A worship service at Lakewood Church, Houston, Texas, in 2013

Evangelicalism (/ˌiːvænˈdʒɛlɪkəlɪzəm,

Its origins are usually traced to 1738, with various theological streams contributing to its foundation, including English Methodism, the Moravian Church (in particular its bishop Nicolaus Zinzendorf and his community at Herrnhut), and German Lutheran Pietism. Preeminently, John Wesley and other early Methodists were at the root of sparking this new movement during the First Great Awakening. Today, evangelicals are found across many Protestant branches, as well as in various denominations not subsumed to a specific branch. Among leaders and major figures of the evangelical Protestant movement were John Wesley, George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, Billy Graham, Bill Bright, Harold John Ockenga, John Stott and Martyn Lloyd-Jones. The movement gained great momentum during the 18th and 19th centuries with the Great Awakenings in Great Britain and the United States.

The United States has the largest concentration of evangelicals in the world. American evangelicals are a quarter of the nation's population and its single largest religious group. In Great Britain, evangelicals are represented mostly in the Methodist Church, Baptist communities, and among evangelical Anglicans.

While evangelicalism is on the rise globally, developing countries have particularly embraced it; it is the fastest growing portion of Christianity.

Terminology

The word evangelical has its etymological roots in the Greek word for "gospel" or "good news": εὐαγγέλιον euangelion, from eu "good", angel- the stem of, among other words, angelos "messenger, angel", and the neuter suffix -ion. By the English Middle Ages, the term had expanded semantically to include not only the message, but also the New Testament which contained the message, as well as more specifically the Gospels, which portray the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. The first published use of evangelical in English was in 1531, when William Tyndale wrote "He exhorteth them to proceed constantly in the evangelical truth." One year later Sir Thomas More wrote the earliest recorded use in reference to a theological distinction when he spoke of "Tyndale [and] his evangelical brother Barns".During the Reformation, Protestant theologians embraced the term as referring to "gospel truth". Martin Luther referred to the evangelische Kirche ("evangelical church") to distinguish Protestants from Catholics in the Roman Catholic Church. Into the 21st century, evangelical has continued in use as a synonym for (mainline) Protestant in continental Europe, and elsewhere. This usage is reflected in the names of Protestant denominations, such as the Evangelical Church in Germany (a union of Lutheran and Reformed churches) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

In the English-speaking world, evangelical was commonly applied to describe the series of revival movements that occurred in Britain and North America during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Christian historian David Bebbington writes that, "Although 'evangelical', with a lower-case initial, is occasionally used to mean 'of the gospel', the term 'Evangelical', with a capital letter, is applied to any aspect of the movement beginning in the 1730s." According to the Oxford English Dictionary, evangelicalism was first used in 1831.

The term may also be used outside any religious context to characterize a generic missionary, reforming, or redeeming impulse or purpose. For example, the Times Literary Supplement refers to "the rise and fall of evangelical fervor within the Socialist movement".

Characteristics

Children worshipping at the Harvestime Church of Eau Claire, Wisconsin

One influential definition of evangelicalism has been proposed by historian David Bebbington. Bebbington notes four distinctive aspects of evangelical faith: conversionism, biblicism, crucicentrism, and activism, noting, "Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis of Evangelicalism."

Conversionism, or belief in the necessity of being "born again", has been a constant theme of evangelicalism since its beginnings. To evangelicals, the central message of the gospel is justification by faith in Christ and repentance, or turning away, from sin. Conversion differentiates the Christian from the non-Christian, and the change in life it leads to is marked by both a rejection of sin and a corresponding personal holiness of life. A conversion experience can be emotional, including grief and sorrow for sin followed by great relief at receiving forgiveness. The stress on conversion differentiates evangelicalism from other forms of Protestantism by the associated belief that an assurance of salvation will accompany conversion. Among evangelicals, individuals have testified to both sudden and gradual conversions.

Biblicism is reverence for the Bible and a high regard for biblical authority. All evangelicals believe in biblical inspiration, though they disagree over how this inspiration should be defined. Many evangelicals believe in biblical inerrancy, while other evangelicals believe in biblical infallibility.

Crucicentrism is the centrality that evangelicals give to the Atonement, the saving death and resurrection of Jesus, that offers forgiveness of sins and new life. This is understood most commonly in terms of a substitutionary atonement, in which Christ died as a substitute for sinful humanity by taking on himself the guilt and punishment for sin.

Activism describes the tendency toward active expression and sharing of the gospel in diverse ways that include preaching and social action. This aspect of evangelicalism continues to be seen today in the proliferation of evangelical voluntary religious groups and parachurch organizations.

Diversity

Together For the Gospel, an evangelical pastors' conference held biennially. A panel discussion with (from left to right) Albert Mohler, Ligon Duncan, C. J. Mahaney, and Mark Dever.

As a trans-denominational movement, evangelicalism occurs in nearly every Protestant denomination and tradition. The Reformed, Baptist, Wesleyan, Pentecostal, Churches of Christ, Plymouth Brethren, charismatic Protestant, and nondenominational Protestant traditions have all had strong influence within contemporary evangelicalism. Some Anabaptist denominations (such as the Brethren Church) are evangelical, and some Lutherans self-identify as evangelicals. There are also evangelical Anglicans.

In the early 20th century, evangelical influence declined within mainline Protestantism and Christian fundamentalism developed as a distinct religious movement. Between 1950 and 2000 a mainstream evangelical consensus developed that sought to be more inclusive and more culturally relevant than fundamentalism, while maintaining conservative Protestant teaching. According to Brian Stanley, professor of world Christianity, this new postwar consensus is termed neo-evangelicalism, the new evangelicalism, or simply evangelicalism in the United States, while in Great Britain and in other English-speaking countries, it is commonly termed conservative evangelicalism. Over the years, less-conservative evangelicals have challenged this mainstream consensus to varying degrees. Such movements have been classified by a variety of labels, such as progressive, open, post-conservative, and post-evangelical.

Christian fundamentalism

Fundamentalism (sometimes known as conservative evangelicalism) regards biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth of Jesus, penal substitutionary atonement, the literal resurrection of Christ, and the Second Coming of Christ as fundamental Christian doctrines. Fundamentalism arose among evangelicals in the 1920s to combat modernist or liberal theology in mainline Protestant churches. Failing to reform the mainline churches, fundamentalists separated from them and established their own churches, refusing to participate in ecumenical organizations such as the National Council of Churches (founded in 1950). They also made separatism (rigid separation from non-fundamentalist churches and their culture) a true test of faith. According to historian George Marsden, most fundamentalists are Baptists and dispensationalist.Mainstream varieties

The Prayer Book of 1662 included the Thirty-Nine Articles emphasized by evangelical Anglicans.

Mainstream evangelicalism is historically divided between two main orientations: confessionalism and revivalism. These two streams have been critical of each other. Confessional evangelicals have been suspicious of unguarded religious experience, while revivalist evangelicals have been critical of overly intellectual teaching that (they suspect) stifles vibrant spirituality. In an effort to broaden their appeal, many contemporary evangelical congregations intentionally avoid identifying with any single form of evangelicalism. These "generic evangelicals" are usually theologically and socially conservative, but their churches often present themselves as nondenominational within the broader evangelical movement.

In the words of Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, confessional evangelicalism refers to "that movement of Christian believers who seek a constant convictional continuity with the theological formulas of the Protestant Reformation". While approving of the evangelical distinctions proposed by Bebbington, confessional evangelicals believe that authentic evangelicalism requires more concrete definition in order to protect the movement from theological liberalism and from heresy. According to confessional evangelicals, subscription to the ecumenical creeds and to the Reformation-era confessions of faith (such as the confessions of the Reformed churches) provides such protection. Confessional evangelicals are represented by conservative Presbyterian churches (emphasizing the Westminster Confession), certain Baptist churches that emphasize historic Baptist confessions such as the Second London Confession, evangelical Anglicans who emphasize the Thirty-Nine Articles (such as in the Anglican Diocese of Sydney, Australia), and some confessional Lutherans with pietistic convictions.

The emphasis on historic Protestant orthodoxy among confessional evangelicals stands in direct contrast to an anti-creedal outlook that has exerted its own influence on evangelicalism, particularly among churches strongly affected by revivalism and by pietism. Revivalist evangelicals are represented by some quarters of Methodism, the Wesleyan Holiness churches, the Pentecostal/charismatic churches, some Anabaptist churches, and some Baptists and Presbyterians. Revivalist evangelicals tend to place greater emphasis on religious experience than their confessional counterparts.

Non-conservative varieties

Evangelicals dissatisfied with the movement's conservative mainstream have been variously described as progressive evangelicals, post-conservative evangelicals, Open Evangelicals and post-evangelicals. Progressive evangelicals, also known as the evangelical left, share theological or social views with other progressive Christians while also identifying with evangelicalism. Progressive evangelicals commonly advocate for women's equality, pacifism and social justice.As described by Baptist theologian Roger E. Olson, post-conservative evangelicalism is a theological school of thought that adheres to the four marks of evangelicalism, while being less rigid and more inclusive of other Christians. According to Olson, post-conservatives believe that doctrinal truth is secondary to spiritual experience shaped by Scripture. Post-conservative evangelicals seek greater dialogue with other Christian traditions and support the development of a multicultural evangelical theology that incorporates the voices of women, racial minorities, and Christians in the developing world. Some post-conservative evangelicals also support open theism and the possibility of near universal salvation.

The term "Open Evangelical" refers to a particular Christian school of thought or churchmanship, primarily in Great Britain (especially in the Church of England). Open evangelicals describe their position as combining a traditional evangelical emphasis on the nature of scriptural authority, the teaching of the ecumenical creeds and other traditional doctrinal teachings, with an approach towards culture and other theological points-of-view which tends to be more inclusive than that taken by other evangelicals. Some open evangelicals aim to take a middle position between conservative and charismatic evangelicals, while others would combine conservative theological emphases with more liberal social positions.

British author Dave Tomlinson coined the phrase post-evangelical to describe a movement comprising various trends of dissatisfaction among evangelicals. Others use the term with comparable intent, often to distinguish evangelicals in the so-called emerging church movement from post-evangelicals and anti-evangelicals. Tomlinson argues that "linguistically, the distinction [between evangelical and post-evangelical] resembles the one that sociologists make between the modern and postmodern eras".

History

Background

Count von Zinzendorf was a major influence on John Wesley in founding the Methodist movement.

Evangelicalism did not take recognizable form until the 18th century, first in Britain and its North American colonies. Nevertheless, there were earlier developments within the larger Protestant world that preceded and influenced the later evangelical revivals. According to religion scholar, social activist, and politician Randall Balmer, Evangelicalism resulted "from the confluence of Pietism, Presbyterianism, and the vestiges of Puritanism. Evangelicalism picked up the peculiar characteristics from each strain – warmhearted spirituality from the Pietists (for instance), doctrinal precisionism from the Presbyterians, and individualistic introspection from the Puritans". Historian Mark Noll adds to this list High Church Anglicanism, which contributed to Evangelicalism a legacy of "rigorous spirituality and innovative organization".

During the 17th century, Pietism emerged in Europe as a movement for the revival of piety and devotion within the Lutheran church. As a protest against "cold orthodoxy" or an overly formal and rational Christianity, Pietists advocated for an experiential religion that stressed high moral standards for both clergy and lay people. The movement included both Christians who remained in the liturgical, state churches as well as separatist groups who rejected the use of baptismal fonts, altars, pulpits, and confessionals. As Pietism spread, the movement's ideals and aspirations influenced and were absorbed into early Evangelicalism.

The Presbyterian heritage not only gave Evangelicalism a commitment to Protestant orthodoxy but also contributed a revival tradition that stretched back to the 1620s in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Central to this tradition was the communion season, which normally occurred in the summer months. For Presbyterians, celebrations of Holy Communion were infrequent but popular events preceded by several Sundays of preparatory preaching and accompanied with preaching, singing, and prayers.

Puritanism combined Calvinism with teaching that conversion was a prerequisite for church membership and a stress on the study of Scripture by lay people. It took root in New England, where the Congregational church was an established religion. The Half-Way Covenant of 1662 allowed parents who had not testified to a conversion experience to have their children baptized, while reserving Holy Communion for converted church members alone. By the 18th century, Puritanism was in decline and many ministers were alarmed at the loss of religious piety. This concern over declining religious commitment led many people to support evangelical revival.

High Church Anglicanism also exerted influence on early Evangelicalism. High Churchmen were distinguished by their desire to adhere to primitive Christianity. This desire included imitating the faith and ascetic practices of early Christians as well as regularly partaking of Holy Communion. High Churchmen were also enthusiastic organizers of voluntary religious societies. Two of the most prominent were the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, which distributed Bibles and other literature and built schools, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, which was created to facilitate missionary work in British colonies. Samuel and Susanna Wesley, the parents of John and Charles Wesley, were both devoted advocates of High Churchmanship.

18th century

Jonathan Edwards' account of the revival in Northampton was published in 1737 as A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton

In the 1730s, Evangelicalism emerged as a distinct phenomenon out of religious revivals that began in Britain and New England. While religious revivals had occurred within Protestant churches in the past, the evangelical revivals that marked the 18th century were more intense and radical. Evangelical revivalism imbued ordinary men and women with a confidence and enthusiasm for sharing the gospel and converting others outside of the control of established churches, a key discontinuity with the Protestantism of the previous era.

It was developments in the doctrine of assurance that differentiated Evangelicalism from what went before. Bebbington says, "The dynamism of the Evangelical movement was possible only because its adherents were assured in their faith." He goes on:

Whereas the Puritans had held that assurance is rare, late and the fruit of struggle in the experience of believers, the Evangelicals believed it to be general, normally given at conversion and the result of simple acceptance of the gift of God. The consequence of the altered form of the doctrine was a metamorphosis in the nature of popular Protestantism. There was a change in patterns of piety, affecting devotional and practical life in all its departments. The shift, in fact, was responsible for creating in Evangelicalism a new movement and not merely a variation on themes heard since the Reformation.The first local revival occurred in Northampton, Massachusetts, under the leadership of Congregationalist minister Jonathan Edwards. In the fall of 1734, Edwards preached a sermon series on "Justification By Faith Alone", and the community's response was extraordinary. Signs of religious commitment among the laity increased, especially among the town's young people. The revival ultimately spread to 25 communities in western Massachusetts and central Connecticut until it began to wane by the spring of 1735. Edwards was heavily influenced by Pietism, so much so that one historian has stressed his "American Pietism". One practice clearly copied from European Pietists was the use of small groups divided by age and gender, which met in private homes to conserve and promote the fruits of revival.

At the same time, students at Yale University (at that time Yale College) in New Haven, Connecticut, were also experiencing revival. Among them was Aaron Burr, Sr., who would become a prominent Presbyterian minister and future president of Princeton University. In New Jersey, Gilbert Tennent, another Presbyterian minister, was preaching the evangelical message and urging the Presbyterian Church to stress the necessity of converted ministers.

The spring of 1735 also marked important events in England and Wales. Howell Harris, a Welsh schoolteacher, had a conversion experience on May 25 during a communion service. He described receiving assurance of God's grace after a period of fasting, self-examination, and despair over his sins. Sometime later, Daniel Rowland, the Anglican curate of Llangeitho, Wales, experienced conversion as well. Both men began preaching the evangelical message to large audiences, becoming leaders of the Welsh Methodist revival. At about the same time that Harris experienced conversion in Wales, George Whitefield was converted at Oxford University after his own prolonged spiritual crisis. Whitefield later remarked, "About this time God was pleased to enlighten my soul, and bring me into the knowledge of His free grace, and the necessity of being justified in His sight by faith only".

When forbidden from preaching from the pulpits of parish churches, John Wesley began open-air preaching.

Whitefield's fellow Holy Club member and spiritual mentor, Charles Wesley, reported an evangelical conversion in 1738. In the same week, Charles' brother and future founder of Methodism, John Wesley was also converted after a long period of inward struggle. During this spiritual crisis, John Wesley was directly influenced by Pietism. Two years before his conversion, Wesley had traveled to the newly established colony of Georgia as a missionary for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. He shared his voyage with a group of Moravian Brethren led by August Gottlieb Spangenberg. The Moravians' faith and piety deeply impressed Wesley, especially their belief that it was a normal part of Christian life to have an assurance of one's salvation. Wesley recounted the following exchange with Spangenberg on February 7, 1736:

[Spangenberg] said, "My brother, I must first ask you one or two questions. Have you the witness within yourself? Does the Spirit of God bear witness with your spirit that you are a child of God?" I was surprised, and knew not what to answer. He observed it, and asked, "Do you know Jesus Christ?" I paused, and said, "I know he is the Savior of the world." "True," he replied, "but do you know he has saved you?" I answered, "I hope he has died to save me." He only added, "Do you know yourself?" I said, "I do." But I fear they were vain words.Wesley finally received the assurance he had been searching for at a meeting of a religious society in London. While listening to a reading from Martin Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans, Wesley felt spiritually transformed:

About a quarter before nine, while [the speaker] was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.Pietism continued to influence Wesley, who had translated 33 Pietist hymns from German to English. Numerous German Pietist hymns became part of the English Evangelical repertoire. By 1737, Whitefield had become a national celebrity in England where his preaching drew large crowds, especially in London where the Fetter Lane Society had become a center of evangelical activity. Whitfield joined forces with Edwards to "fan the flame of revival" in the Thirteen Colonies in 1739–40. Soon the First Great Awakening stirred Protestants throughout America.

Evangelical preachers emphasized personal salvation and piety more than ritual and tradition. Pamphlets and printed sermons crisscrossed the Atlantic, encouraging the revivalists. The Awakening resulted from powerful preaching that gave listeners a sense of deep personal revelation of their need of salvation by Jesus Christ. Pulling away from ritual and ceremony, the Great Awakening made Christianity intensely personal to the average person by fostering a deep sense of spiritual conviction and redemption, and by encouraging introspection and a commitment to a new standard of personal morality. It reached people who were already church members. It changed their rituals, their piety and their self-awareness. To the evangelical imperatives of Reformation Protestantism, 18th century American Christians added emphases on divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted within new believers an intense love for God. Revivals encapsulated those hallmarks and forwarded the newly created Evangelicalism into the early republic.

19th century

The start of the 19th century saw an increase in missionary work and many of the major missionary societies were founded around this time. Both the Evangelical and high church movements sponsored missionaries.The Second Great Awakening (which actually began in 1790) was primarily an American revivalist movement and resulted in substantial growth of the Methodist and Baptist churches. Charles Grandison Finney was an important preacher of this period.

William Wilberforce was a politician, philanthropist and an evangelical Anglican, who led the British movement to abolish the slave trade.

In Britain in addition to stressing the traditional Wesleyan combination of "Bible, cross, conversion, and activism", the revivalist movement sought a universal appeal, hoping to include rich and poor, urban and rural, and men and women. Special efforts were made to attract children and to generate literature to spread the revivalist message.

"Christian conscience" was used by the British Evangelical movement to promote social activism. Evangelicals believed activism in government and the social sphere was an essential method in reaching the goal of eliminating sin in a world drenched in wickedness. The Evangelicals in the Clapham Sect included figures such as William Wilberforce who successfully campaigned for the abolition of slavery.

In the late 19th century, the revivalist Holiness movement, based on the doctrine of "entire sanctification," took a more extreme form in rural America and Canada, where it ultimately broke away from institutional Methodism. In urban Britain the Holiness message was less exclusive and censorious.

John Nelson Darby of the Plymouth Brethren was a 19th-century Irish Anglican minister who devised modern dispensationalism, an innovative Protestant theological interpretation of the Bible that was incorporated in the development of modern Evangelicalism. Cyrus Scofield further promoted the influence of dispensationalism through the explanatory notes to his Scofield Reference Bible. According to scholar Mark S. Sweetnam, who takes a cultural studies perspective, dispensationalism can be defined in terms of its Evangelicalism, its insistence on the literal interpretation of Scripture, its recognition of stages in God's dealings with humanity, its expectation of the imminent return of Christ to rapture His saints, and its focus on both apocalypticism and premillennialism.

Notable figures of the latter half of the 19th century include Charles Spurgeon in London and Dwight L. Moody in Chicago. Their powerful preaching reached very large audiences.

An advanced theological perspective came from the Princeton theologians from the 1850s to the 1920s, such as Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander and B.B. Warfield.

20th century

Services at the Pentecostal Church of God in Lejunior, Kentucky, 1946

After 1910 the Fundamentalist movement dominated Evangelicalism in the early part of the 20th century; the Fundamentalists rejected liberal theology and emphasized the inerrancy of the Scriptures.

Following the 1904–1905 Welsh revival, the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 began the spread of Pentecostalism in North America.

In the post–World War II period a split developed between Evangelicals as they disagreed among themselves about how individual Christians ought to respond to an unbelieving world. Many Evangelicals urged that Christians must engage "the culture" directly and constructively, and they began to express reservations about being known to the world as fundamentalists. As Kenneth Kantzer put it at the time, the name fundamentalist had become "an embarrassment instead of a badge of honor".

The evangelical revivalist Billy Graham in Duisburg, Germany, 1954

In 1947 Harold Ockenga coined the term neo-evangelicalism to identify a distinct movement within self-identified fundamentalist Christianity at the time, especially in the English-speaking world. It described the mood of positivism and non-militancy that characterized that generation. The new generation of Evangelicals set as their goal to abandon a militant Bible stance. Instead, they would pursue dialogue, intellectualism, non-judgmentalism, and appeasement. They further called for an increased application of the gospel to sociological, political, and economic areas.

The self-identified fundamentalists also cooperated in separating their "neo-Evangelical" opponents from the fundamentalist name, by increasingly seeking to distinguish themselves from the more open group, whom they often characterized derogatorily by Ockenga's term, "neo-Evangelical" or just "Evangelical".

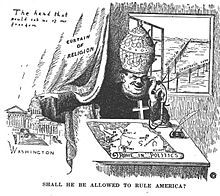

The fundamentalists saw the Evangelicals as often being too concerned about social acceptance and intellectual respectability, and being too accommodating to a perverse generation that needed correction. In addition, they saw the efforts of evangelist Billy Graham, who worked with non-Evangelical denominations, such as the Roman Catholics (whom fundamentalists saw as heretical), as a mistake.

The post-war period also saw growth of the ecumenical movement and the founding of the World Council of Churches, which the Evangelical community generally regarded with suspicion.

In the United Kingdom, John Stott (1921–2011) and Martyn Lloyd-Jones (1899–1981) emerged as key leaders in Evangelical Christianity.

The charismatic movement began in the 1960s and resulted in the introduction of Pentecostal theology and practice into many mainline denominations. New charismatic groups such as the Association of Vineyard Churches and Newfrontiers trace their roots to this period.

The closing years of the 20th century saw controversial postmodern influences entering some parts of Evangelicalism, particularly with the emerging church movement.

Global statistics

Universal Church of the Kingdom of God service in Russia.

According to a 2011 Pew Forum study on global Christianity, 285,480,000 or 13.1 percent of all Christians are Evangelicals. These figures do not include the Evangelical movements Pentecostalism and Charismatic movement; 584,080,000. The study states that the category "Evangelicals" should not be considered as a separate category of "Pentecostal and Charismatic" categories, since some believers consider themselves in both movements where their church is affiliated with an Evangelical association.

In 2015, the World Evangelical Alliance is "a network of churches in 129 nations that have each formed an Evangelical alliance and over 100 international organizations joining together to give a world-wide identity, voice, and platform to more than 600 million Evangelical Christians". The Alliance was formed in 1951 by Evangelicals from 21 countries. It has worked to support its members to work together globally.

According to Sébastien Fath of CNRS, in 2016, there are 619 million Evangelicals in the world, one in four Christians. In 2017, about 630 million, an increase of 11 million, including Pentecostals.

Operation World estimates the number of Evangelicals at 550 million. From 1960 to 2000, the global growth of the number of reported Evangelicals grew three times the world's population rate, and twice that of Islam.

Africa

In the 21st century, there are Evangelical churches active in Sudan, Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda, Ghana, Kenya, Zambia, South Africa, and Nigeria. They have grown especially since independence came in the 1960s, the strongest movements are based on Pentecostal-charismatic beliefs, and comprise a way of life that has led to upward social mobility and demands for democracy. There is a wide range of theology and organizations, including some sponsored by European missionaries and others that have emerged from African culture such as the Apostolic and Zionist Churches which enlist 40% of black South Africans, and their Aladura counterparts in western Africa.In Nigeria the Evangelical Church Winning All (formerly "Evangelical Church of West Africa") is the largest church organization with five thousand congregations and over three million members. It sponsors two seminaries and eight Bible colleges, and 1600 missionaries who serve in Nigeria and other countries with the Evangelical Missionary Society (EMS). There have been serious confrontations since 1999 between Muslims and Evangelical Christians standing in opposition to the expansion of Sharia law in northern Nigeria. The confrontation has radicalized and politicized the Christians. Violence has been escalating.

In Kenya, mainstream Evangelical denominations have taken the lead in promoting political activism and backers, with the smaller Evangelical sects of less importance. Daniel arap Moi was president 1978 to 2002 and claimed to be an Evangelical; he proved intolerant of dissent or pluralism or decentralization of power.

The Berlin Missionary Society (BMS) was one of four German Protestant mission societies active in South Africa before 1914. It emerged from the German tradition of Pietism after 1815 and sent its first missionaries to South Africa in 1834. There were few positive reports in the early years, but it was especially active 1859–1914. It was especially strong in the Boer republics. The World War cut off contact with Germany, but the missions continued at a reduced pace. After 1945 the missionaries had to deal with decolonisation across Africa and especially with the apartheid government. At all times the BMS emphasized spiritual inwardness, and values such as morality, hard work and self-discipline. It proved unable to speak and act decisively against injustice and racial discrimination and was disbanded in 1972.

Since 1974, young professionals have been the active proselytizers of Evangelicalism in the cities of Malawi.

In Mozambique, Evangelical Protestant Christianity emerged around 1900 from black migrants whose converted previously in South Africa. They were assisted by European missionaries, but, as industrial workers, they paid for their own churches and proselytizing. They prepared southern Mozambique for the spread of Evangelical Protestantism. During its time as a colonial power in Mozambique, the Catholic Portuguese government tried to counter the spread of Evangelical Protestantism.

East African Revival

The East African Revival was a renewal movement within Evangelical churches in East Africa during the late 1920s and 1930s that began at a Church Missionary Society mission station in the Belgian territory of Ruanda-Urundi in 1929, and spread to: Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya during the 1930s and 1940s contributing to the significant growth of the church in East Africa through the 1970s and had a visible influence on Western missionaries who were observer-participants of the movement.Latin America

In modern Latin America, the term "Evangelical" is often simply a synonym for "Protestant".Brazil

Temple of Solomon replica built by the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God in São Paulo

Protestantism in Brazil largely originated with German immigrants and British and American missionaries in the 19th century, following up on efforts that began in the 1820s.

In the late nineteenth century, while the vast majority of Brazilians were nominal Catholics, the nation was underserved by priests, and for large numbers their religion was only nominal. The Catholic Church in Brazil was de-established in 1890, and responded by increasing the number of dioceses and the efficiency of its clergy. Many Protestants came from a large German immigrant community, but they were seldom engaged in proselytism and grew mostly by natural increase.

Methodists were active along with Presbyterians and Baptists. The Scottish missionary Dr. Robert Reid Kalley, with support from the Free Church of Scotland, moved to Brazil in 1855, founding the first Evangelical church among the Portuguese-speaking population there in 1856. It was organized according to the Congregational policy as the Igreja Evangélica Fluminense; it became the mother church of Congregationalism in Brazil. The Seventh-day Adventists arrived in 1894, and the YMCA was organized in 1896. The missionaries promoted schools colleges and seminaries, including a liberal arts college in São Paulo, later known as Mackenzie, and an agricultural school in Lavras. The Presbyterian schools in particular later became the nucleus of the governmental system. In 1887 Protestants in Rio de Janeiro formed a hospital. The missionaries largely reached a working-class audience, as the Brazilian upper-class was wedded either to Catholicism or to secularism. By 1914, Protestant churches founded by American missionaries had 47,000 communicants, served by 282 missionaries. In general, these missionaries were more successful than they had been in Mexico, Argentina or elsewhere in Latin America.

Assemblies of God building in Brazil

There were 700,000 Protestants by 1930, and increasingly they were in charge of their own affairs. In 1930, the Methodist Church of Brazil became independent of the missionary societies and elected its own bishop. Protestants were largely from a working-class, but their religious networks help speed their upward social mobility.

Protestants accounted for fewer than 5% of the population until the 1960s, but grew exponentially by proselytizing and by 2000 made up over 15% of Brazilians affiliated with a church. Pentecostals and charismatic groups account for the vast majority of this expansion.

Pentecostal missionaries arrived early in the 20th century. Pentecostal conversions surged during the 1950s and 1960s, when native Brazilians began founding autonomous churches. The most influential included Brasil Para o Cristo (Brazil for Christ), founded in 1955 by Manoel de Mello. With an emphasis on personal salvation, on God's healing power, and on strict moral codes these groups have developed broad appeal, particularly among the booming urban migrant communities. In Brazil, since the mid-1990's, groups committed to uniting black identity, antiracism, and Evangelical theology have rapidly proliferated. Pentecostalism arrived in Brazil with Swedish and American missionaries in 1911. it grew rapidly, but endured numerous schisms and splits. In some areas the Evangelical Assemblies of God churches have taken a leadership role in politics since the 1960s. They claimed major credit for the election of Fernando Collor de Mello as president of Brazil in 1990.

According to the 2000 Census, 15.4% of the Brazilian population was Protestant. A recent research conducted by the Datafolha institute shows that 25% of Brazilians are Protestants, of which 19% are followers of Pentecostal denominations. The 2010 Census found out that 22.2% were Protestant at that date. Protestant denominations saw a rapid growth in their number of followers since the last decades of the 20th century. They are politically and socially conservative, and emphasize that God's favor translates into business success. The rich and the poor remained traditional Catholics, while most Evangelical Protestants were in the new lower-middle class–known as the "C class" (in a A–E classification system).

Chesnut argues that Pentecostalism has become "one of the principal organizations of the poor," for these churches provide the sort of social network that teach members the skills they need to thrive in a rapidly developing meritocratic society.

One large Evangelical church that originated from Brasil is the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), a neo‐Pentecostal denomination begun in 1977. It now has a presence in many countries, and claims millions of members worldwide.

Guatemala

Cash Luna, an evangelical Protestant televangelist in Guatemala

Protestants remained a small portion of the population until the late-twentieth century, when various Protestant groups experienced a demographic boom that coincided with the increasing violence of the Guatemalan Civil War. Two former Guatemalan heads of state, General Efraín Ríos Montt and Jorge Serrano Elías have been practicing Evangelical Protestants, as is Guatemala's current President, Jimmy Morales. General Montt, an Evangelical from the Pentecostal tradition, came to power through a coup. He escalated the war against leftist guerilla insurgents as a holy war against atheistic "forces of evil".

Asia

American pastor Johannes Maas preaching in Andhra Pradesh, India in 1974. Spreading the revival is an essential part of work done by evangelical missionaries.

South Korea

Protestant missionary activity in Asia was most successful in Korea. American Presbyterians and Methodists arrived in the 1880s and were well received. Between 1910 and 1945, when Korea was a Japanese colony, Christianity became in part an expression of nationalism in opposition to Japan's efforts to promote the Japanese language and the Shinto religion. In 1914, out of 16 million people, there were 86,000 Protestants and 79,000 Catholics; by 1934, the numbers were 168,000 and 147,000. Presbyterian missionaries were especially successful. Since the Korean War (1950–53), many Korean Christians have migrated to the U.S., while those who remained behind have risen sharply in social and economic status. Most Korean Protestant churches in the 21st century emphasize their Evangelical heritage. Korean Protestantism is characterized by theological conservatism coupled with an emotional revivalistic style. Most churches sponsor revival meetings once or twice a year. Missionary work is a high priority, with 13,000 men and women serving in missions across the world, putting Korea in second place just behind the US.Sukman argues that since 1945, Protestantism has been widely seen by Koreans as the religion of the middle class, youth, intellectuals, urbanites, and modernists. It has been a powerful force supporting South Korea's pursuit of modernity and emulation of the United States, and opposition to the old Japanese colonialism and to the authoritarianism of North Korea.

South Korea has been referred as an "evangelical superpower" for being the home to some of the largest and most dynamic Christian churches in the world; South Korea is also second to the U.S. in the number of missionaries sent abroad.

According to 2015 South Korean census, 9.7 million or 19.7% of the population described themselves as Protestants, many of whom belong to Presbyterian churches shaped by Evangelicalism.

Philippines

According to the 2010 census, 2.68% of Filipinos are Evangelicals. However, this figure has risen to 14% as of 2017. The Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches (PCEC), an organization of more than seventy Evangelical and Mainline Protestant churches, and more than 210 para-church organizations in the Philippines, counts more than 11 million members as of 2011.Great Britain

John Wesley (1703–1791) was an Anglican cleric and theologian who, with his brother Charles Wesley (1707–1788) and fellow cleric George Whitefield (1714 – 1770), founded Methodism. After 1791 the movement became independent of the Anglican Church as the "Methodist Connection". It became a force in its own right, especially among the working class.The Clapham Sect was a group of Church of England evangelicals and social reformers based in Clapham, London; they were active 1780s–1840s). John Newton (1725–1807) was the founder. They are described by the historian Stephen Tomkins as "a network of friends and families in England, with William Wilberforce as its centre of gravity, who were powerfully bound together by their shared moral and spiritual values, by their religious mission and social activism, by their love for each other, and by marriage".

Evangelicalism was a major force in the Anglican Church from about 1800 to the 1860s. By 1848 when an evangelical John Bird Sumner became Archbishop of Canterbury, between a quarter and a third of all Anglican clergy were linked to the movement, which by then had diversified greatly in its goals and they were no longer considered an organized faction.

In the 21st century there are an estimated 2 million Evangelicals in the UK. According to research performed by the Evangelical Alliance in 2013, 87% of UK evangelicals attend Sunday morning church services every week and 63% attend weekly or fortnightly small groups. An earlier survey conducted in 2012 found that 92% of evangelicals agree it is a Christian's duty to help those in poverty and 45% attend a church which has a fund or scheme that helps people in immediate need, and 42% go to a church that supports or runs a foodbank. 63% believe in tithing, and so give around 10% of their income to their church, Christian organisations and various charities 83% of UK evangelicals believe that the Bible has supreme authority in guiding their beliefs, views and behaviour and 52% read or listen to the Bible daily. The Evangelical Alliance, formed in 1846, was the first ecumenical evangelical body in the world and works to unite evangelicals, helping them listen to, and be heard by, the government, media and society.

United States

The Call rally in 2008, Washington, D.C.. United States Capitol in the background.

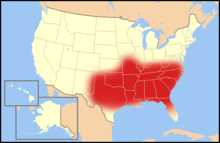

Socially conservative evangelical Protestantism plays a major role in the Bible Belt, an area covering almost all of the Southern United States. Evangelicals form a majority in the region.

By the late 19th to early 20th century, most American Protestants were Evangelicals. A divide had arisen between the more liberal-modernist mainline denominations and the fundamentalist denominations, the latter typically consisting of Evangelicals.

During and after World War II, Evangelicals became increasingly organized. There was a great expansion of Evangelical activity within the United States, "a revival of revivalism." Youth for Christ was formed; it later became the base for Billy Graham's revivals. The National Association of Evangelicals formed in 1942 as a counterpoise to the mainline Federal Council of Churches. In 1942–43, the Old-Fashioned Revival Hour had a record-setting national radio audience.

According to a Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life study, Evangelicals can be broadly divided into three camps: traditionalist, centrist, and modernist. A 2004 Pew survey identified Evangelicals as 26.3 percent of the population, while Catholics make up 22 percent and mainline Protestants make up 16 percent.

Evangelicals have been socially active throughout US history, a tradition dating back to the abolitionist movement of the Antebellum period and the prohibition movement. As a group, evangelicals are most often associated with the Christian right. However, a large number of black self-labeled Evangelicals, and a small proportion of liberal white self-labeled Evangelicals, gravitate towards the Christian left.

Recurrent themes within American Evangelical discourse include abortion, the creation–evolution controversy, secularism, and the notion of the United States as a Christian nation.