Carl Friedrich Gauss

| |

|---|---|

Carl Friedrich Gauß (1777–1855), painted by Christian Albrecht Jensen

| |

| Born |

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss

30 April 1777 |

| Died | 23 February 1855 (aged 77) |

| Residence | Kingdom of Hanover |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Collegium Carolinum, University of Göttingen, University of Helmstedt |

| Known for | See full list |

| Awards | Lalande Prize (1809) Copley Medal (1838) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics and physics |

| Institutions | University of Göttingen |

| Thesis | Demonstratio nova... (1799) |

| Doctoral advisor | Johann Friedrich Pfaff |

| Other academic advisors | Johann Christian Martin Bartels |

| Doctoral students | Johann Listing Christian Ludwig Gerling Richard Dedekind Bernhard Riemann Christian Peters Moritz Cantor |

| Other notable students | Johann Encke Christoph Gudermann Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet Gotthold Eisenstein Carl Wolfgang Benjamin Goldschmidt Gustav Kirchhoff Ernst Kummer August Ferdinand Möbius L.C. Schnürlein Julius Weisbach Sophie Germain (epistolary correspondent) |

| Influenced | Ferdinand Minding |

| Signature | |

| |

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (/ɡaʊs/; German: Gauß [ˈkaɐ̯l ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈɡaʊs] Latin: Carolus Fridericus Gauss; (30 April 1777 – 23 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and sciences. Sometimes referred to as the Princeps mathematicorum (Latin for "the foremost of mathematicians") and "the greatest mathematician since antiquity", Gauss had an exceptional influence in many fields of mathematics and science, and is ranked among history's most influential mathematicians.

Personal life

Early years

Statue of Gauss at his birthplace, Brunswick

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss was born on 30 April 1777 in Brunswick (Braunschweig), in the Duchy of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (now part of Lower Saxony, Germany), to poor, working-class parents.

His mother was illiterate and never recorded the date of his birth,

remembering only that he had been born on a Wednesday, eight days before

the Feast of the Ascension (which occurs 39 days after Easter). Gauss later solved this puzzle about his birthdate in the context of finding the date of Easter, deriving methods to compute the date in both past and future years. He was christened and confirmed in a church near the school he attended as a child.

Gauss was a child prodigy. In his memorial on Gauss, Wolfgang Sartorius von Waltershausen

says that when Gauss was barely three years old he corrected a math

error his father made; and that when he was seven, he confidently solved

an arithmetic series problem faster than anyone else in his class of 100 students.

Many versions of this story have been retold since that time with

various details regarding what the series was – the most frequent being

the classical problem of adding all the integers from 1 to 100.

There are many other anecdotes about his precocity while a toddler, and

he made his first groundbreaking mathematical discoveries while still a

teenager. He completed his magnum opus, Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, in 1798, at the age of 21—though it was not published until 1801. This work was fundamental in consolidating number theory as a discipline and has shaped the field to the present day.

Gauss's intellectual abilities attracted the attention of the Duke of Brunswick, who sent him to the Collegium Carolinum (now Braunschweig University of Technology), which he attended from 1792 to 1795, and to the University of Göttingen from 1795 to 1798.

While at university, Gauss independently rediscovered several important theorems. His breakthrough occurred in 1796 when he showed that a regular polygon can be constructed by compass and straightedge if the number of its sides is the product of distinct Fermat primes and a power of 2.

This was a major discovery in an important field of mathematics;

construction problems had occupied mathematicians since the days of the Ancient Greeks, and the discovery ultimately led Gauss to choose mathematics instead of philology as a career.

Gauss was so pleased with this result that he requested that a regular heptadecagon be inscribed on his tombstone. The stonemason declined, stating that the difficult construction would essentially look like a circle.

The year 1796 was more productive for both Gauss and number

theory. He discovered a construction of the heptadecagon on 30 March. He further advanced modular arithmetic, greatly simplifying manipulations in number theory. On 8 April he became the first to prove the quadratic reciprocity

law. This remarkably general law allows mathematicians to determine the

solvability of any quadratic equation in modular arithmetic. The prime number theorem, conjectured on 31 May, gives a good understanding of how the prime numbers are distributed among the integers.

Gauss also discovered that every positive integer is representable as a sum of at most three triangular numbers on 10 July and then jotted down in his diary the note: "ΕΥΡΗΚΑ! num = Δ + Δ' + Δ". On 1 October he published a result on the number of solutions of polynomials with coefficients in finite fields, which 150 years later led to the Weil conjectures.

Later years and death

Gauss on his deathbed (1855)

Gauss's gravesite at Albani Cemetery in Göttingen, Germany

Gauss remained mentally active into his old age, even while suffering from gout and general unhappiness. For example, at the age of 62, he taught himself Russian.

In 1840, Gauss published his influential Dioptrische Untersuchungen, in which he gave the first systematic analysis on the formation of images under a paraxial approximation (Gaussian optics). Among his results, Gauss showed that under a paraxial approximation an optical system can be characterized by its cardinal points and he derived the Gaussian lens formula.

In 1845, he became an associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands; when that became the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1851, he joined as a foreign member.

In 1854, Gauss selected the topic for Bernhard Riemann's inaugural lecture "Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen" (About the hypotheses that underlie Geometry). On the way home from Riemann's lecture, Weber reported that Gauss was full of praise and excitement.

On 23 February 1855, Gauss died of a heart attack in Göttingen (then Kingdom of Hanover and now Lower Saxony); he is interred in the Albani Cemetery there. Two people gave eulogies at his funeral: Gauss's son-in-law Heinrich Ewald, and Wolfgang Sartorius von Waltershausen, who was Gauss's close friend and biographer. Gauss's brain was preserved and was studied by Rudolf Wagner, who found its mass to be slightly above average, at 1,492 grams, and the cerebral area equal to 219,588 square millimeters

(340.362 square inches). Highly developed convolutions were also found,

which in the early 20th century were suggested as the explanation of

his genius.

Religious views

Gauss was a Lutheran Protestant, a member of the St. Albans Evangelical Lutheran church in Göttingen.

Potential evidence that Gauss believed in God comes from his response

after solving a problem that had previously defeated him: "Finally, two

days ago, I succeeded—not on account of my hard efforts, but by the

grace of the Lord." One of his biographers, G. Waldo Dunnington, described Gauss's religious views as follows:

For him science was the means of exposing the immortal nucleus of the human soul. In the days of his full strength, it furnished him recreation and, by the prospects which it opened up to him, gave consolation. Toward the end of his life, it brought him confidence. Gauss's God was not a cold and distant figment of metaphysics, nor a distorted caricature of embittered theology. To man is not vouchsafed that fullness of knowledge which would warrant his arrogantly holding that his blurred vision is the full light and that there can be none other which might report the truth as does his. For Gauss, not he who mumbles his creed, but he who lives it, is accepted. He believed that a life worthily spent here on earth is the best, the only, preparation for heaven. Religion is not a question of literature, but of life. God's revelation is continuous, not contained in tablets of stone or sacred parchment. A book is inspired when it inspires. The unshakeable idea of personal continuance after death, the firm belief in a last regulator of things, in an eternal, just, omniscient, omnipotent God, formed the basis of his religious life, which harmonized completely with his scientific research.

Apart from his correspondence, there are not many known details about

Gauss's personal creed. Many biographers of Gauss disagree about his

religious stance, with Bühler and others considering him a deist with very unorthodox views,

while Dunnington (though admitting that Gauss did not believe literally

in all Christian dogmas and that it is unknown what he believed on most

doctrinal and confessional questions) points out that he was, at least,

a nominal Lutheran.

In connection to this, there is a record of a conversation between Rudolf Wagner and Gauss, in which they discussed William Whewell's book Of the Plurality of Worlds.

In this work, Whewell had discarded the possibility of existing life in

other planets, on the basis of theological arguments, but this was a

position with which both Wagner and Gauss disagreed. Later Wagner

explained that he did not fully believe in the Bible, though he

confessed that he "envied" those who were able to easily believe. This later led them to discuss the topic of faith, and in some other religious remarks, Gauss said that he had been more influenced by theologians like Lutheran minister Paul Gerhardt than by Moses. Other religious influences included Wilhelm Braubach, Johann Peter Süssmilch, and the New Testament.

Dunnington further elaborates on Gauss's religious views by writing:

Gauss's religious consciousness was based on an insatiable thirst for truth and a deep feeling of justice extending to intellectual as well as material goods. He conceived spiritual life in the whole universe as a great system of law penetrated by eternal truth, and from this source he gained the firm confidence that death does not end all.

Gauss declared he firmly believed in the afterlife, and saw spirituality as something essentially important for human beings. He was quoted stating: "The world would be nonsense, the whole creation an absurdity without immortality," and for this statement he was severely criticized by the atheist Eugen Dühring who judged him as a narrow superstitious man.

Though he was not a church-goer, Gauss strongly upheld religious tolerance,

believing "that one is not justified in disturbing anothers religious

belief, in which they find consolation for earthly sorrows in time of

trouble."

When his son Eugene announced that he wanted to become a Christian

missionary, Gauss approved of this, saying that regardless of the

problems within religious organizations, missionary work was "a highly

honorable" task.

Family

Gauss's daughter Therese (1816–1864)

On 9 October 1805, Gauss married Johanna Osthoff (1780–1809), and had a son and a daughter with her. Johanna died on 11 October 1809, and her most recent child, Louis, died the following year. Gauss plunged into a depression from which he never fully recovered. He then married Minna Waldeck (1788–1831) on 4 August 1810, and had three more children. Gauss was never quite the same without his first wife, and he, just like his father, grew to dominate his children. Minna Waldeck died on 12 September 1831.

Gauss had six children. With Johanna (1780–1809), his children

were Joseph (1806–1873), Wilhelmina (1808–1846) and Louis (1809–1810).

With Minna Waldeck he also had three children: Eugene (1811–1896),

Wilhelm (1813–1879) and Therese (1816–1864). Eugene shared a good

measure of Gauss's talent in languages and computation.

After his second wife's death in 1831 Therese took over the household

and cared for Gauss for the rest of his life. His mother lived in his

house from 1817 until her death in 1839.

Gauss eventually had conflicts with his sons. He did not want any

of his sons to enter mathematics or science for "fear of lowering the

family name", as he believed none of them would surpass his own

achievements.

Gauss wanted Eugene to become a lawyer, but Eugene wanted to study

languages. They had an argument over a party Eugene held, which Gauss

refused to pay for. The son left in anger and, in about 1832, emigrated

to the United States, where he was quite successful. While working for

the American Fur Company in the Midwest, he learned the Sioux language.

Later, he moved to Missouri

and became a successful businessman. Wilhelm also moved to America in

1837 and settled in Missouri, starting as a farmer and later becoming

wealthy in the shoe business in St. Louis. It took many years for Eugene's success to counteract his reputation among Gauss's friends and colleagues. See also the letter from Robert Gauss to Felix Klein on 3 September 1912.

Personality

Carl Gauss was an ardent perfectionist

and a hard worker. He was never a prolific writer, refusing to publish

work which he did not consider complete and above criticism. This was in

keeping with his personal motto pauca sed matura ("few, but

ripe"). His personal diaries indicate that he had made several important

mathematical discoveries years or decades before his contemporaries

published them. Scottish-American mathematician and writer Eric Temple Bell said that if Gauss had published all of his discoveries in a timely manner, he would have advanced mathematics by fifty years.

Though he did take in a few students, Gauss was known to dislike

teaching. It is said that he attended only a single scientific

conference, which was in Berlin in 1828. However, several of his students became influential mathematicians, among them Richard Dedekind and Bernhard Riemann.

On Gauss's recommendation, Friedrich Bessel was awarded an honorary doctor degree from Göttingen in March 1811. Around that time, the two men engaged in an epistolary correspondence. However, when they met in person in 1825, they quarreled; the details are unknown.

Before she died, Sophie Germain was recommended by Gauss to receive her honorary degree; she never received it.

Gauss usually declined to present the intuition behind his often

very elegant proofs—he preferred them to appear "out of thin air" and

erased all traces of how he discovered them. This is justified, if unsatisfactorily, by Gauss in his Disquisitiones Arithmeticae,

where he states that all analysis (i.e., the paths one traveled to

reach the solution of a problem) must be suppressed for sake of brevity.

Gauss supported the monarchy and opposed Napoleon, whom he saw as an outgrowth of revolution.

Gauss summarized his views on the pursuit of knowledge in a letter to Farkas Bolyai dated 2 September 1808 as follows:

It is not knowledge, but the act of learning, not possession but the act of getting there, which grants the greatest enjoyment. When I have clarified and exhausted a subject, then I turn away from it, in order to go into darkness again. The never-satisfied man is so strange; if he has completed a structure, then it is not in order to dwell in it peacefully, but in order to begin another. I imagine the world conqueror must feel thus, who, after one kingdom is scarcely conquered, stretches out his arms for others.

Career and achievements

Algebra

Title page of Gauss's magnum opus, Disquisitiones Arithmeticae

In his 1799 doctorate in absentia, A new proof of the theorem that

every integral rational algebraic function of one variable can be

resolved into real factors of the first or second degree, Gauss proved the fundamental theorem of algebra which states that every non-constant single-variable polynomial with complex coefficients has at least one complex root. Mathematicians including Jean le Rond d'Alembert

had produced false proofs before him, and Gauss's dissertation contains

a critique of d'Alembert's work. Ironically, by today's standard,

Gauss's own attempt is not acceptable, owing to the implicit use of the Jordan curve theorem.

However, he subsequently produced three other proofs, the last one in

1849 being generally rigorous. His attempts clarified the concept of

complex numbers considerably along the way.

Gauss also made important contributions to number theory with his 1801 book Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (Latin, Arithmetical Investigations), which, among other things, introduced the symbol ≡ for congruence and used it in a clean presentation of modular arithmetic, contained the first two proofs of the law of quadratic reciprocity, developed the theories of binary and ternary quadratic forms, stated the class number problem for them, and showed that a regular heptadecagon (17-sided polygon) can be constructed with straightedge and compass. It appears that Gauss already knew the

class number formula in 1801.

In addition, he proved the following conjectured theorems:

- Fermat polygonal number theorem for n = 3

- Fermat's last theorem for n = 5

- Descartes's rule of signs

- Kepler conjecture for regular arrangements

He also

- explained the pentagramma mirificum (see University of Bielefeld website)

- developed an algorithm for determining the date of Easter

- invented the Cooley–Tukey FFT algorithm for calculating the discrete Fourier transforms 160 years before Cooley and Tukey

Astronomy

Portrait of Gauss published in Astronomische Nachrichten (1828)

In the same year, Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered the dwarf planet Ceres.

Piazzi could only track Ceres for somewhat more than a month, following

it for three degrees across the night sky. Then it disappeared

temporarily behind the glare of the Sun. Several months later, when

Ceres should have reappeared, Piazzi could not locate it: the

mathematical tools of the time were not able to extrapolate a position

from such a scant amount of data—three degrees represent less than 1% of

the total orbit. Gauss heard about the problem and tackled it. After

three months of intense work, he predicted a position for Ceres in

December 1801—just about a year after its first sighting—and this turned

out to be accurate within a half-degree when it was rediscovered by Franz Xaver von Zach on 31 December at Gotha, and one day later by Heinrich Olbers in Bremen.

Gauss's method involved determining a conic section

in space, given one focus (the Sun) and the conic's intersection with

three given lines (lines of sight from the Earth, which is itself moving

on an ellipse, to the planet) and given the time it takes the planet to

traverse the arcs determined by these lines (from which the lengths of

the arcs can be calculated by Kepler's Second Law).

This problem leads to an equation of the eighth degree, of which one

solution, the Earth's orbit, is known. The solution sought is then

separated from the remaining six based on physical conditions. In this

work, Gauss used comprehensive approximation methods which he created

for that purpose.

One such method was the fast Fourier transform. While this method is traditionally attributed to a 1965 paper by J.W. Cooley and J.W. Tukey, Gauss developed it as a trigonometric interpolation method. His paper, Theoria Interpolationis Methodo Nova Tractata, was only published posthumously in Volume 3 of his collected works. This paper predates the first presentation by Joseph Fourier on the subject in 1807.

Zach noted that "without the intelligent work and calculations of

Doctor Gauss we might not have found Ceres again". Though Gauss had up

to that point been financially supported by his stipend from the Duke,

he doubted the security of this arrangement, and also did not believe

pure mathematics to be important enough to deserve support. Thus he

sought a position in astronomy, and in 1807 was appointed Professor of

Astronomy and Director of the astronomical observatory in Göttingen, a post he held for the remainder of his life.

The discovery of Ceres led Gauss to his work on a theory of the

motion of planetoids disturbed by large planets, eventually published in

1809 as Theoria motus corporum coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientum

(Theory of motion of the celestial bodies moving in conic sections

around the Sun). In the process, he so streamlined the cumbersome

mathematics of 18th-century orbital prediction that his work remains a

cornerstone of astronomical computation. It introduced the Gaussian gravitational constant, and contained an influential treatment of the method of least squares, a procedure used in all sciences to this day to minimize the impact of measurement error.

Gauss proved the method under the assumption of normally distributed errors. The method had been described earlier by Adrien-Marie Legendre in 1805, but Gauss claimed that he had been using it since 1794 or 1795.

In the history of statistics, this disagreement is called the "priority

dispute over the discovery of the method of least squares."

Geodetic survey

Geodetic survey stone in Garlste (now Garlstedt)

In 1818 Gauss, putting his calculation skills to practical use, carried out a geodetic survey of the Kingdom of Hanover, linking up with previous Danish surveys. To aid the survey, Gauss invented the heliotrope, an instrument that uses a mirror to reflect sunlight over great distances, to measure positions.

Non-Euclidean geometries

Gauss also claimed to have discovered the possibility of non-Euclidean geometries

but never published it. This discovery was a major paradigm shift in

mathematics, as it freed mathematicians from the mistaken belief that

Euclid's axioms were the only way to make geometry consistent and

non-contradictory.

Research on these geometries led to, among other things, Einstein's theory of general relativity, which describes the universe as non-Euclidean. His friend Farkas Wolfgang Bolyai

with whom Gauss had sworn "brotherhood and the banner of truth" as a

student, had tried in vain for many years to prove the parallel

postulate from Euclid's other axioms of geometry.

Bolyai's son, János Bolyai,

discovered non-Euclidean geometry in 1829; his work was published in

1832. After seeing it, Gauss wrote to Farkas Bolyai: "To praise it would

amount to praising myself. For the entire content of the work ...

coincides almost exactly with my own meditations which have occupied my

mind for the past thirty or thirty-five years."

This unproved statement put a strain on his relationship with Bolyai who thought that Gauss was "stealing" his idea.

Letters from Gauss years before 1829 reveal him obscurely discussing the problem of parallel lines. Waldo Dunnington, a biographer of Gauss, argues in Gauss, Titan of Science

that Gauss was in fact in full possession of non-Euclidean geometry

long before it was published by Bolyai, but that he refused to publish

any of it because of his fear of controversy.

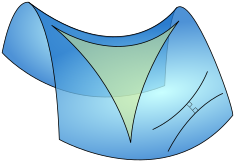

Theorema Egregium

The geodetic survey of Hanover, which required Gauss to spend summers traveling on horseback for a decade, fueled Gauss's interest in differential geometry and topology, fields of mathematics dealing with curves and surfaces. Among other things, he came up with the notion of Gaussian curvature.

This led in 1828 to an important theorem, the Theorema Egregium (remarkable theorem), establishing an important property of the notion of curvature. Informally, the theorem says that the curvature of a surface can be determined entirely by measuring angles and distances on the surface.

That is, curvature does not depend on how the surface might be embedded in 3-dimensional space or 2-dimensional space.

In 1821, he was made a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Gauss was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1822.

Magnetism

In 1831, Gauss developed a fruitful collaboration with the physics professor Wilhelm Weber, leading to new knowledge in magnetism (including finding a representation for the unit of magnetism in terms of mass, charge, and time) and the discovery of Kirchhoff's circuit laws in electricity. It was during this time that he formulated his namesake law. They constructed the first electromechanical telegraph in 1833, which connected the observatory with the institute for physics in Göttingen. Gauss ordered a magnetic observatory to be built in the garden of the observatory, and with Weber founded the "Magnetischer Verein" (magnetic association),

which supported measurements of Earth's magnetic field in many regions

of the world. He developed a method of measuring the horizontal

intensity of the magnetic field which was in use well into the second

half of the 20th century, and worked out the mathematical theory for

separating the inner and outer (magnetospheric) sources of Earth's magnetic field.

Appraisal

The British mathematician Henry John Stephen Smith (1826–1883) gave the following appraisal of Gauss:

If we except the great name of Newton it is probable that no mathematicians of any age or country have ever surpassed Gauss in the combination of an abundant fertility of invention with an absolute rigorousness in demonstration, which the ancient Greeks themselves might have envied. It may seem paradoxical, but it is probably nevertheless true that it is precisely the efforts after logical perfection of form which has rendered the writings of Gauss open to the charge of obscurity and unnecessary difficulty. Gauss says more than once that, for brevity, he gives only the synthesis, and suppresses the analysis of his propositions. If, on the other hand, we turn to a memoir of Euler's, there is a sort of free and luxuriant gracefulness about the whole performance, which tells of the quiet pleasure which Euler must have taken in each step of his work. It is not the least of Gauss's claims to the admiration of mathematicians, that, while fully penetrated with a sense of the vastness of the science, he exacted the utmost rigorousness in every part of it, never passed over a difficulty, as if it did not exist, and never accepted a theorem as true beyond the limits within which it could actually be demonstrated.

Anecdotes

There

are several stories of his early genius. According to one, his gifts

became very apparent at the age of three when he corrected, mentally and

without fault in his calculations, an error his father had made on

paper while calculating finances.

Another story has it that in primary school after the young Gauss

misbehaved, his teacher, J.G. Büttner, gave him a task: add a list of integers in arithmetic progression;

as the story is most often told, these were the numbers from 1 to 100.

The young Gauss reputedly produced the correct answer within seconds, to

the astonishment of his teacher and his assistant Martin Bartels.

Gauss's presumed method was to realize that pairwise addition of

terms from opposite ends of the list yielded identical intermediate

sums: 1 + 100 = 101, 2 + 99 = 101, 3 + 98 = 101, and so on, for a total sum of 50 × 101 = 5050.

However, the details of the story are at best uncertain; some authors, such as Joseph Rotman in his book A first course in Abstract Algebra, question whether it ever happened.

He referred to mathematics as "the queen of sciences" and supposedly once espoused a belief in the necessity of immediately understanding Euler's identity as a benchmark pursuant to becoming a first-class mathematician.

Commemorations

German 10-Deutsche Mark Banknote (1993; discontinued) featuring Gauss

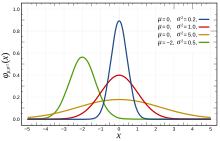

From 1989 through 2001, Gauss's portrait, a normal distribution curve and some prominent Göttingen buildings were featured on the German ten-mark banknote. The reverse featured the approach for Hanover.

Germany has also issued three postage stamps honoring Gauss. One (no.

725) appeared in 1955 on the hundredth anniversary of his death; two

others, nos. 1246 and 1811, in 1977, the 200th anniversary of his birth.

Daniel Kehlmann's 2005 novel Die Vermessung der Welt, translated into English as Measuring the World

(2006), explores Gauss's life and work through a lens of historical

fiction, contrasting them with those of the German explorer Alexander von Humboldt. A film version directed by Detlev Buck was released in 2012.

In 2007 a bust of Gauss was placed in the Walhalla temple.

The numerous things named in honor of Gauss include:

- The Normal Distribution, also known at the Gaussian distribution, the most common bell curve in statistics.

- The Gauss Prize, one of the highest honors in mathematics

- gauss, the CGS unit for magnetic field

In 1929 the Polish mathematician Marian Rejewski, who helped to solve the German Enigma cipher machine in December 1932, began studying actuarial statistics at Göttingen. At the request of his Poznań University professor, Zdzisław Krygowski, on arriving at Göttingen Rejewski laid flowers on Gauss's grave.

On 30 April 2018, Google honored Gauss in his would-be 241st birthday with a Google Doodle showcased in Europe, Russia, Israel, Japan, Taiwan, parts of Southern and Central America and the United States.

Carl Friedrich Gauss, who also introduced the so called Gaussian logarithms, sometimes gets confused with Friedrich Gustav Gauss(1829–1915), a German geologist, who also published some well-known logarithm tables used up into the early 1980s.

Writings

- 1799: Doctoral dissertation on the fundamental theorem of algebra, with the title: Demonstratio nova theorematis omnem functionem algebraicam rationalem integram unius variabilis in factores reales primi vel secundi gradus resolvi posse ("New proof of the theorem that every integral algebraic function of one variable can be resolved into real factors (i.e., polynomials) of the first or second degree")

- 1801: Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (Latin). A German translation by H. Maser "Untersuchungen über höhere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithmeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition)". New York: Chelsea. 1965. ISBN 0-8284-0191-8., pp. 1–453. English translation by Arthur A. Clarke "Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (Second, corrected edition)". New York: Springer. 1986. ISBN 0-387-96254-9..

- 1808: "Theorematis arithmetici demonstratio nova". Göttingen: Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis. 16.. German translation by H. Maser "Untersuchungen über höhere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithmeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition)". New York: Chelsea. 1965. ISBN 0-8284-0191-8., pp. 457–462 [Introduces Gauss's lemma, uses it in the third proof of quadratic reciprocity]

- 1809: Theoria Motus Corporum Coelestium in sectionibus conicis solem ambientium (Theorie der Bewegung der Himmelskörper, die die Sonne in Kegelschnitten umkreisen), Theory of the Motion of Heavenly Bodies Moving about the Sun in Conic Sections (English translation by C.H. Davis), reprinted 1963, Dover, New York.

- 1811: "Summatio serierun quarundam singularium". Göttingen: Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis.. German translation by H. Maser "Untersuchungen über höhere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithmeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition)". New York: Chelsea. 1965. ISBN 0-8284-0191-8., pp. 463–495 [Determination of the sign of the quadratic Gauss sum, uses this to give the fourth proof of quadratic reciprocity]

- 1812: Disquisitiones Generales Circa Seriem Infinitam

- 1818: "Theorematis fundamentallis in doctrina de residuis quadraticis demonstrationes et amplicationes novae". Göttingen: Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis.. German translation by H. Maser "Untersuchungen über höhere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithmeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition)". New York: Chelsea. 1965. ISBN 0-8284-0191-8., pp. 496–510 [Fifth and sixth proofs of quadratic reciprocity]

- 1821, 1823 and 1826: Theoria combinationis observationum erroribus minimis obnoxiae. Drei Abhandlungen betreffend die Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung als Grundlage des Gauß'schen Fehlerfortpflanzungsgesetzes. (Three essays concerning the calculation of probabilities as the basis of the Gaussian law of error propagation) English translation by G.W. Stewart, 1987, Society for Industrial Mathematics.

- 1827: Disquisitiones generales circa superficies curvas, Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingesis Recentiores. Volume VI, pp. 99–146. "General Investigations of Curved Surfaces" (published 1965) Raven Press, New York, translated by J.C.Morehead and A.M.Hiltebeitel

- 1828: "Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio prima". Göttingen: Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis. 6.. German translation by H. Maser

- 1828: "Untersuchungen über höhere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithmeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition)". New York: Chelsea. 1965: 511–533. ISBN 0-8284-0191-8. [Elementary facts about biquadratic residues, proves one of the supplements of the law of biquadratic reciprocity (the biquadratic character of 2)]

- 1832: "Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio secunda". Göttingen: Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis. 7.. German translation by H. Maser "Untersuchungen über höhere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithmeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition)". New York: Chelsea. 1965. ISBN 0-8284-0191-8., pp. 534–586 [Introduces the Gaussian integers, states (without proof) the law of biquadratic reciprocity, proves the supplementary law for 1 + i]

- "Intensitas vis magneticae terrestris ad mensuram absolutam revocata". Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis Recentiores. 8: 3–44. 1832. English translation

- 1843/44: Untersuchungen über Gegenstände der Höheren Geodäsie. Erste Abhandlung, Abhandlungen der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Göttingen. Zweiter Band, pp. 3–46

- 1846/47: Untersuchungen über Gegenstände der Höheren Geodäsie. Zweite Abhandlung, Abhandlungen der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Göttingen. Dritter Band, pp. 3–44

- Mathematisches Tagebuch 1796–1814, Ostwaldts Klassiker, Verlag Harri Deutsch 2005, mit Anmerkungen von Neumamn, ISBN 978-3-8171-3402-1 (English translation with annotations by Jeremy Gray: Expositiones Math. 1984)