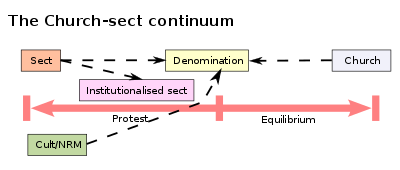

Howard P. Becker's church–sect typology, based on Ernst Troeltsch's original theory and providing the basis for the modern concepts of cults, sects, and new religious movements

In modern English, the term cult has come to usually refer to a social group defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs, or its common interest in a particular personality, object or goal. This sense of the term is controversial and it has divergent definitions in both popular culture and academia and it also has been an ongoing source of contention among scholars across several fields of study. It is usually considered pejorative.

In the sociological classifications of religious movements, a cult is a social group with socially deviant or novel beliefs and practices, although this is often unclear.

Other researchers present a less-organized picture of cults, saying

that they arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices. Groups said to be cults range in size from local groups with a few members to international organizations with millions.

An older sense of the word cult—covered in a different article—is

a set of religious devotional practices that are conventional within

their culture and related to a particular figure, and often associated

with a particular place. References to the "cult" of, for example, a

particular Catholic saint, or the imperial cult of ancient Rome, use this sense of the word.

Beginning in the 1930s, cults became the object of sociological study in the context of the study of religious behavior. From the 1940s the Christian countercult movement has opposed some sects and new religious movements, and it labelled them as cults for their "un-Christian" unorthodox beliefs. The secular anti-cult movement began in the 1970s and it opposed certain groups, often charging them with mind control

and partly motivated in reaction to acts of violence committed by some

of their members. Some of the claims and actions of the anti-cult

movement have been disputed by scholars and by the news media, leading

to further public controversy.

The term "new religious movement" refers to religions which have

appeared since the mid-1800s. Many, but not all of them, have been

considered to be cults. Sub-categories of cults include: Doomsday cults, personality cults, political cults, destructive cults, racist cults, polygamist

cults, and terrorist cults. Various national governments have reacted

to cult-related issues in different ways, and this has sometimes led to

controversy.

English-speakers originally used the word "cult" not to describe a group of religionists, but to refer to the act of worship or to a religious ceremony. The English term originated in the early 17th century, borrowed via the French culte, from the Latin noun cultus (worship). The word ultimately derived from the Latin adjective cultus (inhabited, cultivated, worshipped), based on the verb colere (to care, to cultivate).

While the literal original sense of the word in English remains

in use, a derived sense of "excessive devotion" arose in the 19th

century. The terms cult and cultist came into use in medical literature in the United States in the 1930s for what would now be termed "faith healing", especially as practised in the US Holiness movement. This usage experienced a surge of popularity at the time, and extended to other forms of alternative medicine as well.

In the English-speaking world the word "cult" often carries derogatory connotations. It has always been controversial because it is (in a pejorative sense) considered a subjective term, used as an ad hominem attack against groups with differing doctrines or practices.

In the 1970s, with the rise of secular anti-cult movements,

scholars (but not the general public) began abandoning the term "cult".

According to The Oxford Handbook of Religious Movements, "by the

end of the decade, the term 'new religions' would virtually replace

'cult' to describe all of those leftover groups that did not fit easily

under the label of church or sect."

New religious movements

A new religious movement (NRM) is a religious community or spiritual

group of modern origins (since the mid-1800s), which has a peripheral

place within its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel

in origin or part of a wider religion, in which case they are distinct

from pre-existing denominations. In 1999 Eileen Barker

estimated that NRMs, of which some but not all have been labelled as

cults, number in the tens of thousands worldwide, most of which

originated in Asia or Africa; and that the great majority of which have

only a few members, some have thousands and only very few have more than

a million.

In 2007 the religious scholar Elijah Siegler commented that, although

no NRM had become the dominant faith in any country, many of the

concepts which they had first introduced (often referred to as "New Age" ideas) have become part of worldwide mainstream culture.

Scholarly studies

Max Weber (1864–1920), one of the first scholars to study cults.

Sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) found that cults based on charismatic leadership often follow the routinization of charisma.

The concept of a "cult" as a sociological classification was introduced in 1932 by American sociologist Howard P. Becker as an expansion of German theologian Ernst Troeltsch's church–sect typology. Troeltsch's aim was to distinguish between three main types of religious behavior: churchly, sectarian and mystical. Becker created four categories out of Troeltsch's first two by splitting church into "ecclesia" and "denomination", and sect into "sect" and "cult".

Like Troeltsch's "mystical religion", Becker's cults were small

religious groups lacking in organization and emphasizing the private

nature of personal beliefs. Later sociological formulations built on these characteristics, placing an additional emphasis on cults as deviant religious groups "deriving their inspiration from outside of the predominant religious culture".

This is often thought to lead to a high degree of tension between the

group and the more mainstream culture surrounding it, a characteristic

shared with religious sects. In this sociological terminology, sects are products of religious schism and therefore maintain a continuity with traditional beliefs and practices, while cults arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.

In the early 1960s, sociologist John Lofland lived with South Korean missionary Young Oon Kim and some of the first American Unification Church members in California, during which he studied their activities in trying to promote their beliefs and win new members.

Lofland noted that most of their efforts were ineffective and that most

of the people who joined did so because of personal relationships with

other members, often family relationships.

Lofland published his findings in 1964 as a doctoral thesis entitled:

"The World Savers: A Field Study of Cult Processes", and in 1966 in book

form by Prentice-Hall as Doomsday Cult: A Study of Conversion, Proselytization and Maintenance of Faith. It is considered to be one of the most important and widely cited studies of the process of religious conversion.

Sociologist Roy Wallis (1945–1990) argued that a cult is characterized by "epistemological

individualism", meaning that "the cult has no clear locus of final

authority beyond the individual member". Cults, according to Wallis, are

generally described as "oriented towards the problems of individuals,

loosely structured, tolerant [and] non-exclusive", making "few demands

on members", without possessing a "clear distinction between members and

non-members", having "a rapid turnover of membership" and as being

transient collectives with vague boundaries and fluctuating belief

systems. Wallis asserts that cults emerge from the "cultic milieu".

In 1978 Bruce Campbell noted that cults are associated with beliefs in a divine element in the individual. It is either Soul, Self, or True Self.

Cults are inherently ephemeral and loosely organized. There is a major

theme in many of the recent works that show the relationship between

cults and mysticism.

Campbell brings two major types of cults to attention. One is mystical

and the other is instrumental. This can divide the cults into being

either occult or metaphysical

assembly. On the basis that Campbell proposes cults, they are

non-traditional religious groups based on belief in a divine element in

the individual. There is also a third type. This is service-oriented.

Campbell states that "the kinds of stable forms which evolve in the

development of religious organization will bear a significant

relationship to the content of the religious experience of the founder

or founders."

Dick Anthony, a forensic psychologist known for his criticism of brainwashing theory of conversion,

has defended some so-called cults, and in 1988 argued that involvement

in such movements may often have beneficial, rather than harmful

effects, saying "There's a large research literature published in

mainstream journals on the mental health effects of new religions. For

the most part, the effects seem to be positive in any way that's

measurable."

In their 1996 book Theory of Religion, American sociologists Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge propose that the formation of cults can be explained through the rational choice theory. In The Future of Religion they comment "...in the beginning, all religions are obscure, tiny, deviant cult movements". According to Marc Galanter, Professor of Psychiatry at NYU, typical reasons why people join cults include a search for community and a spiritual quest.

Stark and Bainbridge, in discussing the process by which individuals

join new religious groups, have even questioned the utility of the

concept of conversion, suggesting that affiliation is a more useful concept.

J. Gordon Melton stated that in 1970, "one could count the number

of active researchers on new religions on one's hands." James R. Lewis

writes, however, that the "meteoric growth" on this field of study can

be attributed to the cult controversy of the early 1970s, when new

stories about the People's Temple and Heavens Gate were being reported.

Because of a "a wave of nontraditional religiosity" in the late 1960s

and early 1970s, academics perceived new religious movements as

different phenomena from previous religious innovations.

Anti-cult movements

Christian countercult movement

In the 1940s, the long-held opposition by some established Christian denominations to non-Christian religions and/or supposedly heretical, or counterfeit, Christian sects crystallized into a more organized Christian countercult movement

in the United States. For those belonging to the movement, all

religious groups claiming to be Christian, but deemed outside of

Christian orthodoxy, were considered cults. Christian cults are new religious movements which have a Christian background but are considered to be theologically deviant by members of other Christian churches. In his influential book The Kingdom of the Cults (first published in the United States in 1965), Christian scholar Walter Martin

defines Christian cults as groups that follow the personal

interpretation of an individual, rather than the understanding of the

Bible accepted by mainstream Christianity. He mentions The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Christian Science, Jehovah's Witnesses, Unitarian Universalism, and Unity as examples.

The Christian countercult movement asserts that Christian sects

whose beliefs are partially or wholly not in accordance with the Bible

are erroneous. It also states that a religious sect can be considered a

cult if its beliefs involve a denial of what they view as any of the

essential Christian teachings such as salvation, the Trinity, Jesus himself as a person, the ministry of Jesus, the miracles of Jesus, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection of Christ, the Second Coming of Christ, and the Rapture.

Countercult literature usually expresses doctrinal or theological concerns and a missionary or apologetic purpose.

It presents a rebuttal by emphasizing the teachings of the Bible

against the beliefs of non-fundamental Christian sects. Christian

countercult activist writers also emphasize the need for Christians to evangelize to followers of cults.

Secular anti-cult movement

An anti-Aum Shinrikyo protest in Japan, 2009

In the early 1970s, a secular opposition movement to groups

considered cults had taken shape. The organizations that formed the

secular "anti-cult movement" (ACM) often acted on behalf of relatives of "cult" converts who did not believe their loved ones could have altered their lives so drastically by their own free will. A few psychologists and sociologists working in this field suggested that brainwashing techniques were used to maintain the loyalty of cult members.

The belief that cults brainwashed their members became a unifying theme

among cult critics and in the more extreme corners of the anti-cult

movement techniques like the sometimes forceful "deprogramming" of cult members was practiced.

Secular cult opponents belonging to the anti-cult movement

usually define a "cult" as a group that tends to manipulate, exploit,

and control its members. Specific factors in cult behavior are said to

include manipulative and authoritarian mind control over members, communal and totalistic organization, aggressive proselytizing, systematic programs of indoctrination, and perpetuation in middle-class communities.

In the mass media, and among average citizens, "cult" gained an

increasingly negative connotation, becoming associated with things like kidnapping, brainwashing, psychological abuse, sexual abuse and other criminal activity, and mass suicide.

While most of these negative qualities usually have real documented

precedents in the activities of a very small minority of new religious

groups, mass culture often extends them to any religious group viewed as

culturally deviant, however peaceful or law abiding it may be.

While some psychologists were receptive to these theories,

sociologists were for the most part sceptical of their ability to

explain conversion to NRMs. In the late 1980s, psychologists and sociologists started to abandon theories like brainwashing and mind-control. While scholars may believe that various less dramatic coercive

psychological mechanisms could influence group members, they came to

see conversion to new religious movements principally as an act of a rational choice.

Reactions to the anti-cult movements

Because

of the increasingly pejorative use of the words "cult" and "cult

leader" since the cult debate of the 1970s, some academics, in addition

to groups referred to as cults, argue that these are words to be

avoided. Catherine Wessinger (Loyola University New Orleans)

has stated that the word "cult" represents just as much prejudice and

antagonism as racial slurs or derogatory words for women and

homosexuals.

She has argued that it is important for people to become aware of the

bigotry conveyed by the word, drawing attention to the way it

dehumanises the group's members and their children. Labeling a group as subhuman, she says, becomes a justification for violence against it.

She also says that labeling a group a "cult" makes people feel safe,

because the "violence associated with religion is split off from

conventional religions, projected onto others, and imagined to involve

only aberrant groups".

This fails to take into account that child abuse, sexual abuse,

financial extortion and warfare have also been committed by believers of

mainstream religions, but the pejorative "cult" stereotype makes it

easier to avoid confronting this uncomfortable fact.

Sociologist Amy Ryan has argued for the need to differentiate

those groups that may be dangerous from groups that are more benign.

Ryan notes the sharp differences between definition from cult

opponents, who tend to focus on negative characteristics, and those of

sociologists, who aim to create definitions that are value-free. The

movements themselves may have different definitions of religion as well. George Chryssides also cites a need to develop better definitions to allow for common ground in the debate. In Defining Religion in American Law,

Bruce J. Casino presents the issue as crucial to international human

rights laws. Limiting the definition of religion may interfere with

freedom of religion, while too broad a definition may give some

dangerous or abusive groups "a limitless excuse for avoiding all

unwanted legal obligations".

Subcategories

Destructive cults

Jim Jones, the leader of the Peoples Temple

"Destructive cult" generally refers to groups whose members have,

through deliberate action, physically injured or killed other members of

their own group or other people. The Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance

specifically limits the use of the term to religious groups that "have

caused or are liable to cause loss of life among their membership or the

general public". Psychologist Michael Langone, executive director of the anti-cult group International Cultic Studies Association,

defines a destructive cult as "a highly manipulative group which

exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members

and recruits".

John Gordon Clark cited totalitarian systems of governance and an emphasis on money making as characteristics of a destructive cult. In Cults and the Family the authors cite Shapiro, who defines a "destructive cultism" as a sociopathic syndrome,

whose distinctive qualities include: "behavioral and personality

changes, loss of personal identity, cessation of scholastic activities,

estrangement from family, disinterest in society and pronounced mental

control and enslavement by cult leaders".

In the opinion of Benjamin Zablocki, a Professor of Sociology at Rutgers University,

destructive cults are at high risk of becoming abusive to members. He

states that this is in part due to members' adulation of charismatic leaders contributing to the leaders becoming corrupted by power. According to Barrett, the most common accusation made against destructive cults is sexual abuse. According to Kranenborg, some groups are risky when they advise their members not to use regular medical care. This may extend to physical and psychological harm.

Some researchers have criticized the usage of the term

"destructive cult", writing that it is used to describe groups which are

not necessarily harmful in nature to themselves or others. In his book Understanding New Religious Movements, John A. Saliba writes that the term is overgeneralized. Saliba sees the Peoples Temple as the "paradigm of a destructive cult", where those that use the term are implying that other groups will also commit mass suicide.

Writing in the book Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field, contributor Julius H. Rubin complains that the term has been used to discredit certain groups in the court of public opinion. In his work Cults in Context author Lorne L. Dawson writes that although the Unification Church "has not been shown to be violent or volatile", it has been described as a destructive cult by "anticult crusaders". In 2002, the German government was held by Germany's Federal Constitutional Court to have defamed the Osho movement by referring to it, among other things, as a "destructive cult" with no factual basis.

Doomsday cults

"Doomsday cult" is an expression which is used to describe groups that believe in Apocalypticism and Millenarianism, and it can also be used to refer both to groups that predict disaster, and groups that attempt to bring it about. In the 1950s American social psychologist Leon Festinger and his colleagues observed members of a small UFO religion

called the Seekers for several months, and recorded their conversations

both prior to and after a failed prophecy from their charismatic

leader. Their work was later published in the book When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World.

In the late 1980s, doomsday cults were a major topic of news reports,

with some reporters and commentators considering them a serious threat

to society. A 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter found that people turned to a cataclysmic world view after they had repeatedly failed to find meaning in mainstream movements.

Political cults

LaRouche Movement members in Stockholm protesting against the Treaty of Lisbon.

A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in political action and ideology. Groups which some writers have termed "political cults", mostly advocating far-left or far-right agendas, have received some attention from journalists and scholars. In their 2000 book On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left, Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth discuss about a dozen organizations in the United States and Great Britain that they characterize as cults. In a separate article Tourish says that in his usage:

The word cult is not a term of abuse, as this paper tries to explain. It is nothing more than a shorthand expression for a particular set of practices that have been observed in a variety of dysfunctional organisations.

The LaRouche Movement and Gino Parente's National Labor Federation (NATLFED)

are examples of political groups that have been described as "cults",

based in the United States; another is Marlene Dixon's now-defunct Democratic Workers Party (a critical history of the DWP is given in Bounded Choice by Janja A. Lalich, a sociologist and former DWP member).

The Iron Guard movement of interwar Romania has been referred to as a "macabre political cult", a cargo cult and a "cult of martyrdom and violence". As a cult, the Guard found itself in the very peculiar position of being a cult running an entire country for several months between 1940 and 1941.

The followers of Ayn Rand were characterized as a "cult" by economist Murray N. Rothbard during her lifetime, and later by Michael Shermer.

The core group around Rand was called the "Collective" and is now

defunct (the chief group disseminating Rand's ideas today is the Ayn Rand Institute).

Although the Collective advocated an individualist philosophy, Rothbard

claimed they were organized in the manner of a "Leninist" organization.

In Britain, the Workers Revolutionary Party, a Trotskyist group led by Gerry Healy and strongly supported by actress Vanessa Redgrave,

has been described by others, who have been involved in the Trotskyist

movement, as having been a cult or as displaying cult-like

characteristics in the 1970s and 1980s. It is also described as such by Tourish and Wohlforth in their writings.

In his review of Tourish and Wohlforth's book, Bob Pitt, a former

member of the WRP concedes that it had a "cult-like character" but

argues that rather than being typical of the far left, this feature

actually made the WRP atypical and "led to its being treated as a pariah

within the revolutionary left itself".

Workers' Struggle (LO, Lutte ouvrière) in France, publicly headed by Arlette Laguiller but revealed in the 1990s to be directed by Robert Barcia, has often been criticized as a cult, for example by Daniel Cohn-Bendit and his older brother Gabriel Cohn-Bendit, as well as L'Humanité and Libération.

In his book Les Sectes Politiques: 1965–1995 (translation: Political cults: 1965–1995), French writer Cyril Le Tallec considered some religious groups as cults involved in politics, including the League for Catholic Counter-Reformation, the Cultural Office of Cluny, New Acropolis, Sōka Gakkai, the Divine Light Mission, Tradition Family Property (TFP), Longo-Mai, the Supermen Club and the Association for Promotion of the Industrial Arts (Solazaref).

In 1990 Lucy Patrick commented: "Although we live in a democracy,

cult behavior manifests itself in our unwillingness to question the

judgment of our leaders, our tendency to devalue outsiders and to avoid

dissent. We can overcome cult behavior, he says, by recognizing that we

have dependency needs that are inappropriate for mature people, by

increasing anti-authoritarian education, and by encouraging personal

autonomy and the free exchange of ideas."

Polygamist cults

Cults that teach and practice polygamy, marriage between more than two people, most often polygyny,

one man having multiple wives, have long been noted, although they are a

minority. It has been estimated that there are around 50,000 members

of polygamist cults in North America.

Often, polygamist cults are viewed negatively by both legal

authorities and society, and this view sometimes includes negative

perceptions of related mainstream denominations, because of their

perceived links to possible domestic violence and child abuse.

In 1890, the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Wilford Woodruff, issued a public declaration (the Manifesto) announcing that the LDS Church had ceased performing new plural marriages. Anti-Mormon sentiment waned, as did opposition to statehood for Utah. The Smoot Hearings in 1904, which documented that the LDS Church was still practicing polygamy spurred the church to issue a Second Manifesto again claiming that it had ceased performing new plural marriages. By 1910 the LDS Church excommunicated those who entered into or performed new plural marriages. Enforcement of the 1890 Manifesto caused various splinter groups to leave the LDS Church in order to continue the practice of plural marriage. The Church of Jesus Christ Restored is a small sect within the Latter Day Saint movement based in Chatsworth, Ontario,

Canada. It has been labeled a polygamous cult by the news media and has

been the subject of criminal investigation by local authorities.

Racist cults

Cross burning by Ku Klux Klan members in 1915.

Sociologist and historian Orlando Patterson has described the Ku Klux Klan, which arose in the American South after the Civil War, as a heretical Christian cult, and he has also described its persecution of African Americans and others as a form of human sacrifice. Secret Aryan cults in (Germany) and Austria in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a strong influence on the rise of Nazism. Modern white power skinhead groups in the United States tend to use the same recruitment techniques as destructive cults.

Peter Staudenmeier, professor of modern German history at Marquette University describes Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy between occultism and fascism. He analyzes the racist foundations of this movement in detail.

Terrorist cults

In the book Jihad and Sacred Vengeance: Psychological Undercurrents of History, psychiatrist Peter A. Olsson compares Osama bin Laden to certain cult leaders including Jim Jones, David Koresh, Shoko Asahara, Marshall Applewhite, Luc Jouret and Joseph Di Mambro, and he says that each of these individuals fit at least eight of the nine criteria for people with narcissistic personality disorders. In the book Seeking the Compassionate Life: The Moral Crisis for Psychotherapy and Society authors Goldberg and Crespo also refer to Osama bin Laden as a "destructive cult leader".

At a 2002 meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA), anti-cultist Steven Hassan said that Al-Qaida

fulfills the characteristics of a destructive cult. He added: "We need

to apply what we know about destructive mind-control cults, and this

should be a priority in the War on Terrorism.

We need to understand the psychological aspects of how people are

recruited and indoctrinated so we can slow down recruitment. We need to

help counsel former cult members and possibly use some of them in the

war against terrorism."

In an article on Al-Qaida published in The Times, journalist Mary Ann Sieghart

wrote that al-Qaida resembles a "classic cult", commenting: "Al-Qaida

fits all the official definitions of a cult. It indoctrinates its

members; it forms a closed, totalitarian society; it has a self-appointed, messianic and charismatic leader; and it believes that the ends justify the means."

Similar to Al-Qaida, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant adheres to an even more extremist ideology, in which the goal was to create a state i.e. a physical territory governed by its religious leadership's interpretation of shari'ah, which brainwashed and commanded its able-bodied male subjects to go on suicide missions with weapons such as car bombs against its enemies, including deliberately selected civilian targets, such as churches and Shi'ite

mosques among others. They viewed this as a legitimate action, indeed

an obligation. The ultimate purpose of this political-military endeavour

was to eventually usher in the Islamic end times

and have the chance to fight their vision of the apocalyptic battle,

where all their enemies (i.e. anyone who wasn't on their side) would be

annihilated. That endeavour has ultimately failed clearly in 2017 and the hardcore survivors have largely returned to insurgency terrorist operations ever since.

The Shining Path guerrilla movement which was active in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s has variously been described as a "cult" and an intense "cult of personality". The Tamil Tigers have also been described as such by the French magazine L'Express.'

The People's Mujahedin of Iran, a leftist guerrilla movement based in Iraq, has controversially been described as both a political cult and a movement that is abusive towards its own members.

Former Mujaheddin member and now author and academic Dr. Masoud

Banisadr stated in a May 2005 speech in Spain: "If you ask me: are all

cults a terrorist organisation? My answer is no, as there are many

peaceful cults at present around the world and in the history of

mankind. But if you ask me are all terrorist organisations some sort of

cult, my answer is yes. Even if they start as [an] ordinary modern

political party or organisation, to prepare and force their members to

act without asking any moral questions and act selflessly for the cause

of the group and ignore all the ethical, cultural, moral or religious

codes of the society and humanity, those organisations have to change

into a cult. Therefore to understand an extremist or a terrorist

organisation one has to learn about a cult." In 2003, the group ordered some of its members to set themselves on fire, two of whom died.

Regional developments

The application of the labels "cult" or "sect" to religious movements

in government documents signifies the popular and negative use of the

term "cult" in English and a functionally similar use of words

translated as "sect" in several European languages.

Sociologists critical to this negative politicized use of the word

"cult" argue that it may adversely impact the religious freedoms of

group members. At the height of the counter-cult movement and ritual abuse scare of the 1990s, some governments published lists of cults.

While these documents utilize similar terminology they do not

necessarily include the same groups nor is their assessment of these

groups based on agreed criteria. Other governments and world bodies also report on new religious movements but do not use these terms to describe the groups. Since the 2000s, some governments have again distanced themselves from such classifications of religious movements.

While the official response to new religious groups has been mixed

across the globe, some governments aligned more with the critics of

these groups to the extent of distinguishing between "legitimate"

religion and "dangerous", "unwanted" cults in public policy.

Asia

China

Falun Gong books symbolically destroyed by Chinese government

For centuries, governments in China have categorized certain religions as xiejiao (Chinese: 邪教; pinyin: xiéjiào) – sometimes translated as "evil cult" or as "heterodox teaching". In imperial China, the classification of a religion as xiejiao

did not necessarily mean that a religion's teachings were believed to

be false or inauthentic, but rather, the label was applied to religious

groups that were not authorized by the state, or that were seen as

challenging the legitimacy of the state. In modern China, the term xiejiao

continues to be used to denote teachings that the government

disapproves of, and these groups face suppression and punishment by

authorities. Fourteen different groups in China have been listed by the

ministry of public security as xiejiao. In addition, in 1999, Chinese authorities denounced the Falun Gong spiritual practice as a heretical teaching, and they launched a campaign to eliminate it. According to Amnesty International, the persecution of Falun Gong includes a multifaceted propaganda campaign, a program of enforced ideological conversion and re-education, as well as a variety of extralegal coercive measures, such as arbitrary arrests, forced labour, and physical torture, sometimes resulting in death.

Japan

Aum Shinrikyo, which split into Aleph and Hikari no Wa in 2007, has been formally designated a terrorist organization by several countries, including Canada, Kazakhstan.

Russia

In 2008 the Russian Interior Ministry

prepared a list of "extremist groups." At the top of the list were

Islamic groups outside of "traditional Islam," which is supervised by

the Russian government. Next listed were "Pagan cults". In 2009 the Russian Ministry of Justice

created a council which it named "Council of Experts Conducting State

Religious Studies Expert Analysis." The new council listed 80 large

sects which it considered potentially dangerous to Russian society, and

mentioned that there were thousands of smaller ones. Large sects listed

included: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Jehovah's Witnesses, and what were called "neo-Pentecostals."

United States

In the 1970s, the scientific status of the "brainwashing theory" became a central topic in U.S. court cases where the theory was used to try to justify the use of the forceful deprogramming of cult members. Meanwhile, sociologists critical of these theories assisted advocates of religious freedom in defending the legitimacy of new religious movements in court. In the United States religious activities of cults are protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, which prohibits governmental establishment of religion and protects freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly. However, no religious or cult members are granted any special immunity from criminal charges.

Western Europe

France

and Belgium have taken policy positions which accept "brainwashing"

theories uncritically, while other European nations, like Sweden and

Italy, are cautious about brainwashing and have adopted more neutral

responses to new religions. Scholars have suggested that outrage following the mass murder/suicides perpetuated by the Solar Temple as well as the more latent xenophobic and anti-American attitudes have contributed significantly to European anti-cult positions. In the 1980s clergymen and officials of the French government expressed concern that some orders and other groups within the Roman Catholic Church would be adversely affected by anti-cult laws then being considered.