germanic tribal thing assemblies described by Tacitus in his Germania.

- The Christian Church well into the 6th century AD had its bishops elected by popular acclaim.

- The collegia of the Roman period: associations of various social, economic, religious, funerary and even sportive natures elected officers yearly, often directly modeled on the Senate of Rome.

Institutions in the medieval era

Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker is teaching the Swedish king Olof Skötkonung that the power resides with the people, 1018, Uppsala, by C. Krogh.

Most of the procedures used by modern democracies are very old. Almost all cultures have at some time had their new leaders approved, or at least accepted, by the people; and have changed the laws only after consultation with the assembly of the people or their leaders. Such institutions existed since before the times of the Iliad or of the Odyssey, and modern democracies are often derived from or inspired by them, or what remained of them.

Nevertheless, the direct result of these institutions was not always a democracy. It was often a narrow oligarchy, as in Venice, or even an absolute monarchy, as in Florence, in the Renaissance period; but during the medieval period guild democracies did evolve.

Early institutions included:

- The continuations of the early Germanic thing:

- The Witenagemot (folkmoot) of Early Medieval England, councils of advisors to the kings of the petty kingdoms and then that of a unified England before the Norman Conquest.

- The Frankish custom of the Märzfeld or Camp of Mars.[78]

- In the Iberian Peninsula, in Portuguese, Leonese, Castillian, Aragonese, Catalan and Valencian customs, cortes were periodically convened to debate the state of the Realms.

- Tynwald, on the Isle of Man, claims to be one of the oldest continuous parliaments in the world, with roots back to the late 9th or 10th century.

- The Althing, the parliament of the Icelandic Commonwealth, founded in 930. It consisted of the 39, later 55, goðar; each owner of a goðarð; and each hereditary goði kept a tight hold on his membership, which could in principle be lent or sold. Thus, for example, when Burnt Njal's stepson wanted to enter it, Njal had to persuade the Althing to enlarge itself so a seat would become available. But as each independent farmer in the country could choose what goði represented him, the system could be claimed as an early form of democracy. The Alþing has run nearly continuously to the present day. The Althing was preceded by less elaborate "things" (assemblies) all over Northern Europe.

- The Thing of all Swedes, which took place annually at Uppsala at the end of February or in early March. As in Iceland, the lawspeaker presided over the assemblies, but the Swedish king functioned as a judge. A famous incident took place circa 1018, when King Olof Skötkonung wanted to pursue the war against Norway against the will of the people. Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker reminded the king in a long speech that the power resided with the Swedish people and not with the king. When the king heard the din of swords beating the shields in support of Þorgnýr's speech, he gave in. Adam of Bremen wrote that the people used to obey the king only when they thought his suggestions seemed better, although in war his power was absolute.

- The Swiss Landsgemeinde.

- The election of Uthman in the Rashidun Caliphate (7th century).

- The election of Gopala in the Pala Empire (8th century).

- The túatha system in early medieval Ireland. Landowners and the masters of a profession or craft were members of a local assembly, known as a túath. Each túath met in annual assembly which approved all common policies, declared war or peace on other tuatha, and accepted the election of a new "king"; normally during the old king's lifetime, as a tanist. The new king had to be descended within four generations from a previous king, so this usually became, in practice, a hereditary kingship; although some kingships alternated between lines of cousins. About 80 to 100 túatha coexisted at any time throughout Ireland. Each túath controlled a more or less compact area of land which it could pretty much defend from cattle-raids, and this was divided among its members.

- The Ibadites of Oman, a minority sect distinct from both Sunni and Shia Muslims, have traditionally chosen their leaders via community-wide elections of qualified candidates starting in the 8th century. They were distinguished early on in the region by their belief that the ruler needed the consent of the ruled. The leader exercised both religious and secular rule.

- The Papal election, 1061,

- The guilds, of economic, social and religious natures, in the later Middle Ages elected officers for yearly terms.

- The city-states (republics) of medieval Italy, as Venice and Florence, and similar city-states in Switzerland, Flanders and the Hanseatic league had not a modern democratic system but a guild democratic system. The Italian cities in the middle medieval period had "lobbies war" democracies without institutional guarantee systems (a full developed balance of powers). During late medieval and renaissance periods, Venice became an oligarchy and others became "Signorie". They were, in any case in late medieval times, not nearly as democratic as the Athenian-influenced city-states of Ancient Greece (discussed above), but they served as focal points for early modern democracy.

- Veche, Wiec – popular assemblies in Slavic countries. In Poland wiece have developed in 1182 into the Sejm – the Polish parliament. The veche was the highest legislature and judicial authority in the republics of Novgorod until 1478 and Pskov until 1510.

- The elizate system of the Basque Country in which farmholders of a rural area connected to a particular church would meet to reach decisions on issues affecting the community and to elect representatives to the provincial Batzar Nagusiak/Juntos Generales.

- The rise of democratic parliaments in England and Scotland: Magna Carta (1215) limiting the authority of powerholders; first representative parliament (1265). The Magna Carta implicitly supported what became the English writ of habeas corpus, safeguarding individual freedom against unlawful imprisonment with right to appeal. The emergence of petitioning in the 13th century is some of the earliest evidence of this parliament being used as a forum to address the general grievances of ordinary people.

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

Historian Jack Weatherford has argued that the ideas leading to the United States Constitution and democracy derived from various indigenous peoples of the Americas including the Iroquois. Weatherford claimed this democracy was founded between the years 1000–1450, and lasted several hundred years, and that the U.S. democratic system was continually changed and improved by the influence of Native Americans throughout North America.Temple University professor of anthropology and an authority on the culture and history of the Northern Iroquois Elizabeth Tooker has reviewed these claims and concluded they are myth rather than fact. The idea that North American Indians had a democratic culture is several decades old, but not usually expressed within historical literature. The relationship between the Iroquois League and the Constitution is based on a portion of a letter written by Benjamin Franklin and a speech by the Iroquois chief Canasatego in 1744. Tooker concluded that the documents only indicate that some groups of Iroquois and white settlers realized the advantages of a confederation, and that ultimately there is little evidence to support the idea that eighteenth century colonists were knowledgeable regarding the Iroquois system of governance.

What little evidence there is regarding this system indicates chiefs of different tribes were permitted representation in the Iroquois League council, and this ability to represent the tribe was hereditary. The council itself did not practice representative government, and there were no elections; deceased chiefs' successors were selected by the most senior woman within the hereditary lineage in consultation with other women in the clan. Decision making occurred through lengthy discussion and decisions were unanimous, with topics discussed being introduced by a single tribe. Tooker concludes that "...there is virtually no evidence that the framers borrowed from the Iroquois" and that the myth is largely based on a claim made by Iroquois linguist and ethnographer J.N.B. Hewitt which was exaggerated and misinterpreted after his death in 1937.

The Aztecs also practiced elections, but the elected officials elected a supreme speaker, not a ruler.

Rise of democracy in modern national governments

Early Modern Era milestones

The election of Augustus II at Wola, outside Warsaw, Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in 1697. Painted by Bernardo Bellotto.

- Norman Davies notes that Golden Liberty, the Nobles' Democracy (Rzeczpospolita Szlachecka) arose in the Kingdom of Poland and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This foreshadowed a democracy of about ten percent of the population of the Commonwealth, consisting of the nobility, who were an electorate for the office of the King. They observed Nihil novi of 1505, Pacta conventa and King Henry's Articles (1573). See also: Szlachta history and political privileges, Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Organisation and politics of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

- The Case of Proclamations (1610) in England decided that "the King by his proclamation or other ways cannot change any part of the common law, or statute law, or the customs of the realm" and that "the King hath no prerogative, but that which the law of the land allows him."

- Dr. Bonham's Case (1610), decided that "in many cases, the common law will control Acts of Parliament".

- The Virginia House of Burgesses, established in 1619, is the first representative legislative body in the New World.

- The Mayflower Compact, signed in 1620, an agreement between the Pilgrims, on forming a government between themselves, based on majority rule.

- During a period of renewed interest in Magna Carta, the Petition of Right (1628) was passed by the Parliament of England. It established, among other things, the illegality of taxation without parliamentary consent and of arbitrary imprisonment.

- The idea of the political party with factions took form in Britain around the time of the English Civil War (1642–1651). Soldiers from the Parliamentarian New Model Army and a faction of Levellers freely debated rights to political representation during the Putney Debates of 1647. The Levellers published a newspaper (The Moderate) and pioneered political petitions, pamphleteering and party colours. Later, the pre-war Royalist (then Cavalier) and opposing Parliamentarian groupings became the Tory party and the Whigs in the Parliament.

- English Act of Habeas Corpus (1679), safeguarding individual freedom against unlawful imprisonment with right to appeal; one of the documents integral to the constitution of the United Kingdom and the history of the parliament of the United Kingdom.

- William Penn wrote his Frame of Government of Pennsylvania in 1682. The document gave the colony a representative legislature and granted liberal freedoms to the colony's citizens.

- A bill of rights is enacted by the Parliament of England in 1689. The Bill of Rights 1689 set out the requirement for regular parliaments, free elections, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament, and limited the power of the monarch. It ensured (with the Glorious Revolution of 1688) that, unlike much of the rest of Europe, royal absolutism would not prevail.

Eighteenth and nineteenth century milestones

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen approved by the National Assembly of France, 26 August 1789.

- 1707: The first Parliament of Great Britain is established after the merger of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland under the Acts of Union 1707. From around 1721–42, Robert Walpole, regarded as the first prime minister of Great Britain, chaired cabinet meetings, appointed all other ministers, and developed the doctrine of cabinet solidarity.

- 1755: The Corsican Republic led by Pasquale Paoli with the Corsican Constitution

- From the late 1770s: new Constitutions and Bills explicitly describing and limiting the authority of powerholders, many based on the English Bill of Rights (1689). Historian Norman Davies calls the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Constitution of May 3, 1791 "the first constitution of its kind in Europe".

- The United States: the Founding Fathers

rejected 'democracy' as defined by the Greeks, preferring instead 'a

natural aristocracy', whereby only the landed gentry were entitled to a

place in Congress.

The Americans, as with the British, took their cue from the Roman

republic model: only the patrician classes were involved in government.

- 1776: Virginia Declaration of Rights

- United States Constitution ratified in 1788, created bicameral legislature with members of the House of Representatives elected "by the People of the several states," and members of the Senate elected by the state legislatures. The Constitution did not originally define who was eligible to vote, leaving that to the constituent states, which mostly enfranchised only adult white males who owned land.

- 1791: the United States Bill of Rights ratified.

- 1790s: First Party System in U.S. involves invention of locally rooted political parties in the United States; networks of party newspapers; new canvassing techniques; use of caucus to select candidates; fixed party names; party loyalty; party platform (Jefferson 1799);

- 1800: peaceful transition between parties

- 1780s: development of social movements identifying themselves with the term 'democracy': Political clashes between 'aristocrats' and 'democrats' in Benelux countries changed the semi-negative meaning of the word 'democracy' in Europe, which was until then regarded as synonymous with anarchy, into a much more positive opposite of 'aristocracy'.

- 1789–1799: the French Revolution

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen adopted on 26 August 1789 which declared that "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights" and proclaimed the universal character of human rights.

- Universal male suffrage established for the election of the National Convention in September 1792, but revoked by the Directory in 1795.

- Slavery abolished in the French colonies by the National Convention on 4 February 1794, with Black people made equal to White people ("All men, without distinction of color, residing in the colonies are French citizens and will enjoy all the rights assured by the Constitution"). Slavery was re-established by Napoleon in 1802.

The establishment of universal male suffrage in France in 1848 was an important milestone in the history of democracy.

- 1791: The Haitian Revolution a successful slave revolution, established a free republic.

- The United Kingdom

- 1807: The Slave Trade Act banned the trade across the British Empire after which the U.K. established the Blockade of Africa and enacted international treaties to combat foreign slave traders.

- 1832: The passing of the Reform Act, which gave representation to previously under represented urban areas in the U.K. and extended the voting franchise to a wider population.

- 1833: The Slavery Abolition Act was passed, which took effect across the British Empire from 1 August 1834.

- 1820: First Cortes Gerais in Portugal under a Constitutional Charter.

- 1835: Serbia's first modern constitution

- 1848: Universal male suffrage was re-established in France in March of that year, in the wake of the French Revolution of 1848.

- 1848: Following the French, the Revolutions of 1848, although in many instances forcefully put down, did result in democratic constitutions in some other European countries, among them Denmark and Netherlands.

- 1850s: introduction of the secret ballot in Australia; 1872 in UK; 1892 in USA

- 1853: Black Africans given the vote for the first time in Southern Africa, in the British-administered Cape Province.

- 1856: USA – property ownership requirements were eliminated in all states, giving suffrage to most adult white males. However, tax-paying requirements remained in five states until 1860 and in two states until the 20th century.

- 1870: USA – 15th Amendment to the Constitution, prohibits voting rights discrimination on the basis of race, colour, or previous condition of slavery.

- 1878-80: William Ewart Gladstone's UK Midlothian campaign ushered in the modern political campaign.

- 1893: New Zealand is the first nation to introduce universal suffrage by awarding the vote to women (universal male suffrage had been in place since 1879).

- 1905: Persian Constitutional Revolution, first parliamentary system in middle east.

The secret ballot

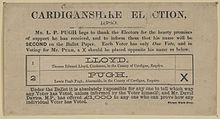

A British secret ballot paper, 1880

The notion of a secret ballot, where one is entitled to the privacy of their votes, is taken for granted by most today by virtue of the fact that it is simply considered the norm. However, this practice was highly controversial in the 19th century; it was widely argued that no man would want to keep his vote secret unless he was ashamed of it.

The two earliest systems used were the Victorian method and the South Australian method. Both were introduced in 1856 to voters in Victoria and South Australia. The Victorian method involved voters crossing out all the candidates whom he did not approve of. The South Australian method, which is more similar to what most democracies use today, had voters put a mark in the preferred candidate's corresponding box. The Victorian voting system also was not completely secret, as it was traceable by a special number.

The stone inscriptions in a temple say that ballot elections were held in South India by a method called Kudavolai system. Kudavolai means the ballot sheet of leaf that was put secretly in a pot vessel called "kudam". The details are found inscribed on the walls of the village assembly hall. Actually, the once village-assembly hall is the present temple. The details show that the village had a secret ballot electoral system and a written Constitution, prescribing the mode of elections.

Waves of democracy in the 20th century

The three 20th century waves of democracy, based on the number of nations 1800–2003 scoring 8 or higher on Polity IV scale, another widely used measure of democracy.

The end of the First World War was a temporary victory for democracy in Europe, as it was preserved in France and temporarily extended to Germany. Already in 1906 full modern democratic rights, universal suffrage for all citizens was implemented constitutionally in Finland as well as a proportional representation, open list system. Likewise, the February Revolution in Russia in 1917 inaugurated a few months of liberal democracy under Alexander Kerensky until Lenin took over in October. The terrible economic impact of the Great Depression hurt democratic forces in many countries. The 1930s became a decade of dictators in Europe and Latin America.

In 1918 the United Kingdom granted the right to vote to women over 30 who met a property qualification the right to vote, a second one was later passed in 1928 granting women and men equal rights. On August 18, 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment (Amendment XIX) to the United States Constitution was adopted which prohibits the states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex. French women got the right to vote in 1944, but did not actually cast their ballot for the first time until April 29, 1945.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted full U.S. citizenship to America's indigenous peoples, called "Indians" in this Act. (The Fourteenth Amendment guarantees citizenship to persons born in the U.S., but only if "subject to the jurisdiction thereof"; this latter clause excludes certain indigenous peoples.) The act was signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge on 2 June 1924. The act further enfranchised the rights of peoples resident within the boundaries of the United States.

Post-World War II

World War II was ultimately a victory for democracy in Western Europe, where representative governments were established that reflected the general will of their citizens. However, many countries of Central and Eastern Europe became undemocratic Soviet satellite states. In Southern Europe, a number of right-wing authoritarian dictatorships (most notably in Spain and Portugal) continued to exist.- MaxRange data has defined and categorised the level of democracy and political regime type to all states and months from 1789 to this day and updating. MaxRange shows a dramatic expansion of democracy, especially from 1989. The third wave of democracy has been successful and covered major parts of previous autocratic areas. MaxRange can show detailed correlations between success of democracy and many relevant variables, such as previous democratic history, the transitional phase and selection of institutional political system. Even though the number of democratic states has continued to grow since 2006, the share of weaker electoral democracies has grown significantly. This is the strongest causal factor behind fragile democracies.

Decolonisation and civil rights movements

World War II also planted seeds of democracy outside Europe and Japan, as it weakened, with the exception of the USSR and the United States, all the old colonial powers while strengthening anticolonial sentiment worldwide. Many restive colonies/possessions were promised subsequent independence in exchange for their support for embattled colonial powers during the war.The aftermath of World War II also resulted in the United Nations' decision to partition the British Mandate into two states, one Jewish and one Arab. On 14 May 1948 the state of Israel declared independence and thus was born the first full democracy in the Middle East. Israel is a representative democracy with a parliamentary system and universal suffrage.

India became a Democratic Republic in 1950 after achieving independence from Great Britain in 1947. After holding its first national elections in 1952, India achieved the status of the world's largest liberal democracy with universal suffrage which it continues to hold today. Most of the former British and French colonies were independent by 1965 and at least initially democratic; those that were formerly part of the British Empire often adopted the Westminster parliamentary system. The process of decolonisation created much political upheaval in Africa and parts of Asia, with some countries experiencing often rapid changes to and from democratic and other forms of government.

In the United States of America, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act enforced the 15th Amendment. The 24th Amendment ended poll taxing by removing all tax placed upon voting, which was a technique commonly used to restrict the African American vote. The Voting Rights Act also granted voting rights to all Native Americans, irrespective of their home state. The minimum voting age was reduced to 18 by the 26th Amendment in 1971.

Late Cold War and after

New waves of democracy swept across Southern Europe in the 1970s, as a number of right-wing nationalist dictatorships fell from power. Later, in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, the communist states in the USSR sphere of influence were also replaced with liberal democracies.Much of Eastern Europe, Latin America, East and Southeast Asia, and several Arab, central Asian and African states, and the not-yet-state that is the Palestinian Authority moved towards greater liberal democracy in the 1990s and 2000s.

Countries highlighted in blue are designated "electoral democracies" in Freedom House's 2017 survey "Freedom in the World", covering the year 2016.

Democracy in the 21st century

In the 21st century, democracy movements have been seen across the world. In the Arab world, an unprecedented series of major protests occurred with citizens of Egypt, Tunisia, Bahrain, Yemen, Jordan, Syria and other countries across the MENA region demanding democratic rights. This revolutionary wave was given the term Tunisia Effect, as well as the Arab Spring. The Palestinian Authority also took action to address democratic rights.In Iran, following a highly disputed presidential vote fraught with corruption, Iranian citizens held a major series of protests calling for change and democratic rights (see: the 2009–2010 Iranian election protests and the 2011 Iranian protests). The 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq led to a toppling of Saddam Hussein and a new constitution with free and open elections.

In Asia, the country of Burma (also known as Myanmar) had long been ruled by a military junta; however, in 2011, the government changed to allow certain voting rights and released democracy-leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest. However, Burma still will not allow Suu Kyi to run for election and still has major human rights problems and not full democratic rights. However, this was later partially abrogated with the election of Suu Kyi's national league for democracy party and her appointment as the de facto leader of Burma (Myanmar) with the title "state councellor", as she is still not allowed to be president and therefore leads through a figurehead, Htin Kyaw. Human rights, however, have not improved. In Bhutan, in December 2005, the 4th King Jigme Singye Wangchuck announced that the first general elections would be held in 2008, and that he would abdicate the throne in favor of his eldest son. Bhutan is currently undergoing further changes to allow for a constitutional monarchy. In the Maldives, protests and political pressure led to a government reform which allowed democratic rights and presidential elections in 2008. These were however undone by a coup in 2018.

Not all movement has been pro-democratic however. In Poland and Hungary, so-called 'illiberal democracies' have taken hold, with the ruling parties in both countries considered by the EU and civil society to be working to undermine democratic governance. Also in Europe, the Spanish government refused to allow a democratic vote on the future of Catalunya, a decision causing months of instability in the region. Meanwhile in Thailand a military junta twice overthrew democratically elected governments and has changed the constitution in order to increase its own power. The authoritarian regime of Han Sen in Cambodia also dissolved the main opposition party and effectively implemented a one-man dictatorship. There are also large parts of the world such as China, Russia, Central and South East Asia, the Middle East and much of Africa which have consolidated authoritarian rule rather seeing it weaken.