The

cardinal signs of inflammation include: pain, heat, redness, swelling,

and loss of function. Some of these indicators can be seen here due to

an allergic reaction.

Inflammation (from Latin: inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels,

and molecular mediators. The function of inflammation is to eliminate

the initial cause of cell injury, clear out necrotic cells and tissues

damaged from the original insult and the inflammatory process, and

initiate tissue repair.

The five classical signs of inflammation are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin calor, dolor, rubor, tumor, and functio laesa). Inflammation is a generic response, and therefore it is considered as a mechanism of innate immunity, as compared to adaptive immunity, which is specific for each pathogen.

Too little inflammation could lead to progressive tissue destruction by

the harmful stimulus (e.g. bacteria) and compromise the survival of the

organism. In contrast, chronic inflammation may lead to a host of

diseases, such as hay fever, periodontitis, atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and even cancer (e.g., gallbladder carcinoma). Inflammation is therefore normally closely regulated by the body.

Inflammation can be classified as either acute or chronic. Acute inflammation is the initial response of the body to harmful stimuli and is achieved by the increased movement of plasma and leukocytes (especially granulocytes)

from the blood into the injured tissues. A series of biochemical events

propagates and matures the inflammatory response, involving the local vascular system, the immune system, and various cells within the injured tissue. Prolonged inflammation, known as chronic inflammation, leads to a progressive shift in the type of cells present at the site of inflammation, such as mononuclear cells, and is characterized by simultaneous destruction and healing of the tissue from the inflammatory process.

Inflammation is not a synonym for infection.

Infection describes the interaction between the action of microbial

invasion and the reaction of the body's inflammatory response—the two

components are considered together when discussing an infection, and the

word is used to imply a microbial invasive cause for the observed

inflammatory reaction. Inflammation on the other hand describes purely

the body's immunovascular response, whatever the cause may be. But

because of how often the two are correlated, words ending in the suffix -itis (which refers to inflammation) are sometimes informally described as referring to infection. For example, the word urethritis strictly means only "urethral inflammation", but clinical health care providers usually discuss urethritis as a urethral infection because urethral microbial invasion is the most common cause of urethritis.

It is useful to differentiate inflammation and infection because there are typical situations in pathology and medical diagnosis where inflammation is not driven by microbial invasion – for example, atherosclerosis, trauma, ischemia, and autoimmune diseases including type III hypersensitivity. Conversely, there is pathology where microbial invasion does not cause the classic inflammatory response – for example, parasitosis or eosinophilia.

Causes

Physical:

Psychological:

- Burns

- Frostbite

- Physical injury, blunt or penetrating

- Foreign bodies, including splinters, dirt and debris

- Trauma

- Ionizing radiation

- Infection by pathogens

- Immune reactions due to hypersensitivity

- Stress

Psychological:

- Excitement

Types

|

| Acute | Chronic | |

|---|---|---|

| Causative agent | Bacterial pathogens, injured tissues | Persistent acute inflammation due to non-degradable pathogens, viral infection, persistent foreign bodies, or autoimmune reactions |

| Major cells involved | neutrophils (primarily), basophils (inflammatory response), and eosinophils (response to helminth worms and parasites), mononuclear cells (monocytes, macrophages) | Mononuclear cells (monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells), fibroblasts |

| Primary mediators | Vasoactive amines, eicosanoids | IFN-γ and other cytokines, growth factors, reactive oxygen species, hydrolytic enzymes |

| Onset | Immediate | Delayed |

| Duration | Few days | Up to many months, or years |

| Outcomes | Resolution, abscess formation, chronic inflammation | Tissue destruction, fibrosis, necrosis |

Cardinal signs

| English | Latin | |

|---|---|---|

| Redness | Rubor* | |

| Swelling | Tumor* | |

| Heat | Calor* | |

| Pain | Dolor* | |

| Loss of function | Functio laesa** | |

All the above signs may be observed in specific instances, but no single sign must, as a matter of course, be present.

These are the original, or "cardinal signs" of inflammation.

Functio laesa is an antiquated notion, as it is not unique to inflammation and is a characteristic of many disease states. | ||

Infected ingrown toenail showing the characteristic redness and swelling associated with acute inflammation

Acute inflammation is a short-term process, usually appearing within a

few minutes or hours and begins to cease upon the removal of the

injurious stimulus.

It involves a coordinated and systemic mobilization response locally of

various immune, endocrine and neurological mediators of acute

inflammation. In a normal healthy response, it becomes activated, clears

the pathogen and begins a repair process and then ceases. It is characterized by five cardinal signs:

An acronym that may be used to remember the key symptoms is

"PRISH", for pain, redness, immobility (loss of function), swelling and

heat.

The traditional names for signs of inflammation come from Latin:

The first four (classical signs) were described by Celsus (ca. 30 BC–38 AD), while loss of function was probably added later by Galen. However, the addition of this fifth sign has also been ascribed to Thomas Sydenham and Virchow.

Redness and heat are due to increased blood flow at body core

temperature to the inflamed site; swelling is caused by accumulation of

fluid; pain

is due to the release of chemicals such as bradykinin and histamine

that stimulate nerve endings. Loss of function has multiple causes.

Acute inflammation of the lung (usually caused in response to pneumonia) does not cause pain unless the inflammation involves the parietal pleura, which does have pain-sensitive nerve endings.

Process of acute inflammation

Micrograph showing granulation tissue. H&E stain.

The process of acute inflammation is initiated by resident immune cells already present in the involved tissue, mainly resident macrophages, dendritic cells, histiocytes, Kupffer cells and mast cells. These cells possess surface receptors known as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which recognize (i.e., bind) two subclasses of molecules: pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). PAMPs are compounds that are associated with various pathogens,

but which are distinguishable from host molecules. DAMPs are compounds

that are associated with host-related injury and cell damage.

At the onset of an infection, burn, or other injuries, these

cells undergo activation (one of the PRRs recognize a PAMP or DAMP) and

release inflammatory mediators responsible for the clinical signs of

inflammation. Vasodilation and its resulting increased blood flow causes

the redness (rubor) and increased heat (calor). Increased permeability of the blood vessels results in an exudation (leakage) of plasma proteins and fluid into the tissue (edema), which manifests itself as swelling (tumor). Some of the released mediators such as bradykinin increase the sensitivity to pain (hyperalgesia, dolor). The mediator molecules also alter the blood vessels to permit the migration of leukocytes, mainly neutrophils and macrophages, outside of the blood vessels (extravasation) into the tissue. The neutrophils migrate along a chemotactic gradient created by the local cells to reach the site of injury. The loss of function (functio laesa) is probably the result of a neurological reflex in response to pain.

In addition to cell-derived mediators, several acellular

biochemical cascade systems consisting of preformed plasma proteins act

in parallel to initiate and propagate the inflammatory response. These

include the complement system activated by bacteria and the coagulation and fibrinolysis systems activated by necrosis, e.g. a burn or a trauma.

Acute inflammation may be regarded as the first line of defense

against injury. Acute inflammatory response requires constant

stimulation to be sustained. Inflammatory mediators are short-lived and

are quickly degraded in the tissue. Hence, acute inflammation begins to

cease once the stimulus has been removed.

Vascular component

Vasodilation and increased permeability

As

defined, acute inflammation is an immunovascular response to an

inflammatory stimulus. This means acute inflammation can be broadly

divided into a vascular phase that occurs first, followed by a cellular

phase involving immune cells (more specifically myeloid granulocytes in the acute setting). The vascular component of acute inflammation involves the movement of plasma fluid, containing important proteins such as fibrin and immunoglobulins (antibodies), into inflamed tissue.

Upon contact with PAMPs, tissue macrophages and mastocytes release vasoactive amines such as histamine and serotonin, as well as eicosanoids such as prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4 to remodel the local vasculature. Macrophages and endothelial cells release nitric oxide. These mediators vasodilate and permeabilize the blood vessels, which results in the net distribution of blood plasma from the vessel into the tissue space. The increased collection of fluid into the tissue causes it to swell (edema). This exuded tissue fluid contain various antimicrobial mediators from the plasma such as complement, lysozyme, antibodies,

which can immediately deal damage to microbes, and opsonise the

microbes in preparation for the cellular phase. If the inflammatory

stimulus is a lacerating wound, exuded platelets, coagulants, plasmin and kinins can clot the wounded area and provide haemostasis

in the first instance. These clotting mediators also provide a

structural staging framework at the inflammatory tissue site in the form

of a fibrin lattice – as would construction scaffolding at a construction site – for the purpose of aiding phagocytic debridement and wound repair later on. Some of the exuded tissue fluid is also funnelled by lymphatics to the regional lymph nodes, flushing bacteria along to start the recognition and attack phase of the adaptive immune system.

Acute inflammation is characterized by marked vascular changes, including vasodilation,

increased permeability and increased blood flow, which are induced by

the actions of various inflammatory mediators. Vasodilation occurs first

at the arteriole level, progressing to the capillary

level, and brings about a net increase in the amount of blood present,

causing the redness and heat of inflammation. Increased permeability of

the vessels results in the movement of plasma into the tissues, with resultant stasis

due to the increase in the concentration of the cells within blood – a

condition characterized by enlarged vessels packed with cells. Stasis

allows leukocytes to marginate (move) along the endothelium, a process critical to their recruitment into the tissues. Normal flowing blood prevents this, as the shearing force along the periphery of the vessels moves cells in the blood into the middle of the vessel.

Plasma cascade systems

- The complement system, when activated, creates a cascade of chemical reactions that promotes opsonization, chemotaxis, and agglutination, and produces the MAC.

- The kinin system generates proteins capable of sustaining vasodilation and other physical inflammatory effects.

- The coagulation system or clotting cascade, which forms a protective protein mesh over sites of injury.

- The fibrinolysis system, which acts in opposition to the coagulation system, to counterbalance clotting and generate several other inflammatory mediators.

Plasma-derived mediators

| Name | Produced by | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bradykinin | Kinin system | A vasoactive protein that is able to induce vasodilation, increase vascular permeability, cause smooth muscle contraction, and induce pain. |

| C3 | Complement system | Cleaves to produce C3a and C3b. C3a stimulates histamine release by mast cells, thereby producing vasodilation. C3b is able to bind to bacterial cell walls and act as an opsonin, which marks the invader as a target for phagocytosis. |

| C5a | Complement system | Stimulates histamine release by mast cells, thereby producing vasodilation. It is also able to act as a chemoattractant to direct cells via chemotaxis to the site of inflammation. |

| Factor XII (Hageman Factor) | Liver | A protein that circulates inactively, until activated by collagen, platelets, or exposed basement membranes via conformational change. When activated, it in turn is able to activate three plasma systems involved in inflammation: the kinin system, fibrinolysis system, and coagulation system. |

| Membrane attack complex | Complement system | A complex of the complement proteins C5b, C6, C7, C8, and multiple units of C9. The combination and activation of this range of complement proteins forms the membrane attack complex, which is able to insert into bacterial cell walls and causes cell lysis with ensuing bacterial death. |

| Plasmin | Fibrinolysis system | Able to break down fibrin clots, cleave complement protein C3, and activate Factor XII. |

| Thrombin | Coagulation system | Cleaves the soluble plasma protein fibrinogen to produce insoluble fibrin, which aggregates to form a blood clot. Thrombin can also bind to cells via the PAR1 receptor to trigger several other inflammatory responses, such as production of chemokines and nitric oxide. |

Cellular component

The cellular component involves leukocytes, which normally reside in blood and must move into the inflamed tissue via extravasation to aid in inflammation. Some act as phagocytes, ingesting bacteria, viruses, and cellular debris. Others release enzymatic granules

that damage pathogenic invaders. Leukocytes also release inflammatory

mediators that develop and maintain the inflammatory response. In

general, acute inflammation is mediated by granulocytes, whereas chronic inflammation is mediated by mononuclear cells such as monocytes and lymphocytes.

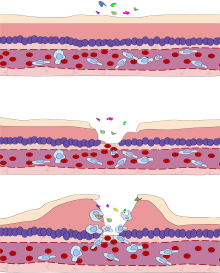

Leukocyte extravasation

Neutrophils

migrate from blood vessels to the infected tissue via chemotaxis, where

they remove pathogens through phagocytosis and degranulation

Inflammation

is a process by which the body's white blood cells and substances they

produce protect us from infection with foreign organisms, such as

bacteria and viruses. The (phagocytes)White blood cells are a

nonspecific immune response, meaning that they attack any foreign

bodies. However, in some diseases, like arthritis, the body's defense

system the immune system triggers an inflammatory response when there

are no foreign invaders to fight off. In these diseases, called

autoimmune diseases, the body's normally protective immune system causes

damage to its own tissues. The body responds as if normal tissues are

infected or somehow abnormal.

Various leukocytes,

particularly neutrophils, are critically involved in the initiation and

maintenance of inflammation. These cells must be able to move to the

site of injury from their usual location in the blood, therefore

mechanisms exist to recruit and direct leukocytes to the appropriate

place. The process of leukocyte movement from the blood to the tissues

through the blood vessels is known as extravasation, and can be broadly divided up into a number of steps:

- Leukocyte margination and endothelial adhesion: The white blood cells within the vessels which are generally centrally located move peripherally towards the walls of the vessels. Activated macrophages in the tissue release cytokines such as IL-1 and TNFα, which in turn leads to production of chemokines that bind to proteoglycans forming gradient in the inflamed tissue and along the endothelial wall. Inflammatory cytokines induce the immediate expression of P-selectin on endothelial cell surfaces and P-selectin binds weakly to carbohydrate ligands on the surface of leukocytes and causes them to "roll" along the endothelial surface as bonds are made and broken. Cytokines released from injured cells induce the expression of E-selectin on endothelial cells, which functions similarly to P-selectin. Cytokines also induce the expression of integrin ligands such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on endothelial cells, which mediate the adhesion and further slow leukocytes down. These weakly bound leukocytes are free to detach if not activated by chemokines produced in injured tissue after signal transduction via respective G protein-coupled receptors that activates integrins on the leukocyte surface for firm adhesion. Such activation increases the affinity of bound integrin receptors for ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on the endothelial cell surface, firmly binding the leukocytes to the endothelium.

- Migration across the endothelium, known as transmigration, via the process of diapedesis: Chemokine gradients stimulate the adhered leukocytes to move between adjacent endothelial cells. The endothelial cells retract and the leukocytes pass through the basement membrane into the surrounding tissue using adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1.

- Movement of leukocytes within the tissue via chemotaxis: Leukocytes reaching the tissue interstitium bind to extracellular matrix proteins via expressed integrins and CD44 to prevent them from leaving the site. A variety of molecules behave as chemoattractants, for example, C3a or C5, and cause the leukocytes to move along a chemotactic gradient towards the source of inflammation.

Phagocytosis

Extravasated neutrophils in the cellular phase come into contact with microbes at the inflamed tissue. Phagocytes express cell-surface endocytic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that have affinity and efficacy against non-specific microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Most PAMPs that bind to endocytic PRRs and initiate phagocytosis are cell wall components, including complex carbohydrates such as mannans and β-glucans, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), peptidoglycans, and surface proteins. Endocytic PRRs on phagocytes reflect these molecular patterns, with C-type lectin receptors binding to mannans and β-glucans, and scavenger receptors binding to LPS.

Upon endocytic PRR binding, actin-myosin cytoskeletal

rearrangement adjacent to the plasma membrane occurs in a way that

endocytoses the plasma membrane containing the PRR-PAMP complex, and the

microbe. Phosphatidylinositol and Vps34-Vps15-Beclin1 signalling pathways have been implicated to traffic the endocytosed phagosome to intracellular lysosomes, where fusion of the phagosome and the lysosome produces a phagolysosome. The reactive oxygen species, superoxides and hypochlorite bleach within the phagolysosomes then kill microbes inside the phagocyte.

Phagocytic efficacy can be enhanced by opsonization. Plasma derived complement C3b

and antibodies that exude into the inflamed tissue during the vascular

phase bind to and coat the microbial antigens. As well as endocytic

PRRs, phagocytes also express opsonin receptors Fc receptor and complement receptor 1

(CR1), which bind to antibodies and C3b, respectively. The

co-stimulation of endocytic PRR and opsonin receptor increases the

efficacy of the phagocytic process, enhancing the lysosomal elimination of the infective agent.

Cell-derived mediators

| Name | Type | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysosome granules | Enzymes | Granulocytes | These cells contain a large variety of enzymes that perform a number of functions. Granules can be classified as either specific or azurophilic depending upon the contents, and are able to break down a number of substances, some of which may be plasma-derived proteins that allow these enzymes to act as inflammatory mediators. |

| Histamine | Monoamine | Mast cells and basophils | Stored in preformed granules, histamine is released in response to a number of stimuli. It causes arteriole dilation, increased venous permeability, and a wide variety of organ-specific effects. |

| IFN-γ | Cytokine | T-cells, NK cells | Antiviral, immunoregulatory, and anti-tumour properties. This interferon was originally called macrophage-activating factor, and is especially important in the maintenance of chronic inflammation. |

| IL-8 | Chemokine | Primarily macrophages | Activation and chemoattraction of neutrophils, with a weak effect on monocytes and eosinophils. |

| Leukotriene B4 | Eicosanoid | Leukocytes, cancer cells | Able to mediate leukocyte adhesion and activation, allowing them to bind to the endothelium and migrate across it. In neutrophils, it is also a potent chemoattractant, and is able to induce the formation of reactive oxygen species and the release of lysosomal enzymes by these cells. |

| LTC4, LTD4 | Eicosanoid | eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages | These three Cysteine-containing leukotrienes contract lung airways, increase micro-vascular permeability, stimulate mucus secretion, and promote eosinophil-based inflammation in the lung, skin, nose, eye, and other tissues. |

| 5-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid | Eicosanoid | leukocytes, cancer cells | Potent stimulator of neutrophil chemotaxis, lysosome enzyme release, and reactive oxygen species formation; monocyte chemotaxis; and with even greater potency eosinophil chemotaxis, lysosome enzyme release, and reactive oxygen species formation. |

| 5-HETE | Eicosanoid | Leukocytes | Metabolic precursor to 5-Oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid, it is a less potent stimulator of neutrophil chemotaxis, lysosome enzyme release, and reactive oxygen species formation; monocyte chemotaxis; and eosinophil chemotaxis, lysosome enzyme release, and reactive oxygen species formation. |

| Prostaglandins | Eicosanoid | Mast cells | A group of lipids that can cause vasodilation, fever, and pain. |

| Nitric oxide | Soluble gas | Macrophages, endothelial cells, some neurons | Potent vasodilator, relaxes smooth muscle, reduces platelet aggregation, aids in leukocyte recruitment, direct antimicrobial activity in high concentrations. |

| TNF-α and IL-1 | Cytokines | Primarily macrophages | Both affect a wide variety of cells to induce many similar inflammatory reactions: fever, production of cytokines, endothelial gene regulation, chemotaxis, leukocyte adherence, activation of fibroblasts. Responsible for the systemic effects of inflammation, such as loss of appetite and increased heart rate. TNF-α inhibits osteoblast differentiation. |

| Tryptase | Enzymes | Mast Cells | This serine protease is believed to be exclusively stored in mast cells and secreted, along with histamine, during mast cell activation. |

Morphologic patterns

Specific

patterns of acute and chronic inflammation are seen during particular

situations that arise in the body, such as when inflammation occurs on

an epithelial surface, or pyogenic bacteria are involved.

- Granulomatous inflammation: Characterised by the formation of granulomas, they are the result of a limited but diverse number of diseases, which include among others tuberculosis, leprosy, sarcoidosis, and syphilis.

- Fibrinous inflammation: Inflammation resulting in a large increase in vascular permeability allows fibrin to pass through the blood vessels. If an appropriate procoagulative stimulus is present, such as cancer cells, a fibrinous exudate is deposited. This is commonly seen in serous cavities, where the conversion of fibrinous exudate into a scar can occur between serous membranes, limiting their function. The deposit sometimes forms a pseudomembrane sheet. During inflammation of the intestine (Pseudomembranous colitis), pseudomembranous tubes can be formed.

- Purulent inflammation: Inflammation resulting in large amount of pus, which consists of neutrophils, dead cells, and fluid. Infection by pyogenic bacteria such as staphylococci is characteristic of this kind of inflammation. Large, localised collections of pus enclosed by surrounding tissues are called abscesses.

- Serous inflammation: Characterised by the copious effusion of non-viscous serous fluid, commonly produced by mesothelial cells of serous membranes, but may be derived from blood plasma. Skin blisters exemplify this pattern of inflammation.

- Ulcerative inflammation: Inflammation occurring near an epithelium can result in the necrotic loss of tissue from the surface, exposing lower layers. The subsequent excavation in the epithelium is known as an ulcer.

Inflammatory disorders

Asthma is considered an inflammatory-mediated disorder. On the right is an inflamed airway due to asthma.

Colitis (inflammation of the colon) caused by Crohn's Disease.

Inflammatory abnormalities are a large group of disorders that

underlie a vast variety of human diseases. The immune system is often

involved with inflammatory disorders, demonstrated in both allergic reactions and some myopathies, with many immune system disorders resulting in abnormal inflammation. Non-immune diseases with causal origins in inflammatory processes include cancer, atherosclerosis, and ischemic heart disease.

Examples of disorders associated with inflammation include:

- Acne vulgaris

- Asthma

- Autoimmune diseases

- Autoinflammatory diseases

- Celiac disease

- Chronic prostatitis

- Colitis

- Diverticulitis

- Glomerulonephritis

- Hidradenitis suppurativa

- Hypersensitivities

- Inflammatory bowel diseases

- Interstitial cystitis

- Lichen planus

- Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

- Mastocytosis

- Otitis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Reperfusion injury

- Rheumatic fever

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Rhinitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Transplant rejection

- Vasculitis

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis, formerly considered a bland lipid storage disease,

actually involves an ongoing inflammatory response. Recent advances in

basic science have established a fundamental role for inflammation in

mediating all stages of this disease from initiation through progression

and, ultimately, the thrombotic complications of atherosclerosis. These

new findings provide important links between risk factors and the

mechanisms of atherogenesis. Clinical studies have shown that this

emerging biology of inflammation in atherosclerosis applies directly to

human patients. Elevation in markers of inflammation predicts outcomes

of patients with acute coronary syndromes, independently of myocardial

damage. In addition, low-grade chronic inflammation, as indicated by

levels of the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein,

prospectively defines risk of atherosclerotic complications, thus

adding to prognostic information provided by traditional risk factors.

Moreover, certain treatments that reduce coronary risk also limit

inflammation. In the case of lipid lowering with statins, this

anti-inflammatory effect does not appear to correlate with reduction in

low-density lipoprotein levels. These new insights into inflammation in

atherosclerosis not only increase our understanding of this disease but

also have practical clinical applications in risk stratification and

targeting of therapy for this scourge of growing worldwide importance.

Allergy

An allergic reaction, formally known as type 1 hypersensitivity,

is the result of an inappropriate immune response triggering

inflammation, vasodilation, and nerve irritation. A common example is hay fever, which is caused by a hypersensitive response by mast cells to allergens. Pre-sensitised mast cells respond by degranulating, releasing vasoactive

chemicals such as histamine. These chemicals propagate an excessive

inflammatory response characterised by blood vessel dilation, production

of pro-inflammatory molecules, cytokine release, and recruitment of

leukocytes. Severe inflammatory response may mature into a systemic response known as anaphylaxis.

Myopathies

Inflammatory

myopathies are caused by the immune system inappropriately attacking

components of muscle, leading to signs of muscle inflammation. They may

occur in conjunction with other immune disorders, such as systemic sclerosis, and include dermatomyositis, polymyositis, and inclusion body myositis.

Leukocyte defects

Due

to the central role of leukocytes in the development and propagation of

inflammation, defects in leukocyte functionality often result in a

decreased capacity for inflammatory defense with subsequent

vulnerability to infection. Dysfunctional leukocytes may be unable to correctly bind to blood vessels due to surface receptor mutations, digest bacteria (Chédiak–Higashi syndrome), or produce microbicides (chronic granulomatous disease). In addition, diseases affecting the bone marrow may result in abnormal or few leukocytes.

Pharmacological

Certain drugs or exogenous chemical compounds are known to affect inflammation. Vitamin A deficiency causes an increase in inflammatory responses, and anti-inflammatory drugs work specifically by inhibiting the enzymes that produce inflammatory eicosanoids.

Certain illicit drugs such as cocaine and ecstasy may exert some of

their detrimental effects by activating transcription factors intimately

involved with inflammation (e.g. NF-κB).

Cancer

Inflammation orchestrates the microenvironment around tumours, contributing to proliferation, survival and migration. Cancer cells use selectins, chemokines and their receptors for invasion, migration and metastasis. On the other hand, many cells of the immune system contribute to cancer immunology, suppressing cancer.

Molecular intersection between receptors of steroid hormones, which have

important effects on cellular development, and transcription factors

that play key roles in inflammation, such as NF-κB, may mediate some of the most critical effects of inflammatory stimuli on cancer cells.

This capacity of a mediator of inflammation to influence the effects of

steroid hormones in cells, is very likely to affect carcinogenesis on

the one hand; on the other hand, due to the modular nature of many

steroid hormone receptors, this interaction may offer ways to interfere

with cancer progression, through targeting of a specific protein domain

in a specific cell type. Such an approach may limit side effects that

are unrelated to the tumor of interest, and may help preserve vital

homeostatic functions and developmental processes in the organism.

According to a review of 2009, recent data suggests that

cancer-related inflammation (CRI) may lead to accumulation of random

genetic alterations in cancer cells.

Importance of inflammation in cancer

In 1863, Rudolf Virchow hypothesized that the origin of cancer was at sites of chronic inflammation. At present, chronic inflammation is estimated to contribute to approximately 15% to 25% of human cancers.

Mediators and DNA damage in cancer

An inflammatory mediator is a messenger that acts on blood vessels and/or cells to promote an inflammatory response. Inflammatory mediators that contribute to neoplasia include prostaglandins, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-15 and chemokines such as IL-8 and GRO-alpha. These inflammatory mediators, and others, orchestrate an environment that fosters proliferation and survival.

Inflammation also causes DNA damages due to the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by various intracellular inflammatory mediators. In addition, leukocytes and other phagocytic cells attracted to the site of inflammation induce DNA damages in proliferating cells through their generation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). ROS and RNS are normally produced by these cells to fight infection. ROS, alone, cause more than 20 types of DNA damage. Oxidative DNA damages cause both mutations and epigenetic alterations. RNS also cause mutagenic DNA damages.

A normal cell may undergo carcinogenesis

to become a cancer cell if it is frequently subjected to DNA damage

during long periods of chronic inflammation. DNA damages may cause

genetic mutations due to inaccurate repair. In addition, mistakes in the DNA repair process may cause epigenetic alterations.

Mutations and epigenetic alterations that are replicated and provide a

selective advantage during somatic cell proliferation may be

carcinogenic.

Genome-wide analyses of human cancer tissues reveal that a single typical cancer cell may possess roughly 100 mutations in coding regions, 10-20 of which are “driver mutations” that contribute to cancer development. However, chronic inflammation also causes epigenetic changes such as DNA methylations,

that are often more common than mutations. Typically, several hundreds

to thousands of genes are methylated in a cancer cell. Sites of oxidative damage in chromatin can recruit complexes that contain DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), a histone deacetylase (SIRT1), and a histone methyltransferase (EZH2), and thus induce DNA methylation. DNA methylation of a CpG island in a promoter region may cause silencing of its downstream gene (see CpG site and regulation of transcription in cancer). DNA repair genes, in particular, are frequently inactivated by methylation in various cancers (see hypermethylation of DNA repair genes in cancer). A 2018 report

evaluated the relative importance of mutations and epigenetic

alterations in progression to two different types of cancer. This

report showed that epigenetic alterations were much more important than

mutations in generating gastric cancers (associated with inflammation).

However, mutations and epigenetic alterations were of roughly equal

importance in generating esophageal squamous cell cancers (associated

with tobacco chemicals and acetaldehyde, a product of alcohol metabolism).

HIV and AIDS

It

has long been recognized that infection with HIV is characterized not

only by development of profound immunodeficiency but also by sustained

inflammation and immune activation.

A substantial body of evidence implicates chronic inflammation as a

critical driver of immune dysfunction, premature appearance of

aging-related diseases, and immune deficiency. Many now regard HIV infection not only as an evolving virus-induced immunodeficiency but also as chronic inflammatory disease. Even after the introduction of effective antiretroviral therapy

(ART) and effective suppression of viremia in HIV-infected individuals,

chronic inflammation persists. Animal studies also support the

relationship between immune activation and progressive cellular immune

deficiency: SIVsm infection of its natural nonhuman primate hosts, the sooty mangabey, causes high-level viral replication but limited evidence of disease.

This lack of pathogenicity is accompanied by a lack of inflammation,

immune activation and cellular proliferation. In sharp contrast,

experimental SIVsm infection of rhesus macaque produces immune activation and AIDS-like disease with many parallels to human HIV infection.

Delineating how CD4 T cells are depleted and how chronic

inflammation and immune activation are induced lies at the heart of

understanding HIV pathogenesis––one of the top priorities for HIV

research by the Office of AIDS Research, National Institutes of Health. Recent studies demonstrated that caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis, a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death, drives CD4 T-cell depletion and inflammation by HIV. These are the two signature events that propel HIV disease progression to AIDS.

Pyroptosis appears to create a pathogenic vicious cycle in which dying

CD4 T cells and other immune cells (including macrophages and

neutrophils) release inflammatory signals that recruit more cells into

the infected lymphoid tissues to die. The feed-forward nature of this

inflammatory response produces chronic inflammation and tissue injury.

Identifying pyroptosis as the predominant mechanism that causes CD4

T-cell depletion and chronic inflammation, provides novel therapeutic

opportunities, namely caspase-1 which controls the pyroptotic pathway.

In this regard, pyroptosis of CD4 T cells and secretion of

pro-inflmammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 can be blocked in HIV-infected human lymphoid tissues by addition of the caspase-1 inhibitor VX-765, which has already proven to be safe and well tolerated in phase II human clinical trials.

These findings could propel development of an entirely new class of

“anti-AIDS” therapies that act by targeting the host rather than the

virus. Such agents would almost certainly be used in combination with

ART. By promoting “tolerance” of the virus instead of suppressing its

replication, VX-765 or related drugs may mimic the evolutionary

solutions occurring in multiple monkey hosts (e.g. the sooty mangabey)

infected with species-specific lentiviruses that have led to a lack of

disease, no decline in CD4 T-cell counts, and no chronic inflammation.

Resolution of inflammation

The

inflammatory response must be actively terminated when no longer needed

to prevent unnecessary "bystander" damage to tissues.

Failure to do so results in chronic inflammation, and cellular

destruction. Resolution of inflammation occurs by different mechanisms

in different tissues.

Mechanisms that serve to terminate inflammation include:

- Short half-life of inflammatory mediators in vivo.

- Production and release of transforming growth factor (TGF) beta from macrophages

- Production and release of interleukin 10 (IL-10)

- Production of anti-inflammatory specialized proresolving mediators, i.e. lipoxins, resolvins, maresins, and neuroprotectins

- Downregulation of pro-inflammatory molecules, such as leukotrienes.

- Upregulation of anti-inflammatory molecules such as the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist or the soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)

- Apoptosis of pro-inflammatory cells

- Desensitization of receptors.

- Increased survival of cells in regions of inflammation due to their interaction with the extracellular matrix (ECM)

- Downregulation of receptor activity by high concentrations of ligands

- Cleavage of chemokines by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) might lead to production of anti-inflammatory factors.

| “ | Acute inflammation normally resolves by mechanisms that have remained somewhat elusive. Emerging evidence now suggests that an active, coordinated program of resolution initiates in the first few hours after an inflammatory response begins. After entering tissues, granulocytes promote the switch of arachidonic acid–derived prostaglandins and leukotrienes to lipoxins, which initiate the termination sequence. Neutrophil recruitment thus ceases and programmed death by apoptosis is engaged. These events coincide with the biosynthesis, from omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, of resolvins and protectins, which critically shorten the period of neutrophil infiltration by initiating apoptosis. As a consequence, apoptotic neutrophils undergo phagocytosis by macrophages, leading to neutrophil clearance and release of anti-inflammatory and reparative cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β1. The anti-inflammatory program ends with the departure of macrophages through the lymphatics. | ” |

| — Charles Serhan | ||

Connection to depression

There is evidence for a link between inflammation and depression.

Inflammatory processes can be triggered by negative cognitions or their

consequences, such as stress, violence, or deprivation. Thus, negative

cognitions can cause inflammation that can, in turn, lead to depression.

In addition there is increasing evidence that inflammation can cause

depression because of the increase of cytokines, setting the brain into a

"sickness mode".

Classical symptoms of being physically sick like lethargy show a large

overlap in behaviors that characterize depression. Levels of cytokines

tend to increase sharply during the depressive episodes of people with

bipolar disorder and drop off during remission.

Furthermore, it has been shown in clinical trials that

anti-inflammatory medicines taken in addition to antidepressants not

only significantly improves symptoms but also increases the proportion

of subjects positively responding to treatment.

Inflammations that lead to serious depression could be caused by common

infections such as those caused by a virus, bacteria or even parasites.

Systemic effects

An infectious organism can escape the confines of the immediate tissue via the circulatory system or lymphatic system,

where it may spread to other parts of the body. If an organism is not

contained by the actions of acute inflammation it may gain access to the

lymphatic system via nearby lymph vessels. An infection of the lymph vessels is known as lymphangitis, and infection of a lymph node is known as lymphadenitis.

When lymph nodes cannot destroy all pathogens, the infection spreads

further. A pathogen can gain access to the bloodstream through lymphatic

drainage into the circulatory system.

When inflammation overwhelms the host, systemic inflammatory response syndrome is diagnosed. When it is due to infection, the term sepsis is applied, with the terms bacteremia being applied specifically for bacterial sepsis and viremia specifically to viral sepsis. Vasodilation and organ dysfunction are serious problems associated with widespread infection that may lead to septic shock and death.

Acute-phase proteins

Inflammation also induces high systemic levels of acute-phase proteins. In acute inflammation, these proteins prove beneficial; however, in chronic inflammation they can contribute to amyloidosis. These proteins include C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A, and serum amyloid P, which cause a range of systemic effects including:

- Fever

- Increased blood pressure

- Decreased sweating

- Malaise

- Loss of appetite

- Somnolence

Leukocyte numbers

Inflammation often affects the numbers of leukocytes present in the body:

- Leukocytosis is often seen during inflammation induced by infection, where it results in a large increase in the amount of leukocytes in the blood, especially immature cells. Leukocyte numbers usually increase to between 15 000 and 20 000 cells per microliter, but extreme cases can see it approach 100 000 cells per microliter. Bacterial infection usually results in an increase of neutrophils, creating neutrophilia, whereas diseases such as asthma, hay fever, and parasite infestation result in an increase in eosinophils, creating eosinophilia.

- Leukopenia can be induced by certain infections and diseases, including viral infection, Rickettsia infection, some protozoa, tuberculosis, and some cancers.

Systemic inflammation and obesity

With the discovery of interleukins (IL), the concept of systemic inflammation

developed. Although the processes involved are identical to tissue

inflammation, systemic inflammation is not confined to a particular

tissue but involves the endothelium and other organ systems.

Chronic inflammation is widely observed in obesity. Obese people commonly have many elevated markers of inflammation, including:

Low-grade chronic inflammation is characterized by a two- to

threefold increase in the systemic concentrations of cytokines such as

TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP. Waist circumference correlates significantly with systemic inflammatory response.

Loss of white adipose tissue reduces levels of inflammation markers. The association of systemic inflammation with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, and with atherosclerosis is under preliminary research, although rigorous clinical trials have not been conducted to confirm such relationships.

C-reactive protein (CRP) is generated at a higher level in obese people, and may increase the risk for cardiovascular diseases.

Outcomes

Scars present on the skin, evidence of fibrosis and healing of a wound

The outcome in a particular circumstance will be determined by the

tissue in which the injury has occurred and the injurious agent that is

causing it. Here are the possible outcomes to inflammation:

- Resolution

The complete restoration of the inflamed tissue back to a normal status. Inflammatory measures such as vasodilation, chemical production, and leukocyte infiltration cease, and damaged parenchymal cells regenerate. In situations where limited or short-lived inflammation has occurred this is usually the outcome. - Fibrosis

Large amounts of tissue destruction, or damage in tissues unable to regenerate, cannot be regenerated completely by the body. Fibrous scarring occurs in these areas of damage, forming a scar composed primarily of collagen. The scar will not contain any specialized structures, such as parenchymal cells, hence functional impairment may occur. - Abscess formation

A cavity is formed containing pus, an opaque liquid containing dead white blood cells and bacteria with general debris from destroyed cells. - Chronic inflammation

In acute inflammation, if the injurious agent persists then chronic inflammation will ensue. This process, marked by inflammation lasting many days, months or even years, may lead to the formation of a chronic wound. Chronic inflammation is characterised by the dominating presence of macrophages in the injured tissue. These cells are powerful defensive agents of the body, but the toxins they release (including reactive oxygen species) are injurious to the organism's own tissues as well as invading agents. As a consequence, chronic inflammation is almost always accompanied by tissue destruction.

Diet and inflammation

The

Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) is a score (number) that describes the

potential of diet to modulate systemic inflammation within the body.

As stated chronic inflammation is linked to most chronic diseases

including arthritis, many types of cancer, cardiovascular diseases,

inflammatory bowel diseases, and diabetes.

Exercise and inflammation

Exercise-induced acute inflammation

Acute inflammation of the muscle cells, as understood in exercise physiology, can result after induced eccentric and concentric

muscle training. Participation in eccentric training and conditioning,

including resistance training and activities that emphasize eccentric

lengthening of the muscle

including downhill running on a moderate to high incline can result in

considerable soreness within 24 to 48 hours, even though blood lactate levels, previously thought to cause muscle soreness, were much higher with level running. This delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) results from structural damage to the contractile filaments and z-disks, which has been noted especially in marathon runners whose muscle fibers revealed remarkable damage to the muscle fibers after both training and marathon competition.

The onset and timing of this gradient damage to the muscle parallels

the degree of muscle soreness experienced by the runners.

Z-disks are the point of contact for the contractile proteins.

They provide structural support for transmission of force when muscle

fibers are activated to shorten. However, in marathon runners and those

who subscribe to the overload principle to enhance their muscles, show

moderate Z-disk streaming and major disruption of thick and thin

filaments in parallel groups of sarcomeres as a result of the force of

eccentric actions or stretching of tightened muscle fibers.

This disruption of muscle fibers triggers white blood cells to

increase following induced muscle soreness, leading to the inflammatory

response observation from induced muscle soreness. Elevations in plasma

enzymes, myoglobinemia, and abnormal muscle histology and ultrastructure

are concluded to be associated with inflammatory response. High tension

in the contractile-elastic system of muscle results in structural

damage to the muscle fiber and plasmalemma and its epimysium,

perimysium, and/or endomysium. The mysium damage disrupts calcium

homeostasis in injured fibers and fiber bundles, resulting in necrosis

that peaks about 48 hours after exercise. The products of macrophage

activity and intracellular contents (such as histamines, kinins, and K+)

accumulate outside cells. These substances then stimulate free nerve

endings in the muscle; a process that appears accentuated by eccentric

exercise, in which large forces are distributed over a relatively small

cross-sectional area of the muscle.

Post-inflammatory muscle growth and repair

There is a known relationship between inflammation and muscle growth. For instance, high doses of anti-inflammatory medicines (e.g., NSAIDs) are able to blunt muscle growth.

Cold therapy has been shown to negatively affect muscle growth as well.

Reducing inflammation results in decreased macrophage activity and

lower levels of IGF-1 Acute effects of cold therapy on training adaptations show reduced satellite cell proliferation. Long term effects include less muscular hypertrophy and an altered cell structure of muscle fibers.

It has been further theorized that the acute localized

inflammatory responses to muscular contraction during exercise, as

described above, are a necessary precursor to muscle growth.

As a response to muscular contractions, the acute inflammatory response

initiates the breakdown and removal of damaged muscle tissue. Muscles can synthesize cytokines in response to contractions, such that the cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), TNF-α, and IL-6 are expressed in skeletal muscle up to 5 days after exercise.

In particular, the increase in levels of IL-6 (interleukin 6), a myokine, can reach up to one hundred times that of resting levels. Depending on volume, intensity, and other training factors, the IL-6 increase associated with

training initiates about 4 hours after resistance training and remains elevated for up to 24 hours.

These acute increases in cytokines, as a response to muscle

contractions, help initiate the process of muscle repair and growth by

activating satellite cells within the inflamed muscle. Satellite cells are crucial for skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise.

They contribute to hypertrophy by providing new myonuclei and repair

damaged segments of mature myofibers for successful regeneration

following injury- or exercise-induced muscle damage; high-level powerlifters can have up to 100% more satellite cells than untrained controls.

A rapid and transient localization of the IL-6 receptor and

increased IL-6 expression occurs in satellite cells following

contractions. IL-6 has been shown to mediate

hypertrophic muscle growth both in vitro and in vivo. Unaccustomed exercise can increase IL-6 by up to sixfold at 5 hours post-exercise and threefold 8 days after exercise. Also telling is the fact that NSAIDs can decrease satellite cell response to exercise, thereby reducing exercise-induced protein synthesis.

The increase in cytokines (myokines) after resistance exercise coincides with the decrease in levels of myostatin, a protein that inhibits muscle differentiation and growth.

The cytokine response to resistance exercise and moderate-intensity

running occur differently, with the latter causing a more prolonged

response, especially at the 12–24 hour mark.

Developing research has demonstrated that many of the benefits of

exercise are mediated through the role of skeletal muscle as an

endocrine organ. That is, contracting muscles release multiple

substances known as myokines,

including but not limited to those cited in the above description,

which promote the growth of new tissue, tissue repair, and various

anti-inflammatory functions, which in turn reduce the risk of developing

various inflammatory diseases. The new view that muscle is an endocrine

organ is transforming our understanding of exercise physiology and with

it, of the role of inflammation in adaptation to stress.

Chronic inflammation and muscle loss

Both

chronic and extreme inflammation are associated with disruptions of

anabolic signals initiating muscle growth. Chronic inflammation has been

implicated as part of the cause of the muscle loss that occurs with aging.

Increased protein levels of myostatin have been described in patients

with diseases characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation. Increased levels of TNF-α can suppress the AKT/mTOR pathway, a crucial pathway for regulating skeletal muscle hypertrophy, thereby increasing muscle catabolism. Cytokines may antagonize the anabolic effects of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). In the case of sepsis, an extreme whole body inflammatory state, the synthesis of both myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic proteins are inhibited, with the inhibition taking place preferentially in fast-twitch muscle fibers. Sepsis is also able to prevent leucine from stimulating muscle protein synthesis. In animal models, when inflammation is created, mTOR loses its ability to be stimulated by muscle growth.

Exercise as a treatment for inflammation

Regular physical activity is reported to decrease markers of inflammation,

although the correlation is imperfect and seems to reveal differing

results contingent upon training intensity. For instance, while baseline

measurements of circulating inflammatory markers do not seem to differ

greatly between healthy trained and untrained adults, long-term training may help reduce chronic low-grade inflammation. On the other hand, levels of the anti-inflammatory myokine IL-6 (interleukin 6)

remained elevated longer into the recovery period following an acute

bout of exercise in patients with inflammatory diseases, relative to the

recovery of healthy controls.

It may well be that low-intensity training can reduce resting

pro-inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6), while moderate-intensity training

has milder and less-established anti-inflammatory benefits. There is a strong relationship between exhaustive exercise and chronic low-grade inflammation.

Marathon running may enhance IL-6 levels as much as 100 times over

normal and increases total leuckocyte count and neturophil mobilization.

Regarding the above, IL-6 had previously been classified as a

proinflammatory cytokine. Therefore, it was first thought that the

exercise-induced IL-6 response was related to muscle damage.

However, it has become evident that eccentric exercise is not

associated with a larger increase in plasma IL-6 than exercise involving

concentric “nondamaging” muscle contractions. This finding clearly

demonstrates that muscle damage is not required to provoke an increase

in plasma IL-6 during exercise. As a matter of fact, eccentric exercise

may result in a delayed peak and a much slower decrease of plasma IL-6

during recovery.

Recent work has shown that both upstream and downstream

signalling pathways for IL-6 differ markedly between myocytes and

macrophages. It appears that unlike IL-6 signalling in macrophages,

which is dependent upon activation of the NFκB signalling pathway,

intramuscular IL-6 expression is regulated by a network of signalling

cascades, including the Ca2+/NFAT and glycogen/p38 MAPK pathways. Thus,

when IL-6 is signalling in monocytes or macrophages, it creates a

pro-inflammatory response, whereas IL-6 activation and signalling in

muscle is totally independent of a preceding TNF-response or NFκB

activation, and is anti-inflammatory.

Several studies show that markers of inflammation are reduced

following longer-term behavioural changes involving both reduced energy

intake and a regular program of increased physical activity, and that,

in particular, IL-6 was miscast as an inflammatory marker. For example,

the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-6 have been demonstrated by IL-6

stimulating the production of the classical anti-inflammatory cytokines

IL-1ra and IL-10.

As such, individuals pursuing exercise as a means to treat the causal

factors underlying chronic inflammation are pursuing a course of action

strongly supported by current research, as an inactive lifestyle is

strongly associated with the development and progression of multiple

inflammatory diseases. Note that cautions regarding over-exertion may

apply in certain cases, as discussed above, though this concern rarely

applies to the general population.

Signal-to-noise theory

Given

that localized acute inflammation is a necessary component for muscle

growth, and that chronic low-grade inflammation is associated with a

disruption of anabolic signals initiating muscle growth, it has been

theorized that a signal-to-noise model may best describe the relationship between inflammation and muscle growth.

By keeping the "noise" of chronic inflammation to a minimum, the

localized acute inflammatory response signals a stronger anabolic

response than could be achieved with higher levels of chronic

inflammation.