A comparison of the structures of the natural hormone estradiol (left) and one of the nonyl-phenols (right), an endocrine disruptor

Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that can interfere with endocrine (or hormone) systems at certain doses. These disruptions can cause cancerous tumors, birth defects, and other developmental disorders. Any system in the body controlled by hormones can be derailed by hormone disruptors. Specifically, endocrine disruptors may be associated with the development of learning disabilities, severe attention deficit disorder, cognitive and brain development problems; deformations of the body (including limbs); breast cancer, prostate cancer, thyroid and other cancers; sexual development problems such as feminizing of males or masculinizing effects on females, etc.

Recently the Endocrine Society released a statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) specifically listing obesity, diabetes, female reproduction, male reproduction, hormone-sensitive cancers in females, prostate cancer in males, thyroid, and neurodevelopment and neuroendocrine systems as being affected biological aspects of being exposed to EDCs. The critical period of development for most organisms is between the transition from a fertilized egg into a fully formed infant. As the cells begin to grow and differentiate, there are critical balances of hormones and protein changes that must occur. Therefore, a dose of disrupting chemicals may do substantial damage to a developing fetus. The same dose may not significantly affect adult mothers.

There has been controversy over endocrine disruptors, with some groups calling for swift action by regulators to remove them from the market, and regulators and other scientists calling for further study. Some endocrine disruptors have been identified and removed from the market (for example, a drug called diethylstilbestrol), but it is uncertain whether some endocrine disruptors on the market actually harm humans and wildlife at the doses to which wildlife and humans are exposed. Additionally, a key scientific paper, published in the journal Science, which helped launch the movement of those opposed to endocrine disruptors, was retracted and its author found to have committed scientific misconduct.

Found in many household and industrial products, endocrine disruptors are substances that "interfere with the synthesis, secretion, transport, binding, action, or elimination of natural hormones in the body that are responsible for development, behavior, fertility, and maintenance of homeostasis (normal cell metabolism)." They are sometimes also referred to as hormonally active agents, endocrine disrupting chemicals, or endocrine disrupting compounds. The variety of terms used to describe these substances reflects not only a range of meanings but a range of connotations, with endocrine disruptor emphasizing harmful effects, while hormonally active agent or xenohormone are more neutral, in keeping with the pharmacological principle the dose makes the poison.

Studies in cells and laboratory animals have shown that EDCs can cause adverse biological effects in animals, and low-level exposures may also cause similar effects in human beings. EDCs in the environment may also be related to reproductive and infertility problems in wildlife and bans and restrictions on their use has been associated with a reduction in health problems and the recovery of some wildlife populations.

History

The term endocrine disruptor was coined at the Wingspread Conference Centre in Wisconsin, in 1991. One of the early papers on the phenomenon was by Theo Colborn in 1993. In this paper, she stated that environmental chemicals disrupt the development of the endocrine system, and that effects of exposure during development are often permanent. Although the endocrine disruption has been disputed by some, work sessions from 1992 to 1999 have generated consensus statements from scientists regarding the hazard from endocrine disruptors, particularly in wildlife and also in humans.The Endocrine Society released a scientific statement outlining mechanisms and effects of endocrine disruptors on “male and female reproduction, breast development and cancer, prostate cancer, neuroendocrinology, thyroid, metabolism and obesity, and cardiovascular endocrinology,” and showing how experimental and epidemiological studies converge with human clinical observations “to implicate EDCs as a significant concern to public health.” The statement noted that it is difficult to show that endocrine disruptors cause human diseases, and it recommended that the precautionary principle should be followed. A concurrent statement expresses policy concerns.

Endocrine disrupting compounds encompass a variety of chemical classes, including drugs, pesticides, compounds used in the plastics industry and in consumer products, industrial by-products and pollutants, and even some naturally produced botanical chemicals. Some are pervasive and widely dispersed in the environment and may bioaccumulate. Some are persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and can be transported long distances across national boundaries and have been found in virtually all regions of the world, and may even concentrate near the North Pole, due to weather patterns and cold conditions. Others are rapidly degraded in the environment or human body or may be present for only short periods of time. Health effects attributed to endocrine disrupting compounds include a range of reproductive problems (reduced fertility, male and female reproductive tract abnormalities, and skewed male/female sex ratios, loss of fetus, menstrual problems); changes in hormone levels; early puberty; brain and behavior problems; impaired immune functions; and various cancers.

One example of the consequences of the exposure of developing animals, including humans, to hormonally active agents is the case of the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES), a nonsteroidal estrogen and not an environmental pollutant. Prior to its ban in the early 1970s, doctors prescribed DES to as many as five million pregnant women to block spontaneous abortion, an off-label use of this medication prior to 1947. It was discovered after the children went through puberty that DES affected the development of the reproductive system and caused vaginal cancer. The relevance of the DES saga to the risks of exposure to endocrine disruptors is questionable, as the doses involved are much higher in these individuals than in those due to environmental exposures.

Aquatic life subjected to endocrine disruptors in an urban effluent have experienced decreased levels of serotonin and increased feminization.

In 2013 the WHO and the United Nations Environment Programme released a study, the most comprehensive report on EDCs to date, calling for more research to fully understand the associations between EDCs and the risks to health of human and animal life. The team pointed to wide gaps in knowledge and called for more research to obtain a fuller picture of the health and environmental impacts of endocrine disruptors. To improve global knowledge the team has recommended:

- Testing: known EDCs are only the 'tip of the iceberg' and more comprehensive testing methods are required to identify other possible endocrine disruptors, their sources, and routes of exposure.

- Research: more scientific evidence is needed to identify the effects of mixtures of EDCs on humans and wildlife (mainly from industrial by-products) to which humans and wildlife are increasingly exposed.

- Reporting: many sources of EDCs are not known because of insufficient reporting and information on chemicals in products, materials and goods.

- Collaboration: more data sharing between scientists and between countries can fill gaps in data, primarily in developing countries and emerging economies.

Endocrine system

Endocrine systems are found in most varieties of animals. The endocrine system consists of glands that secrete hormones, and receptors that detect and react to the hormones.Hormones travel throughout the body and act as chemical messengers. Hormones interface with cells that contain matching receptors in or on their surfaces. The hormone binds with the receptor, much like a key would fit into a lock. The endocrine system regulates adjustments through slower internal processes, using hormones as messengers. The endocrine system secretes hormones in response to environmental stimuli and to orchestrate developmental and reproductive changes. The adjustments brought on by the endocrine system are biochemical, changing the cell's internal and external chemistry to bring about a long term change in the body. These systems work together to maintain the proper functioning of the body through its entire life cycle. Sex steroids such as estrogens and androgens, as well as thyroid hormones, are subject to feedback regulation, which tends to limit the sensitivity of these glands.

Hormones work at very small doses (part per billion ranges). Endocrine disruption can thereby also occur from low-dose exposure to exogenous hormones or hormonally active chemicals such as bisphenol A. These chemical can bind to receptors for other hormonally mediated processes. Furthermore, since endogenous hormones are already present in the body in biologically active concentrations, additional exposure to relatively small amounts of exogenous hormonally active substances can disrupt the proper functioning of the body's endocrine system. Thus, an endocrine disruptor can elicit adverse effects at much lower doses than a toxicity, acting through a different mechanism.

The timing of exposure is also critical. Most critical stages of development occur in utero, where the fertilized egg divides, rapidly developing every structure of a fully formed baby, including much of the wiring in the brain. Interfering with the hormonal communication in utero can have profound effects both structurally and toward brain development. Depending on the stage of reproductive development, interference with hormonal signaling can result in irreversible effects not seen in adults exposed to the same dose for the same length of time. Experiments with animals have identified critical developmental time points in utero and days after birth when exposure to chemicals that interfere with or mimic hormones have adverse effects that persist into adulthood. Disruption of thyroid function early in development may be the cause of abnormal sexual development in both males and females early motor development impairment, and learning disabilities.

There are studies of cell cultures, laboratory animals, wildlife, and accidentally exposed humans that show that environmental chemicals cause a wide range of reproductive, developmental, growth, and behavior effects, and so while "endocrine disruption in humans by pollutant chemicals remains largely undemonstrated, the underlying science is sound and the potential for such effects is real." While compounds that produce estrogenic, androgenic, antiandrogenic, and antithyroid actions have been studied, less is known about interactions with other hormones.

The interrelationship between exposures to chemicals and health effects are rather complex. It is hard to definitively link a particular chemical with a specific health effect, and exposed adults may not show any ill effects. But, fetuses and embryos, whose growth and development are highly controlled by the endocrine system, are more vulnerable to exposure and may suffer overt or subtle lifelong health and/or reproductive abnormalities. Prebirth exposure, in some cases, can lead to permanent alterations and adult diseases.

Some in the scientific community are concerned that exposure to endocrine disruptors in the womb or early in life may be associated with neurodevelopmental disorders including reduced IQ, ADHD, and autism. Certain cancers and uterine abnormalities in women are associated with exposure to Diethylstilbestrol (DES) in the womb due to DES used as a medical treatment.

In another case, phthalates in pregnant women’s urine was linked to subtle, but specific, genital changes in their male infants – a shorter, more female-like anogenital distance and associated incomplete descent of testes and a smaller scrotum and penis. The science behind this study has been questioned by phthalate industry consultants. As of June 2008, there are only five studies of anogenital distance in humans, and one researcher has stated "Whether AGD measures in humans relate to clinically important outcomes, however, remains to be determined, as does its utility as a measure of androgen action in epidemiologic studies."

U-shaped dose-response curve

Most toxicants, including endocrine disruptors, have been claimed to follow a U-shaped dose response curve. This means that very low and very high levels have more effects than mid-level exposure to a toxicant. Endocrine disrupting effects have been noted in animals exposed to environmentally relevant levels of some chemicals. For example, a common flame retardant, BDE-47, affects the reproductive system and thyroid gland of female rats in doses of the order of those to which humans are exposed. Low concentrations of endocrine disruptors can also have synergistic effects in amphibians, but it is not clear that this is an effect mediated through the endocrine system.Critics have argued that data suggest that the amounts of chemicals in the environment are too low to cause an effect. A consensus statement by the Learning and Developmental Disabilities Initiative argued that "The very low-dose effects of endocrine disruptors cannot be predicted from high-dose studies, which contradicts the standard 'dose makes the poison' rule of toxicology. Nontraditional dose-response curves are referred to as nonmonotonic dose response curves."

The dosage objection could also be overcome if low concentrations of different endocrine disruptors are synergistic. This paper was published in Science in June 1996, and was one reason for the passage of the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996. The results could not be confirmed with the same and alternative methodologies, and the original paper was retracted, with Arnold found to have committed scientific misconduct by the United States Office of Research Integrity.

It has been claimed that Tamoxifen and some phthalates have fundamentally different (and harmful) effects on the body at low doses than at high doses.

Routes of exposure

Food is a major mechanism by which people are exposed to pollutants. Diet is thought to account for up to 90% of a person's PCB and DDT body burden. In a study of 32 different common food products from three grocery stores in Dallas, fish and other animal products were found to be contaminated with PBDE. Since these compounds are fat soluble, it is likely they are accumulating from the environment in the fatty tissue of animals we eat. Some suspect fish consumption is a major source of many environmental contaminants. Indeed, both wild and farmed salmon from all over the world have been shown to contain a variety of man-made organic compounds.With the increase in household products containing pollutants and the decrease in the quality of building ventilation, indoor air has become a significant source of pollutant exposure. Residents living in homes with wood floors treated in the 1960s with PCB-based wood finish have a much higher body burden than the general population. A study of indoor house dust and dryer lint of 16 homes found high levels of all 22 different PBDE congeners tested for in all samples. Recent studies suggest that contaminated house dust, not food, may be the major source of PBDE in our bodies. One study estimated that ingestion of house dust accounts for up to 82% of our PBDE body burden.

Research conducted by the Environmental Working Group found that 19 out of 20 children tested had levels of PBDE in their blood 3.5 times higher than the amount in their mothers' blood. It has been shown that contaminated house dust is a primary source of lead in young children's bodies. It may be that babies and toddlers ingest more contaminated house dust than the adults they live with, and therefore have much higher levels of pollutants in their systems.

Consumer goods are another potential source of exposure to endocrine disruptors. An analysis of the composition of 42 household cleaning and personal care products versus 43 "chemical free" products has been performed. The products contained 55 different chemical compounds: 50 were found in the 42 conventional samples representing 170 product types, while 41 were detected in 43 "chemical free" samples representing 39 product types. Parabens, a class of chemicals that has been associated with reproductive-tract issues, were detected in seven of the "chemical free" products, including three sunscreens that did not list parabens on the label. Vinyl products such as shower curtains were found to contain more than 10% by weight of the compound DEHP, which when present in dust has been associated with asthma and wheezing in children. The risk of exposure to EDCs increases as products, both conventional and "chemical free," are used in combination. "If a consumer used the alternative surface cleaner, tub and tile cleaner, laundry detergent, bar soap, shampoo and conditioner, facial cleanser and lotion, and toothpaste [he or she] would potentially be exposed to at least 19 compounds: 2 parabens, 3 phthalates, MEA, DEA, 5 alkylphenols, and 7 fragrances."

An analysis of the endocrine disrupting chemicals in Old Order Mennonite women in mid-pregnancy determined that they have much lower levels in their systems than the general population. Mennonites eat mostly fresh, unprocessed foods, farm without pesticides, and use few or no cosmetics or personal care products. One woman who had reported using hairspray and perfume had high levels of monoethyl phthalate, while the other women all had levels below detection. Three women who reported being in a car or truck within 48 hours of providing a urine sample had higher levels of diethylhexyl phthalate which is found in polyvinyl chloride, and is used in car interiors.

Additives added to plastics during manufacturing may leach into the environment after the plastic item is discarded; additives in microplastics in the ocean leach into ocean water and in plastics in landfills may escape and leach into the soil and then into groundwater.

Types

All people are exposed to chemicals with estrogenic effects in their everyday life, because endocrine disrupting chemicals are found in low doses in thousands of products. Chemicals commonly detected in people include DDT, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB's), bisphenol A (BPA), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE's), and a variety of phthalates. In fact, almost all plastic products, including those advertised as "BPA free", have been found to leach endocrine-disrupting chemicals. In a 2011, study it was found that some "BPA-free" products released more endocrine active chemicals than the BPA-containing products. Other forms of endocrine disruptors are phytoestrogens (plant hormones).Xenoestrogens

Xenoestrogens are a type of xenohormone that imitates estrogen. Synthetic xenoestrogens include widely used industrial compounds, such as PCBs, BPA and phthalates, which have estrogenic effects on a living organism.Alkylphenols

Alkylphenols are xenoestrogens. The European Union has implemented sales and use restrictions on certain applications in which nonylphenols are used because of their alleged "toxicity, persistence, and the liability to bioaccumulate" but the United States Environmental Protections Agency (EPA) has taken a slower approach to make sure that action is based on "sound science".The long-chain alkylphenols are used extensively as precursors to the detergents, as additives for fuels and lubricants, polymers, and as components in phenolic resins. These compounds are also used as building block chemicals that are also used in making fragrances, thermoplastic elastomers, antioxidants, oil field chemicals and fire retardant materials. Through the downstream use in making alkylphenolic resins, alkylphenols are also found in tires, adhesives, coatings, carbonless copy paper and high performance rubber products. They have been used in industry for over 40 years.

Certain alkylphenols are degradation products from nonionic detergents. Nonylphenol is considered to be a low-level endocrine disruptor owing to its tendency to mimic estrogen.

Bisphenol A (BPA)

Bisphenol A chemical structure

Bisphenol A is commonly found in plastic bottles, plastic food containers, dental materials, and the linings of metal food and infant formula cans. Another exposure comes from receipt paper commonly used at grocery stores and restaurants, because today the paper is commonly coated with a BPA containing clay for printing purposes.

BPA is a known endocrine disruptor, and numerous studies have found that laboratory animals exposed to low levels of it have elevated rates of diabetes, mammary and prostate cancers, decreased sperm count, reproductive problems, early puberty, obesity, and neurological problems. Early developmental stages appear to be the period of greatest sensitivity to its effects, and some studies have linked prenatal exposure to later physical and neurological difficulties. Regulatory bodies have determined safety levels for humans, but those safety levels are currently being questioned or are under review as a result of new scientific studies. A 2011 study that investigated the number of chemicals pregnant women are exposed to in the U.S. found BPA in 96% of women.

In 2010 the World Health Organization expert panel recommended no new regulations limiting or banning the use of bisphenol A, stating that "initiation of public health measures would be premature."

In August 2008, the U.S. FDA issued a draft reassessment, reconfirming their initial opinion that, based on scientific evidence, it is safe. However, in October 2008, FDA's advisory Science Board concluded that the Agency's assessment was "flawed" and hadn't proven the chemical to be safe for formula-fed infants. In January 2010, the FDA issued a report indicating that, due to findings of recent studies that used novel approaches in testing for subtle effects, both the National Toxicology Program at the National Institutes of Health as well as the FDA have some level of concern regarding the possible effects of BPA on the brain and behavior of fetuses, infants and younger children. In 2012 the FDA did ban the use of BPA in baby bottles, however the Environmental Working Group called the ban "purely cosmetic". In a statement they said, “If the agency truly wants to prevent people from being exposed to this toxic chemical associated with a variety of serious and chronic conditions it should ban its use in cans of infant formula, food and beverages." The Natural Resources Defense Council called the move inadequate saying, the FDA needs to ban BPA from all food packaging. In a statement a FDA spokesman said the agency's action was not based on safety concerns and that "the agency continues to support the safety of BPA for use in products that hold food."

Bisphenol S (BPS)

Bisphenol S is an analog of bisphenol A. It is commonly found in thermal receipts, plastics, and household dust. Traces of BPS have also been found in personal care products. It is more presently being used because of the ban of BPA. BPS is used in place of BPA in “BPA free” items. However BPS has been shown to be as much of an endocrine disruptor as BPA.DDT

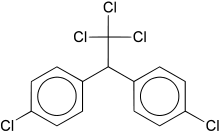

DDT Chemical structure

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was first used as a pesticide against Colorado potato beetles on crops beginning in 1936. An increase in the incidence of malaria, epidemic typhus, dysentery, and typhoid fever led to its use against the mosquitoes, lice, and houseflies that carried these diseases. Before World War II, pyrethrum, an extract of a flower from Japan, had been used to control these insects and the diseases they can spread. During World War II, Japan stopped exporting pyrethrum, forcing the search for an alternative. Fearing an epidemic outbreak of typhus, every British and American soldier was issued DDT, who used it to routinely dust beds, tents, and barracks all over the world.

DDT was approved for general, non-military use after the war ended. It became used worldwide to increase monoculture crop yields that were threatened by pest infestation, and to reduce the spread of malaria which had a high mortality rate in many parts of the world. Its use for agricultural purposes has since been prohibited by national legislation of most countries, while its use as a control against malaria vectors is permitted, as specifically stated by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.

As early as 1946, the harmful effects of DDT on bird, beneficial insects, fish, and marine invertebrates were seen in the environment. The most infamous example of these effects were seen in the eggshells of large predatory birds, which did not develop to be thick enough to support the adult bird sitting on them. Further studies found DDT in high concentrations in carnivores all over the world, the result of biomagnification through the food chain. Twenty years after its widespread use, DDT was found trapped in ice samples taken from Antarctic snow, suggesting wind and water are another means of environmental transport. Recent studies show the historical record of DDT deposition on remote glaciers in the Himalayas.

More than sixty years ago when biologists began to study the effects of DDT on laboratory animals, it was discovered that DDT interfered with reproductive development. Recent studies suggest DDT may inhibit the proper development of female reproductive organs that adversely affects reproduction into maturity. Additional studies suggest that a marked decrease in fertility in adult males may be due to DDT exposure. Most recently, it has been suggested that exposure to DDT in utero can increase a child's risk of childhood obesity. DDT is still used as anti-malarial insecticide in Africa and parts of Southeast Asia in limited quantities.

Polychlorinated biphenyls

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a class of chlorinated compounds used as industrial coolants and lubricants. PCBs are created by heating benzene, a byproduct of gasoline refining, with chlorine. They were first manufactured commercially by the Swann Chemical Company in 1927. In 1933, the health effects of direct PCB exposure was seen in those who worked with the chemicals at the manufacturing facility in Alabama. In 1935, Monsanto acquired the company, taking over US production and licensing PCB manufacturing technology internationally.General Electric was one of the largest US companies to incorporate PCBs into manufactured equipment. Between 1952 and 1977, the New York GE plant had dumped more than 500,000 pounds of PCB waste into the Hudson River. PCBs were first discovered in the environment far from its industrial use by scientists in Sweden studying DDT.

The effects of acute exposure to PCBs were well known within the companies who used Monsanto's PCB formulation who saw the effects on their workers who came into contact with it regularly. Direct skin contact results in a severe acne-like condition called chloracne. Exposure increases the risk of skin cancer, liver cancer, and brain cancer. Monsanto tried for years to downplay the health problems related to PCB exposure in order to continue sales.

The detrimental health effects of PCB exposure to humans became undeniable when two separate incidents of contaminated cooking oil poisoned thousands of residents in Japan (Yushō disease, 1968) and Taiwan (Yu-cheng disease, 1979), leading to a worldwide ban on PCB use in 1977. Recent studies show the endocrine interference of certain PCB congeners is toxic to the liver and thyroid, increases childhood obesity in children exposed prenatally, and may increase the risk of developing diabetes.

PCBs in the environment may also be related to reproductive and infertility problems in wildlife. In Alaska it is thought that they may contribute to reproductive defects, infertility and antler malformation in some deer populations. Declines in the populations of otters and sea lions may also be partially due to their exposure to PCBs, the insecticide DDT, other persistent organic pollutants. Bans and restrictions on the use of EDCs have been associated with a reduction in health problems and the recovery of some wildlife populations.

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) are a class of compounds found in flame retardants used in plastic cases of televisions and computers, electronics, carpets, lighting, bedding, clothing, car components, foam cushions and other textiles. Potential health concern: PBDE's are structurally very similar to Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and have similar neurotoxic effects. Research has correlated halogenated hydrocarbons, such as PCBs, with neurotoxicity. PBDEs are similar in chemical structure to PCBs, and it has been suggested that PBDEs act by the same mechanism as PCBs.In the 1930s and 1940s, the plastics industry developed technologies to create a variety of plastics with broad applications. Once World War II began, the US military used these new plastic materials to improve weapons, protect equipment, and to replace heavy components in aircraft and vehicles. After WWII, manufacturers saw the potential plastics could have in many industries, and plastics were incorporated into new consumer product designs. Plastics began to replace wood and metal in existing products as well, and today plastics are the most widely used manufacturing materials.

By the 1960s, all homes were wired with electricity and had numerous electrical appliances. Cotton had been the dominant textile used to produce home furnishings, but now home furnishings were composed of mostly synthetic materials. More than 500 billion cigarettes were consumed each year in the 1960s, as compared to less than 3 billion per year in the beginning of the twentieth century. When combined with high density living, the potential for home fires was higher in the 1960s than it had ever been in the US. By the late 1970s, approximately 6000 people in the US died each year in home fires.

In 1972, in response to this situation, the National Commission on Fire Prevention and Control was created to study the fire problem in the US. In 1973 they published their findings in America Burning, a 192-page report that made recommendations to increase fire prevention. Most of the recommendations dealt with fire prevention education and improved building engineering, such as the installation of fire sprinklers and smoke detectors. The Commission expected that with the recommendations, a 5% reduction in fire losses could be expected each year, halving the annual losses within 14 years.

Historically, treatments with alum and borax were used to reduce the flammability of fabric and wood, as far back as Roman times. Since it is a non-absorbent material once created, flame retardant chemicals are added to plastic during the polymerization reaction when it is formed. Organic compounds based on halogens like bromine and chlorine are used as the flame retardant additive in plastics, and in fabric based textiles as well. The widespread use of brominated flame retardants may be due to the push from Great Lakes Chemical Corporation (GLCC) to profit from its huge investment in bromine. In 1992, the world market consumed approximately 150,000 tonnes of bromine-based flame retardants, and GLCC produced 30% of the world supply.

PBDEs have the potential to disrupt thyroid hormone balance and contribute to a variety of neurological and developmental deficits, including low intelligence and learning disabilities. Many of the most common PBDE's were banned in the European Union in 2006. Studies with rodents have suggested that even brief exposure to PBDEs can cause developmental and behavior problems in juvenile rodents and exposure interferes with proper thyroid hormone regulation.

Phthalates

Phthalates are found in some soft toys, flooring, medical equipment, cosmetics and air fresheners. They are of potential health concern because they are known to disrupt the endocrine system of animals, and some research has implicated them in the rise of birth defects of the male reproductive system.Although an expert panel has concluded that there is "insufficient evidence" that they can harm the reproductive system of infants, California, Washington state and Europe have banned them from toys. One phthalate, bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), used in medical tubing, catheters and blood bags, may harm sexual development in male infants. In 2002, the Food and Drug Administration released a public report which cautioned against exposing male babies to DEHP. Although there are no direct human studies the FDA report states: "Exposure to DEHP has produced a range of adverse effects in laboratory animals, but of greatest concern are effects on the development of the male reproductive system and production of normal sperm in young animals. In view of the available animal data, precautions should be taken to limit the exposure of the developing male to DEHP". Similarly, phthalates may play a causal role in disrupting masculine neurological development when exposed prenatally.

Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) has also disrupted insulin and glucagon signaling in animal models.

Perfluorooctanoic acid

PFOA exerts hormonal effects including alteration of thyroid hormone levels. Blood serum levels of PFOA were associated with an increased time to pregnancy — or "infertility" — in a 2009 study. PFOA exposure is associated with decreased semen quality. PFOA appeared to act as an endocrine disruptor by a potential mechanism on breast maturation in young girls. A C8 Science Panel status report noted an association between exposure in girls and a later onset of puberty.Other suspected endocrine disruptors

Some other examples of putative EDCs are polychlorinated dibenzo-dioxins (PCDDs) and -furans (PCDFs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), phenol derivatives and a number of pesticides (most prominent being organochlorine insecticides like endosulfan, kepone (chlordecone) and DDT and its derivatives, the herbicide atrazine, and the fungicide vinclozolin), the contraceptive 17-alpha ethinylestradiol, as well as naturally occurring phytoestrogens such as genistein and mycoestrogens such as zearalenone.The molting in crustaceans is an endocrine-controlled process. In the marine penaeid shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei, exposure to endosulfan resulted increased susceptibility to acute toxicity and increased mortalities in the postmolt stage of the shrimp.

Many sunscreens contain oxybenzone, a chemical blocker that provides broad-spectrum UV coverage, yet is subject to a lot of controversy due its potential estrogenic effect in humans.

Tributyltin (TBT) are organotin compounds that for 40 years TBT was used as a biocide in anti-fouling paint, commonly known as bottom paint. TBT has been shown to impact invertebrate and vertebrate development, disrupting the endocrine system, resulting in masculinization, lower survival rates, as well as many health problems in mammals.

Temporal trends of body burden

Since being banned, the average human body burdens of DDT and PCB have been declining. Since their ban in 1972, the PCB body burden in 2009 is one-hundredth of what it was in the early 1980s. On the other hand, monitoring programs of European breast milk samples have shown that PBDE levels are increasing. An analysis of PBDE content in breast milk samples from Europe, Canada, and the US shows that levels are 40 times higher for North American women than for Swedish women, and that levels in North America are doubling every two to six years.Legal approach

United States

The multitude of possible endocrine disruptors are technically regulated in the United States by many laws, including: the Toxic Substances Control Act, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and the Clean Air Act.The Congress of the United States has improved the evaluation and regulation process of drugs and other chemicals. The Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 and the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1996 simultaneously provided the first legislative direction requiring the EPA to address endocrine disruption through establishment of a program for screening and testing of chemical substances.

In 1998, the EPA announced the Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program by establishment of a framework for priority setting, screening and testing more than 85,000 chemicals in commerce. The basic concept behind the program is that prioritization will be based on existing information about chemical uses, production volume, structure-activity and toxicity. Screening is done by use of in vitro test systems (by examining, for instance, if an agent interacts with the estrogen receptor or the androgen receptor) and via the use of in animal models, such as development of tadpoles and uterine growth in prepubertal rodents. Full scale testing will examine effects not only in mammals (rats) but also in a number of other species (frogs, fish, birds and invertebrates). Since the theory involves the effects of these substances on a functioning system, animal testing is essential for scientific validity, but has been opposed by animal rights groups. Similarly, proof that these effects occur in humans would require human testing, and such testing also has opposition.

After failing to meet several deadlines to begin testing, the EPA finally announced that they were ready to begin the process of testing dozens of chemical entities that are suspected endocrine disruptors early in 2007, eleven years after the program was announced. When the final structure of the tests was announced there was objection to their design. Critics have charged that the entire process has been compromised by chemical company interference. In 2005, the EPA appointed a panel of experts to conduct an open peer-review of the program and its orientation. Their results found that "the long-term goals and science questions in the EDC program are appropriate", however this study was conducted over a year before the EPA announced the final structure of the screening program.

Europe

In 2013, a number of pesticides containing endocrine disrupting chemicals were in draft EU criteria to be banned. On the 2nd May, US TTIP negotiators insisted the EU drop the criteria. They stated that a risk-based approach should be taken on regulation. Later the same day Catherine Day wrote to Karl Falkenberg asking for the criteria to be removed.The European Commission had been to set criteria by December 2013 identifying endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in thousands of products — including disinfectants, pesticides and toiletries — that have been linked to cancers, birth defects and development disorders in children. However, the body delayed the process, prompting Sweden to state that it would sue the commission in May 2014 — blaming chemical industry lobbying for the disruption.

“This delay is due to the European chemical lobby, which put pressure again on different commissioners. Hormone disrupters are becoming a huge problem. In some places in Sweden we see double-sexed fish. We have scientific reports on how this affects fertility of young boys and girls, and other serious effects,” Swedish Environment Minister Lena Ek told the AFP, noting that Denmark had also demanded action.

In November 2014, the Copenhagen-based Nordic Council of Ministers released its own independent report that estimated the impact of environmental EDCs on male reproductive health, and the resulting cost to public health systems. It concluded that EDCs likely cost health systems across the EU anywhere from 59 million to 1.18 billion Euros a year, noting that even this represented only "a fraction of the endocrine related diseases".

Environmental and human body cleanup

There is evidence that once a pollutant is no longer in use, or once its use is heavily restricted, the human body burden of that pollutant declines. Through the efforts of several large-scale monitoring programs, the most prevalent pollutants in the human population are fairly well known. The first step in reducing the body burden of these pollutants is eliminating or phasing out their production.The second step toward lowering human body burden is awareness of and potentially labeling foods that are likely to contain high amounts of pollutants. This strategy has worked in the past - pregnant and nursing women are cautioned against eating seafood that is known to accumulate high levels of mercury. Ideally, a certification process should be in place to routinely test animal products for POP concentrations. This would help the consumer identify which foods have the highest levels of pollutants.

The most challenging aspect of this problem is discovering how to eliminate these compounds from the environment and where to focus remediation efforts. Even pollutants no longer in production persist in the environment, and bio-accumulate in the food chain. An understanding of how these chemicals, once in the environment, move through ecosystems, is essential to designing ways to isolate and remove them. Working backwards through the food chain may help to identify areas to prioritize for remediation efforts. This may be extremely challenging for contaminated fish and marine mammals that have a large habitat and who consume fish from many different areas throughout their lives.

Many persistent organic compounds, PCB, DDT and PBDE included, accumulate in river and marine sediments. Several processes are currently being used by the EPA to clean up heavily polluted areas, as outlined in their Green Remediation program.

One of the most interesting ways is the utilization of naturally occurring microbes that degrade PCB congeners to remediate contaminated areas.

There are many success stories of cleanup efforts of large heavily contaminated Superfund sites. A 10-acre (40,000 m2) landfill in Austin, Texas contaminated with illegally dumped VOCs was restored in a year to a wetland and educational park.

A US uranium enrichment site that was contaminated with uranium and PCBs was cleaned up with high tech equipment used to find the pollutants within the soil. The soil and water at a polluted wetlands site were cleaned of VOCs, PCBs and lead, native plants were installed as biological filters, and a community program was implemented to ensure ongoing monitoring of pollutant concentrations in the area. These case studies are encouraging due to the short amount of time needed to remediate the site and the high level of success achieved.

Studies suggest that bisphenol A, certain PCBs, and phthalate compounds are preferentially eliminated from the human body through sweat.

Economic effects

Human exposure may cause some health effects, such as lower IQ and adult obesity. These effects may lead to lost productivity, disability, or premature death in some people. One source estimated that, within the European Union, this economic effect might have about twice the economic impact as the effects caused by mercury and lead contamination.The socio-economic burden of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDC)-associated health effects for the European Union was estimated based on currently available literature and considering the uncertainties with respect to causality with EDCs and corresponding health-related costs to be in the range of €46 billion to €288 billion per year.