Women in the Arab world live in situations that are rather unique, with special challenges not present in many other parts of the world. In particular these women have throughout history experienced discrimination and have been subject to restrictions of their freedoms and rights. Some of these practices are based on religious beliefs, but many of the limitations are cultural and emanate from tradition as well as religion.

These main constraints that create an obstacle towards women's rights

and liberties are reflected in laws dealing with criminal justice,

economy, education and healthcare.

Arab women before Islam

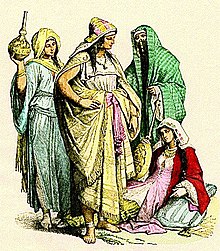

Costumes of Arab women, fourth to sixth century.

Many people / writers have discussed the status of women in pre-Islamic Arabia, and their findings have been mixed.

Under the customary tribal law existing in Arabia at the advent of

Islam, women as a general rule had virtually no legal status. They were

sold into marriage by their guardians for a price paid to the guardian,

the husband could terminate the union at will, and women had little or

no property or succession rights.

Some writers have argued that women before Islam were more liberated,

drawing most often on the first marriage of Muhammad and that of

Muhammad's parents, but also on other points such as worship of female

idols at Mecca.

Other writers, on the contrary, have agreed that women's status in

pre-Islamic Arabia was poor, citing practices of female infanticide,

unlimited polygyny, patrilineal marriage and others. Saudi historian Hatoon al-Fassi considers much earlier historical origins of Arab women's rights. Using evidence from the ancient Arabian kingdom of Nabataea, she finds that Arab women in Nabataea had independent legal personalities. She suggests that they lost many of their rights through ancient Greek and Roman law prior to the arrival of Islam and that these Greco-Roman constraints were retained under Islam. Valentine M. Moghadam analyzes the situation of women from a marxist

theoretical framework and argues that the position of women is mostly

influenced by the extent of urbanization, industrialization,

proletarization and political ploys of the state managers rather than

culture or intrinsic properties of Islam; Islam, Moghadam argues, is

neither more nor less patriarchal than other world religions especially

Christianity and Judaism.

In pre-Islamic Arabia,

women's status varied widely according to laws and cultural norms of

the tribes in which they lived. In the prosperous southern region of

the Arabian Peninsula, for example, the religious edicts of Christianity and Judaism held sway among the Sabians and Himyarites. In other places such as the city of Makkah (Mecca) -- where the prophet of Islam, Muhammad, was born—a tribal set of rights was in place. This was also true amongst the Bedouin

(desert dwellers), and this code varied from tribe to tribe. Thus there

was no single definition of the roles played, and rights held, by women

prior to the advent of Islam.

In some tribes, women were emancipated even in comparison with many of today's standards. There were instances where women held high positions of power and authority.

Pakistani lawyer Sundas Hoorain

has said that women in pre-Islamic Arabia had a much higher standing

than they got with Islam. She describes a free sex society in which

both men and women could have multiple partners or could contract a

monogamous relationship per their will. She thus concludes that the

Muslim idea of monogamy being a post-Islamic idea is flawed and biased

and that women had the right to contract such a marriage before Islam.

She also describes a society in which succession was matrilineal and

children were retained by the mother and lived with the mother's tribe,

whereas in Shariah law, young children stay with their mother until they

reach the age of puberty, and older children stay with their father.

Hoorain also cites problems with the idea of mass female infanticide and

simultaneous widespread polygamy (multiple women for one man), as she

sees it as an illogical paradox. She questions how it was possible for

men to have numerous women if so many females were being killed as

infants.

The custom of burying female infants alive, comments a noted Qur'anic commentator, Muhammad Asad,

seems to have been fairly widespread in pre-Islamic Arabia. The motives

were twofold: the fear that an increase in female offspring would

result in economic burden, as well as the fear of the humiliation

frequently caused by girls being captured by a hostile tribe and

subsequently preferring their captors to their parents and brothers.

It is generally accepted that Islam changed the structure of Arab

society and to a large degree unified the people, reforming and

standardizing gender roles throughout the region. According to Islamic studies professor William Montgomery Watt, Islam improved the status of women by "instituting rights of property ownership, inheritance, education and divorce."

The Hadiths in Bukhari suggest that Islam improved women's status, by the second Caliph Umar

saying "We never used to give significance to ladies in the days of the

Pre-Islamic period of ignorance, but when Islam came and Allah

mentioned their rights, we used to give them their rights but did not

allow them to interfere in our affairs", Book 77, Hadith 60, 5843, and

Vol. 7, Book 72, Hadith 734.

Arab women after Islam

A page from an Arabic manuscript from the 12th century, depicting a man playing the oud among women, (Hadith Bayad wa Riyad).

Islam was introduced in the Arabian peninsula in the seventh century,

and improved the status of women compared to earlier Arab cultures.

According to the Qur'anic decrees, both men and women have the same

duties and responsibilities in their worship of God.

As the Qur'an states: "I will not suffer to be lost the work of any of

you whether male or female. You proceed one from another".(Qur'an

3:195).

The Islamic studies professor William Montgomery Watt states:

It is true that Islam is still, in many ways, a man's religion. But I think I’ve found evidence in some of the early sources that seems to show that Muhammad made things better for women. It appears that in some parts of Arabia, notably in Mecca, a matrilineal system was in the process of being replaced by a patrilineal one at the time of Muhammad. Growing prosperity caused by a shifting of trade routes was accompanied by a growth in individualism. Men were amassing considerable personal wealth and wanted to be sure that this would be inherited by their own actual sons, and not simply by an extended family of their sisters’ sons. This led to a deterioration in the rights of women. At the time Islam began, the conditions of women were terrible - they had no right to own property, were supposed to be the property of the man, and if the man died everything went to his sons. Muhammad improved things quite a lot. By instituting rights of property ownership, inheritance, education and divorce, he gave women certain basic safeguards. Set in such historical context the Prophet can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women's rights.

Early reforms

During the early reforms under Islam in the 7th century, reforms in women's rights affected marriage, divorce and inheritance.

Lindsay Jones says that women were not accorded with such legal status

in other cultures, including the West, until centuries later. The Oxford Dictionary of Islam states that the general improvement of the status of Arab women included prohibition of female infanticide and recognizing women's full personhood. "The dowry,

previously regarded as a bride-price paid to the father, became a

nuptial gift retained by the wife as part of her personal property." Under Islamic law, marriage was no longer viewed as a "status" but rather as a "contract", in which the woman's consent was imperative. "Women were given inheritance rights in a patriarchal society that had previously restricted inheritance to male relatives." Annemarie Schimmel

states that "compared to the pre-Islamic position of women, Islamic

legislation meant an enormous progress; the woman has the right, at

least according to the letter of the law, to administer the wealth she

has brought into the family or has earned by her own work." William Montgomery Watt states that Muhammad, in the historical context of his time, can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women's rights and improved things considerably. Watt explains: "At the time Islam began, the conditions of women were terrible - they had no right to own property,

were supposed to be the property of the man, and if the man died

everything went to his sons." Muhammad, however, by "instituting rights

of property ownership, inheritance, education and divorce, gave women

certain basic safeguards." Haddad and state that "Muhammad granted women rights and privileges in the sphere of family life, marriage, education, and economic endeavors, rights that help improve women's status in society."

Education

Fatima al-Fihri founded the University of Al Karaouine in 859. In the Ayyubid dynasty in the 12th and 13th centuries, 160 mosques and madrasahs were established in Damascus, 26 of which were funded by women through the Waqf (charitable trust or trust law) system. Half of all the royal patrons for these institutions were also women. As a result, opportunities arose for female education in the medieval Islamic world. According to Sunni scholar Ibn Asakir in the 12th century, women could study, earn ijazahs (academic degrees), and qualify as scholars

and teachers. This was especially the case for learned and scholarly

families, who wanted to ensure the highest possible education for both

their sons and daughters. According to Aisha, the wife of the Muhammed, "How splendid were the women of Ansar; shame did not prevent them from becoming learned in the faith". According to a hadith attributed to Muhammad, he praised the women of Medina because of their desire for religious knowledge.

Sabat Islambouli (right), a Kurdish Jew and one of Syria's earliest female physicains; picture from 10 October 1885.

Employment

The labor force in the Arab Caliphate were employed from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds, while both men and women were involved in diverse occupations and economic activities. Women were employed in a wide range of commercial activities and diverse occupations. Women's economic position was strengthened by the Qur'an,

but local custom has weakened that position in its insistence that

women must work within private sector of the world: the home or at least

in some sphere related to home. Dr. Nadia YousaF, an Egyptian

sociologist now teaching in the United States, states in a recent

article on labor-force participation by women of Middle Eastern and

Latin American Countries that the "Middle East reports systematically

the lowest female activity rates on record" for labor. This certainly

gives the impression that Middle Eastern women have little or no

economical role, until one notes that the statistics are based on

non-agricultural labor outside the home.

In the 12th century, the most famous Islamic philosopher and qadi (judge) Ibn Rushd, known to the West as Averroes, claimed that women were equal to men in all respects and possessed equal capacities to shine in peace and in war, citing examples of female warriors among the Arabs, Greeks and Africans to support his case. In early Muslim history, examples of notable female Muslims who fought during the Muslim conquests and Fitna (civil wars) as soldiers or generals included Nusaybah Bint k’ab Al Maziniyyah, Aisha, Kahula, Wafeira, and Um Umarah.

Sabat M. Islambouli (1867-1941) was one of the first Syrian female physicians. She was a Kurdish Jew from Syria.

Contemporary Arab world

Queen Rania Al-Abdullah of Jordan is one of the Arab world's most high-profile educational campaigners.

Politics

There have been many highly respected female leaders in Muslim history, such as Shajar al-Durr (13th century) in Egypt, Asma bint Shihab (d. 1087) in Yemen and Razia Sultana (13th century) in Delhi.

In the modern era there have also been examples of female leadership in

Muslim countries, such as in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Turkey. However,

in Arabic-speaking countries no woman has ever been head of state,

although many Arabs remarked on the presence of women such as Jehan Al Sadat, the wife of Anwar El Sadat in Egypt, and Wassila Bourguiba, the wife of Habib Bourguiba in Tunisia, who have strongly influenced their husbands in their dealings with matters of state. Many Arab countries allow women to vote in national elections. The first female Member of Parliament in the Arab world was Rawya Ateya, who was elected in Egypt in 1957.

Some countries granted the female franchise in their constitutions

following independence, while some extended the franchise to women in

later constitutional amendments.

Arab women are under-represented in parliaments in Arab states,

although they are gaining more equal representation as Arab states

liberalise their political systems. In 2005, the International Parliamentary Union

said that 6.5 per cent of MPs in the Arab world were women, compared

with 3.5 per cent in 2000. In Tunisia, nearly 23 per cent of members of

parliament were women. However, the Arab country with the largest

parliament, Egypt, had only around four per cent female representation

in parliament. Algeria has the largest female representation in parliament with 32 per cent.

In the UAE,

in 2006 women stood for election for the first time in the country's

history. Although just one female candidate – from Abu Dhabi – was

directly elected, the government appointed a further eight women to the

40-seat federal legislature, giving women a 22.5 per cent share of the

seats, far higher than the world average of 17.0 per cent.

The role of women in politics in Arab societies is largely

determined by the will of these countries' leaderships to support female

representation and cultural attitudes towards women's involvement in

public life. Dr Rola Dashti,

a female candidate in Kuwait's 2006 parliamentary elections, claimed

that "the negative cultural and media attitude towards women in

politics" was one of the main reasons why no women were elected. She

also pointed to "ideological differences", with conservatives and

extremist Islamists opposing female participation in political life and

discouraging women from voting for a woman. She also cited malicious

gossip, attacks on the banners and publications of female candidates,

lack of training and corruption as barriers to electing female MPs. In contrast, one of UAE's female MPs, Najla al Awadhi,

claimed that "women's advancement is a national issue and we have a

leadership that understands that and wants them to have their rights."

Lebanon

recently appointed the first interior of state minister a female. This

move is consideret precendented in the Arab World, for she is the first

arab woman to hold this important position.

Politics of invisibility

Since the discussion of the representation of women in Arab societies

is being dissected, there should also be a discussion of Arab women

representation in western societies. The idea of "politics of

invisibility", was introduced by Amira Jarmakani, in the book Arab and Arab American Feminism: Gender, Violence, & Belonging

by Naber, Nadine Christine Alsultany, Evelyn Abdulhadi, and Rabab.

Jarmakani explains that Arab American Feminists are placed in a

paradoxical frame-work of being simultaneously invisible and

hypervisible.

Jarmakani called this, the "politics of invisibility", she argues that

one can actually use it in a creative way to gain positive attention to

important issues.

Jarmakani argues that because of the dominant representation of

Arab women given by the Bush administration many individuals in western

societies have an orientalist point of view, have Islamophobia and

believe that Arab feminism cannot exist.The reason for this is because

the Bush administration led the, "invasion of Afghanistan, as a project

of liberation meant to save Afghan women from the oppression of the

Taliban," this did not allow for the idea that there could be Arab

feminism.

Jarmakani explains that US based Feminist Majority Foundation has taken

on the role of savior instead of fighting with Arab feminists for

issues that they believed were important topics that need to be

addressed in their communities. This coupled with the invasion led to,

"reify stereotypical notions of Arab and Muslim womanhood as

monolithically oppressed. They depend on a set of U.S. cultural

mythologies about the Arab and Muslim worlds, which are often

promulgated through overdetermined signifiers, like the "veil" (the

English term collapsing a range of cultural and religious dress

expressing modesty, piety, or identity, or all three)".

She then concludes that because of the symbols that are used to

reinforce this they, "threaten to eclipse the creative work of Arab

American feminists. Because the mythologies are so pervasive, operating

subtly and insidiously on the register of "common sense," Arab American

feminists are often kept oriented toward correcting these common

misconceptions rather than focusing on our own agendas and concerns."

Because of these symbols, Arab women are placed in a paradox where,

"the marker (supposedly) of invisibility and cultural authenticity,

renders Arab and Muslim womanhood as simultaneously invisible and

hypervisible" because the veil is seen as a form of oppression and

becomes well known in the western societies as an oppressive form

therefore it brings hypervisibility to these women.

Because of this hypervisibility from symbols like the veil, it

makes it difficult to talk about the realities of Arab and Arab American

women's lives, "without invoking, and necessarily responding to, the

looming image and story that the mythology of the veil tells", she goes

on to state that the veil is not the only symbol, there are others such

as "honor killings" and "stoning". The argument that is being made is

that because of these symbols it is hard to talk about anything else

that is currently taking place in the lives of Arab and Arab American

women. These symbols make it difficult to focus on other important

issues, however Jarmakani states that because of this hypervisibility

Arab feminists can take advantage of it. She builds her argument off of

Joe Kadi from her essay, "Speaking about Silence" where Joe argues that

those who are silenced or being forced into being silent can break this

silence by speaking out. Jarmakani argues that unlike Joe who said one

should speak out, Jarmakani is stating to use the silence, meaning that

Arab women should use the hypervisibility that is being given by the

symbols of invisibility. Jarmakani ends with

"Simply advocating for a rejection of current stereotypical categories and narratives would inevitably lead to the establishment of equally limiting categories of representation, and spending energy to create a counterdiscourse will perhaps unwittingly reify the false binary that already frames much of public understanding. The work of Arab American feminists, then, must continue to encourage a fruitful fluidity that constantly forges new possibilities for understanding and contextualizing the complex realities of Arab and Arab American women's lives. In solidarity with social justice and liberation projects worldwide, we must mindfully utilize the tools of an oppositional consciousness in order to support the urgent work of carving and crafting new spaces for the expression of Arab American feminisms. Rather than simply resisting the politics of invisibility that have denied us a full presence, we must mobilize it, thereby reinventing and transforming that invisibility into a tool with which we will continue to illustrate the brilliant complexities of Arab and Arab American women's lives".

Women's right to vote in the Arab world

Samah Sabawi is a Palestinian dramatist, writer and journalist.

Women were granted the right to vote on a universal and equal basis in Lebanon in 1952, Syria (to vote) in 1949 (Restrictions or conditions lifted) in 1953, Egypt in 1956,

Tunisia in 1959, Mauritania in 1961, Algeria in 1962, Morocco in 1963, Libya, Sudan in 1964, Yemen in 1967 (full right) in 1970, Bahrain in 1973, Jordan in 1974, Iraq (full right) 1980, Kuwait in 1985 (later removed and re-granted in 2005), Oman in 1994, and Saudi Arabia in 2015.

Economic role

In some of the wealthier Arab countries such as UAE,

the number of women business owners is growing rapidly and adding to

the economic development of the country. Many of these women work with

family businesses and are encouraged to work and study outside of the

home.

Arab women are estimated to have $40 billion of personal wealth at

their disposal, with Qatari families being among the richest in the

world.

Education

Female

education rapidly increased after emancipation from foreign domination

around 1977. Before that, the illiteracy rate remained high among Arab

women. The gap between female and male enrollment varies across the Arab world. Countries like Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Lebanon, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates achieved almost equal enrollment rates between girls and boys. Female enrollment was as low as 10% in North of Yemen back in 1975. In Unesco's 2012 annual report, it predicted that Yemen won't achieve gender equality in education before 2025. In Qatar, the first school was built in 1956 after a fatwa that states that the Qur'an did not forbid female education.

Travel

Women

have varying degrees of difficulty moving freely in Arab countries. A

couple of nations prohibit women from ever traveling alone, while in

others women can travel freely but experience a greater risk of sexual

harassment or assault than they would in Western countries.

Women have the right to drive in all Arab countries with Saudi Arabia lifting the ban on June 24, 2018. In Jordan, travel restrictions on women were lifted in 2003.

"Jordanian law provides citizens the right to travel freely within the

country and abroad except in designated military areas. Unlike Jordan's

previous law (No. 2 of 1969), the current Provisional Passport Law (No. 5

of 2003) does not require women to seek permission from their male

guardians or husbands in order to renew or obtain a passport." In Yemen,

women must obtain approval from a husband or father to get an exit visa

to leave the country, and a woman may not take her children with her

without their father's permission, regardless of whether or not the

father has custody.

The ability of women to travel or move freely within Saudi Arabia is

severely restricted. However, in 2008 a new law went into effect

requiring men who marry non-Saudi women to allow their wife and any

children born to her to travel freely in and out of Saudi Arabia.

In Saudi Arabia, women must travel with their guardians permission and

they are not supposed to talk to strange random men, even if their lives

are in danger.

Traditional dress

Adherence to traditional dress varies across Arab societies. Saudi Arabia is more traditional, while countries like Egypt ,and Lebanon are less so. Women are required by law to wear abayas in only Saudi Arabia; this is enforced by the religious police. Some allege that this restricts their economic participation and other activities. In most countries, like Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Oman, Jordan, Syria and Egypt, the veil is not mandatory. The veil, hijab

in Arabic, means anything that hides.The hijab has been used to

describe the sexist oppression Arab women face, especially after the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks

on September 11, 2001. This use of the hijab "...capitalizes on the

image of exotic, oppressed women who must be saved from their indigenous

(hyper)patriarchy."

In doing so, the Arab woman is exoticized, marginalized, and

considered the other. To the United States military specifically, the

hijab symbolizes Arab women's sexist oppression. This idea has paved the

way for the U.S. military opposition against Arab communities, claiming

Arab women must be saved from the patriarchy and sexism they

experience. Global feminism has also taken part in this orientalism. The Feminist Majority Foundation

is an example of a global feminist group who have "...been advocating

on behalf of (but not with) Afghan women since at least the early

1990s."

They, like the United States military, have been fighting against the

hijab in an effort to save or free women of their oppression. Instead of

speaking with Arab women, global feminists speak for them, ultimately

silencing them in the process. Through this silencing, Arab women are

seen as incapable of defending themselves.

In Tunisia, the secular government has banned the use of the veil in its opposition to religious extremism. Former President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali

called the veil sectarian and foreign and has stressed the importance

of traditional Tunisian dress as a symbol of national identity. Islamic feminism counters both sorts of externally imposed dress codes.

Religious views differ on what is considered the proper hijab.

This explains the variation in Islamic attire according to geographic

location.

Conflation of Muslim and Arab identity

"Arab"

and "Muslim" are often used interchangeably. The conflation of these

two identities ignores the diverse religious beliefs of Arab people and

also overlooks Muslims who are not Arabs. It, "also erases the historic

and vast ethnic communities who are neither Arab nor Muslim but who live

amid and interact with a majority of Arabs or Muslims."

This generalization, "enables the construction of Arabs and Muslims as

backward, barbaric, misogynist, sexually savage, and sexually

repressive."

This type of stereotyping leads to the orientalizing of Arab women and

depicts them as fragile, sexually oppressed individuals who cannot stand

up for their beliefs.

Arab women and feminism

Egypt

is one of the leading countries with active feminist movements, and the

fight for women's right's is associated to social justice and secular

nationalism.

Egyptian feminism started out with informal networks of activism after

women were not granted the same rights as their male comrades in 1922.

The movements eventually resulted in women gaining the right to vote in

1956.

Although Lebanese Law does not give the lebanese woman her full rights, Lebanon

has a very large feminism movement. NGOs like Kafa and Abaad have

served this feminist obligation, and tried several times to pass adequat

laws that give the lebanese woman her rights. The most talked about

right is citizenship passing systems : a woman in Lebanon isn’t

authorised to pass her citizenship to her spouse nor her children. This

right is making a fuzz among lebanese, but has the people’s consent.

Feminists in Saudi Arabia can end up in jail or face a death penalty for their activism. Some

of their requests were granted such as not requiring a male guardian to

access government services. Women still need a male guardian's approval

to travel and marry.