Dharma

Dharma (/ˈdɑːrmə/; Sanskrit: धर्म, translit. dharma, pronounced [dʱəɾmə] ( listen); Pali: धम्म, translit. dhamma, translit. dhamma) is a key concept with multiple meanings in the Indian religions – Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. There is no single-word translation for dharma in Western languages.

listen); Pali: धम्म, translit. dhamma, translit. dhamma) is a key concept with multiple meanings in the Indian religions – Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. There is no single-word translation for dharma in Western languages.

In Hinduism, dharma signifies behaviours that are considered to be in accord with Ṛta, the order that makes life and universe possible, and includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living". In Buddhism, dharma means "cosmic law and order", and is also applied to the teachings of the Buddha. In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for "phenomena". Dharma in Jainism refers to the teachings of tirthankara (Jina) and the body of doctrine pertaining to the purification and moral transformation of human beings. For Sikhs, the word dharm means the path of righteousness and proper religious practice.

The word dharma was already in use in the historical Vedic religion, and its meaning and conceptual scope has evolved over several millennia. The antonym of dharma is adharma.

Dharma (/ˈdɑːrmə/; Sanskrit: धर्म, translit. dharma, pronounced [dʱəɾmə] (

In Hinduism, dharma signifies behaviours that are considered to be in accord with Ṛta, the order that makes life and universe possible, and includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living". In Buddhism, dharma means "cosmic law and order", and is also applied to the teachings of the Buddha. In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for "phenomena". Dharma in Jainism refers to the teachings of tirthankara (Jina) and the body of doctrine pertaining to the purification and moral transformation of human beings. For Sikhs, the word dharm means the path of righteousness and proper religious practice.

The word dharma was already in use in the historical Vedic religion, and its meaning and conceptual scope has evolved over several millennia. The antonym of dharma is adharma.

Etymology

In the Rigveda, the word appears as an n-stem, dhárman-, with a range of meanings encompassing "something established or firm" (in the literal sense of prods or poles). Figuratively, it means "sustainer" and "supporter" (of deities). It is semantically similar to the Greek Themis ("fixed decree, statute, law"). In Classical Sanskrit, the noun becomes thematic: dharma-.

The word dharma derives from Proto-Indo-European root

- dʰer- ("to hold"), which in Sanskrit is reflected as class-1 root[clarification needed] dhṛ. Etymologically it is related to Avestan dar- ("to hold"), Latin firmus ("steadfast, stable, powerful"), Lithuanian derė́ti ("to be suited, fit"), Lithuanian dermė ("agreement") and darna ("harmony") and Old Church Slavonic drъžati ("to hold, possess").

- Classical Sanskrit word dharmas would formally match with Latin o-stem firmus from Proto-Indo-European dʰer-mo-s "holding", were it not for its historical development from earlier Rigvedic n-stem.

Definition

Dharma is a concept of central importance in Indian philosophy and religion It has multiple meanings in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. It is difficult to provide a single concise definition for dharma, as the word has a long and varied history and straddles a complex set of meanings and interpretations. There is no equivalent single-word synonym for dharma in western languages.There have been numerous, conflicting attempts to translate ancient Sanskrit literature with the word dharma into German, English and French. The concept, claims Paul Horsch, has caused exceptional difficulties for modern commentators and translators. For example, while Grassmann's translation of Rig-veda identifies seven different meanings of dharma, Karl Friedrich Geldner in his translation of the Rig-veda employs 20 different translations for dharma, including meanings such as "law", "order", "duty", "custom", "quality", and "model", among others. However, the word dharma has become a widely accepted loanword in English, and is included in all modern unabridged English dictionaries.

The root of the word dharma is "dhri", which means "to support, hold, or bear". It is the thing that regulates the course of change by not participating in change, but that principle which remains constant Monier-Williams, the widely cited resource for definitions and explanation of Sanskrit words and concepts of Hinduism, offers numerous definitions of the word dharma: such as that which is established or firm, steadfast decree, statute, law, practice, custom, duty, right, justice, virtue, morality, ethics, religion, religious merit, good works, nature, character, quality, property. Yet, each of these definitions is incomplete, while combination of these translations do not convey the total sense of the word. In common parlance, dharma means "right way of living" and "path of rightness".

The meaning of the word dharma depends on the context, and its meaning has evolved as ideas of Hinduism have developed through history. In the earliest texts and ancient myths of Hinduism, dharma meant cosmic law, the rules that created the universe from chaos, as well as rituals; in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas and the Epics, the meaning became refined, richer, and more complex, and the word was applied to diverse contexts. In certain contexts, dharma designates human behaviours considered necessary for order of things in the universe, principles that prevent chaos, behaviours and action necessary to all life in nature, society, family as well as at the individual level. Dharma encompasses ideas such as duty, rights, character, vocation, religion, customs and all behaviour considered appropriate, correct or morally upright.

The antonym of dharma is adharma (Sanskrit: अधर्म), meaning that which is "not dharma". As with dharma, the word adharma includes and implies many ideas; in common parlance, adharma means that which is against nature, immoral, unethical, wrong or unlawful.

In Buddhism, dharma incorporates the teachings and doctrines of the founder of Buddhism, the Buddha.

History

According to the authoritative book History of Dharmasastra, in the hymns of the Rigveda the word dharma appears at least fifty-six times, as an adjective or noun. According to Paul Horsch, the word dharma has its origin in the myths of Vedic Hinduism. The Brahman (whom all the gods make up), claim the hymns of the Rig Veda, created the universe from chaos, they hold (dhar-) the earth and sun and stars apart, they support (dhar-) the sky away and distinct from earth, and they stabilise (dhar-) the quaking mountains and plains. The gods, mainly Indra, then deliver and hold order from disorder, harmony from chaos, stability from instability – actions recited in the Veda with the root of word dharma. In hymns composed after the mythological verses, the word dharma takes expanded meaning as a cosmic principle and appears in verses independent of gods. It evolves into a concept, claims Paul Horsch, that has a dynamic functional sense in Atharvaveda for example, where it becomes the cosmic law that links cause and effect through a subject. Dharma, in these ancient texts, also takes a ritual meaning. The ritual is connected to the cosmic, and "dharmani" is equated to ceremonial devotion to the principles that gods used to create order from disorder, the world from chaos. Past the ritual and cosmic sense of dharma that link the current world to mythical universe, the concept extends to ethical-social sense that links human beings to each other and to other life forms. It is here that dharma as a concept of law emerges in Hinduism.Dharma and related words are found in the oldest Vedic literature of Hinduism, in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, and the Epics; the word dharma also plays a central role in the literature of other Indian religions founded later, such as Buddhism and Jainism. According to Brereton, Dharman occurs 63 times in Rig-veda; in addition, words related to Dharman also appear in Rig-veda, for example once as dharmakrt, 6 times as satyadharman, and once as dharmavant, 4 times as dharman and twice as dhariman. There is no Iranian equivalent in old Persian for dharma, suggesting the word dharman had origins in Indo-Aryan culture outside of Persia, or it is a concept that is indigenous to India. However, ideas in parts overlapping to Dharma are found in other ancient cultures: such as Chinese Tao, Egyptian Maat, Sumerian Me.

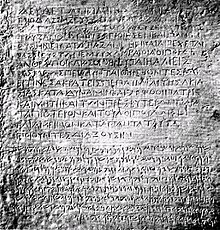

Eusebeia and dharma

Above rock inscription is from Indian Emperor Asoka, from 258 BC, and found in Afghanistan. The inscription renders the word Dharma in Sanskrit as Eusebeia in Greek, suggesting dharma in ancient India meant spiritual maturity, devotion, piety, duty towards and reverence for human community.[

In mid-20th century, an inscription of the Indian Emperor Asoka from the year 258 BC was discovered in Afghanistan. This rock inscription contained Sanskrit, Aramaic and Greek text. According to Paul Hacker, on the rock appears a Greek rendering for the Sanskrit word dharma: the word eusebeia. Scholars of Hellenistic Greece explain eusebeia as a complex concept. Eusebia means not only to venerate gods, but also spiritual maturity, a reverential attitude toward life, and includes the right conduct toward one's parents, siblings and children, the right conduct between husband and wife, and the conduct between biologically unrelated people. This rock inscription, concludes Paul Hacker, suggests dharma in India, about 2300 years ago, was a central concept and meant not only religious ideas, but ideas of right, of good, of one's duty toward the human community.

Rta, maya and dharma

The evolving literature of Hinduism linked dharma to two other important concepts: Ṛta and Māyā. Ṛta in Vedas is the truth and cosmic principle which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it.] Māyā in Rig-veda and later literature means illusion, fraud, deception, magic that misleads and creates disorder, thus is contrary to reality, laws and rules that establish order, predictability and harmony. Paul Horsch suggests Ṛta and dharma are parallel concepts, the former being a cosmic principle, the latter being of moral social sphere; while Māyā and dharma are also analogous concepts, the former being that which corrupts law and moral life, the later being that which strengthens law and moral life.Day proposes dharma is a manifestation of Ṛta, but suggests Ṛta may have been subsumed into a more complex concept of dharma, as the idea developed in ancient India over time in a nonlinear manner. The following verse from the Rigveda is an example where rta and dharma are linked:

O Indra, lead us on the path of Rta, on the right path over all evils...

— RV 10.133.6

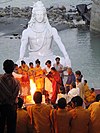

Hinduism

Dharma is an organising principle in Hinduism that applies to human beings in solitude, in their interaction with human beings and nature, as well as between inanimate objects, to all of cosmos and its parts. It refers to the order and customs which make life and universe possible, and includes behaviours, rituals, rules that govern society, and ethics. Hindu dharma includes the religious duties, moral rights and duties of each individual, as well as behaviours that enable social order, right conduct, and those that are virtuous. Dharma, according to Van Buitenen, is that which all existing beings must accept and respect to sustain harmony and order in the world. It is neither the act nor the result, but the natural laws that guide the act and create the result to prevent chaos in the world. It is innate characteristic, that makes the being what it is. It is, claims Van Buitenen, the pursuit and execution of one's nature and true calling, thus playing one's role in cosmic concert. In Hinduism, it is the dharma of the bee to make honey, of cow to give milk, of sun to radiate sunshine, of river to flow. In terms of humanity, dharma is the need for, the effect of and essence of service and interconnectedness of all life.In Hinduism, dharma includes two aspects – sanātana dharma, which is the overall, unchanging and abiding principals of dharma and is not subject to change, and yuga dharma, which is valid for a yuga, an epoch or age as established by Hindu tradition.

In Vedas and Upanishads

The history section of this article discusses the development of dharma concept in Vedas. This development continued in the Upanishads and later ancient scripts of Hinduism. In Upanishads, the concept of dharma continues as universal principle of law, order, harmony, and truth. It acts as the regulatory moral principle of the Universe. It is explained as law of righteousness and equated to satya (Sanskrit: सत्यं, truth), in hymn 1.4.14 of Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, as follows:धर्मः तस्माद्धर्मात् परं नास्त्य् अथो अबलीयान् बलीयाँसमाशँसते धर्मेण यथा राज्ञैवम् ।

यो वै स धर्मः सत्यं वै तत् तस्मात्सत्यं वदन्तमाहुर् धर्मं वदतीति धर्मं वा वदन्तँ सत्यं वदतीत्य् एतद्ध्येवैतदुभयं भवति ।।

Nothing is higher than dharma. The weak overcomes the stronger by dharma, as over a king. Truly that dharma is the Truth (Satya); Therefore, when a man speaks the Truth, they say, "He speaks the Dharma"; and if he speaks Dharma, they say, "He speaks the Truth!" For both are one.

— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4.xiv

In the Epics

The Hindu religion and philosophy, claims Daniel Ingalls, places major emphasis on individual practical morality. In the Sanskrit epics, this concern is omnipresent.In the Second Book of Ramayana, for example, a peasant asks the King to do what dharma morally requires of him, the King agrees and does so even though his compliance with the law of dharma costs him dearly. Similarly, dharma is at the centre of all major events in the life of Rama, Sita, and Lakshman in Ramayana, claims Daniel Ingalls. Each episode of Ramayana presents life situations and ethical questions in symbolic terms. The issue is debated by the characters, finally the right prevails over wrong, the good over evil. For this reason, in Hindu Epics, the good, morally upright, law-abiding king is referred to as "dharmaraja".

In Mahabharata, the other major Indian epic, similarly, dharma is central, and it is presented with symbolism and metaphors. Near the end of the epic, the god Yama, referred to as dharma in the text, is portrayed as taking the form of a dog to test the compassion of Yudishthira, who is told he may not enter paradise with such an animal, but refuses to abandon his companion, for which decision he is then praised by dharma. The value and appeal of the Mahabharata is not as much in its complex and rushed presentation of metaphysics in the 12th book, claims Ingalls, because Indian metaphysics is more eloquently presented in other Sanskrit scriptures; the appeal of Mahabharata, like Ramayana, is in its presentation of a series of moral problems and life situations, to which there are usually three answers given, according to Ingalls: one answer is of Bhima, which is the answer of brute force, an individual angle representing materialism, egoism, and self; the second answer is of Yudhishthira, which is always an appeal to piety and gods, of social virtue and of tradition; the third answer is of introspective Arjuna, which falls between the two extremes, and who, claims Ingalls, symbolically reveals the finest moral qualities of man. The Epics of Hinduism are a symbolic treatise about life, virtues, customs, morals, ethics, law, and other aspects of dharma. There is extensive discussion of dharma at the individual level in the Epics of Hinduism, observes Ingalls; for example, on free will versus destiny, when and why human beings believe in either, ultimately concluding that the strong and prosperous naturally uphold free will, while those facing grief or frustration naturally lean towards destiny. The Epics of Hinduism illustrate various aspects of dharma, they are a means of communicating dharma with metaphors.

According to 4th century Vatsyayana

According to Klaus Klostermaier, 4th century Hindu scholar Vātsyāyana explained dharma by contrasting it with adharma. Vātsyāyana suggested that dharma is not merely in one's actions, but also in words one speaks or writes, and in thought. According to Vātsyāyana:- Adharma of body: hinsa (violence), steya (steal, theft),

pratisiddha maithuna (sexual indulgence with someone other than one's

partner)

- Dharma of body: dana (charity), paritrana (succor of the distressed) and paricarana (rendering service to others)

- Adharma from words one speaks or writes: mithya (falsehood), parusa

(caustic talk), sucana (calumny) and asambaddha (absurd talk)

- Dharma from words one speaks or writes: satya (truth and facts),

hitavacana (talking with good intention), priyavacana (gentle, kind

talk), svadhyaya (self study)

- Adharma of mind: paradroha (ill will to anyone), paradravyabhipsa

(covetousness), nastikya (denial of the existence of morals and

religiosity)

- Dharma of mind: daya (compassion), asprha (disinterestedness), and sraddha (faith in others)

According to Patanjali Yoga

In the Yoga system the dharma is real; in the Vedanta it is unreal.Dharma is part of yoga, suggests Patanjali; the elements of Hindu dharma are the attributes, qualities and aspects of yoga. Patanjali explained dharma in two categories: yama (restraints) and niyama (observances).

The five yama, according to Patanjali, are: abstain from injury to all living creatures (ahimsa), abstain from falsehood (satya), abstain from unauthorised appropriation of things-of-value from another (acastrapurvaka), abstain from coveting or sexually cheating on your partner, and abstain from expecting or accepting gifts from others. The five yama apply in action, speech and mind. In explaining yama, Patanjali clarifies that certain professions and situations may require qualification in conduct. For example, a fisherman must injure a fish, but he must attempt to do this with least trauma to fish and the fisherman must try to injure no other creature as he fishes.

The five niyama (observances) are cleanliness by eating pure food and removing impure thoughts (such as arrogance or jealousy or pride), contentment in one's means, meditation and silent reflection regardless of circumstances one faces, study and pursuit of historic knowledge, and devotion of all actions to the Supreme Teacher to achieve perfection of concentration.

Sources

Dharma is an empirical and experiential inquiry for every man and woman, according to some texts of Hinduism. For example, Apastamba Dharmasutra states:Dharma and Adharma do not go around saying, "That is us." Neither do gods, nor gandharvas, nor ancestors declare what is Dharma and what is Adharma.In other texts, three sources and means to discover dharma in Hinduism are described. These, according to Paul Hacker, are: First, learning historical knowledge such as Vedas, Upanishads, the Epics and other Sanskrit literature with the help of one's teacher. Second, observing the behavior and example of good people. The third source applies when neither one's education nor example exemplary conduct is known. In this case, "atmatusti" is the source of dharma in Hinduism, that is the good person reflects and follows what satisfies his heart, his own inner feeling, what he feels driven to.

— Apastamba Dharmasutra

Dharma, life stages and social stratification

Some texts of Hinduism outline dharma for society and at the individual level. Of these, the most cited one is Manusmriti, which describes the four Varnas, their rights and duties. Most texts of Hinduism, however, discuss dharma with no mention of Varna (caste). Other dharma texts and Smritis differ from Manusmriti on the nature and structure of Varnas. Yet, other texts question the very existence of varna. Bhrigu, in the Epics, for example, presents the theory that dharma does not require any varnas. In practice, medieval India is widely believed to be a socially stratified society, with each social strata inheriting a profession and being endogamous. Varna was not absolute in Hindu dharma; individuals had the right to renounce and leave their Varna, as well as their asramas of life, in search of moksa. While neither Manusmriti nor succeeding Smritis of Hinduism ever use the word varnadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas), or varnasramadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas and asramas), the scholarly commentary on Manusmriti use these words, and thus associate dharma with varna system of India. In 6th century India, even Buddhist kings called themselves "protectors of varnasramadharma" – that is, dharma of varna and asramas of life.At the individual level, some texts of Hinduism outline four āśramas, or stages of life as individual's dharma. These are: (1) brahmacārya, the life of preparation as a student, (2) gṛhastha, the life of the householder with family and other social roles, (3) vānprastha or aranyaka, the life of the forest-dweller, transitioning from worldly occupations to reflection and renunciation, and (4) sannyāsa, the life of giving away all property, becoming a recluse and devotion to moksa, spiritual matters.

The four stages of life complete the four human strivings in life, according to Hinduism. Dharma enables the individual to satisfy the striving for stability and order, a life that is lawful and harmonious, the striving to do the right thing, be good, be virtuous, earn religious merit, be helpful to others, interact successfully with society. The other three strivings are Artha – the striving for means of life such as food, shelter, power, security, material wealth, etc.; Kama – the striving for sex, desire, pleasure, love, emotional fulfillment, etc.; and Moksa – the striving for spiritual meaning, liberation from life-rebirth cycle, self-realisation in this life, etc. The four stages are neither independent nor exclusionary in Hindu dharma.

Dharma and poverty

Dharma while being necessary for individual and society, is dependent on poverty and prosperity in a society, according to Hindu dharma scriptures. For example, according to Adam Bowles, Shatapatha Brahmana 11.1.6.24 links social prosperity and dharma through water. Waters come from rains, it claims; when rains are abundant there is prosperity on the earth, and this prosperity enables people to follow Dharma – moral and lawful life. In times of distress, of drought, of poverty, everything suffers including relations between human beings and the human ability to live according to dharma.In Rajadharmaparvan 91.34-8, the relationship between poverty and dharma reaches a full circle. A land with less moral and lawful life suffers distress, and as distress rises it causes more immoral and unlawful life, which further increases distress. Those in power must follow the raja dharma (that is, dharma of rulers), because this enables the society and the individual to follow dharma and achieve prosperity.

Dharma and law

The notion of dharma as duty or propriety is found in India's ancient legal and religious texts. In Hindu philosophy, justice, social harmony, and happiness requires that people live per dharma. The Dharmashastra is a record of these guidelines and rules. The available evidence suggest India once had a large collection of dharma related literature (sutras, shastras); four of the sutras survive and these are now referred to as Dharmasutras. Along with laws of Manu in Dharmasutras, exist parallel and different compendium of laws, such as the laws of Narada and other ancient scholars. These different and conflicting law books are neither exclusive, nor do they supersede other sources of dharma in Hinduism. These Dharmasutras include instructions on education of the young, their rites of passage, customs, religious rites and rituals, marital rights and obligations, death and ancestral rites, laws and administration of justice, crimes, punishments, rules and types of evidence, duties of a king, as well as morality.Buddhism

In Buddhism dharma means cosmic law and order, but is also applied to the teachings of the Buddha. In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for "phenomena". In East Asia, the translation for dharma is 法, pronounced fǎ in Mandarin, choe ཆོས་ in Tibetan, beop in Korean, hō in Japanese, and pháp in Vietnamese. However, the term dharma can also be transliterated from its original form.Buddha's teachings

For practicing Buddhists, references to "dharma" (dhamma in Pali) particularly as "the Dharma", generally means the teachings of the Buddha, commonly known throughout the East as Buddha-Dharma. It includes especially the discourses on the fundamental principles (such as the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path), as opposed to the parables and to the poems.The status of Dharma is regarded variably by different Buddhist traditions. Some regard it as an ultimate truth, or as the fount of all things which lie beyond the "three realms" (Sanskrit: tridhatu) and the "wheel of becoming" (Sanskrit: bhavachakra), somewhat like the pagan Greek and Christian logos: this is known as Dharmakaya (Sanskrit). Others, who regard the Buddha as simply an enlightened human being, see the Dharma as the essence of the "84,000 different aspects of the teaching" (Tibetan: chos-sgo brgyad-khri bzhi strong) that the Buddha gave to various types of people, based upon their individual propensities and capabilities.

Dharma refers not only to the sayings of the Buddha, but also to the later traditions of interpretation and addition that the various schools of Buddhism have developed to help explain and to expand upon the Buddha's teachings. For others still, they see the Dharma as referring to the "truth", or the ultimate reality of "the way that things really are" (Tib. Cho).

The Dharma is one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism in which practitioners of Buddhism seek refuge, or that upon which one relies for his or her lasting happiness. The Three Jewels of Buddhism are the Buddha, meaning the mind's perfection of enlightenment, the Dharma, meaning the teachings and the methods of the Buddha, and the Sangha, meaning the monastic community who provide guidance and support to followers of the Buddha.

Chan Buddhism

Dharma is employed in Ch'an in a specific context in relation to transmission of authentic doctrine, understanding and bodhi; recognised in Dharma transmission.Jainism

Jainism

The word Dharma in Jainism is found in all its key texts. It has a contextual meaning and refers to a number of ideas. In the broadest sense, it means the teachings of the Jinas, or teachings of any competing spiritual school, a supreme path, socio-religious duty, and that which is the highest mangala (holy).

The term dharma also has a specific ontological and soteriological meaning in Jainism, as a part of its theory of six dravya (substance or a reality). In the Jain tradition, existence consists of jiva (soul, atman) and ajiva (non-soul), the latter consisting of five categories: inert non-sentient atomic matter (pudgala), space (akasha), time (kala), principle of motion (dharma), and principle of rest (adharma). The use of the term dharma to mean motion and to refer to an ontological sub-category is peculiar to Jainism, and not found in the metaphysics of Buddhism and various schools of Hinduism.

The major Jain text, Tattvartha Sutra mentions Das-dharma with the meaning of "ten righteous virtues". These are forbearance, modesty, straightforwardness, purity, truthfulness, self-restraint, austerity, renunciation, non-attachment, and celibacy. Acārya Amṛtacandra, author of the Jain text, Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya writes:

A right believer should constantly meditate on virtues of dharma, like supreme modesty, in order to protect the soul from all contrary dispositions. He should also cover up the shortcomings of others.

— Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya (27)

Sikhism

Sikhism

For Sikhs, the word Dharm means the path of righteousness and proper religious practice. Guru Granth Sahib in hymn 1353 connotes dharma as duty. The 3HO movement in Western culture, which has incorporated certain Sikh beliefs, defines Sikh Dharma broadly as all that constitutes religion, moral duty and way of life.

Dharma in symbols

The wheel in the centre of India's flag symbolises Dharma.

The importance of dharma to Indian sentiments is illustrated by India's decision in 1947 to include the Ashoka Chakra, a depiction of the dharmachakra ( the "wheel of dharma"), as the central motif on its flag.