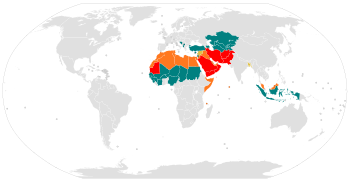

The

role of Islam or religion in the Muslim-majority countries as outlined

in the constitutions, including Islamic and secular states

Islamic state

State religion

Unclear / No declaration

Secular state

Secularism

has been a controversial concept in Islamic political thought, owing in

part to historical factors and in part to the ambiguity of the concept

itself.

In the Muslim world, the notion has acquired strong negative

connotations due to its association with removal of Islamic influences

from the legal and political spheres under foreign colonial domination,

as well as attempts to restrict public religious expression by some

secularist nation states.

Thus, secularism has often been perceived as a foreign ideology imposed

by invaders and perpetuated by post-colonial ruling elites, and understood as equivalent to irreligion or antireligion.

Some Islamic reformists like Ali Abdel Raziq and Mahmoud Mohammed Taha have advocated a secular state in the sense of political order that does not impose any single interpretation of sharia on the nation.

A number of Islamic and academic authors have argued that there is no

religious reason that would prevent Muslims from accepting secularism in

the sense of state neutrality toward religion. Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im

has argued that a secular state built on constitutionalism, human

rights and full citizenship is more consistent with Islamic history than

modern visions of an Islamic state. Proponents of Islamism (political Islam)

reject secularist views that would limit Islam to matters of personal

belief and instead advocate for a return to Islamic law and Islamic

political authority.

A number of pre-modern polities in the Islamic world demonstrated

some level of separation between religious and political authority,

even if they did not adhere to the modern concept of a state with no

official religion or religion-based laws.

Today, some Muslim-majority countries define themselves as or are

regarded as secular, and many of them have a dual system in which

Muslims can bring familial and financial disputes to sharia

courts. The exact jurisdiction of these courts varies from country to

country, but usually includes marriage, divorce, inheritance, and

guardianship.

Definition

Secularism is an ambiguous concept that could be understood to refer

to anticlericalism, atheism, state neutrality toward religion, the

separation of religion from state, banishment of religious symbols from

the public sphere, or disestablishment (separation of church and state),

although the latter meaning would not be relevant in the Islamic

context, since Islam has no institution corresponding to this sense of

"church".

There is no word in Arabic, Persian or Turkish corresponding

exactly to the English term "secularism". In Arabic, two words are

commonly used as translations: ʿilmānīyah (from the Arabic word for science) and ʿalmanīyah. The latter term, which first appeared at the end of the nineteenth century in the dictionary Muhit al-Muhit written by the Christian Lebanese scholar Butrus al-Bustani, was apparently derived from the Arabic word for "world". Arab activists concerned about marginalization of religious practices and beliefs have sometimes used the term la diniyah (non-religion). In Persian, one finds the loan word sekularizm, while in Turkish laiklik comes from the French laïcité.

Overview

The

concept of secularism was imported along with many of the ideas of

post-enlightenment modernity from Europe into the Muslim world, namely

Middle East and North Africa. Among Muslim intellectuals, the early

debate on secularism centered mainly on the relationship between

religion and state, and how this relationship was related to European

successes in science, technology and governance.

In the debate on the relationship between religion and state,

(in)separability of religious and political authorities in the Islamic

world, or status of the Caliph, was one of the biggest issues.

John L. Esposito,

a professor of international affairs and Islamic studies, points out:

"the post-independent period witnessed the emergence of modern Muslim

states whose pattern of development was heavily influenced by and

indebted to Western secular paradigms or models. Saudi Arabia and Turkey

reflected the two polar positions. [...] The majority of Muslim states

chose a middle ground in nation building, borrowing heavily from the

West and relying on foreign advisers and Western-educated elites."

Esposito also argues that in many modern Muslim countries the

role of Islam in state and society as a source of legitimation for

rulers, state, and government institutions was greatly decreased though

the separation of religion and politics was not total. However while

most Muslim governments replaced Islamic law with legal systems inspired

by western secular codes, Muslim family law (marriage, divorce, and

inheritance) remained in force.

However, many Muslims argue that, unlike Christianity, Islam does

not separate religion from the state and many Muslims around the world

welcome a significant role for Islam in their countries' political life.

It is apolitical Islam, not political Islam, that requires explanation

and that is an historical fluke of the "shortlived heyday of secular

Arab nationalism between 1945 and 1970."

Furthermore, the resurgence of Islam, beginning with the Iranian

revolution of 1978-9, defied the illusions of advocates of

secularization theory. The resurgence of Islam in politics in the most

modernizing of Muslim countries, such as Egypt, Algeria and Turkey,

betrayed expectations of those who believed religion should be at the

margins not the center of public life. Furthermore, in most cases, it

was not rural but urban phenomena, and its leaders and supporters were

educated professionals.

From a more historical perspective, scholar Olivier Roy

argues that "a defacto separation between political power" of sultans

and emirs and religious power of the caliph was "created and

institutionalized ... as early as the end of the first century of the hegira"

and what has been lacking in the Muslim world is "political thought

regarding the autonomy of this space." No positive law was developed

outside of sharia. The sovereign's religious function was to defend the

Islamic community against its enemies, institute the sharia, ensure the public good (maslaha). The state was an instrument to enable Muslims to live as good Muslims and Muslims were to obey the sultan if he did so. The legitimacy of the ruler was "symbolized by the right to coin money and to have the Friday prayer (Jumu'ah khutba) said in his name."

History

Early history

Ira M. Lapidus,

an Emeritus Professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic History at The

University of California at Berkeley, notes that religious and political

power was united while the Prophet Muhammad was leading the ummah, resulting in a non-secular state. But Lapidus states that by the 10th century, some governments in the Muslim world

had developed an effective separation of religion and politics, due to

political control passing "into the hands of generals, administrators,

governors, and local provincial lords; the Caliphs had lost all

effective political power". These governments were still officially

Islamic and committed to the religion, but religious authorities had

developed their own hierarchies and bases of power separate from the

political institutions governing them:

In the same period, religious communities developed independently of the states or empires that ruled them. The ulama regulated local communal and religious life by serving as judges, administrators, teachers, and religious advisers to Muslims. The religious elites were organized according to religious affiliation into Sunni schools of law, Shi'ite sects, or Sufi tariqas. [...] In the wide range of matters arising from the Shari'a - the Muslim law - the 'ulama' of the schools formed a local administrative and social elite whose authority was based upon religion.

Lapidus argues that the religious and political aspects of Muslim

communal life came to be separated by Arab rebellions against the

Caliphate, the emergence of religious activity independent of the actual

authority of the Caliphs, and the emergence of the Hanbali school of law.

The Umayyad caliphate

was seen as a secular state by many Muslims at the time, some of whom

disapproved of the lack of integration of politics and religion. This

perception was offset by a steady stream of wars that aimed to expand

Muslim rule past the caliphate's borders.

In early Islamic philosophy, Averroes presented an argument in The Decisive Treatise providing a justification for the emancipation of science and philosophy from official Ash'ari theology. Because of this, some consider Averroism a precursor to modern secularism.

Others argue that this reflects an incorrect view of his philosophy,

stripped of its inherent Islamic dimensions by European philosophers.

Modern history

Many of the early supporters of Secularist principles in Middle Eastern countries were Baathist and non-Muslim Arabs, seeking a solution to a multi-confessional population and an ongoing drive to modernism.

Many Islamic modernist thinkers

argued against the inseparability of religious and political

authorities in the Islamic world, and described the system of separation

between religion and state within their ideal Islamic world.

Muhammad ʿAbduh, a prominent Muslim modernist thinker, claimed in his book "Al-Idtihad fi Al-Nasraniyya wa Al-Islam"

that no one had exclusive religious authority in the Islamic world. He

argued that the Caliph did not represent religious authority, because he

was not infallible nor was the Caliph the person whom the revelation

was given to; therefore, according to Abduh, the Caliph and other

Muslims are equal. ʿAbduh argued that the Caliph should have the respect

of the umma but not rule it; the unity of the umma is a moral unity

which does not prevent its division into national states.

Abdel Rahman Al-Kawakibi, in his book "Taba'i' Al-Istibdad (The

Characteristics of Tyranny)", discussed the relationship between

religion and despotism,

arguing that "while most religions tried to enslave the people to the

holders of religious office who exploited them, the original Islam was

built on foundations of political freedom standing between democracy and

aristocracy."

Al-Kawakibi suggested that people can achieve a non-religious national

unity, saying:"Let us take care of our lives in this world and let the

religions rule in the next world."

Moreover, in his second book "Umm Al-Qura (The Mother of Villages)" his

most explicit statement with regard to the question of religion and

state appeared in an appendix to the book, where he presented a dialogue

between the Muslim scholar from India and an amir. The amir expressed

his opinion that "religion is one thing and the government is another

... The administration of religion and the administration of the

government were never united in Islam."

Rashid Rida's

thoughts about the separation of religion and state had some

similarities with ʿAbduh and Al-Kawakibi. According to the scholar,

Eliezer Tauber:

He was of the opinion that according to Islam 'the rule over the nation is in its own hands ... and its government is a sort of a republic. The caliph has no superiority in law over the lowest of the congregation; he only executes the religious law and the will of the nation.' And he added: 'For the Muslims, the caliph is not infallible (ma'sum) and not the source of revelation.' And therefore, 'the nation has the right to depose the imam-caliph, if it finds a reason for doing so'.

What is unique in Rida's thought is that he provided details of his

ideas about the future Arab empire in a document, which he called the

"General Organic Law of the Arab Empire". Rida argued that the general

administrative policy of the future empire would be managed by a

president, a council of deputies to be elected from the entire empire,

and a council of ministers to be chosen by the president from among the

deputies. There, the caliph must recognize the 'General Organic Law' and

abide by it. He would manage all the religious matters of the empire.

Rida's ideal Islamic empire would be administered in practice by a

president, while the caliph would administer only religious affairs and

would be obliged to recognize the organic law of the empire and abide by

it.

As seen above, these arguments about separability of religious

and political authorities in the Islamic world were greatly connected

with the presence of the Caliphate.

Therefore, the abolishment of the Caliphate by Turkish government in

1924 had considerable influence on such arguments among Muslim

intellectuals.

The most controversial work is that of Ali Abd al-Raziq, an Islamic Scholar and Shari’a judge who caused a sensation with his work "Islam and the Foundations of Governance (Al-Islam Wa Usul Al-Hukm)" in 1925. He argued that there were no clear evidence in the Quran and the hadith,

which justify a common assumption: to accept the authority of the

caliph is an obligation. Furthermore, he claimed that it was not even

necessary that the ummah

should be politically united and religion has nothing to do with one

form of government rather than another. He argued that there is nothing

in Islam which forbids Muslims to destroy their old political system and

build a new one on the basis or the newest conceptions of the human

spirit and the experience of nations.

This publication caused a fierce debate especially as he recommended

that religion can be separated from government and politics. He was

later removed from his position. Rosenthall commented on him saying

"we meet for the first time a consistent, unequivocal theoretical assertion of the purely and exclusively religious character of Islam".

Taha Hussein, an Egyptian writer, was also an advocate for the separation of religion and politics from a viewpoint of Egyptian nationalism. Hussein believed that Egypt always had been part of Western civilization

and that Egypt had its renaissance in the nineteenth century and had

re-Europeanized itself. For him, the distinguishing mark of the modern

world is that it has brought about a virtual separation of religion and

civilization, each in its own sphere. It is therefore quite possible to

take the bases of civilization from Europe without its religion,

Christianity. Moreover, he believed that it is easier for Muslims than

for Christian, since Islam has no priesthood, and so there has grown up

no vested interest in the control of religion over society.

Secular feminism

Azza

Karam (1998:13) describes secular feminists as follows: "Secular

feminists firmly believe in grounding their discourse outside the realm

of any religion, whether Muslim or Christian, and placing it, instead

within the international human rights discourse. They do not ‘waste

their time’ attempting to harmonize religious discourses with the

concept and declarations pertinent to human rights. To them religion is

respected as a private matter for each individual, but it is totally

rejected as a basis from which to formulate any agenda on women’s

emancipation. By so doing, they avoid being caught up in interminable

debates on the position of women with religion."

Generally, secular feminist activists call for total equality between

the sexes, attempt to ground their ideas on women’s rights outside

religious frameworks, perceive Islamism as an obstacle to their equality

and a linkage to patriarchal values. They argue that secularism was

important for protecting civil rights.

Secular states with majority Muslim populations

- Albania

- Azerbaijan

- Bosnia-Herzegovina

- Burkina Faso

- Chad

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Guinea

- Guinea-Bissau

- Indonesia (except Aceh)

- Kazakhstan

- Kosovo

- Kyrgyzstan

- Mali

- Niger

- Northern Cyprus

- Senegal

- Sierra Leone

- Tajikistan

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- Uzbekistan

- West Bank

Secularist movements by state

Turkey

Secularism in Turkey was both dramatic and far reaching as it filled the vacuum of the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. With the country getting down Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

led a political and cultural revolution. "Official Turkish modernity

took shape basically through a negation of the Islamic Ottoman system

and the adoption of a west-oriented mode of modernization."

- The Caliphate was abolished.

- Religious lodges and Sufi orders were banned.

- A secular civil code based on Swiss civil code was adopted to replace the previous codes based on Islamic law (shari’a) outlawing all forms of polygamy, annulled religious marriages, granted equal rights to men and women, in matters of inheritance, marriage and divorce.

- The religious court system and institutions of religious education were abolished.

- The use of religion for political purposes was banned.

- A separate institution was created that dealt with the religious matters of the people.

- The alphabet was changed from Arabic to Latin.

- A portion of religious activity was moved to the Turkish language, including the Adhan (call to prayer) which lasted until 1950. This was done by the second president of the republic of Turkey.

Throughout the 20th century secularism was continuously challenged by Islamists. At the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century, political Islamists and Islamic democrats such as the Welfare Party and Justice and Development Party

(AKP) gained in influence, with the AKP in the 2002 elections acquiring

government and holding on to it ever since with increasingly

authoritarian methods.

Lebanon

Lebanon is a parliamentary democracy within the overall framework of Confessionalism, a form of consociationalism in which the highest offices are proportionately reserved for representatives from certain religious communities.

A growing number of Lebanese, however, have organized against the confessionalist system, advocating for an installation of laïcité in the national government. The most recent expression of this secularist advocacy was the Laïque Pride march held in Beirut on April 26, 2010, as a response to Hizb ut-Tahrir's growing appeal in Beirut and its call to re-establish the Islamic caliphate.

Tunisia

Under the leadership of Habib Bourguiba (1956–1987), Tunisia’s post independence government pursued a program of secularization.

Bourguiba modified laws regarding habous (religious endowments),

secularized education and unified the legal system so that all

Tunisians, regardless of religion, were subject to the state courts. He

restricted the influence of the religious University of Ez-Zitouna

and replaced it with a faculty of theology integrated into the

University of Tunis, banned the headscarf for women, made members of the

religious hierarchy state employees and ordered that the expenses for

the upkeep of mosques and the salaries of preachers to be regulated.

Moreover, his best known legal innovations was the ‘Code du

Statut Personel’ (CSP) the laws governs issues related to the family:

marriage, guardianship of children, inheritance and most importantly the

abolishing of polygamy and making divorce subject to judicial review.

Bourguiba clearly

wanted to undercut the religious establishment’s ability to prevent his

secularization program, and although he was careful to locate these

changes within the framework of a modernist reading of Islam and

presented them as the product of ijtihad (independent interpretation) and not a break with Islam, he became well known for his secularism. John Esposito

says that "For Bourguiba, Islam represented the past; the west was

Tunisia's only hope for a modern future, but he was mistaken, Islam is

modernization"

Following increasing economic problems, Islamist movements came

about in 1970 with the revival of religious teaching in Ez-Zitouna

University and the influence which came from Arab religious leaders like

Syrian and Egyptian Muslim Brotherhoods. There is also influence by Hizb ut-Tahrir, whose members issue a magazine in Tunis named Azeytouna.

In the aftermath, the struggle between Bourguiba and Islamists became

uncontrolled and in order to repress the opposition the Islamist

leaderships were exiled, arrested and interrogated.

Ennahda Movement, also known as Renaissance Party or simply Ennahda, is a moderate Islamist political party in Tunisia. On 1 March 2011, after the secularist dictatorship of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali collapsed in the wake of the 2011 Tunisian revolution,

Tunisia's interim government granted the group permission to form a

political party. Since then it has become the biggest and most

well-organized party in Tunisia, so far outdistancing its more secular

competitors. In the Tunisian Constituent Assembly election, 2011,

the first honest election in the country's history with a turn out of

51.1% of all eligible voters, the party won 37.04% of the popular vote

and 89 (41%) of the 217 assembly seats, far more than any other party.

Egypt

Secularism in Egypt

has had a very important role to play in both the history of Egypt and

that of the Middle East. Egypt’s first experience of secularism started

with the British Occupation (1882–1952), the atmosphere which allowed

propagation of western ideas. In this environment, pro-secularist

intellectuals like Ya'qub Sarruf, Faris Nimr, Nicola Haddad who sought

political asylum from Ottoman Rule were able to publish their work. This

debate had then become a burning issue with the work of Egyptian Shaykh

Ali abd al-Raziq (1888–1966), "The most momentous document in the crucial intellectual and religious debate of modern Islamic history"

By 1919 Egypt had its first political secular entity called the Hizb 'Almani (Secular Party) this name was later changed to the Wafd party.

It combined secular policies with a nationalist agenda and had the

majority support in the following years against both the rule of the

king and the British influence. The Wafd party supported the allies

during World War II

and then proceeded to win the 1952 parliamentary elections, following

these elections the prime minister was overthrown by the King leading to

riots. These riots precipitated a military coup after which all

political parties were banned including the Wafd and the Muslim Brotherhood.

The government of Gamel Abdel Nasser

was secularist-nationalist in nature which at the time gathers a great

deal of support both in Egypt and other Arab states. Key elements of Nasserism:

- Secularist-Nationalist dictatorship: No religious or other political movements allowed to impact government.

- Modernization, Industrialization and Nationalization; Socialist economy

- Concentration on Arab values, identity and nationalism rather than Muslim values, identity and nationalism .

Secular legacy of Nasser's dictatorship influenced dictatorial periods of Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak and secularists ruled Egypt until 2011 Egyptian revolution. Nevertheless, the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood has become one of the most influential movements in the Islamic world, particularly in the Arab world. For many years it was

described as "semi-legal" and was the only opposition group in Egypt able to field candidates during elections. In the Egyptian parliamentary election, 2011–2012, the political parties identified as "Islamist" (the Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice Party, Salafi Al-Nour Party and liberal Islamist Al-Wasat Party) won 75% of the total seats. Mohamed Morsi, an Islamist democrat of Muslim Brotherhood was the first democratically elected president of Egypt. Nowadays, most Egyptian proponents of secularism emphasize the link between secularism and ‘national unity’ between Coptic Christians and Muslims.

Syria

The process of secularization in Syria began under the French mandate

in the 1920s and went on continuously under different governments since

the independence. Syria has been governed by the Arab nationalist Ba'ath Party since 1963. The Ba'ath government combined Arab socialism

with secular ideology and an authoritarian political system. The

constitution guarantees religious freedom for every recognized religious

communities, including many Christian denominations. All schools are

government-run and non-sectarian, although there is mandatory religious

instruction, provided in Islam and/or Christianity. Political forms of Islam are not tolerated by the government. The Syrian legal system is primarily based on civil law,

and was heavily influenced by the period of French rule. It is also

drawn in part from Egyptian law of Abdel Nasser, quite from the Ottoman Millet system and very little from Sharia.

Syria has separate secular and religious courts. Civil and criminal

cases are heard in secular courts, while the Sharia courts handle

personal, family, and religious matters in cases between Muslims or

between Muslims and non-Muslims. Non-Muslim communities have their own religious courts using their own religious law.

Iran

Following the military coup of 21 February 1921, Reza Khan had

established himself as the dominant political personality in the

country. Fearing that their influence might be diminished, the clergy of

Iran proposed their support and persuaded him to assume the role of the

Shah.

1925–1941: Reza Shah

began to make some dramatic changes to Iranian society with the

specific intention of westernization and removing religion from public

sphere. He changed religious schools to secular schools, built Iran’s

first secular university and banned the hijab in public. Nevertheless,

the regime became totally undemocratic and authoritarian with the

removal of Majles power (the first parliament in 1906) and the clampdown

on free speech.

1951–1953: During the early 1950s, Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh

was again forming a secular government with a socialist agenda with the

specific aim of reducing the power held by the clergy. However his plan

to nationalize the colonial oil interests held by the Anglo-Iranian Oil

Company, (later British Petroleum), attracted the ire of the United

Kingdom. In response, the United Kingdom with the help of the CIA, supported a coup which removed Mossadeq from power and reinstated Mohammad Reza Shah.

1962–1963: Using the mandate of westernization, Mohammad Reza Shah introduced White Revolution, aiming to transform Iran into a Westernized secular capitalist country.

1963–1973: Opposition rallied united behind Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and by the end of the 1970s the Shah was overthrown in an Islamic Revolution (1979).

Pakistan

Early in the history of the state of Pakistan (12 March 1949), a parliamentary resolution (the Objectives Resolution) was adopted, just a year after the death of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, in accordance with the vision of other founding fathers of Pakistan (Muhammad Iqbal, Liaquat Ali Khan). proclaiming:

Sovereignty belongs to Allah alone but He has delegated it to the State of Pakistan through its people for being exercised within the limits prescribed by Him as a sacred trust.

- The State shall exercise its powers and authority through the elected representatives of the people.

- The principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance and social justice, as enunciated by Islam, shall be fully observed.

- Muslims shall be enabled to order their lives in the individual and collective spheres in accordance with the teachings of Islam as set out in the Quran and Sunnah.

- Provision shall be made for the religious minorities to freely profess and practice their religions and develop their cultures.

According to Pakistani secularists, this resolution differed from the Muhammad Ali Jinnah's 11th August Speech

that he made in the Constitutive Assembly, but however, this resolution

was passed by the rest of members in the assembly after Muhammad Ali Jinnah's death in 1948. This resolution later became key source of inspiration for writers of Constitution of Pakistan and is included in constitution as preamble. However, Pakistan is an Islamic republic, with Islam as the state religion; it has aspects of secularism inherited from its colonial past. Islamists and Islamic democratic parties in Pakistan

are relatively less influential than democratic Islamists of other

Muslim democracies however they do enjoy considerable street power.

The Council of Islamic Ideology is a body that is supposed to advise the Parliament of Pakistan on bringing laws and legislation in alignment with the principles of the Quran and Sunnah, though it has no enforcement powers. The Federal Shariat Court can strike down any law deemed un-Islamic, though its decisions can be overturned by the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

Opposition and critique

Secularism and religion

Islamists believe that Islam fuses religion and politics, with normative political values determined by the divine texts.

It is argued that this has historically been the case and the

secularist/modernist efforts at secularizing politics are little more

than jahiliyyah (ignorance), kafir (unbelief/infidelity), irtidad (apostasy) and atheism. "Those who participated in secular politics were raising the flag of revolt against Allah and his messenger."

Saudi scholars denounce secularism as strictly prohibited in

Islamic tradition. The Saudi Arabian Directorate of Ifta', Preaching and

Guidance, has issued a directive decreeing that whoever believes that

there is a guidance (huda) more perfect than that of the Prophet, or that someone else's rule is better than his is a kafir.

It lists a number of specific tenets which would be regarded as a

serious departure from the precepts of Islam, punishable according to

Islamic law. For example:

- The belief that human made laws and constitutions are superior to the Shari'a.

- The opinion that Islam is limited to one's relation with God, and has nothing to do with the daily affairs of life.

- To disapprove of the application of the hudud (legal punishments decreed by God) that they are incompatible in the modern age.

- And whoever allows what God has prohibited is a kafir.

In the view of Tariq al-Bishri,

"secularism and Islam cannot agree except by means of talfiq [combining

the doctrines of more than one school, i.e., falsification], or by each

turning away from its true meaning."

Secularism and authoritarianism

A number of scholars believe that secular governments in Muslim

countries have become more repressive and authoritarian to combat the

spread of Islamism,

but this increased repression may have made many Muslim societies more

opposed to secularism and increased the popularity of Islamism the

Middle East.

Authoritarianism has left in many countries the mosque as the only place to voice political opposition. Scholars like Vali Nasr argue that the secular elites in the Muslim world were imposed by colonial powers to maintain hegemony.

Secularism is also associated with military regimes, such as those in Turkey and Algeria. The Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) succeeded in December 1991 elections in Algeria and the Welfare Party succeeded in the Turkish 1995 elections. However, both of these parties were eliminated through military coups in order to protect secularism.

While Welfare Party government in Turkey was forced to resign from the

office by Turkish military in February 1997 with a military intervention

which is called as "post modern coup", FIS in Algeria lived an austere military coup which carried the country in to a civil war in 1992. Military forces in those countries could use their power in undemocratic ways in order to ‘protect secularism’.

In some countries, the fear of Islamist takeover via democratic processes has led to authoritarian measures against Islamist political parties.

"The Syrian regime was able to capitalize on the fear of Islamist coming

to power to justify the massive clampdown on the Syrian Muslim

Brotherhood." When American diplomats asked Hosni Mubarak

to give more rights to the press and stop arresting the intellectuals,

Mubarak rejected it and said, "If I do what you ask, the fundamentalists

will take over the government in Egypt. Do you want that?" Or when

President Bill Clinton asked Yasser Arafat to establish democracy in Palestine in 2001, Yasser Arafat also replied similarly. "He said that in a democratic system Islamist Hamas will surely take control of the government in Palestine". Most secularist autocrats in the Middle East drew upon the risk of Islamism in order to justify their autocratic rule of government in the international arena.