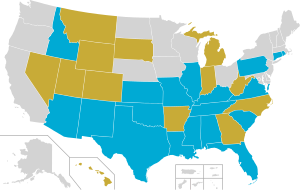

20 States had existing RFRA Laws prior to their 2015 legislative session

Sixteen states had RFRA legislation proposed during the 2015 legislative season. Only two, Indiana and Arkansas passed.

Some states have RFRA laws and LGBT anti-discrimination ordinances.

State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts are state laws based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), a federal law that was passed almost unanimously by the U.S. Congress in 1993 and signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

The laws mandate that religious liberty of individuals can only be

limited by the "least restrictive means of furthering a compelling

government interest".

Originally, the federal law was intended to apply to federal, state,

and local governments. In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court in City of Boerne v. Flores

held that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act only applies to the

federal government but not states and other local municipalities within

them. As a result, 21 states have passed their own RFRAs that apply to

their individual state and local governments.

Pre Hobby Lobby

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-141, 107 Stat. 1488 (November 16, 1993), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb through 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb-4 (also known as RFRA), is a 1993 United States federal law that "ensures that

interests in religious freedom are protected." The bill was introduced by Congressman Chuck Schumer (D-NY) on March 11, 1993. A companion bill was introduced in the Senate by Ted Kennedy (D-MA) the same day. A unanimous U.S. House and a nearly unanimous U.S. Senate—three senators voted against passage—passed the bill, and President Bill Clinton signed it into law.

The federal RFRA was held unconstitutional as applied to the states in the City of Boerne v. Flores

decision in 1997, which ruled that the RFRA is not a proper exercise of

Congress's enforcement power. However, it continues to be applied to

the federal government—for instance, in Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal—because

Congress has broad authority to carve out exemptions from federal laws

and regulations that it itself has authorized. In response to City of Boerne v. Flores

and other related RFRA issues, twenty-one individual states have passed

State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts that apply to state

governments and local municipalities.

State RFRA laws require the Sherbert Test, which was set forth by Sherbert v. Verner, and Wisconsin v. Yoder, mandating that strict scrutiny be used when determining whether the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution,

guaranteeing religious freedom, has been violated. In the federal

Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which usually serves as a model for

state RFRAs, Congress states in its findings that a religiously neutral

law can burden a religion just as much as one that was intended to

interfere with religion;

therefore the Act states that the "Government shall not substantially

burden a person's exercise of religion even if the burden results from a

rule of general applicability."

The federal RFRA provided an exception if two conditions are both

met. First, the burden must be necessary for the "furtherance of a

compelling government interest".

Under strict scrutiny, a government interest is compelling when it is

more than routine and does more than simply improve government

efficiency. A compelling interest relates directly with core

constitutional issues. The second condition is that the rule must be the least restrictive way in which to further the government interest.

Post Hobby Lobby

In 2014, the United States Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. recognizing a for-profit corporation's claim of religious belief.

Nineteen members of Congress who signed the original RFRA stated in a

submission to the Supreme Court that they "could not have anticipated,

and did not intend, such a broad and unprecedented expansion of RFRA".

The United States Government stated a similar position in a brief for

the case submitted before the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its

decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, writing that "Congress could

not have anticipated, and did not intend, such a broad and unprecedented

expansion of RFRA. ... The test Congress reinstated through RFRA ...

extended free-exercise rights only to individuals and to religious,

non-profit organizations. No Supreme Court precedent had extended

free-exercise rights to secular, for-profit corporations."

Following the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby decision, many states have proposed expanding state RFRA laws to include for-profit corporations, including in Arizona where SB 1062 passed by in Arizona but vetoed by Jan Brewer in 2014. Indiana SB 101

defines a "person" as "a partnership, a limited liability company, a

corporation, a company, a firm, a society, a joint-stock company, an

unincorporated association" or another entity driven by religious belief

that can sue and be sued, "regardless of whether the entity is

organized and operated for profit or nonprofit purposes". Indiana Democrats proposed an amendment that would not permit businesses to discriminate and the amendment was voted down.

An RFRA bill in Georgia has stalled, with constituents expressing

concern to Georgia lawmakers about the financial impacts of such a

bill. Stacey Evans proposed an amendment to change references of "persons" to "individuals", which would have eliminated closely held

for-profit corporations from the proposed law, but the amendment was

rejected because it would not give protections to closely held

corporations to practice religious freedoms granted by the Supreme Court

in the Hobby Lobby case.

Some commentators believe that the existence of a state-level RFRA bill in Washington could have affected the outcome of the Arlene's Flowers lawsuit, where a florist was prosecuted and convicted for refusal to provide flowers for a gay wedding.

Politifact

reports that "Conservatives in Indiana and elsewhere see the Religious

Freedom Restoration Act as a vehicle for fighting back against the

legalization of same-sex marriage."

Despite being of intense interest to religious groups, state RFRAs have

never been successfully used to defend discrimination against gays—and

have rarely been used at all.

The New York Times noted in March 2015 that state RFRAs became so

controversial is due to their timing, context and substance following

the Hobby Lobby decision.

Several law professors from Indiana stated that State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts like "Indiana SB 101" are in conflict with the U.S. Supreme Court's Free Exercise Clause

jurisprudence under that "neither the government nor the law may

accommodate religious belief by lifting burdens on religious actors if

doing so shifts those burdens to third parties. [...] The Supreme Court

has consistently held that the government may not accommodate religious

belief by lifting burdens on religious actors if that means shifting

meaningful burdens to third parties. This principle protects against the

possibility that the government could impose the beliefs of some

citizens on other citizens, thereby taking sides in religious disputes

among private parties. Avoiding that kind of official bias on questions

as charged as religious ones is a core norm of the First Amendment." The Supreme Court for example stated in Estate of Thornton v. Caldor, Inc.

(1985): "The First Amendment ... gives no one the right to insist that,

in pursuit of their own interests others must conform their conduct to

his own religious necessities.'" Relying on that statement they point

that the U.S. Constitution allows special exemptions for religious

actors, but only when they don't work to impose costs on others.

Insisting on "the constitutional importance of avoiding burdenshifting

to third parties when considering accommodations for religion" they

point out the case of United States v. Lee (1982). Here the court stated:

Congress and the courts have been sensitive to the needs flowing from the Free Exercise Clause, but every person cannot be shielded from all the burdens incident to exercising every aspect of the right to practice religious beliefs. When followers of a particular sect enter into commercial activity as a matter of choice, the limits they accept on their own conduct as a matter of conscience and faith are not to be superimposed on the statutory schemes which are binding on others in that activity. Granting an exemption from social security taxes to an employer operates to impose the employer's religious faith on the employees.

Effects of RFRAs on state court cases

Mandates courts use the following when considering religious liberty cases:

- Strict scrutiny

- Religious liberty can only be limited for a compelling government interest

- If religious liberty is to be limited, it must be done in the least restrictive manner possible

States with RFRAs

By legislature

Legislatures of 21 states have enacted versions of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act:

By state court decision

An additional 10 states have RFRA-like provisions that were provided by state court decisions rather than via legislation:

- Alaska

- Hawaii

- Ohio

- Maine

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Montana

- Washington

- Wisconsin

Reversals

Some states have had legislation withdrawn or vetoed. Arizona's bill SB 1062 was vetoed by Governor Jan Brewer. Bills 1161 and 1171 have been vetoed by a Colorado committee.

Additional details on specific state laws

Arkansas

In April 2015, the governor of Arkansas, Asa Hutchinson,

signed a religious freedom bill into law. The version of the bill he

signed was more narrow in scope than the original version, which would

have required state and local governments to demonstrate a compelling

governmental interest to be able to infringe on someone's religious

beliefs.

Georgia

In March 2016, the Georgia State Senate and the Georgia House of Representatives passed a religious freedom bill. On March 28, Georgia's governor, Nathan Deal, vetoed the bill after multiple Hollywood figures, as well as the Walt Disney Company threatened to pull future productions from the state if the bill became law. Many other companies had also been opposed to the bill, including the National Football League, Salesforce, the Coca-Cola Company, and Unilever.

Indiana

In March 2015, Mike Pence, the governor of Indiana, signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act

into law, which allowed business owners who objected to same-sex

couples on religious grounds to opt out of providing them services.

Mississippi

In April 2016, Phil Bryant, the governor of Mississippi,

signed into law a bill that protects people from government punishment

if they refuse to serve others on the basis of their own religious

objection to same-sex marriage, transgender people, or extramarital sex. The sponsors of "Project Blitz," a coalition of conservative Christian organizations supporting dozens of "religious liberty" bills at the state level across the United States, see Mississippi's law as model legislation.

Missouri

On March 9, 2016, the Missouri State Senate

passed a religious freedom bill. Senate Democrats tried to stop the

bill with a 39-hour filibuster, but Republicans responded by forcing a

vote using a rarely used procedural maneuver, which resulted in the bill

passing. In April, it was defeated 6-6 in a Missouri House of Representatives committee vote, with three Republicans joining three Democrats in voting against the bill.

South Dakota

On March 10, 2017, Dennis Daugaard, the governor of South Dakota,

signed into law SB 149, which allows taxpayer-funded adoption agencies

to deny services under circumstances that conflict with religious

beliefs.