The early history of radio is the history of technology that produces and uses radio instruments that use radio waves. Within the timeline of radio, many people contributed theory and inventions in what became radio. Radio development began as "wireless telegraphy". Later radio history increasingly involves matters of broadcasting.

After the discovery of these "Hertzian waves" (it would take almost 20 years for the term "radio" to be universally adopted for this type of electromagnetic radiation) many scientists and inventors experimented with wireless transmission, some trying to develop a system of communication, some intentionally using these new Hertzian waves, some not. Maxwell's theory showing that light and Hertzian electromagnetic waves were the same phenomenon at different wavelengths led "Maxwellian" scientist such as John Perry, Frederick Thomas Trouton and Alexander Trotter to assume they would be analogous to optical signaling and the Serbian American engineer Nikola Tesla to consider them relatively useless for communication since "light" could not transmit further than line of sight. In 1892 the physicist William Crookes wrote on the possibilities of wireless telegraphy based on Hertzian waves and in 1893 Tesla proposed a system for transmitting intelligence and wireless power using the earth as the medium. Others, such as Amos Dolbear, Sir Oliver Lodge, Reginald Fessenden, and Alexander Popov were involved in the development of components and theory involved with the transmission and reception of airborne electromagnetic waves for their own theoretical work or as a potential means of communication.

Over several years starting in 1894 the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi built the first complete, commercially successful wireless telegraphy system based on airborne Hertzian waves (radio transmission). Marconi demonstrated the application of radio in military and marine communications and started a company for the development and propagation of radio communication services and equipment.

In 1878, David E. Hughes noticed that sparks could be heard in a telephone receiver when experimenting with his carbon microphone. He developed this carbon-based detector further and eventually could detect signals over a few hundred yards. He demonstrated his discovery to the Royal Society in 1880, but was told it was merely induction, and therefore abandoned further research. Thomas Edison came across the electromagnetic phenomenon while experimenting with a telegraph at Menlo Park. He noted an unexplained transmission effect while experimenting with a telegraph. He referred to this as etheric force in an announcement on November 28, 1875. Elihu Thomson published his findings on Edison's new "force", again attributing it to induction, an explanation that Edison accepted. Edison would go on the next year to take out U.S. Patent 465,971 on a system of electrical wireless communication between ships based on electrostatic coupling using the water and elevated terminals. Although this was not a radio system the Marconi Company would purchase the rights in 1903 to protect them legally from lawsuits.

After learning of Hertz' demonstrations of wireless transmission, inventor Nikola Tesla began developing his own systems based on Hertz' and Maxwell's ideas, primarily working toward a means of wireless lighting, and power distribution. Tesla, concluding that Hertz had not demonstrated airborne electromagnetic waves (radio transmission), went on to develop a system based on what he thought was the primary conductor, the earth. In 1893 demonstrations of his ideas, in St. Louis, Missouri and at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Tesla proposed this wireless power technology could also incorporate a system for the telecommunication of information.

In a lecture on the work of Hertz, shortly after his death, Professors Oliver Lodge and Alexander Muirhead demonstrated wireless signaling using Hertzian (radio) waves in the lecture theater of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History on August 14, 1894. During the demonstration radio waves were sent from the neighboring Clarendon Laboratory building, and received by apparatus in the lecture theater.

Building on the work of Lodge, the Bengali Indian physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose ignited gunpowder and rang a bell at a distance, using millimeter-range-wavelength microwaves, in a November 1894 public demonstration at the Town Hall of Kolkata, India. Bose wrote in a Bengali essay, "Adrisya Alok" ("Invisible Light"), "The invisible light can easily pass through brick walls, buildings etc. Therefore, messages can be transmitted by means of it without the mediation of wires." Bose's first scientific paper, "On polarisation of electric rays by double-refracting crystals" was communicated to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in May 1895.

Following that, Bose produced a series of articles in English, one after another. His second paper was communicated to the Royal Society of London by Lord Rayleigh in October 1895. In December 1895, the London journal The Electrician (Vol. 36) published Bose's paper, "On a new electro-polariscope". At that time, the word 'coherer', coined by Lodge, was used in the English-speaking world to mean Hertzian wave receivers or detectors. The Electrician (December 1895) readily commented on Bose's coherer. The Englishman (18 January 1896) quoted from The Electrician and commented as follows: "Should Professor Bose succeed in perfecting and patenting his ‘Coherer’, we may in time see the whole system of coast lighting throughout the navigable world revolutionised by an Indian Bengali scientist working single handed[ly] in our Presidency College Laboratory." Bose planned to "perfect his coherer", but never thought of patenting it.

In 1895, conducting experiments along the lines of Hertz's research, Alexander Stepanovich Popov built his first radio receiver, which contained a coherer. Popover further refined his invention as a lightning detector and presented to the Russian Physical and Chemical Society on May 7, 1895. A depiction of the lightning detector was printed in the Journal of the Russian Physical and Chemical Society the same year (publication of the minutes 15/201 of this session – December issue of the journal RPCS). An earlier description of the device was given by Dmitry Aleksandrovich Lachinov in July 1895 in the second edition of his course "Fundamentals of Meteorology and Climatology", which was the first such course in Russia. Popov's receiver was created on the improved basis of Lodge's receiver, and originally intended for reproduction of its experiments.

Summary

Invention

The idea of wireless communication predates the discovery of "radio" with experiments in "wireless telegraphy" via inductive and capacitive induction and transmission through the ground, water, and even train tracks from the 1830s on. James Clerk Maxwell showed in theoretical and mathematical form in 1864 that electromagnetic waves could propagate through free space. It is likely that the first intentional transmission of a signal by means of electromagnetic waves was performed in an experiment by David Edward Hughes around 1880, although this was considered to be induction at the time. In 1888 Heinrich Rudolf Hertz was able to conclusively prove transmitted airborne electromagnetic waves in an experiment confirming Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism.After the discovery of these "Hertzian waves" (it would take almost 20 years for the term "radio" to be universally adopted for this type of electromagnetic radiation) many scientists and inventors experimented with wireless transmission, some trying to develop a system of communication, some intentionally using these new Hertzian waves, some not. Maxwell's theory showing that light and Hertzian electromagnetic waves were the same phenomenon at different wavelengths led "Maxwellian" scientist such as John Perry, Frederick Thomas Trouton and Alexander Trotter to assume they would be analogous to optical signaling and the Serbian American engineer Nikola Tesla to consider them relatively useless for communication since "light" could not transmit further than line of sight. In 1892 the physicist William Crookes wrote on the possibilities of wireless telegraphy based on Hertzian waves and in 1893 Tesla proposed a system for transmitting intelligence and wireless power using the earth as the medium. Others, such as Amos Dolbear, Sir Oliver Lodge, Reginald Fessenden, and Alexander Popov were involved in the development of components and theory involved with the transmission and reception of airborne electromagnetic waves for their own theoretical work or as a potential means of communication.

Over several years starting in 1894 the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi built the first complete, commercially successful wireless telegraphy system based on airborne Hertzian waves (radio transmission). Marconi demonstrated the application of radio in military and marine communications and started a company for the development and propagation of radio communication services and equipment.

19th century

The meaning and usage of the word "radio" has developed in parallel with developments within the field of communications and can be seen to have three distinct phases: electromagnetic waves and experimentation; wireless communication and technical development; and radio broadcasting and commercialization. In an 1864 presentation, published in 1865, James Clerk Maxwell proposed his theories and mathematical proofs on electromagnetism that showed that light and other phenomena were all types of electromagnetic waves propagating through free space. In 1886–88 Heinrich Rudolf Hertz conducted a series of experiments that proved the existence of Maxwell's electromagnetic waves, using a frequency in what would later be called the radio spectrum. Many individuals—inventors, engineers, developers and businessmen—constructed systems based on their own understanding of these and other phenomena, some predating Maxwell and Hertz's discoveries. Thus "wireless telegraphy" and radio wave-based systems can be attributed to multiple "inventors". Development from a laboratory demonstration to a commercial entity spanned several decades and required the efforts of many practitioners.In 1878, David E. Hughes noticed that sparks could be heard in a telephone receiver when experimenting with his carbon microphone. He developed this carbon-based detector further and eventually could detect signals over a few hundred yards. He demonstrated his discovery to the Royal Society in 1880, but was told it was merely induction, and therefore abandoned further research. Thomas Edison came across the electromagnetic phenomenon while experimenting with a telegraph at Menlo Park. He noted an unexplained transmission effect while experimenting with a telegraph. He referred to this as etheric force in an announcement on November 28, 1875. Elihu Thomson published his findings on Edison's new "force", again attributing it to induction, an explanation that Edison accepted. Edison would go on the next year to take out U.S. Patent 465,971 on a system of electrical wireless communication between ships based on electrostatic coupling using the water and elevated terminals. Although this was not a radio system the Marconi Company would purchase the rights in 1903 to protect them legally from lawsuits.

Hertzian waves

Between 1886 and 1888 Heinrich Rudolf Hertz published the results of his experiments wherein he was able to transmit electromagnetic waves (radio waves) through the air, proving Maxwell's electromagnetic theory. Thus, given Hertz comprehensive discoveries, radio waves were referred to as "Hertzian waves". Between 1890 and 1892 physicists such as John Perry, Frederick Thomas Trouton and William Crookes proposed electromagnetic or Hertzian waves as a navigation aid or means of communication, with Crookes writing on the possibilities of wireless telegraphy based on Hertzian waves in 1892.After learning of Hertz' demonstrations of wireless transmission, inventor Nikola Tesla began developing his own systems based on Hertz' and Maxwell's ideas, primarily working toward a means of wireless lighting, and power distribution. Tesla, concluding that Hertz had not demonstrated airborne electromagnetic waves (radio transmission), went on to develop a system based on what he thought was the primary conductor, the earth. In 1893 demonstrations of his ideas, in St. Louis, Missouri and at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Tesla proposed this wireless power technology could also incorporate a system for the telecommunication of information.

In a lecture on the work of Hertz, shortly after his death, Professors Oliver Lodge and Alexander Muirhead demonstrated wireless signaling using Hertzian (radio) waves in the lecture theater of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History on August 14, 1894. During the demonstration radio waves were sent from the neighboring Clarendon Laboratory building, and received by apparatus in the lecture theater.

Building on the work of Lodge, the Bengali Indian physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose ignited gunpowder and rang a bell at a distance, using millimeter-range-wavelength microwaves, in a November 1894 public demonstration at the Town Hall of Kolkata, India. Bose wrote in a Bengali essay, "Adrisya Alok" ("Invisible Light"), "The invisible light can easily pass through brick walls, buildings etc. Therefore, messages can be transmitted by means of it without the mediation of wires." Bose's first scientific paper, "On polarisation of electric rays by double-refracting crystals" was communicated to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in May 1895.

Following that, Bose produced a series of articles in English, one after another. His second paper was communicated to the Royal Society of London by Lord Rayleigh in October 1895. In December 1895, the London journal The Electrician (Vol. 36) published Bose's paper, "On a new electro-polariscope". At that time, the word 'coherer', coined by Lodge, was used in the English-speaking world to mean Hertzian wave receivers or detectors. The Electrician (December 1895) readily commented on Bose's coherer. The Englishman (18 January 1896) quoted from The Electrician and commented as follows: "Should Professor Bose succeed in perfecting and patenting his ‘Coherer’, we may in time see the whole system of coast lighting throughout the navigable world revolutionised by an Indian Bengali scientist working single handed[ly] in our Presidency College Laboratory." Bose planned to "perfect his coherer", but never thought of patenting it.

In 1895, conducting experiments along the lines of Hertz's research, Alexander Stepanovich Popov built his first radio receiver, which contained a coherer. Popover further refined his invention as a lightning detector and presented to the Russian Physical and Chemical Society on May 7, 1895. A depiction of the lightning detector was printed in the Journal of the Russian Physical and Chemical Society the same year (publication of the minutes 15/201 of this session – December issue of the journal RPCS). An earlier description of the device was given by Dmitry Aleksandrovich Lachinov in July 1895 in the second edition of his course "Fundamentals of Meteorology and Climatology", which was the first such course in Russia. Popov's receiver was created on the improved basis of Lodge's receiver, and originally intended for reproduction of its experiments.

Marconi

British Post Office engineers inspect Guglielmo Marconi's wireless telegraphy (radio) equipment in 1897.

In 1894 the young Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi

began working on the idea of building a commercial wireless telegraphy

system based on the use of Hertzian waves (radio waves), a line of

inquiry that he noted other inventors did not seem to be pursuing.

Marconi read through the literature and used the ideas of others who

were experimenting with radio waves but did a great deal to develop

devices such as portable transmitters and receiver systems that could

work over long distances, turning what was essentially a laboratory experiment into a useful communication system.

By August 1895 Marconi was field testing his system but even with

improvements he was only able to transmit signals up to one-half mile, a

distance Oliver Lodge had predicted in 1894 as the maximum transmission

distance for radio waves. Marconi raised the height of his antenna and

hit upon the idea of grounding his transmitter and receiver. With these

improvements the system was capable of transmitting signals up to 2

miles (3.2 km) and over hills. Marconi's experimental apparatus proved to be the first engineering-complete, commercially successful radio transmission system. Marconi's apparatus is also credited with saving the 700 people who survived the tragic Titanic disaster.

In 1896, Marconi was awarded British patent 12039, Improvements in transmitting electrical impulses and signals and in apparatus there-for, the first patent ever issued for a Hertzian wave (radio wave) base wireless telegraphic system. In 1897, he established a radio station on the Isle of Wight, England. Marconi opened his "wireless" factory in the former silk-works at Hall Street, Chelmsford,

England in 1898, employing around 60 people. Shortly after the 1900s,

Marconi held the patent rights for radio. Marconi would go on to win the

Nobel Prize in Physics in 1909 and be more successful than any other inventor in his ability to commercialize radio and its associated equipment into a global business.

In the US some of his subsequent patented refinements (but not his

original radio patent) would be overturned in a 1935 court case (upheld

by the US Supreme Court in 1943).

20th century

In 1900, Brazilian priest Roberto Landell de Moura transmitted the human voice wirelessly. According to the newspaper Jornal do Comercio

(June 10, 1900), he conducted his first public experiment on June 3,

1900, in front of journalists and the General Consul of Great Britain,

C.P. Lupton, in São Paulo,

Brazil, for a distance of approximately 5.0 miles (8 km). The points of

transmission and reception were Alto de Santana and Paulista Avenue.

One year after that experiment, de Moura received his first

patent from the Brazilian government. It was described as "equipment for

the purpose of phonetic transmissions through space, land and water

elements at a distance with or without the use of wires." Four months

later, knowing that his invention had real value, he left Brazil for the United States with the intent of patenting the machine at the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C.

Having few resources, he had to rely on friends to push his

project. Despite great difficulty, three patents were awarded: "The Wave

Transmitter" (October 11, 1904), which is the precursor of today's

radio transceiver; "The Wireless Telephone" and the "Wireless

Telegraph", both dated November 22, 1904.

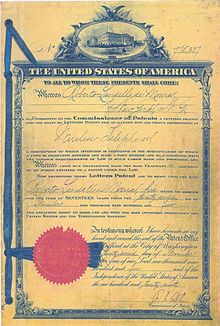

"The Wireless Telephone", U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C.

The next advancement was the vacuum tube detector, invented by Westinghouse engineers. On Christmas Eve 1906, Reginald Fessenden used a synchronous rotary-spark transmitter for the first radio program broadcast, from Ocean Bluff-Brant Rock, Massachusetts. Ships at sea heard a broadcast that included Fessenden playing O Holy Night on the violin and reading a passage from the Bible. This was, for all intents and purposes, the first transmission of what is now known as amplitude modulation or AM radio.

In June 1912 Marconi opened the world's first purpose-built radio factory at New Street Works in Chelmsford, England.

The first radio news program was broadcast August 31, 1920 by station 8MK in Detroit, Michigan, which survives today as all-news format station WWJ

under ownership of the CBS network. The first college radio station

began broadcasting on October 14, 1920 from Union College, Schenectady, New York under the personal call letters of Wendell King, an African-American student at the school.

That month 2ADD (renamed WRUC

in 1947), aired what is believed to be the first public entertainment

broadcast in the United States, a series of Thursday night concerts

initially heard within a 100-mile (160 km) radius and later for a

1,000-mile (1,600 km) radius. In November 1920, it aired the first

broadcast of a sporting event. At 9 pm on August 27, 1920, Sociedad Radio Argentina aired a live performance of Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal from the Coliseo Theater in downtown Buenos Aires.

Only about twenty homes in the city had receivers to tune in this radio

program. Meanwhile, regular entertainment broadcasts commenced in 1922

from the Marconi Research Centre at Writtle, England.

Sports broadcasting began at this time as well, including the college football on radio broadcast of a 1921 West Virginia vs. Pittsburgh football game.

An American girl listens to a radio during the Great Depression

One of the first developments in the early 20th century was that

aircraft used commercial AM radio stations for navigation. This

continued until the early 1960s when VOR systems became widespread. In the early 1930s, single sideband

and frequency modulation were invented by amateur radio operators. By

the end of the decade, they were established commercial modes. Radio was

used to transmit pictures visible as television as early as the 1920s. Commercial television transmissions started in North America and Europe in the 1940s.

In 1947 AT&T commercialized the Mobile Telephone Service.

From its start in St. Louis in 1946, AT&T then introduced Mobile

Telephone Service to one hundred towns and highway corridors by 1948.

Mobile Telephone Service was a rarity with only 5,000 customers placing

about 30,000 calls each week. Because only three radio channels were

available, only three customers in any given city could make mobile

telephone calls at one time.

Mobile Telephone Service was expensive, costing US$15 per month, plus

$0.30–0.40 per local call, equivalent to (in 2012 US dollars) about $176

per month and $3.50–4.75 per call. The Advanced Mobile Phone System analog mobile cell phone system, developed by Bell Labs, was introduced in the Americas in 1978,

gave much more capacity. It was the primary analog mobile phone system

in North America (and other locales) through the 1980s and into the

2000s.

The Regency TR-1, which used Texas Instruments' NPN transistors, was the world's first commercially produced transistor radio.

In 1954, the Regency company introduced a pocket transistor radio, the TR-1, powered by a "standard 22.5 V Battery." In 1955, the newly formed Sony company introduced its first transistorized radio. It was small enough to fit in a vest

pocket, powered by a small battery. It was durable, because it had no

vacuum tubes to burn out. Over the next 20 years, transistors replaced

tubes almost completely except for high-power transmitters.

By 1963, color television was being broadcast commercially

(though not all broadcasts or programs were in color), and the first

(radio) communication satellite, Telstar, was launched. In the late 1960s, the U.S. long-distance telephone network began to convert to a digital network, employing digital radios for many of its links. In the 1970s, LORAN became the premier radio navigation system.

Soon, the U.S. Navy experimented with satellite navigation, culminating in the launch of the Global Positioning System

(GPS) constellation in 1987. In the early 1990s, amateur radio

experimenters began to use personal computers with audio cards to

process radio signals. In 1994, the U.S. Army and DARPA launched an aggressive, successful project to construct a software-defined radio

that can be programmed to be virtually any radio by changing its

software program. Digital transmissions began to be applied to

broadcasting in the late 1990s.

Start of the 20th century

Around the start of the 20th century, the Slaby-Arco wireless system was developed by Adolf Slaby and Georg von Arco. In 1900, Reginald Fessenden

made a weak transmission of voice over the airwaves. In 1901, Marconi

conducted the first successful transatlantic experimental radio

communications. In 1904, The U.S. Patent Office

reversed its decision, awarding Marconi a patent for the invention of

radio, possibly influenced by Marconi's financial backers in the States,

who included Thomas Edison and Andrew Carnegie.

This also allowed the U.S. government (among others) to avoid having to

pay the royalties that were being claimed by Tesla for use of his

patents. For more information see Marconi's radio work. In 1907, Marconi established the first commercial transatlantic radio communications service, between Clifden, Ireland and Glace Bay, Newfoundland.

Donald Manson working as an employee of the Marconi Company (England, 1906)

Julio Cervera Baviera

Julio Cervera Baviera

Julio Cervera Baviera developed radio in Spain around 1902.

Cervera Baviera obtained patents in England, Germany, Belgium, and

Spain. In May–June 1899, Cervera had, with the blessing of the Spanish Army, visited Marconi's radiotelegraphic installations on the English Channel,

and worked to develop his own system. He began collaborating with

Marconi on resolving the problem of a wireless communication system,

obtaining some patents

by the end of 1899. Cervera, who had worked with Marconi and his

assistant George Kemp in 1899, resolved the difficulties of wireless

telegraph and obtained his first patents prior to the end of that year.

On March 22, 1902, Cervera founded the Spanish Wireless Telegraph and

Telephone Corporation and brought to his corporation the patents he had

obtained in Spain, Belgium, Germany and England.

He established the second and third regular radiotelegraph service in

the history of the world in 1901 and 1902 by maintaining regular

transmissions between Tarifa and Ceuta (across the Straits of Gibraltar) for three consecutive months, and between Javea (Cabo de la Nao) and Ibiza (Cabo Pelado). This is after Marconi established the radiotelegraphic service between the Isle of Wight and Bournemouth in 1898. In 1906, Domenico Mazzotto wrote: "In Spain the Minister of War

has applied the system perfected by the commander of military

engineering, Julio Cervera Baviera (English patent No. 20084 (1899))."

Cervera thus achieved some success in this field, but his

radiotelegraphic activities ceased suddenly, the reasons for which are

unclear to this day.

British Marconi

Using various patents, the British Marconi company was established in 1897 and began communication between coast radio stations and ships at sea. This company, along with its subsidiaries Canadian Marconi and American Marconi, had a stranglehold on ship-to-shore communication. It operated much the way American Telephone and Telegraph

operated until 1983, owning all of its equipment and refusing to

communicate with non-Marconi equipped ships. In June 1912, after the RMS Titanic disaster, due to increased production Marconi opened the world's first purpose-built radio factory at New Street Works in Chelmsford, and in 1932 the Marconi Research Laboratory.

Many inventions improved the quality of radio, and amateurs

experimented with uses of radio, thus planting the first seeds of

broadcasting.

Telefunken

The company Telefunken was founded on May 27, 1903, as "Telefunken society for wireless telefon" of Siemens & Halske (S & H) and the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (General Electricity Company) as joint undertakings for radio engineering in Berlin. It continued as a joint venture of AEG and Siemens AG, until Siemens left in 1941. In 1911, Kaiser Wilhelm II sent Telefunken engineers to West Sayville, New York

to erect three 600-foot (180-m) radio towers there. Nikola Tesla

assisted in the construction. A similar station was erected in Nauen, creating the only wireless communication between North America and Europe.

Reginald Fessenden

The invention of amplitude-modulated (AM) radio, so that more than

one station can send signals (as opposed to spark-gap radio, where one

transmitter covers the entire bandwidth of the spectrum) is attributed

to Reginald Fessenden and Lee de Forest. On Christmas Eve 1906, Reginald Fessenden used an Alexanderson alternator and rotary spark-gap transmitter to make the first radio audio broadcast, from Brant Rock, Massachusetts. Ships at sea heard a broadcast that included Fessenden playing O Holy Night on the violin and reading a passage from the Bible.

Ferdinand Braun

In 1909, Marconi and Karl Ferdinand Braun were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for "contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy".

Charles David Herrold

In April 1909 Charles David Herrold, an electronics instructor in San Jose, California constructed a broadcasting station. It used spark gap

technology, but modulated the carrier frequency with the human voice,

and later music. The station "San Jose Calling" (there were no call

letters), continued to eventually become today's KCBS in San Francisco. Herrold, the son of a Santa Clara Valley

farmer, coined the terms "narrowcasting" and "broadcasting",

respectively to identify transmissions destined for a single receiver

such as that on board a ship, and those transmissions destined for a

general audience. (The term "broadcasting" had been used in farming to

define the tossing of seed in all directions.) Charles Herrold did not

claim to be the first to transmit the human voice, but he claimed to be

the first to conduct "broadcasting". To help the radio signal to spread

in all directions, he designed some omnidirectional antennas, which he mounted on the rooftops of various buildings in San Jose. Herrold also claims to be the first broadcaster to accept advertising

(he exchanged publicity for a local record store for records to play on

his station), though this dubious honour usually is foisted on WEAF (1922).

RMS Titanic (April 2, 1912).

In 1912, the RMS Titanic

sank in the northern Atlantic Ocean. After this, wireless telegraphy

using spark-gap transmitters quickly became universal on large ships. In

1913, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea

was convened and produced a treaty requiring shipboard radio stations

to be manned 24 hours a day. A typical high-power spark gap was a

rotating commutator with six to twelve contacts per wheel, nine inches

(229 mm) to a foot wide, driven by about 2,000 volts DC. As the gaps made and broke contact, the radio wave was audible as a tone in a magnetic detector

at a remote location. The telegraph key often directly made and broke

the 2,000 volt supply. One side of the spark gap was directly connected

to the antenna. Receivers with thermionic valves became commonplace before spark-gap transmitters were replaced by continuous wave transmitters.

Harold J. Power

On March 8, 1916, Harold Power with his radio company American Radio and Research Company (AMRAD), broadcast the first continuous broadcast in the world from Tufts University

under the call sign 1XE (it lasted 3 hours). The company later became

the first to broadcast on a daily schedule, and the first to broadcast

radio dance programs, university professor lectures, the weather, and

bedtime stories.

Edwin Armstrong

Inventor Edwin Howard Armstrong

is credited with developing many of the features of radio as it is

known today. Armstrong patented three important inventions that made

today's radio possible. Regeneration, the superheterodyne circuit and wide-band frequency modulation or FM. Regeneration or the use of positive feedback

greatly increased the amplitude of received radio signals to the point

where they could be heard without headphones. The superhet simplified

radio receivers by doing away with the need for several tuning controls.

It made radios more sensitive and selective as well. FM gave listeners a

static-free experience with better sound quality and fidelity than AM.

Wavelength (meters) vs. frequency (kilocycles, kilohertz)

In early radio, and to a limited extent much later, the transmission

signal of the radio station was specified in meters, referring to the wavelength, the length of the radio wave. This is the origin of the terms long wave, medium wave, and short wave radio. Portions of the radio spectrum reserved for specific purposes were often referred to by wavelength: the 40-meter band, used for amateur radio,

for example. The relation between wavelength and frequency is

reciprocal: the higher the frequency, the shorter the wave, and vice

versa.

As equipment progressed, precise frequency control became

possible; early stations often did not have a precise frequency, as it

was affected by the temperature of the equipment, among other factors.

Identifying a radio signal by its frequency rather than its length

proved much more practical and useful, and starting in the 1920s this

became the usual method of identifying a signal, especially in the

United States. Frequencies specified in number of cycles per second

(kilocycles, megacycles) were replaced by the more precise designation

of hertz (cycles per second) about 1965.

Audio broadcasting (1919 to 1950s)

Crystal sets

In the 1920s, the United States government publication, "Construction and Operation of a Simple Homemade Radio Receiving Outfit", showed how almost any person handy with simple tools could a build an effective crystal radio receiver.

The most common type of receiver before vacuum tubes was the crystal set, although some early radios used some type of amplification through electric current or battery. Inventions of the triode amplifier, motor-generator, and detector enabled audio radio. The use of amplitude modulation (AM),

with which more than one station can simultaneously send signals (as

opposed to spark-gap radio, where one transmitter covers the entire

bandwidth of spectra) was pioneered by Fessenden and Lee de Forest.

The art and science of crystal sets is still pursued as a hobby

in the form of simple un-amplified radios that 'runs on nothing,

forever'. They are used as a teaching tool by groups such as the Boy Scouts of America

to introduce youngsters to electronics and radio. As the only energy

available is that gathered by the antenna system, loudness is

necessarily limited.

The first vacuum tubes

During the mid-1920s, amplifying vacuum tubes (or thermionic valves in the UK) revolutionized radio receivers and transmitters. John Ambrose Fleming developed a vacuum tube diode. Lee de Forest placed a screen, added a "grid" electrode, creating the triode. The Dutch company Nederlandsche Radio-Industrie and its owner engineer, Hanso Idzerda, made the first regular wireless broadcast for entertainment from its workshop in The Hague

on 6 November 1919. The company manufactured both transmitters and

receivers. Its popular program was broadcast four nights per week on AM

670 meters, until 1924 when the company ran into financial troubles.

On 27 August 1920, regular wireless broadcasts for entertainment began in Argentina, pioneered by the group around Enrique Telémaco Susini, and spark gap

telegraphy stopped. On 31 August 1920 the first known radio news

program was broadcast by station 8MK, the unlicensed predecessor of WWJ (AM) in Detroit, Michigan. In 1922 regular wireless broadcasts for entertainment began in the UK from the Marconi Research Centre 2MT at Writtle near Chelmsford, England. Early radios ran the entire power of the transmitter through a carbon microphone. In the 1920s, the Westinghouse company bought Lee de Forest's and Edwin Armstrong's patent. During the mid-1920s, Amplifying vacuum tubes (US)/thermionic valves (UK) revolutionized radio receivers and transmitters. Westinghouse engineers developed a more modern vacuum tube.

Political interest in the United Kingdom

The British government and the state-owned postal services found

themselves under massive pressure from the wireless industry (including

telegraphy) and early radio adopters to open up to the new medium. In an

internal confidential report from February 25, 1924, the Imperial Wireless Telegraphy Committee stated:

- We have been asked 'to consider and advise on the policy to be adopted as regards the Imperial Wireless Services so as to protect and facilitate public interest.' It was impressed upon us that the question was urgent. We did not feel called upon to explore the past or to comment on the delays which have occurred in the building of the Empire Wireless Chain. We concentrated our attention on essential matters, examining and considering the facts and circumstances which have a direct bearing on policy and the condition which safeguard public interests.

Licensing of radio stations in the U.S.

- Under the Radio Act of 1912, licensing was the authority of the United States Department of Commerce and Labor (after 1913, the Department of Commerce). There is no known comprehensive record of the stations licensed under this act. The department had no authority to withhold a license from anyone who requested one, and did not regulate frequencies or power.

- Beginning in 1926, the Federal Radio Commission regulated radio use in the United States.

- The Radio Act of 1927 gave the Federal Radio Commission the power to grant and deny licenses, and to assign frequencies and power levels for each licensee. In 1928 it began requiring licenses of existing stations and setting controls on who could broadcast from where on what frequency and at what power. Some stations could not obtain a license and ceased operations. There was no control of the content being broadcast.

- The Communications Act of 1934 abolished the Federal Radio Commission and replaced it with the Federal Communications Commission, giving it authority over broadcast television, then the subject of experiments, and the new radio networks (and famously contributing to the breakup of the NBC Network for anti-trust reasons).

Licensed commercial public radio stations

The question of the 'first' publicly targeted licensed radio station

in the U.S. has more than one answer and depends on semantics.

Settlement of this 'first' question may hang largely upon what

constitutes 'regular' programming.

- It is commonly attributed to KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which in October 1920 received its license and went on the air as the first US licensed commercial broadcasting station on November 2, 1920 with the presidential election results as its inaugural show, but was not broadcasting daily until 1921. (Their engineer Frank Conrad had been broadcasting from on the two call sign signals of 8XK and 8YK since 1916.) Technically, KDKA was the first of several already-extant stations to receive a 'limited commercial' license.

- On February 17, 1919, station 9XM at the University of Wisconsin in Madison broadcast human speech to the public at large. 9XM was first experimentally licensed in 1914, began regular Morse code transmissions in 1916, and its first music broadcast in 1917. Regularly scheduled broadcasts of voice and music began in January 1921. That station is still on the air today as WHA.

- On August 20, 1920 8MK, began broadcasting daily and was later claimed by famed inventor Lee De Forest as the first commercial station. 8MK was licensed to a teenager, Michael DeLisle Lyons, and financed by E. W. Scripps. In 1921 8MK changed to WBL and then to WWJ in 1922, in Detroit. It has carried a regular schedule of programming to the present and also broadcast the 1920 presidential election returns just as KDKA did. Inventor Lee DeForest claims to have been present during 8MK's earliest broadcasts, since the station was using a transmitter sold by his company.

- The first station to receive a commercial license was WBZ, then in Springfield, Massachusetts. Lists provided to the Boston Globe by the U.S. Department of Commerce showed that WBZ received its commercial license on 15 September 1921; another Westinghouse station, WJZ, then in Newark, New Jersey, received its commercial license on November 7, the same day as KDKA did. What separates WJZ and WBZ from KDKA is the fact that neither of the former stations remain in their original city of license, whereas KDKA has remained in Pittsburgh for its entire existence.

- 2XG: Launched by Lee De Forest in the Highbridge section of New York City, that station began daily broadcasts in 1916. Like most experimental radio stations, however, it had to go off the air when the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, and did not return to the air.

- 1XE: Launched by Harold J. Power in Medford, Massachusetts, 1XE was an experimental station that started broadcasting in 1917. It had to go off the air during World War I, but started up again after the war, and began regular voice and music broadcasts in 1919. However, the station did not receive its commercial license, becoming WGI, until 1922.

- 2XN, broadcasting from the City College of New York

- 2ZK, broadcasting in New Rochelle, New York

- WWV, the U.S. Government time service, which was believed to have started 6 months before KDKA in Washington, D.C. but in 1966 was transferred to Ft. Collins, Colorado.

- WRUC, located on Union College in Schenectady, New York; was launched as W2XQ

- WHA (AM), located at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin; was launched as 9XM.

- KQV, one of Pittsburgh's five original AM stations, signed on as amateur station "8ZAE" on November 19, 1919, but did not receive a commercial license until January 9, 1922.

Outside the United States there are also claims for the first radio stations:

- XWA, Marconi's broadcast station in Montreal, Canada, since 1919 (was CFCF, later CINW and shut down in February 2010)

- On August 27, 1920 the Argentina Station started the first transmission from Coliseo Theatre at Buenos Aires, Argentina. Later that station received the name LOR Radio Argentina, and finally LR2 Radio Argentina. That station was in service until 31 December 1997 at 1110 kHz.

Broadcasting was not yet supported by advertising or listener sponsorship.

The stations owned by manufacturers and department stores were

established to sell radios and those owned by newspapers to sell

newspapers and express the opinions of the owners. In the 1920s, radio

was first used to transmit pictures visible as television. During the

early 1930s, single sideband (SSB) and frequency modulation (FM) were invented by amateur radio operators. By 1940, they were established commercial modes.

Westinghouse was brought into the patent allies group, which included General Electric, American Telephone and Telegraph, and Radio Corporation of America,

and became a part owner of RCA. All radios manufactured by GE and

Westinghouse were sold under the RCA name, 60% GE and 40% Westinghouse.

ATT's Western Electric

would build radio transmitters. The patent allies attempted to set up a

monopoly, but they failed due to successful competition. Much to the

dismay of the patent allies, several of the contracts for inventor's

patents held clauses protecting "amateurs" and allowing them to use the

patents. Whether the competing manufacturers were really amateurs was

ignored by these competitors.

These features arose:

- Commercial (United States) or governmental (Europe) station networks

- Federal Radio Commission

- Federal Communications Commission

- CCIR

- Birth of the soap opera

- Race towards shorter waves and FM

FM and television start

In 1933, FM radio was patented by inventor Edwin H. Armstrong. FM uses frequency modulation of the radio wave to reduce static and interference from electrical equipment and the atmosphere. In 1937, W1XOJ, the first experimental FM radio station, was granted a construction permit by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC). In the 1930s, regular analog television

broadcasting began in some parts of Europe and North America. By the

end of the decade there were roughly 25,000 all-electronic television

receivers in existence worldwide, the majority of them in the UK. In the

US, Armstrong's FM system was designated by the FCC to transmit and

receive television sound.

FM in Europe

After World War II, FM radio broadcasting was introduced in Germany. At a meeting in Copenhagen

in 1948, a new wavelength plan was set up for Europe. Because of the

recent war, Germany (which did not exist as a state and so was not

invited) was only given a small number of medium-wave

frequencies, which were not very good for broadcasting. For this reason

Germany began broadcasting on UKW ("Ultrakurzwelle", i.e. ultra short

wave, nowadays called VHF) which was not covered by the Copenhagen plan. After some amplitude modulation

experience with VHF, it was realized that FM radio was a much better

alternative for VHF radio than AM. Because of this history FM Radio is

still referred to as "UKW Radio" in Germany. Other European nations

followed a bit later, when the superior sound quality of FM and the

ability to run many more local stations because of the more limited

range of VHF broadcasts were realized.

Later 20th century developments

In 1954 Regency introduced a pocket transistor radio, the TR-1, powered by a "standard 22.5V Battery". In 1960 Sony

introduced their first transistorized radio, small enough to fit in a

vest pocket, and able to be powered by a small battery. It was durable,

because there were no tubes to burn out. Over the next twenty years,

transistors displaced tubes almost completely except for picture tubes and very high power or very high frequency uses.

In the early 1960s, VOR systems finally became widespread for aircraft navigation; before that, aircraft used commercial AM radio stations for navigation. (AM stations are still marked on U.S. aviation charts).

Color television and digital

- 1953: NTSC compatible color television introduced in the US.

- 1962: Telstar 1, the first communications satellite, relayed the first publicly available live transatlantic television signal.

- Late 1960s: The US long-distance telephone network began to convert to a digital network, employing digital radios for many of its links.

- 1970s: LORAN became the premier radio navigation system. Soon, the US Navy experimented with satellite navigation.

- 1987: The GPS constellation of satellites was launched.

- Early 1990s: Amateur radio experimenters began to use personal computers with audio cards to process radio signals.

- 1994: The US Army and DARPA launched an aggressive successful project to construct a software radio that could become a different radio on the fly by changing software.

- Late 1990s: Digital transmissions began to be applied to broadcasting.

- 2015: The first all-digital radio transmitter, called Pizzicato, was introduced.

Telex on radio

Telegraphy did not go away on radio. Instead, the degree of automation increased. On land-lines in the 1930s, teletypewriters automated encoding, and were adapted to pulse-code dialing to automate routing, a service called telex.

For thirty years, telex was the cheapest form of long-distance

communication, because up to 25 telex channels could occupy the same

bandwidth as one voice channel. For business and government, it was an

advantage that telex directly produced written documents.

Telex systems were adapted to short-wave radio by sending tones over single sideband. CCITT

R.44 (the most advanced pure-telex standard) incorporated

character-level error detection and retransmission as well as automated

encoding and routing. For many years, telex-on-radio (TOR) was the only

reliable way to reach some third-world countries. TOR remains reliable,

though less-expensive forms of e-mail are displacing it. Many national

telecom companies historically ran nearly pure telex networks for their

governments, and they ran many of these links over short wave radio.

Documents including maps and photographs went by radiofax, or wireless photoradiogram, invented in 1924 by Richard H. Ranger of Radio Corporation of America (RCA). This method prospered in the mid-20th century and faded late in the century.

Mobile phones

In 1947 AT&T commercialized the Mobile Telephone Service.

From its start in St. Louis in 1946, AT&T then introduced Mobile

Telephone Service to one hundred towns and highway corridors by 1948.

Mobile Telephone Service was a rarity with only 5,000 customers placing

about 30,000 calls each week. Because only

three radio channels were available, only three customers in any given

city could make mobile telephone calls at one time.

Mobile Telephone Service was expensive, costing US$15 per month, plus

$0.30–0.40 per local call, equivalent to (in 2012 US dollars) about $176

per month and $3.50–4.75 per call. The Advanced Mobile Phone System analog mobile cell phone system, developed by Bell Labs, was introduced in the Americas in 1978, gave much more capacity. It was the primary analog mobile phone system in North America (and other locales) through the 1980s and into the 2000s.

Broadcast and copyright

When radio was introduced in the early 1920s, many predicted it would kill the phonograph record

industry. Radio was a free medium for the public to hear music for

which they would normally pay. While some companies saw radio as a new

avenue for promotion, others feared it would cut into profits from

record sales and live performances. Many record companies would not

license their records to be played over the radio, and had their major

stars sign agreements that they would not perform on radio broadcasts.

Indeed, the music recording industry had a severe drop in profits

after the introduction of the radio. For a while, it appeared as though

radio was a definite threat to the record industry. Radio ownership

grew from two out of five homes in 1931 to four out of five homes in

1938. Meanwhile, record sales fell from $75 million in 1929 to $26

million in 1938 (with a low point of $5 million in 1933), though the

economics of the situation were also affected by the Great Depression.

The copyright owners were concerned that they would see no gain

from the popularity of radio and the ‘free’ music it provided. Luckily,

what they needed to make this new medium work for them already existed

in previous copyright law. The copyright holder for a song had control

over all public performances ‘for profit.’ The problem now was proving

that the radio industry, which was just figuring out for itself how to

make money from advertising and currently offered free music to anyone

with a receiver, was making a profit from the songs.

The test case was against Bamberger's Department Store in Newark, New Jersey

in 1922. The store was broadcasting music throughout its store on the

radio station WOR. No advertisements were heard, except at the beginning

of the broadcast which announced "L. Bamberger and Co., One of

America's Great Stores, Newark, New Jersey." It was determined through

this and previous cases (such as the lawsuit against Shanley's

Restaurant) that Bamberger was using the songs for commercial gain, thus

making it a public performance for profit, which meant the copyright

owners were due payment.

With this ruling the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers

(ASCAP) began collecting licensing fees from radio stations in 1923.

The beginning sum was $250 for all music protected under ASCAP, but for

larger stations the price soon ballooned to $5,000. Edward Samuels

reports in his book The Illustrated Story of Copyright that

"radio and TV licensing represents the single greatest source of revenue

for ASCAP and its composers […] and [a]n average member of ASCAP gets

about $150–$200 per work per year, or about $5,000-$6,000 for all of a

member's compositions." Not long after the Bamberger ruling, ASCAP had

to once again defend their right to charge fees, in 1924. The Dill Radio

Bill would have allowed radio stations to play music without paying and

licensing fees to ASCAP or any other music-licensing corporations. The

bill did not pass.