From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In the

United States, a

religious freedom bill

is a bill that, according to its proponents, allows those with

religious objections to certain activities to act in accordance with

their beliefs without being punished by the government for doing so.

This typically concerns an employee who objects to abortion, euthanasia,

same-sex marriage,

or transgender identity and wishes to avoid situations where they will

be expected to put those objections aside. Proponents commonly refer to

such proposals as

religious liberty or

conscience protection.

Opponents of such bills frame them instead as "religious refusal bills", "bigot bills", or as a "license to discriminate"; pointing out that the legislation allows individuals and businesses to openly espouse prejudice, especially against

LGBT individuals.

History

In the 1960s, as a response to the desegregation of public schools, white Americans created many private schools (known as

"segregation academies"

or "freedom of choice schools") in the South. These schools gradually

became associated with evangelical Christianity. Those who supported the

schools, according to historian Joseph Crespino, said they were

defending the rights of religious minorities. As Corey Robin put it, "the heirs of slaveholders," in their imaginations, "became the descendants of persecuted Baptists, and

Jim Crow a heresy the First Amendment was meant to protect."

Controversy

Legal philosophy

The

trade-off at the heart of the controversy is whether antidiscrimination

laws must always be obeyed or whether other rights can be considered

more important, in effect granting the right to discriminate. Some

understand respect for individual human rights as foundational to

democracy and the rule of law,

but, at the same time, the First Amendment to the Constitution treats

freedom of religion as foundational and prevents the government from

making any law "prohibiting the free exercise" of religion.

The latter stance was taken in a U.S. presidential executive order

issued in May 2017 in which President Trump held that "the United States

Constitution enshrines and protects the fundamental right to religious

liberty as Americans' first freedom."

In July 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the creation of a

"religious liberty task force" under the Department of Justice to

implement the executive order's "guidance in the cases they [the

Department of Justice] bring and defend, the arguments they make in

court, the policies and regulations they adopt, and how we conduct our

operations.”

Richard Thompson Ford said that "overly broad conceptions of

civil rights protections have turned these important laws against

themselves," and that, while each protection may seem coherent on its

own, "in combination they constitute a recipe for unresolvable conflicts

of absolutes." A less abstract and more pragmatic approach, he argued,

might be to accord greater protection to minority religions and to

serious injuries. The famous case of Masterpiece Cakeshop fits

neither criterion, then, according to Ford, as the baker belonged to the

majority Christian religion and the customers weren't significantly

injured by having their wedding cake request denied.

Moral epistemology

Other

problems include how to demonstrate whether a belief is sincere,

whether it is factually informed and accurately corresponds to the

situation at hand, and whether it is indeed "religious" or "moral" in

its origin. Indiana University law professor Steve Sanders said that

"often there is no way to differentiate between genuine religious

convictions and beliefs that are made up out of convenience....an

employee who merely has a phobia toward transgender people might still

claim a 'religious' exemption, and the employer would have little choice

but to grant it."

Rhetoric

One

type of rhetorical frame depicts the religious freedom controversy as a

war of identities. The key is selecting identities to illustrate the

problem in a way that the illustration speaks for itself. For example,

one Catholic nun identified the question of "favoring the civil liberty

rights of transgender individuals over the conscience rights of public

service providers"; she sided with the public service providers. For a contrasting example, Rev. M Barclay, an openly transgender deacon in the United Methodist Church,

described the same question as "Christians using power and privilege to

target marginalized demographics like the LGBTQ community". These different angles are discussing the same question.

Legal challenges

After

the January 2018 creation of the Conscience and Religious Freedom

Division of the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Reuters

reported that "legal and medical ethics experts said that such

exemptions [to antidiscrimination law] have legal limits and would be

challenged in court."

In April 2018, a supporter of President Trump was asked to leave a

bar in New York City for wearing a "Make American Great Again" hat. The

customer's lawyer claimed in court that "The Make American Great Again

hat was part of his spiritual belief" (as it is illegal to discriminate

against people for their religious beliefs), while the bar's lawyer

claimed that "supporting Trump is not a religion." The judge dismissed

the case.

Support

From government

In May 2018, President Trump signed an executive order creating the White House Faith and Opportunity Initiative, an expansion of existing initiatives created by Bush and Obama.

Agencies and offices in the executive branch will have a liaison to the

newly expanded initiative if they do not already have a faith-based

program of their own.

According to the executive order, the Faith and Opportunity

Initiative will "notify the Attorney General, or his designee, of

concerns raised by faith-based and community organizations about any

failures of the executive branch to comply with protections of Federal

law for religious liberty" and seek to "reduce...burdens on the exercise

of religious convictions and legislative, regulatory, and other

barriers to the full and active engagement of faith-based and community

organizations in Government-funded or Government-conducted activities

and programs."

From activists

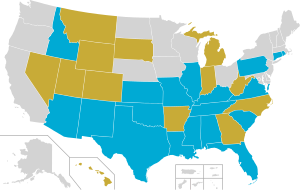

A coalition of conservative Christian organizations called

Project Blitz

supports, as of May 2018, over 70 bills across the United States, many

of which are religious liberty bills. One of the Project Blitz leaders

said in a conference call that the goal of having so many similar bills

was to force opponents to "divide their resources out in opposing this."

In 2017, the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation produced a 116-page

"playbook" with model legislation; the name "Project Blitz" is not used

in this report.

Situations in which discrimination may occur

Healthcare

Many healthcare types are potentially covered by

conscience-protection laws. In the U.S., as of 2013, these laws "are

increasingly being written in such a way that they would capture mental

health professionals".

On Jan. 18, 2018, the

Dept. of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced the creation of a new division within its existing Office for Civil Rights (OCR). The new division is called the

Conscience and Religious Freedom Division.

It was created to enforce federal laws related to "conscience and

religious freedom." That same day, Indiana University law professor

Steve Sanders criticized the new approach as having "the potential to

impede access to care, insult the dignity of patients, and allow

religious beliefs to override mainstream medical science."

Positions of medical organizations

Many

professional organizations for physicians and other healthcare

providers have ethics codes that forbid members from refusing care to

patients.

The ethics code of the American Medical Association allows

physicians to "refuse to participate in torture, interrogation or forced

treatment" but not to deny care based on a patient's "race, gender,

sexual orientation, gender identity, or any other criteria that would

constitute invidious discrimination."

The American Psychological Association believes that students

need to learn their future "ethical obligations regarding

non-discrimination" and requires broad-based diversity training "because

they may grow and change in their beliefs, preferences in populations

with whom they would like to work, geographic region, etc." While in

some cases it may be appropriate for a mental health provider to refer a

patient to another provider, this is not always practical, especially

in "schools and rural communities." The organization opposes

conscience-clause legislation, seeing it as an "intrusion of state

legislatures into the education and training of mental health

professionals".

The American Academy of Pediatrics supported repeal of

Tennessee's faith-healing law allowing parents to seek "treatment by

spiritual means through prayer alone" for their children. In 2008, the organization opposed conscience-clause legislation proposed at the federal level.

It released a statement that physicians practicing reproductive

medicine, as with any other kind of medicine, have "the obligation to

talk with patients about all of their options and, for services which

cannot or will not be provided, refer them to someone who can help them

without delay".

Scott Johnson, former president of the American Association for

Marriage and Family Therapy, said that conscience-based exemptions from

discrimination look "simply like prejudice" and that "the problem with

conscience is that it can let us do evil as well as good."

If a therapist violates AAMFT's Code of Ethics, the organization can

remove that person's membership in the professional organization even if

state law permits the therapist's behavior. The 2012 version of the

Code of Ethics "does not speak directly to matters of therapist values

or conscience."

Religious colleges

In

2006, California passed the Nondiscrimination in State Programs and

Activities Act (SB 1441) to withdraw state funding from private

universities that enforce a "moral code" regarding students' sexual

orientation or gender identity. Karen England, executive director of the

Capitol Resource Institute, described this as "an outright, blatant

assault on religious freedom.”

Between 2013 and 2015, the federal government granted over 30

exemptions to religious colleges who did not wish to comply with federal

antidiscrimination law applying to gender identity and sexual

orientation, according to a report by the Human Rights Coalition.

Basis for discrimination

Contraception and abortion

Following

Roe v. Wade,

the landmark abortion rights Supreme Court decision in 1973, "laws were

passed to ensure that hospitals or clinics that received federal funds

would be unable to force medical personnel who objected to abortion or

sterilization on the grounds of their 'religious beliefs or moral

convictions' to perform those procedures." At the end of President

George W. Bush's administration, "a new 'conscience clause' took effect,

cutting off federal funding for institutions that failed to accommodate

employees' religious or moral objections."

To those who believe abortion is murder, it may seem "a

particularly deadly form of authoritarianism" to "demand that physicians

kill their patients or help to arrange for the killing, even if they

believe doing so is wrong."

By 2005, in at least a dozen U.S. states, pharmacists had cited their

personal morality in their refusal to fill prescriptions for birth

control, including "emergency contraception" to prevent a fertilized egg

from implanting in the uterus.

Under the

Affordable Care Act, private health insurance plans must cover women's contraception without charging any

"out-of-pocket cost"

to the woman. The Trump administration moved to provide exemptions to

employers who claim moral or religious objections to providing

contraceptive coverage to their employees. In January 2019, a federal

judge blocked these rules from taking effect in 13 states and the

District of Columbia.

Euthanasia (assisted suicide)

Physicians can cause a patient's death "actively" (for example, by

administering a fatal drug) or "passively" (by withholding food, water,

or medical care that would prolong life). This option may be offered to

patients who are terminally ill and are severely disabled or in great

pain with no hope of recovery. If the patient is unable to communicate

or consent, sometimes family members may be asked to decide. This option

is called "

euthanasia," "

assisted suicide," or "mercy killing."

Physicians often consider themselves to be bound to the

Hippocratic Oath,

the original text of which was written between the fifth and third

centuries BCE and requires the physician to promise that he or she will

not "administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I

suggest such a course."

In the late twentieth century it became a subject of public debate in the United States in large part due to the work of

Jack Kevorkian, who claimed to have assisted 130 patient suicides. Surveys have shown that up to half of U.S. physicians have at some point received patient inquiries about assisted suicide.

The Catholic Church has long opposed euthanasia. In 1980, the

Vatican issued a Declaration on Euthanasia that explains: "The pleas of

gravely ill people who sometimes ask for death are not to be understood

as implying a true desire for euthanasia; in fact, it is almost always a

case of an anguished plea for help and love."

Same-sex marriage

Some clerks at city halls have refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. The most famous one is

Kim Davis,

county clerk for Rowan County, Kentucky, who claimed to be acting

"under God's authority" when she protested the nationwide legalization

of same-sex marriage in 2015 by refusing to issue marriage licenses to

couples of any gender. She served five days in jail for contempt of

court. Similarly, in 2015, a Tennessee judge protested the legalization

of same-sex marriage by his refusal to issue a divorce to an

opposite-sex couple. He argued that the Supreme Court's ruling revealed

that it believed the state of Tennessee "to be incompetent to define and

address such keystone/central institutions such as marriage, and,

thereby, at minimum, contested divorces" and said that he would wait for

further instruction from the Supreme Court.

Children of same-sex parents

In

2014, two women, Krista and Jami Contreras, met with a pediatrician in

Detroit shortly before the birth of their child. When the child was six

days old, they arrived for their appointment and were told that the

doctor had "prayed on it" and decided she could not provide care for the

child. A different doctor had been assigned to the family. The original

doctor later wrote to the couple: "After much prayer following your

prenatal, I felt that I would not be able to develop the personal

patient-doctor relationships that I normally do with my patients."

As of April 2018, five states (South Dakota, Michigan, Alabama,

Texas, Oklahoma) allow foster care agencies to refuse to place children

with same-sex guardians if the agency has "sincerely held religious

beliefs" against same-sex parenting.

Gender transition procedures

Gender

transition is an individualized process. Transgender people may seek

medical changes to their sexual characteristics according to their

physical and mental needs and preferences. A person may take hormones

(often administered by injection),

which they will generally then administer on a regular basis for the

rest of their life. They may also have various kinds of surgery

including breast augmentation or removal, genital reshaping, and removal

of reproductive organs. Transgender women may have facial feminization

surgery, an "Adam's apple reduction" to remove cartilage from the throat (tracheal shave), and electrolysis to remove unwanted facial and body hair.

Legal and institutional procedures may also be involved. The

transgender person may want to change their name and gender marker on

their identity documents, healthcare policy, and school or employment

registration. This may impact their marriage or divorce proceedings.

They may seek psychotherapy, either because they choose to do so

for their own reasons or because it is part of an established process

for gender transition. Some physicians will require a referral letter

from a psychotherapist. Transgender people "have routinely been asked to

obtain an endorsement letter from a psychologist attesting to the

stability of their gender identity as a prerequisite to access an

endocrinologist, surgeon, or legal institution (e.g., driver's license

bureau)".

A healthcare provider or administrative assistant who objects to

gender reassignment on principle might wish to decline to participate in

any or all of these procedures. One pitfall of such a conscience-based

refusal is that it is not always clear-cut when a procedure's primary

purpose is gender reassignment. After a person has taken initial major

steps to reassign their gender, ongoing procedures (like hormones,

electrolysis, or minor surgical corrections) may simply be considered as

"maintenance." In case of cancer prevention or treatment, reproductive

organs may need to be chemically disabled or removed, and if the patient

is coincidentally happy about the removal for their own personal

reasons, that does not necessarily mean the procedure is best thought of

as a component of gender transition. Cosmetic procedures may be

considered part of the universal human desire to look attractive and may

not obviously be gender-related. In psychotherapy, a person who happens

to be transgender may need to mention problems or circumstances that

are related to their gender identity or transition, events that may be

years in the past or future; this does not necessarily mean that the

psychotherapist is endorsing or helping them complete their gender

transition.

On the last day of the 2016 calendar year, just before the Obama

administration's new anti-discrimination policy under the Affordable

Care Act regarding gender identity and gender stereotypes was to take

effect, federal judge Reed O'Connor blocked it. O'Connor believed the anti-discrimination rule conflicted with the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. In April 2018, the Trump administration said it would roll back the anti-discrimination rule.

Transgender identity

Discriminating

against someone for their transgender identity is different than

refusing to participate in a specific action they are taking as part of

their gender transition. When the person is discriminated against for

their identity, the implication is that they are refused a product or

service that would normally be considered entirely unrelated to the

gender transition they have undergone or want to undergo.

Transgender people already have difficulty accessing healthcare.

Healthcare providers often have difficulty recognizing and separating

other dimensions of a transgender person's health apart from their

gender transition. The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey found that, just

within the past year, 15 percent of respondents said healthcare

providers had asked them "unnecessary or invasive questions about their

transgender status that were not related to the reason for their visit,"

while 3 percent were refused "care not related to gender transition

(such as physicals or care for the flu or diabetes)."

Roger Severino,

director of HHS Office of Civil Rights, in 2018 on the day that the

creation of the Conscience and Religious Freedom division was announced,

was asked by a journalist whether "someone who is transgender would be

denied health care" under the laws in question. He responded: "I think

denial is a very strong word...[healthcare] providers...simply want to

serve the people they serve according to their religious beliefs". Two days later, a

Boston Globe

editorial warned that the new HHS Conscience and Religious Freedom

division will "allow medical professionals and institutions who claim

religious objections to deny coverage to transgender people" which

"appears to open the way for a doctor or nurse to turn away a

transgender individual with a broken arm — for no other reason than by

their gender identity."

Marital status

In the 1990s, there were legal disputes regarding landlords who did not want to rent to unmarried couples.

Race

Some people claim that racial segregation is part of their religious beliefs. For example, in 2019, one of

Hoschton, Georgia's

city councilmen, Jim Cleveland, told a newspaper that "my Christian

beliefs are you don’t do interracial marriage. That’s the way I was

brought up and that’s the way I believe." He additionally told the

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

that seeing interracial black/white couples "makes my blood boil

because that’s just not the way a Christian is supposed to live."

Bob Jones University, a fundamentalist Christian school in South Carolina, prohibited interracial dating from the 1950s until 2000.

In 2015, law professor

David Bernstein

argued that, if ideological consistency is a guide, discrimination

against same-sex marriages would lead to discrimination against

"interracial or interreligious marriages."

In 2018, South Dakota state Rep. Michael Clark (R) commented on the Masterpiece Cakeshop

decision, saying that a hypothetical baker should be allowed to turn

away not only gay people but also people of color. "He should have the

opportunity to run his business the way he wants," Clark wrote on

Facebook. "If he wants to turn away people of color, then [that's] his

choice." He later deleted the comment and apologized, saying, "I would

never advocate discriminating against people based on their color or

race."

Side effects of discrimination

Apart

from the direct injury of any specific instance of discrimination,

there may be indirect effects of discriminatory law. Gay, lesbian, and

bisexual adults reported an increase in mental distress between 2014 and

2016 if they lived in U.S. states that permitted denial of services to

same-sex couples in 2015, whereas straight adults and people living in

other states did not report the same increase in mental distress. Similarly, an analysis by scientists at the University of Pittsburgh published in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry

found that, after Indiana passed a religious freedom law in 2015,

people in Indiana who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or who

question their sexual orientation self-reported worse physical and

mental health.

Federal law

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act is limited. It cannot be used

as a basis for discriminating against employees who identify as lesbian,

gay, bisexual, or transgender, according to a federal appeals court in

March 2018.

Massachusetts Rep. Joseph Kennedy III is sponsoring a proposed

amendment to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act that would prevent

people from claiming religious exemptions to nondiscrimination laws. The

amendment is called the Do No Harm Act (H.R. 3222).