Part of seventh-century casket, depicting the pan-Germanic legend of Weyland Smith, which was apparently also a part of Anglo-Saxon pagan mythology

Paganism is commonly used to refer to various, largely unconnected religions that existed during Antiquity and the Middle Ages, such as the Greco-Roman religions of the Roman Empire, including the Roman imperial cult, the various mystery religions, monotheistic religions such as Neoplatonism and Gnosticism, and more localized ethnic religions practiced both inside and outside the Empire. During the Middle Ages, the term was also adapted to refer to religions practiced outside the former Roman Empire, such as Germanic paganism, Slavic paganism and Baltic paganism.

From the point of view of the early Christians these religions all qualified as ethnic (or gentile, ethnikos, gentilis, the term translating goyim, later rendered as paganus) in contrast with Second Temple Judaism.

By the late Middle Ages, Christianity had eliminated those faiths

referred to as pagan through a mixture of peaceful conversion,

persecution, and military conquest of pagan peoples; the Christianization of Lithuania

in the 1400s is typically considered to mark the end of this process.

The term "pagan" was typically not used to refer to non-Christian

peoples with whom Christians interacted after that point, such as during

colonization.

Pagan influences on Christianity

Pythagoreans celebrate sunrise

By the early 2nd century Christians were no longer seen as a "sect of

Judaism" but were considered by pagans as another "foreign cult" which

had "crept into the Roman world," causing them great concern.

Some argue that looking at pagans in the Roman Empire is not only

complicated by the fact that Christians use the term to define

non-Christians, with the term itself is Christian in origin as it was

used by Christian writers in the early Middle Ages, and information on

pagans themselves is relatively scant. Others noted that pagans may have

been suspicious of refusal by

Christians (then a religious minority) to "sacrifice to the Roman gods,"

posdibly endangering the Roman Empire itself and had, for the pagans, a

"whiff of both sacrilege and treason."

In the course of the Christianisation of Europe in the Early Middle Ages, the Latin adopted many elements of national cult and folk religion, resulting in national churches like Latin, Germanic, Russian, Armenian, Greek, and so on. Some Pagan ceremonies were brought in and the festivals became modern holidays as pagans joined the early church. The Pagan vernal equinox celebration was Christianized and then referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary or Annunciation of the Lord and celebrated as the Feast of the Annunciation. The Germanic Pagan solstice celebrations (Midsummer festivals) are also sometimes referred to by Neopagans and others as Litha, stemming from Bede's De temporum ratione

and the fire festival or Litha was a tradition for many pagans. This

pagan holiday was basically brought in and given a name change, and in Christianity was then associated with the nativity of John the Baptist, which now is observed on the same day, June 24, in the Catholic, Orthodox and some Protestant churches. It is six months before Christmas because Luke 1:26 and Luke 1.36 imply that John the Baptist was born six months earlier than Jesus,

although the Bible does not say at which time of the year this

happened. As some argue, some of the most basic tenets of Christianity

"derive from ancient paganism rather than from the Bible."

In the case of Christmas, Druids, a Pagan priesthood in ancient Britain and France held a 12-day celebration around the

winter solstice, believing it to be part of an annual battle between death and life.

They built huge bonfires and knew that days got longer as the calendar

progesses through the winter season into spring. As such, the current

holiday of Christmas began as a midwinter festival of the Pagans, with

the Christians adopting the tradition of decorating with green plants

from the Druids.

They would also adopt the 12 days of Christmas from the aforementioned

12 day festival held by pagans. Christians would eventually adopt the

cutting down of a tree to decorate and display in their homes, with

German immigrants bringing thus tradition to the United States.

Others put it more plainly, writing that many symbols that "modern-day Christians associate with Christmas have pagan roots."

Martin Luther King, Jr. even wrote about this connection while in late

1949 or early 1950, noting that the place at Bethleham selected by early

Christians as Jesus's birthplace was an early shrine of a pagan god,

Adonis, with the story of resurrection also said to be similar to that

of Adonis. His essay also argued that the descent of Jesus into hell was also borrowed from paganism, as was a baptismal ceremony.

Influence on early Christian theology

Christianity originated in the Roman province of Judaea, a predominantly Jewish society, with traditional philosophies distinct from the Greek thought

which was dominant in the Roman Empire at the time. The conflict

between the two modes of thought is recorded in the Christian

scriptures, in Paul's encounters with Epicurean and Stoic philosophers mentioned in Acts, his diatribe against Greek philosophy in 1st Corinthians, and his warning against vain philosophy in Colossians 2:8.

One early Christian writer of the 2nd and early 3rd century, Clement of Alexandria,

demonstrated the assimilation of Greek thought in writing: "Philosophy

has been given to the Greeks as their own kind of Covenant, their

foundation for the philosophy of Christ... the philosophy of the

Greeks... contains the basic elements of that genuine and perfect

knowledge which is higher than human... even upon those spiritual

objects."

Augustine of Hippo (354–430), who ultimately systematized Christian philosophy after converting to Christianity from Manichaeism, wrote in the late 4th and early 5th century: "But when I read those books of the Platonists I was taught by them to seek incorporeal truth, so I saw your 'invisible things, understood by the things that are made'."

St. Augustine was originally a Manichaean.

Until the 20th century, most of the Western world's concept of Manichaeism came through Augustine's negative polemics against it. According to his Confessions,

after eight or nine years of adhering to the Manichaean faith (as a

member of the Manichaean group of Hearers), he became a Christian and a

potent adversary of Manichaeism. It is speculated by some modern

scholars (Alfred Adam, for example),

that Manichaean ways of thinking had an influence on the development of

some of Augustine's Christian ideas, such as the nature of good and

evil, the idea of Hell, the separation of groups into Elect, Hearers,

and Sinners, the hostility to the flesh and sexual activity, and so on (Manichaeism had originated in a heavily Gnostic area of the Persian empire.) How much influence Manichaeism actually had on Christianity is still being debated.

The Paulicians, Bogomils, and Cathars were dualists and felt that the world was the work of a demiurge of Satanic origin. Whether this was due to influence from Manichaeism or another strand of Gnosticism

has been impossible to determine. The Bogomils and Cathars, in

particular, left few records of their rituals or doctrines, and the link

between them and Manichaeans is unclear. Regardless of its historical

veracity the charge of Manichaeism was leveled at them by contemporary

orthodox opponents, who often tried to fit contemporary heresies with

those combated by the church fathers. Only a minority of Cathars held

that The Evil God (or principle) was as powerful as The Good God (also

called a principle) as Mani did, a belief also known as absolute

dualism. In the case of the Cathars, it seems they adopted the

Manichaean principles of church organization, but none of its religious cosmology. Priscillian and his followers apparently tried to absorb what they thought was the valuable part of Manichaeaism into Christianity.

Origins of Christianity

St. Clement I was an Apostolic Father.

Early Christianity arose as a movement within Second Temple Judaism, following the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. With a missionary commitment to both Jews and Gentiles (non-Jews), Christianity rapidly spread into the greater Roman empire and beyond. Here, Christianity came into contact with the dominant Pagan religions.

By the 2nd century, many Christians were converts from Paganism. These conflicts are recorded in the works of the early Christian writers such as Justin Martyr as well as hostile reports by writers including Tacitus and Suetonius.

Persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire

Christianity was persecuted by Roman imperial authorities early on in its history within the greater empire.

Persecution under Nero, 64–68 AD

The first documented case of imperially-supervised persecution of the Christians in the Roman Empire begins with Nero (37–68). In 64 AD, a great fire broke out in Rome,

destroying portions of the city and economically devastating the Roman

population. Nero himself was suspected as the arsonist by Suetonius, claiming he played the lyre and sang the 'Sack of Ilium' during the fires. In his Annals, Tacitus

(who claimed Nero was in Antium at the time of the fire's outbreak),

stated that "to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and

inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their

abominations, called Christians [or Chrestians] by the populace" (Tacit. Annals XV, see Tacitus on Jesus).

Suetonius, later to the period, does not mention any persecution after

the fire, but in a previous paragraph unrelated to the fire, mentions

punishments inflicted on Christians, defined as men following a new and

malefic superstition. Suetonius however does not specify the reasons for

the punishment, he just listed the fact together with other abuses put

down by Nero.

Persecution from the 2nd century to Constantine

By

the mid-2nd century, mobs could be found willing to throw stones at

Christians, and they might be mobilized by rival sects. The Persecution in Lyon was preceded by mob violence, including assaults, robberies and stonings (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 5.1.7).

Further state persecutions were desultory until the 3rd century, though Tertullian's Apologeticus of 197 was ostensibly written in defense of persecuted Christians and addressed to Roman governors. The Edict of Septimius Severus familiar in Christian history is doubted by some secular historians to have existed outside Christian martyrology.

There was no empire-wide persecution of Christians until the reign of Decius in the third century.

A decree was issued requiring public sacrifice, a formality equivalent

to a testimonial of allegiance to the Emperor and the established order.

Decius authorized roving commissions

visiting the cities and villages to supervise the execution of the

sacrifices and to deliver written certificates to all citizens who

performed them. Christians were often given opportunities to avoid

further punishment by publicly offering sacrifices or burning incense to Roman gods. Those who refused were charged with impiety

and punished by arrest, imprisonment, torture, and/or executions.

Christians fled to safe havens in the countryside and some purchased

their certificates, called libelli. Several councils held at Carthage debated the extent to which the community should accept these lapsed Christians.

Some early Christians sought out and welcomed martyrdom.

Roman authorities tried hard to avoid Christians because they "goaded,

chided, belittled and insulted the crowds until they demanded their

death." According to Droge and Tabor, "in 185 the proconsul of Asia, Arrius Antoninus,

was approached by a group of Christians demanding to be executed. The

proconsul obliged some of them and then sent the rest away, saying that

if they wanted to kill themselves there was plenty of rope available or

cliffs they could jump off." Such seeking after death is found in Tertullian's Scorpiace or in the letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch but was certainly not the only view of martyrdom in the Christian church. Both Polycarp and Cyprian, bishops in Smyrna and Carthage respectively, attempted to avoid martyrdom.

The Diocletianic Persecution

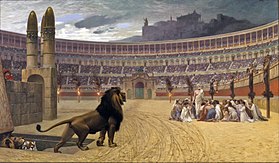

The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer, by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1883).

The persecutions culminated with Diocletian and Galerius at the end of the third and beginning of the 4th century. The Great Persecution

is considered the largest. Beginning with a series of four edicts

banning Christian practices and ordering the imprisonment of Christian

clergy, the persecution intensified until all Christians in the empire

were commanded to sacrifice to the gods or face immediate execution.

This persecution lasted until Constantine I, along with Licinius, legalized Christianity in 313. It was not until Theodosius I in the later 4th century that Christianity would become the State church of the Roman Empire. Between these two events Julian II

temporarily restored the traditional Roman religion and established

broad religious tolerance renewing Pagan and Christian hostilities.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia states that "Ancient, medieval and early modern hagiographers

were inclined to exaggerate the number of martyrs. Since the title of

martyr is the highest title to which a Christian can aspire, this

tendency is natural". Attempts at estimating the numbers involved are

inevitably based on inadequate sources, but one historian of the

persecutions estimates the overall numbers as between 5,500 and 6,500, a number also adopted by later writers including Yuval Noah Harari:

In the 300 years from the crucifixion of Christ to the conversion of Emperor Constantine, polytheistic Roman emperors initiated no more than four general persecutions of Christians. Local administrators and governors incited some anti-Christian violence of their own. Still, if we combine all the victims of all these persecutions, it turns out that in these three centuries, the polytheistic Romans killed no more than a few thousand Christians.

Prohibition and persecution of Paganism in the Roman Empire

The Edict of Milan of 313 finally legalized Christianity, with it gaining governmental privileges and a degree of official approval under Constantine, who granted privileges such as tax exemptions to Christian clergy.

In the period of 313 to 391, both paganism and Christianity were legal

religions, with their respective adherents vying for power in the Roman

Empire. This period of transition is also known as the Constantinian shift. In 380, Theodosius I made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire.

Paganism was tolerated for another 12 years, until 392, when Theodosius

passed legislation prohibiting all pagan worship. Pagan religions from

this point were increasingly persecuted, a process which lasted

throughout the 5th century. The closing of the Neoplatonic Academy by decree of Justinian I in 529 marks a conventional end point of both classical paganism and Late Antiquity, after which most of its scholars fled to more tolerant Sassanid Persia.

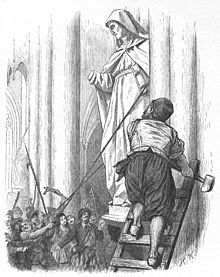

Lay Christians took advantage of these new anti-pagan laws by destroying and plundering the temples.[26] Theologians and prominent ecclesiastics soon followed. One such example is St. Ambrose, Bishop of Milan. When Gratian

became Roman emperor in 375, Ambrose, who was one of his closest

educators, persuaded him to further suppress paganism. The emperor, on

Ambrose's advice, confiscated the property of the pagan temples; seized

the properties of the Vestal Virgins and pagan priests, and removed the

statue of the Goddess of Victory from the Roman Senate.

When Gratian delegated the government of the eastern half of the Roman Empire to Theodosius the Great

in 379, the situation became worse for the Pagans. Theodosius

prohibited all forms of Pagan worship and allowed the temples to be

robbed, plundered, and destroyed by monks and other enterprising

Christians and participated in actions by Christians against major pagan sites.

Pagans openly voiced their resentment in historical works, such as the

writings of Eunapius and Olympiodorus. Some writers blamed the Christian

hegemony for the 410 Sack of Rome, provoking Saint Augustine, a Christian bishop, to respond by writing The City of God,

a seminal Christian text. Christians destroyed almost all such pagan

political literature and threatened to cut off the hands of any copyist

who dared to make new copies of the offending writings.

In the year 416, under Theodosius II, a law was passed to ban Pagans from public employment.[citation needed] All this was done to coerce Pagans to convert to Christianity.

Christianization during the European Middle Ages

Saxons

During the Saxon Wars, the Christian Frankish king Charlemagne

waged war on the pagan Saxons for over 20 years, seeking to

Christianize and rule the Saxons. During this period, the Saxons

repeatedly refused Christianization

and the rule of Charlemagne, and therefore rebelled frequently. In the

year 782 of this period, Charlemagne is recorded as having massacred

4,500 rebel Saxon prisoners in Verden (the Massacre of Verden),

and imposing legislation upon the subjected Saxons that including the

penalty of death for refusing conversion to Christianity or for aiding

pagans who did the same (such as the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae). While rebellions continued to take place even after his death (such as that of the Stellinga),

Charlemagne succeeded in laying the groundwork for the Christianization

of the Saxons, yet was unable to reach the Scandinavians, who remained

pagan.

The Saxons were one of the last groups to be converted by

Christian missionaries. They converted mainly under the threat of death

by Charlemagne, although some concessions to pagan culture were made by

missionaries. The Saxon conversion was so difficult for a number of

reasons including their distance from Rome and the lack of a centralized

polity capable of imposing Christianity from the top down until much

later than other peoples that converted; additionally, their pagan

beliefs were so strongly tied into their culture that conversion

necessarily meant massive cultural change that was hard to accept. Their

sophisticated theology was also a bulwark against an immediate and

complete conversion to Christianity.

The Anglo-Saxon conversion

The conversion of Æthelberht,

king of Kent is the first account of any Christian bretwalda conversion

and is told by the Venerable Bede in his histories of the conversion of

England. In 582 Pope Gregory sent Augustine and 40 companions from

Rome to missionize among the Anglo-Saxons. “They had, by order of the

blessed Pope Gregory, brought interpreters of the nation of the Franks,

and sending to Æthelberht, signified that they were come from Rome, and

brought a joyful message, which most undoubtedly assured to all that

took advantage of it everlasting joys in heaven, and a kingdom that

would never end with the living and true God.”

Æthelberht was not unfamiliar with Christianity because he had a

Christian wife, and Bede says that there was even a church dedicated to

St. Martin nearby. Æthelberht was converted eventually and Augustine

remained in Canterbury.

The Anglo-Saxon conversion in particular was a gradual process

that necessarily included many compromises and syncretism. A famous

letter from Pope Gregory to Mellitus

in June 601, for example, is quoted encouraging the use of pagan

temples by converts to Christianity, though festivals should be held on

significant Christian dates.

Tell Augustine that he should be no means destroy the temples of the gods but rather the idols within those temples. Let him, after he has purified them with holy water, place altars and relics of the saints in them. For, if those temples are well built, they should be converted from the worship of demons to the service of the true God. Thus, seeing that their places of worship are not destroyed, the people will banish error from their hearts and come to places familiar and dear to them in acknowledgement and worship of the true God. Further, since it has been their custom to slaughter oxen in sacrifice, they should receive some solemnity in exchange. Let them therefore, on the day of the dedication of their churches, or on the feast of the martyrs whose relics are preserved in them, build themselves huts around their one-time temples and celebrate the occasion with religious feasting. They will sacrifice and eat the animals not any more as an offering to the devil, but for the glory of God to whom, as the giver of all things, they will give thanks for having been satiated. Thus, if they are not deprived of all exterior joys, they will more easily taste the interior ones. For surely it is impossible to efface all at once everything from their strong minds, just as, when one wishes to reach the top of a mountain, he must climb by stages and step by step, not by leaps and bounds.

— Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (1.30)

Olaf I of Norway, during his attempt to Christianize Norway during the Viking Age, had those under his rule that practiced their indigenous Norse Paganism and refused to Christianize tortured, maimed or executed, including seidmen, who were tied up and thrown to a skerry at low tide to slowly drown. After Olaf I's death, Norway returned to its native paganism.

Northern Crusades

The Christianization of the pagan Balts, Slavs and Finns

was undertaken primarily during the 12th and 13th centuries, in a

series of uncoordinated military campaigns by various German and

Scandinavian kingdoms, and later by the Teutonic Knights

and other orders of warrior-monks, although the paganism of the

inhabitants was used as justification by all of these actors. It

involved the destruction of pagan polities, their subjection to their

Christian conquerors, and frequently the wholesale resettlement of

conquered areas and replacement of the original populations with German

settlers, as in Old Prussia.

Elsewhere, the local populations were subjected to an imported German

overclass. Although revolts were frequent and pagan resistance often

locally successful, the general technological superiority of the

Crusaders, and their support by the Church and rulers throughout

Christendom, eventually resulted in their victory in most cases -

although Lithuania resisted successfully and only converted voluntarily

in the 14th century.

Most of the populations of these regions were converted only with

repeated use of force; in Old Prussia, the tactics employed in the

conquest, and in the subsequent conversion of the territory, resulted in

the death of most of the native population, whose language consequently became extinct.