A perovskite solar cell is a type of solar cell which includes a perovskite structured compound, most commonly a hybrid organic-inorganic lead or tin halide-based material, as the light-harvesting active layer. Perovskite materials such as methylammonium lead halides and all-inorganic cesium lead halide, are cheap to produce and simple to manufacture.

Solar cell efficiencies of devices using these materials have increased from 3.8% in 2009 to 23.3% in late 2018 in single-junction architectures, and, in silicon-based tandem cells 27.3% exceeding the maximum efficiency achieved in single-junction silicon solar cells. Perovskite solar cells are therefore the fastest-advancing solar technology to date. With the potential of achieving even higher efficiencies and the very low production costs, perovskite solar cells have become commercially attractive, with start-up companies already promising modules and powerbanks on the market by 2017.

Solar cell efficiencies of devices using these materials have increased from 3.8% in 2009 to 23.3% in late 2018 in single-junction architectures, and, in silicon-based tandem cells 27.3% exceeding the maximum efficiency achieved in single-junction silicon solar cells. Perovskite solar cells are therefore the fastest-advancing solar technology to date. With the potential of achieving even higher efficiencies and the very low production costs, perovskite solar cells have become commercially attractive, with start-up companies already promising modules and powerbanks on the market by 2017.

Advantages

Metal

halide perovskites possess unique features that make them exciting for

solar cell applications. The raw materials used, and the possible

fabrication methods (such as various printing techniques) are both low

cost. Their high absorption coefficient enables ultrathin films of around 500 nm to absorb the complete visible solar spectrum.

These features combined result in the possibility to create low cost,

high efficiency, thin, lightweight and flexible solar modules.

Materials

Crystal structure of CH3NH3PbX3 perovskites (X=I, Br and/or Cl). The methylammonium cation (CH3NH3+) is surrounded by PbX6 octahedra.

The name 'perovskite solar cell' is derived from the ABX3 crystal structure of the absorber materials, which is referred to as perovskite structure. The most commonly studied perovskite absorber is methylammonium lead trihalide (CH3NH3PbX3, where X is a halogen atom such as iodine, bromine or chlorine), with an optical bandgap between 1.5 and 2.3 eV depending on halide content. Formamidinum lead trihalide (H2NCHNH2PbX3) has also shown promise, with bandgaps between 1.5 and 2.2 eV. The minimum bandgap is closer to the optimal for a single-junction cell than methylammonium lead trihalide, so it should be capable of higher efficiencies. The first use of perovskite in a solid state solar cell was in a dye-sensitized cell using CsSnI3 as a p-type hole transport layer and absorber.

A common concern is the inclusion of lead as a component of the perovskite materials; solar cells based on tin-based perovskite absorbers such as CH3NH3SnI3 have also been reported with lower power-conversion efficiencies.

In another recent development, solar cells based on transition

metal oxide perovskites and heterostructures thereof such as LaVO3/SrTiO3 are studied.

Rice University scientists have discovered a novel phenomenon of light-induced lattice expansion in perovskite materials.

In order to overcome the instability issues with lead-based

organic perovskite materials in ambient air and reduce the use of lead,

perovskite derivatives, such as Cs2SnI6 double perovskite, have also been investigated.

Processing

Perovskite solar cells hold an advantage over traditional silicon solar cells

in the simplicity of their processing. Traditional silicon cells

require expensive, multistep processes, conducted at high temperatures

(>1000 °C) in a high vacuum in special clean room facilities.

Meanwhile, the organic-inorganic perovskite material can be

manufactured with simpler wet chemistry techniques in a traditional lab

environment. Most notably, methylammonium and formamidinium lead

trihalides have been created using a variety of solvent techniques and

vapor deposition techniques, both of which have the potential to be

scaled up with relative feasibility.

In one-step solution processing, a lead halide and a methylammonium halide can be dissolved in a solvent and spin coated

onto a substrate. Subsequent evaporation and convective self-assembly

during spinning results in dense layers of well crystallized perovskite

material, due to the strong ionic interactions within the material (The

organic component also contributes to a lower crystallization

temperature). However, simple spin-coating does not yield homogenous

layers, instead requiring the addition of other chemicals such as GBL, DMSO, and toluene drips.

Simple solution processing results in the presence of voids, platelets,

and other defects in the layer, which would hinder the efficiency of a

solar cell.

Recently, a new approach for forming the PbI2 nanostructure and the use of high CH3NH3I

concentration have been adopted to form high quality (large crystal

size and smooth) perovskite film with better photovoltaic performances.

On one hand, self-assembled porous PbI2 is formed by incorporating small amounts of rationally chosen additives into the PbI2 precursor solutions, which significantly facilitate the conversion of perovskite without any PbI2 residue. On the other hand, through employing a relatively high CH3NH3I concentration, a firmly crystallized and uniform CH3NH3PbI3 film is formed.

Another technique using room temperature solvent-solvent

extraction produces high-quality crystalline films with precise control

over thickness down to 20 nanometers across areas several centimeters

square without generating pinholes. In this method "perovskite

precursors are dissolved in a solvent called NMP and coated onto a

substrate. Then, instead of heating, the substrate is bathed in diethyl ether,

a second solvent that selectively grabs the NMP solvent and whisks it

away. What's left is an ultra-smooth film of perovskite crystals."

In another solution processed method, the mixture of lead iodide

and methylammonium halide dissolved in DMF is preheated. Then the

mixture is spin coated on a substrate maintained at higher temperature.

This method produces uniform films of up to 1 mm grain size.

In vapor assisted techniques, spin coated or exfoliated lead

halide is annealed in the presence of methylammonium iodide vapor at a

temperature of around 150 °C.

This technique holds an advantage over solution processing, as it opens

up the possibility for multi-stacked thin films over larger areas. This could be applicable for the production of multi-junction cells.

Additionally, vapor deposited techniques result in less thickness

variation than simple solution processed layers. However, both

techniques can result in planar thin film layers or for use in

mesoscopic designs, such as coatings on a metal oxide scaffold. Such a

design is common for current perovskite or dye-sensitized solar cells.

Both processes hold promise in terms of scalability. Process cost

and complexity is significantly less than that of silicon solar cells.

Vapor deposition or vapor assisted techniques reduce the need for use of

further solvents, which reduces the risk of solvent remnants. Solution

processing is cheaper. Current issues with perovskite solar cells

revolve around stability, as the material is observed to degrade in

standard environmental conditions, suffering drops in efficiency.

In 2014, Olga Malinkiewicz presented her inkjet printing manufacturing process for perovskite sheets in Boston (US) during the MRS fall meeting – for which she received MIT Technology review's innovators under 35 award. The University of Toronto also claims to have developed a low-cost Inkjet solar cell in which the perovskite raw materials are blended into a Nanosolar ‘ink’ which can be applied by an inkjet printer onto glass, plastic or other substrate materials.

Physics

An important characteristic of the most commonly used perovskite system, the methylammonium lead halides, is a bandgap controllable by the halide content.

The materials also display a diffusion length for both holes and electrons of over one micron.

The long diffusion length means that these materials can function

effectively in a thin-film architecture, and that charges can be

transported in the perovskite itself over long distances.

It has recently been reported that charges in the perovskite material

are predominantly present as free electrons and holes, rather than as

bound excitons, since the exciton binding energy is low enough to enable charge separation at room temperature.

Efficiency limits

Perovskite

solar cell bandgaps are tunable and can be optimised for the solar

spectrum by altering the halide content in the film (i.e., by mixing I

and Br). The Shockley–Queisser limit radiative efficiency limit, also known as the detailed balance limit, is about 31% under an AM1.5G solar spectrum at 1000W/m2, for a Perovskite bandgap of 1.55 eV.

This is slightly smaller than the radiative limit of gallium arsenide

of bandgap 1.42 eV which can reach a radiative efficiency of 33%.

Values of the detailed balance limit are available in tabulated form and a MATLAB program for implementing the detailed balance model has been written.

In the meantime, the drift-diffusion model has found to

successfully predict the efficiency limit of perovskite solar cells,

which enable us to understand the device physics in-depth, especially

the radiative recombination limit and selective contact on device

performance. There are two prerequisites for predicting and approaching the perovskite efficiency limit. First, the intrinsic radiative recombination

needs to be corrected after adopting optical designs which will

significantly affect the open-circuit voltage at its Shockley–Queisser

limit. Second, the contact characteristics of the electrodes need

to be carefully engineered to eliminate the charge accumulation and

surface recombination at the electrodes. With the two procedures, the

accurate prediction of efficiency limit and precise evaluation of

efficiency degradation for perovskite solar cells are attainable by the

drift-diffusion model.

Along with analytical calculations, there have been many first

principle studies to find the characteristics of the perovskite material

numerically. These include but are not limited to bandgap, effective

mass, and defect levels for different perovskite materials. Also there have some efforts to cast light on the device mechanism based on simulations where Agrawal et al. suggests a modeling framework, presents analysis of near ideal efficiency, and talks about the importance of interface of perovskite and hole/electron transport layers. However, Sun et al. tries to come up with a compact model for perovskite different structures based on experimental transport data.

Architectures

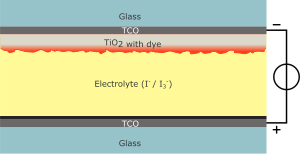

Schematic of a sensitized perovskite solar cell in which the active layer consist of a layer of mesoporous TiO2

which is coated with the perovskite absorber. The active layer is

contacted with an n-type material for electron extraction and a p-type

material for hole extraction. b) Schematic of a thin-film

perovskite solar cell. In this architecture in which just a flat layer

of perovskite is sandwiched between two selective contacts. c) Charge

generation and extraction in the sensitized architecture. After light

absorption in the perovskite absorber the photogenerated electron is

injected into the mesoporous TiO2 through which it is

extracted. The concomitantly generated hole is transferred to the p-type

material. d) Charge generation and extraction in the thin-film

architecture. After light absorption both charge generation as well as

charge extraction occurs in the perovskite layer.

Perovskite solar cells function efficiently in a number of somewhat

different architectures depending either on the role of the perovskite

material in the device, or the nature of the top and bottom electrode.

Devices in which positive charges are extracted by the transparent

bottom electrode (cathode), can predominantly be divided into

'sensitized', where the perovskite functions mainly as a light absorber,

and charge transport occurs in other materials, or 'thin-film', where

most electron or hole transport occurs in the bulk of the perovskite

itself. Similar to the sensitization in dye-sensitized solar cells, the perovskite material is coated onto a charge-conducting mesoporous scaffold – most commonly TiO2 – as light-absorber. The photogenerated

electrons are transferred from the perovskite layer to the mesoporous

sensitized layer through which they are transported to the electrode and

extracted into the circuit.

The thin film solar cell architecture is based on the finding that perovskite materials can also act as highly efficient, ambipolar charge-conductor.

After light absorption and the subsequent charge-generation, both

negative and positive charge carrier are transported through the

perovskite to charge selective contacts. Perovskite solar cells emerged

from the field of dye-sensitized solar cells, so the sensitized

architecture was that initially used, but over time it has become

apparent that they function well, if not ultimately better, in a

thin-film architecture.

More recently, some researchers also successfully demonstrated the

possibility of fabricating flexible devices with perovskites,

which makes it more promising for flexible energy demand. Certainly,

the aspect of UV-induced degradation in the sensitized architecture may

be detrimental for the important aspect of long-term stability.

There is another different class of architectures, in which the

transparent electrode at the bottom acts as cathode by collecting the

photogenerated p-type charge carriers.

History

These

perovskite materials have been well known for many years, but the first

incorporation into a solar cell was reported by Miyasaka et al. in 2009.

This was based on a dye-sensitized solar cell architecture, and generated only 3.8% power conversion efficiency (PCE) with a thin layer of perovskite on mesoporous TiO2

as electron-collector. Moreover, because a liquid corrosive electrolyte

was used, the cell was only stable for a matter of minutes. Park et al.

improved upon this in 2011, using the same dye-sensitized concept,

achieving 6.5% PCE.

A breakthrough came in 2012, when Henry Snaith and Mike Lee from the University of Oxford

realised that the perovskite was stable if contacted with a solid-state

hole transporter such as spiro-OMeTAD and did not require the

mesoporous TiO2 layer in order to transport electrons.

They showed that efficiencies of almost 10% were achievable using the 'sensitized' TiO2

architecture with the solid-state hole transporter, but higher

efficiencies, above 10%, were attained by replacing it with an inert

scaffold.

Further experiments in replacing the mesoporous TiO2 with Al2O3 resulted in increased open-circuit voltage and a relative improvement in efficiency of 3–5% more than those with TiO2 scaffolds.

This led to the hypothesis that a scaffold is not needed for electron

extraction, which was later proved correct. This realisation was then

closely followed by a demonstration that the perovskite itself could

also transport holes, as well as electrons.

A thin-film perovskite solar cell, with no mesoporous scaffold, of > 10% efficiency was achieved.

In 2013 both the planar and sensitized architectures saw a number

of developments.

Burschka et al. demonstrated a deposition technique for the sensitized

architecture exceeding 15% efficiency by a two-step solution processing, At a similar time Olga Malinkiewicz

et al, and Liu et al. showed that it was possible to fabricate planar

solar cells by thermal co-evaporation, achieving more than 12% and 15%

efficiency in a p-i-n and an n-i-p architecture respectively.

Docampo et al. also showed that it was possible to fabricate perovskite

solar cells in the typical 'organic solar cell' architecture, an

'inverted' configuration with the hole transporter below and the

electron collector above the perovskite planar film.

A range of new deposition techniques and even higher efficiencies

were reported in 2014. A reverse-scan efficiency of 19.3% was claimed

by Yang Yang at UCLA using the planar thin-film architecture. In November 2014, a device by researchers from KRICT achieved a record with the certification of a non-stabilized efficiency of 20.1%.

In December 2015, a new record efficiency of 21.0% was achieved by researchers at EPFL.

As of March 2016, researchers from KRICT and UNIST hold the highest certified record for a single-junction perovskite solar cell with 22.1%.

In 2018, a new record was set by researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences with a certified efficiency of 23.3%.

Stability

One

big challenge for perovskite solar cells (PSCs) is the aspect of

short-term and long-term stability. The instability of PSCs is mainly

related to environmental influence (moisture and oxygen), thermal influence (intrinsic stability), heating under applied voltage, photo influence (Ultraviolet light) (Visible light) and mechanical fragility.

Several studies about PSCs stability have been performed and some

elements have been proven to be important to the PSCs stability. However, there is no standard "operational" stability protocol for PSCs. But a method to quantify the intrinsic chemical stability of hybrid halide perovskites has been recently proposed.

The water-solubility of the organic constituent of the absorber

material make devices highly prone to rapid degradation in moist

environments.

The degradation which is caused by moisture can be reduced by

optimizing the constituent materials, the architecture of the cell, the

interfaces and the environment conditions during the fabrication steps. Encapsulating the perovskite absorber with a composite of carbon nanotubes

and an inert polymer matrix has been demonstrated to successfully

prevent the immediate degradation of the material when exposed to moist

ambient air at elevated temperatures.

However, no long term studies and comprehensive encapsulation

techniques have yet been demonstrated for perovskite solar cells.

Besides moisture instability, it has also been shown that the embodiment

of devices in which a mesoporous TiO2 layer is sensitized with the perovskite absorber exhibits UV light induced instability.

The cause for the observed decline in device performance of those solar

cells is linked to the interaction between photogenerated holes inside

the TiO2 and oxygen radicals on the surface of TiO2.

The measured ultra low thermal conductivity of 0.5 W/(Km) at room temperature in CH3NH3PbI3

can prevent fast propagation of the light deposited heat, and keep the

cell resistive on thermal stresses that can reduce its life time. The PbI2

residue in perovskite film has been experimentally demonstrated to have

a negative effect on the long-term stability of devices.

The stabilization problem is claimed to be solved by replacing the

organic transport layer with a metal oxide layer, allowing the cell to

retain 90% capacity after 60 days.

Besides, the two instabilities issues can be solved by using

multifunctional fluorinated photopolymer coatings that confer

luminescent and easy-cleaning features on the front side of the devices,

while concurrently forming a strongly hydrophobic barrier toward

environmental moisture on the back contact side.

The front coating can prevent the UV light of the whole incident solar

spectrum from negatively interacting with the PSC stack by converting it

into visible light, and the back layer can prevent water from

permeation within the solar cell stack. The resulting devices

demonstrated excellent stability in terms of power conversion

efficiencies during a 180-day aging test in the lab and a real outdoor

condition test for more than 3 months.

In July 2015 major hurdles were that the largest perovskite solar

cell was only the size of a fingernail and that they degraded quickly

in moist environments. However, researchers from EPFL

published in June 2017, a work successfully demonstrating large scale

perovskite solar modules with no observed degradation over one year.

Now, together with other organizations, the research team aims to

develop a fully printable perovskite solar cell with 22% efficiency and

with 90% of performance after ageing tests.

Apart from the moisture and oxygen, UV light is a critical

problem. The UV light will cause the perovskite layer CH3NH3PbI3 to

decompose and dramatically decrease the efficiency of the solar cell.

The basic idea to address this problem is to block the UV light when we

absorb the sun light. The more effective method is to aid another layer

on the solar layer, which is YVO4:EU3+ material. This material has a

very unique band gap which can block the UV light and let other light

goes through. By using this material, the efficiency of the solar will

be higher than 50% even after it is exposed to the sunlight for a very

long time. Advancements in the engineering of interfaces allowed the

creation of a 2D / 3D mixed perovskite, which enabled the creation of a

solar cell with over 10000 hour (more than 1 year) stable performance

without any loss in efficiency, pointing towards the viability of

commercialization.

The intrinsic fragility of the perovskite material requires extrinsic

reinforcement to shield this crucial layer from mechanical stresses.

Insertion of mechanically reinforcing scaffolds directly into the active

layers of perovskite solar cells resulted in the compound solar cell

formed exhibiting a 30-fold increase in fracture resistance,

repositioning the fracture properties of perovskite solar cells into the

same domain as conventional c-Si, CIGS and CdTe solar cells.

Hysteretic current-voltage behavior

Another

major challenge for perovskite solar cells is the observation that

current-voltage scans yield ambiguous efficiency values.

The power-conversion efficiency of a solar cell is usually determined by characterizing its current-voltage (IV) behavior

under simulated solar illumination. In contrast to other solar cells,

however, it has been observed that the IV-curves of perovskite solar

cells show a hysteretic

behavior: depending on scanning conditions – such as scan direction,

scan speed, light soaking, biasing – there is a discrepancy between the

scan from forward-bias to short-circuit (FB-SC) and the scan from

short-circuit to forward bias (SC-FB). Various causes have been proposed such as ion movement, polarization, ferroelectric effects, filling of trap states,

however, the exact origin for the hysteretic behavior is yet to be

determined. But it appears that determining the solar cell efficiency

from IV-curves risks producing inflated values if the scanning

parameters exceed the time-scale which the perovskite system requires in

order to reach an electronic steady-state.

Two possible solutions have been proposed: Unger et al. show that

extremely slow voltage-scans allow the system to settle into

steady-state conditions at every measurement point which thus eliminates

any discrepancy between the FB-SC and the SC-FB scan. Henry Snaith

et al. have proposed 'stabilized power output' as a metric for the

efficiency of a solar cell. This value is determined by holding the

tested device at a constant voltage around the maximum power-point

(where the product of voltage and photocurrent reaches its maximum

value) and track the power-output until it reaches a constant value.

Both methods have been demonstrated to yield lower efficiency values

when compared to efficiencies determined by fast IV-scans.

However, initial studies have been published that show that surface

passivation of the perovskite absorber is an avenue with which

efficiency values can be stabilized very close to fast-scan

efficiencies.

Initial reports suggest that in the 'inverted architecture', which has a

transparent cathode, little to no hysteresis is observed.

This suggests that the interfaces might play a crucial role with

regards to the hysteretic IV behavior since the major difference of the

inverted architecture to the regular architectures is that an organic

n-type contact is used instead of a metal oxide.

The observation of hysteretic current-voltage characteristics has

thus far been largely underreported. Only a small fraction of

publications acknowledge the hysteretic behavior of the described

devices, even fewer articles show slow non-hysteretic IV curves or

stabilized power outputs. Reported efficiencies, based on rapid

IV-scans, have to be considered fairly unreliable and make it currently

difficult to genuinely assess the progress of the field.

The ambiguity in determining the solar cell efficiency from

current-voltage characteristics due to the observed hysteresis has also

affected the certification process done by accredited laboratories such

as NREL.

The record efficiency of 20.1% for perovskite solar cells accepted as

certified value by NREL in November 2014, has been classified as 'not

stabilized'.

To be able to compare results from different institution, it is

necessary to agree on a reliable measurement protocol, as it has been

proposed by including the corresponding Matlab code which can be found at GitHub.

Perovskites for tandem applications

A

perovskite cell combined with bottom cell such as Si or copper indium

gallium selenide (CIGS) as a tandem design can suppress individual cell

bottlenecks and take advantage of the complementary characteristics to

enhance the efficiency.

This type of cells have higher efficiency potential, and therefore

attracted recently a large attention from academic researchers.

4-terminal tandems

Using a four terminal configuration in which the two sub-cells are electrically isolated, Bailie et al.

obtained a 17% and 18.6% efficient tandem cell with mc-Si (η ~ 11%) and

copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS, η ~ 17%) bottom cells,

respectively. A 13.4% efficient tandem cell with a highly efficient

a-Si:H/c-Si heterojunction bottom cell using the same configuration was

obtained.

The application of TCO-based transparent electrodes to perovskite cells

allowed to fabricate near-infrared transparent devices with improved

efficiency and lower parasitic absorption losses. The application of these cells in 4-terminal tandems allowed improved efficiencies up to 26.7% when using a silicon bottom cell and up to 23.9% with a CIGS bottom cell.

2-terminal tandems

Mailoa

et al. started the efficiency race for monolithic 2-terminal tandems

using an homojunction c-Si bottom cell and demonstrate a 13.7% cell,

largely limited by parasitic absorption losses. Then, Albrecht et al. developed a low-temperature processed perovskite cells using a SnO2

electron transport layer. This allowed the use of silicon

heterojunction solar cells as bottom cell and tandem efficiencies up to

18.1%. Werner et al. then improved this performance replacing the SnO2

layer with PCBM and introducing a sequential hybrid deposition method

for the perovskite absorber, leading to a tandem cell with 21.2%

efficiency.

Important parasitic absorption losses due to the use of Spiro-OMeTAD

were still limiting the overall performance. An important change was

demonstrated by Bush et al., who inverted the polarity of the top cell

(n-i-p to p-i-n). They used a bilayer of SnO2 and zinc tin

oxide (ZTO) processed by ALD to work as a sputtering buffer layer, which

enables the following deposition of a transparent top indium tin oxide

(ITO) electrode. This change helped to improve the environmental and

thermal stability of the perovskite cell and was crucial to further improve the perovskite/silicon tandem performance to 23.6% In the continuity, using a p-i-n perovskite top cell, Sahli et al.

demonstrated in June 2018 a fully textured monolithic tandem cell with

25.2% efficiency, independently certified by Fraunhofer ISE CalLab.

This improved efficiency can largely be attributed to the massively

reduced reflection losses (below 2% in the range 360 nm-1000 nm,

excluding metallization) and reduced parasitic absorption losses,

leading to certified short-circuit currents of 19.5mA/cm2. Also in June 2018 the company Oxford Photovoltaics presented a cell with 27.3% efficiency.

Theoretical modelling

There

have been some efforts to predict the theoretical limits for these

traditional tandem designs using a perovskite cell as top cell on a c-Si or a-Si/c-Si heterojunction bottom cell.

To show that the output power can be even further enhanced, bifacial

structures were studied as well. It was concluded that extra output

power can be extracted from the bifacial structure as compared to a

bifacial HIT cell when the albedo reflection takes on values between 10

and 40%, which are realistic.

Up-scaling

In May 2016, IMEC

and its partner Solliance announced a tandem structure with a

semi-transparent perovskite cell stacked on top of a back-contacted

silicon cell. A combined power conversion efficiency of 20.2% was claimed, with the potential to exceed 30%.

All-perovskite tandems

In

2016, the development of efficient low-bandgap (1.2 - 1.3eV) perovskite

materials and the fabrication of efficient devices based on these

enabled a new concept: all-perovskite tandem solar cells, where two

perovskite compounds with different bandgaps are stacked on top of each

other. The first two- and four-terminal devices with this architecture

reported in the literature achieved efficiencies of 17% and 20.3%.

All-perovskite tandem cells offer the prospect of being the first fully

solution-processable architecture that has a clear route to exceeding

not only the efficiencies of silicon, but also GaAs and other expensive

III-V semiconductor solar cells.

In 2017, Dewei Zhao et al. fabricated low-bandgap (~1.25 eV)

mixed Sn-Pb perovskite solar cells (PVSCs) with the thickness of 620 nm,

which enables larger grains and higher crystallinity to extend the

carrier lifetimes to more than 250 ns, reaching a maximum power

conversion efficiency (PCE) of 17.6%. Furthermore, this low-bandgap PVSC

reached an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of more than 70% in the

wavelength range of 700–900 nm, the essential infrared spectral region

where sunlight transmitted to bottom cell. They also combined the bottom

cell with a ~1.58 eV bandgap perovskite top cell to create an

all-perovskite tandem solar cell with four terminals, obtaining a

steady-state PCE of 21.0%, suggesting the possibility of fabricating

high-efficiency all-perovskite tandem solar cells.

![{\displaystyle {\ce {S^{.}->[{} \atop {\ce {TiO2}}]{S+}+e-}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4a8461f7deace264f9b77a6e9f2d2a67e729f5fa)