Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the linguistic reconstruction of the ancient common ancestor of the Indo-European languages, the most widely spoken language family in the world.

Far more work has gone into reconstructing PIE than any other proto-language, and it is by far the best understood of all proto-languages of its age. The vast majority of linguistic work during the 19th century was devoted to the reconstruction of PIE or its daughter proto-languages (such as Proto-Germanic and Proto-Indo-Iranian), and most of the modern techniques of linguistic reconstruction (such as the comparative method) were developed as a result. These methods supply all current knowledge concerning PIE, since there is no written record of the language.

PIE is estimated to have been spoken as a single language from 4500 BC to 2500 BC during the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age, though estimates vary by more than a thousand years. According to the prevailing Kurgan hypothesis, the original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have been in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Eastern Europe. The linguistic reconstruction of PIE has also provided insight into the culture and religion of its speakers.

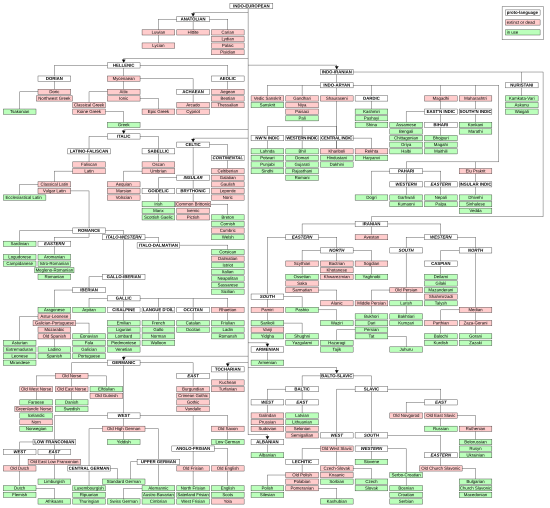

As speakers of Proto-Indo-European became isolated from each other through the Indo-European migrations, the regional dialects of Proto-Indo-European spoken by the various groups diverged from each other, as each dialect underwent different shifts in pronunciation (the Indo-European sound laws), morphology, and vocabulary. Thus these dialects slowly but eventually transformed into the known ancient Indo-European languages. From there, further linguistic divergence led to the evolution of their current descendants, the modern Indo-European languages. Today, the descendant languages, or daughter languages, of PIE with the most native speakers are Spanish, English, Portuguese, Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu), Bengali, Russian, Punjabi, German, Persian, French, Italian and Marathi. Hundreds of other living descendants of PIE include languages as diverse as Albanian (gjuha shqipe), Kurdish (کوردی), Nepali (खस भाषा), Tsakonian (τσακώνικα), Ukrainian (українська мова), and Welsh (Cymraeg).

PIE is believed to have had an elaborate system of morphology that included inflectional suffixes (analogous to English life, lives, life's, lives') as well as ablaut (vowel alterations, for example, as preserved in English sing, sang, sung) and accent. PIE nominals and pronouns had a complex system of declension, and verbs similarly had a complex system of conjugation. The PIE phonology, particles, numerals, and copula are also well-reconstructed.

An asterisk is used to mark reconstructed words, such as *wódr̥ 'water', *ḱwṓ 'dog', or *tréyes 'three (masculine)'; these forms are the reconstructed ancestors of the moden English words water, hound , and three.

Far more work has gone into reconstructing PIE than any other proto-language, and it is by far the best understood of all proto-languages of its age. The vast majority of linguistic work during the 19th century was devoted to the reconstruction of PIE or its daughter proto-languages (such as Proto-Germanic and Proto-Indo-Iranian), and most of the modern techniques of linguistic reconstruction (such as the comparative method) were developed as a result. These methods supply all current knowledge concerning PIE, since there is no written record of the language.

PIE is estimated to have been spoken as a single language from 4500 BC to 2500 BC during the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age, though estimates vary by more than a thousand years. According to the prevailing Kurgan hypothesis, the original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans may have been in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Eastern Europe. The linguistic reconstruction of PIE has also provided insight into the culture and religion of its speakers.

As speakers of Proto-Indo-European became isolated from each other through the Indo-European migrations, the regional dialects of Proto-Indo-European spoken by the various groups diverged from each other, as each dialect underwent different shifts in pronunciation (the Indo-European sound laws), morphology, and vocabulary. Thus these dialects slowly but eventually transformed into the known ancient Indo-European languages. From there, further linguistic divergence led to the evolution of their current descendants, the modern Indo-European languages. Today, the descendant languages, or daughter languages, of PIE with the most native speakers are Spanish, English, Portuguese, Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu), Bengali, Russian, Punjabi, German, Persian, French, Italian and Marathi. Hundreds of other living descendants of PIE include languages as diverse as Albanian (gjuha shqipe), Kurdish (کوردی), Nepali (खस भाषा), Tsakonian (τσακώνικα), Ukrainian (українська мова), and Welsh (Cymraeg).

PIE is believed to have had an elaborate system of morphology that included inflectional suffixes (analogous to English life, lives, life's, lives') as well as ablaut (vowel alterations, for example, as preserved in English sing, sang, sung) and accent. PIE nominals and pronouns had a complex system of declension, and verbs similarly had a complex system of conjugation. The PIE phonology, particles, numerals, and copula are also well-reconstructed.

An asterisk is used to mark reconstructed words, such as *wódr̥ 'water', *ḱwṓ 'dog', or *tréyes 'three (masculine)'; these forms are the reconstructed ancestors of the moden English words water, hound , and three.

Development of the hypothesis

No direct evidence of PIE exists – scholars have reconstructed PIE from its present-day descendants using the comparative method.

The comparative method follows the Neogrammarian rule: the Indo-European sound laws

apply without exception. The method compares languages and uses the

sound laws to find a common ancestor. For example, compare the pairs of

words in Italian and English: piede and foot, padre and father, pesce and fish.

Since there is a consistent correspondence of the initial consonants

that emerges far too frequently to be coincidental, one can assume that

these languages stem from a common parent language.

Many consider William Jones, an Anglo-Welsh philologist and puisne judge in Bengal, to have begun Indo-European studies in 1786, when he postulated the common ancestry of Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek.

However, he was not the first to make this observation. In the 1500s,

European visitors to the Indian subcontinent became aware of

similarities between Indo-Iranian languages and European languages, and as early as 1653 Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn had published a proposal for a proto-language ("Scythian") for the following language families: Germanic, Romance, Greek, Baltic, Slavic, Celtic, and Iranian. In a memoir sent to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1767 Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux,

a French Jesuit who spent all his life in India, had specifically

demonstrated the analogy between Sanskrit and European languages.

In the perspective of current academic consensus, Jones' work was less

accurate than his predecessors', as he erroneously included Egyptian, Japanese and Chinese in the Indo-European languages, while omitting Hindi.

In 1818 Rasmus Christian Rask

elaborated the set of correspondences to include other Indo-European

languages, such as Sanskrit and Greek, and the full range of consonants

involved. In 1816 Franz Bopp published On the System of Conjugation in Sanskrit in which he investigated a common origin of Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, and German. In 1833 he began publishing the Comparative Grammar of Sanskrit, Zend, Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Old Slavic, Gothic, and German.

In 1822 Jacob Grimm formulated what became known as Grimm's law as a general rule in his Deutsche Grammatik.

Grimm showed correlations between the Germanic and other Indo-European

languages and demonstrated that sound change systematically transforms

all words of a language. From the 1870s the Neogrammarians proposed that sound laws have no exceptions, as shown in Verner's law,

published in 1876, which resolved apparent exceptions to Grimm's law by

exploring the role that accent (stress) had played in language change.

August Schleicher's A Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European, Sanskrit, Greek and Latin Languages (1874–77) represented an early attempt to reconstruct the proto-Indo-European language.

By the early 1900s Indo-Europeanists had developed well-defined descriptions of PIE which scholars still accept today. Later, the discovery of the Anatolian and Tocharian languages added to the corpus of descendant languages. A new principle won wide acceptance in the laryngeal theory, which explained irregularities in the linguistic reconstruction

of Proto-Indo-European phonology as the effects of hypothetical sounds

which had disappeared from all documented languages, but which were

later observed in excavated cuneiform tablets in Anatolian.

Julius Pokorny's Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

("Indo-European Etymological Dictionary", 1959) gave a detailed, though

conservative, overview of the lexical knowledge then accumulated. Kuryłowicz's 1956 Apophonie gave a better understanding of Indo-European ablaut. From the 1960s, knowledge of Anatolian became robust enough to establish its relationship to PIE.

Historical and geographical setting

Scholars have proposed multiple hypotheses about when, where, and by whom PIE was spoken. The Kurgan hypothesis, first put forward in 1956 by Marija Gimbutas, has become the most popular of these. It proposes that the Yamna culture associated with the kurgans (burial mounds) on the Pontic–Caspian steppe north of the Black Sea were the original speakers of PIE.

According to the theory, PIE became widespread because its

speakers from the Kurgan culture could migrate into a vast area of

Europe and Asia thanks to technologies such as the domestication of the horse, herding, and the use of wheeled vehicles.

The people of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists,

who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BC had

expanded throughout the Pontic–Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.

Other theories include the Anatolian hypothesis, the Armenia hypothesis, the Paleolithic Continuity Theory, and the indigenous Aryans theory.

Due to early language contact, there are some lexical similarities between the Proto-Kartvelian and Proto-Indo-European languages.

An overview map summarises theories presented above.

Subfamilies (clades)

The following are listed by their theoretical glottochronological development:

Subfamily clades

| Description | Modern descendants | |

|---|---|---|

| Proto-Anatolian | All now extinct, the best attested being the Hittite language. | None |

| Proto-Tocharian | An extinct branch known from manuscripts dating from the 6th to the 8th century AD, which were found in north-west China. | None |

| Proto-Italic | This included many languages, but only descendants of Latin survive. | Portuguese and Galician, Occitan, Spanish, Catalan, French, Italian, Romanian, Aromanian, Rhaeto-Romance, Sardinian |

| Proto-Celtic | The ancestor of modern Celtic languages. Once spoken across Europe, but now mostly confined to its northwestern edge. | Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, Breton, Cornish, Manx |

| Proto-Germanic | The reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic languages. It developed into three branches: West Germanic, East Germanic (now extinct), and North Germanic. | English, German, Afrikaans, Dutch, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Frisian, Icelandic, Faroese |

| Proto-Balto-Slavic | Branched into the Baltic languages and the Slavic languages. | Baltic Latvian and Lithuanian; Slavic Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Serbo-Croatian, Bulgarian, Slovenian, Macedonian |

| Proto-Indo-Iranian | Branched into the Indo-Aryan, Iranian and Nuristani languages. | Indic Hindustani, Bengali, Sinhala, Punjabi, Dardic; Iranic Persian, Pashto, Balochi, Kurdish, Zaza, Ossetian, Luri, Talyshi, Tati, Gilaki, Mazandarani, Semnani, Old Azeri (extinct); Nuristani |

| Proto-Armenian |

|

Eastern Armenian, Western Armenian |

| Proto-Greek |

|

Modern Greek, Romeyka, Tsakonian |

| Proto-Albanian | Albanian is the only modern representative of a distinct branch of the Indo-European language family. | Albanian |

Common subgroups of Indo-European languages which are proposed include Italo-Celtic, Graeco-Aryan, Graeco-Armenian, Graeco-Phrygian, Daco-Thracian, and Thraco-Illyrian.

Marginally attested languages

The Lusitanian language is a marginally attested language found in the area of modern Portugal.

The Paleo-Balkan languages, which occur in or near the Balkan peninsula,

do not appear to be members of any of the subfamilies of PIE but are so

poorly attested that proper classification of them is not possible.

Albanian and Greek are the only surviving Indo-European languages in the

group.

Phonology

Proto-Indo-European phonology

has been reconstructed in some detail. Notable features of the most

widely accepted (but not uncontroversial) reconstruction include:

- three series of stop consonants reconstructed as voiceless, voiced, and breathy voiced;

- sonorant consonants that could be used syllabically;

- three so-called laryngeal consonants, whose exact pronunciation is not well-established but which are believed to have existed in part based on their visible effects on adjacent sounds;

- the fricative /s/; and

- a five-vowel system of which /e/ and /o/ were the most frequently occurring vowels.

The Proto-Indo-European accent

is reconstructed today as having had variable lexical stress, which

could appear on any syllable and whose position often varied among

different members of a paradigm (e.g. between singular and plural of a

verbal paradigm). Stressed syllables received a higher pitch; therefore

it is often said that PIE had a pitch accent.

The location of the stress is associated with ablaut variations,

especially between normal-grade vowels (/e/ and /o/) and zero-grade

(i.e. lack of a vowel), but not entirely predictable from it.

The accent is best preserved in Vedic Sanskrit and (in the case of nouns) Ancient Greek,

and indirectly attested in a number of phenomena in other IE languages.

To account for mismatches between the accent of Vedic Sanskrit and

Ancient Greek, as well as a few other phenomena, a few historical

linguists prefer to reconstruct PIE as a tone language where each morpheme

had an inherent tone; the sequence of tones in a word then evolved,

according to that hypothesis, into the placement of lexical stress in

different ways in different IE branches.

Morphology

Root

Proto-Indo-European roots were affix-lacking morphemes which carried the core lexical meaning of a word and were used to derive related words (e.g., "-friend-" in the English words "befriend", "friends", and "friend" by itself). Proto-Indo-European was a fusional language,

in which inflectional morphemes signalled the grammatical relationships

between words. This dependence on inflectional morphemes means that

roots in PIE, unlike those found in English, were rarely found by

themselves. A root plus a suffix formed a word stem, and a word stem plus a desinence (usually an ending) formed a word.

Ablaut

Many morphemes in Proto-Indo-European had short e as their inherent vowel; the Indo-European ablaut is the change of this short e to short o, long e (ē), long o (ō), or no vowel. This variation in vowels occurred both within inflectional morphology (e.g., different grammatical forms of a noun or verb may have different vowels) and derivational morphology (e.g., a verb and an associated abstract verbal noun may have different vowels).

Categories that PIE distinguished through ablaut were often also

identifiable by contrasting endings, but the loss of these endings in

some later Indo-European languages has led them to use ablaut alone to

identify grammatical categories, as in the Modern English words sing, sang, sung.

Noun

Proto-Indo-European nouns are declined for eight or nine cases:

- nominative: marks the subject of a verb, such as They in They ate. Words that follow a linking verb and rename the subject of that verb also use the nominative case. Thus, both They and linguists are in the nominative case in They are linguists. The nominative is the dictionary form of the noun.

- accusative: used for the direct object of a transitive verb.

- genitive: marks a noun as modifying another noun.

- dative: used to indicate the indirect object of a transitive verb, such as Jacob in Maria gave Jacob a drink.

- instrumental: marks the instrument or means by, or with which, the subject achieves or accomplishes an action. It may be either a physical object or an abstract concept.

- ablative: used to express motion away from something.

- locative: corresponds vaguely to the English prepositions in, on, at, and by.

- vocative: used for a word that identifies an addressee. A vocative expression is one of direct address where the identity of the party spoken to is set forth expressly within a sentence. For example, in the sentence, "I don't know, John", John is a vocative expression that indicates the party being addressed.

- allative: used as a type of locative case that expresses movement towards something. Only the Anatolian languages maintain this case, and it may not have existed in Proto-Indo-European at all.

There were three grammatical genders:

- masculine

- feminine

- neuter

Pronoun

Proto-Indo-European pronouns are difficult to reconstruct, owing to their variety in later languages. PIE had personal pronouns in the first and second grammatical person, but not the third person, where demonstrative pronouns were used instead. The personal pronouns had their own unique forms and endings, and some had two distinct stems; this is most obvious in the first person singular where the two stems are still preserved in English I and me. There were also two varieties for the accusative, genitive and dative cases, a stressed and an enclitic form.

|

|

First person | Second person | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | *h₁eǵ(oH/Hom) | *wei | *tuH | *yuH |

| Accusative | *h₁mé, *h₁me | *nsmé, *nōs | *twé | *usmé, *wōs |

| Genitive | *h₁méne, *h₁moi | *ns(er)o-, *nos | *tewe, *toi | *yus(er)o-, *wos |

| Dative | *h₁méǵʰio, *h₁moi | *nsmei, *ns | *tébʰio, *toi | *usmei |

| Instrumental | *h₁moí | *nsmoí | *toí | *usmoí |

| Ablative | *h₁med | *nsmed | *tued | *usmed |

| Locative | *h₁moí | *nsmi | *toí | *usmi |

Verb

Proto-Indo-European verbs, like the nouns, exhibited a system of ablaut. The most basic categorisation for the Indo-European verb was grammatical aspect. Verbs were classed as:

- stative: verbs that depict a state of being

- imperfective: verbs depicting ongoing, habitual or repeated action

- perfective: verbs depicting a completed action or actions viewed as an entire process.

Verbs have at least four grammatical moods:

- indicative: indicates that something is a statement of fact; in other words, to express what the speaker considers to be a known state of affairs, as in declarative sentences.

- imperative: forms commands or requests, including the giving of prohibition or permission, or any other kind of advice or exhortation.

- subjunctive: used to express various states of unreality such as wish, emotion, possibility, judgment, opinion, obligation, or action that has not yet occurred

- optative: indicates a wish or hope. It is similar to the cohortative mood and is closely related to the subjunctive mood.

Verbs had two grammatical voices:

- active: used in a clause whose subject expresses the main verb's agent.

- mediopassive: for the middle voice and the passive voice.

Verbs had three grammatical persons: (first, second and third).

Verbs had three grammatical numbers:

- singular

- dual: referring to precisely two of the entities (objects or persons) identified by the noun or pronoun.

- plural: a number other than singular or dual.

Verbs were also marked by a highly developed system of participles, one for each combination of tense and voice, and an assorted array of verbal nouns and adjectival formations.

The following table shows a possible reconstruction of the PIE

verb endings from Sihler, which largely represents the current consensus

among Indo-Europeanists.

|

|

Sihler (1995) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Athematic | Thematic | ||

| Singular | 1st | *-mi | *-oh₂ |

| 2nd | *-si | *-esi | |

| 3rd | *-ti | *-eti | |

| Dual | 1st | *-wos | *-owos |

| 2nd | *-th₁es | *-eth₁es | |

| 3rd | *-tes | *-etes | |

| Plural | 1st | *-mos | *-omos |

| 2nd | *-te | *-ete | |

| 3rd | *-nti | *-onti | |

Numbers

Proto-Indo-European numerals are generally reconstructed as follows.

|

|

Sihler |

|---|---|

| one | *(H)óynos/*(H)óywos/*(H)óyk(ʷ)os; *sḗm |

| two | *d(u)wóh₁ |

| three | *tréyes (full grade), *tri- (zero grade) |

| four | *kʷetwóres (o-grade), *kʷ(e)twr̥- (zero grade) |

| five | *pénkʷe |

| six | *s(w)éḱs; originally perhaps *wéḱs |

| seven | *septḿ̥ |

| eight | *oḱtṓ(w) or *h₃eḱtṓ(w) |

| nine | *h₁néwn̥ |

| ten | *déḱm̥(t) |

Rather than specifically 100, *ḱm̥tóm may originally have meant "a large number".

Particle

Proto-Indo-European particles could be used both as adverbs and postpositions, like *upo "under, below". The postpositions became prepositions in most daughter languages. Other reconstructible particles include negators (*ne, *mē), conjunctions (*kʷe "and", *wē "or" and others) and an interjection (*wai!, an expression of woe or agony).

Derivational morphology

Proto-Indo-European employed various means of deriving words from other words, or directly from verb roots.

Internal derivation

Internal

derivation was a process that derived new words through changes in

accent and ablaut alone. It was not as productive as external (affixing)

derivation, but is firmly established by the evidence of various later

languages.

Possessive adjectives

Possessive

or associated adjectives could be created from nouns through internal

derivation. Such words could be used directly as adjectives, or they

could be turned back into a noun without any change in morphology,

indicating someone or something characterised by the adjective. They

could also be used as the second element of a compound. If the first

element was a noun, this created an adjective that resembled a present

participle in meaning, e.g. "having much rice" or "cutting trees". When

turned back into nouns, such compounds were Bahuvrihis or semantically resembled agent nouns.

In thematic stems, creating a possessive adjective involved shifting the accent one syllable to the right, for example:

- *tómh₁-o-s "slice" (Greek tómos) → *tomh₁-ó-s "cutting" (i.e. "making slices"; Greek tomós) > *dr-u-tomh₁-ó-s "cutting trees" (Greek drutómos "woodcutter" with irregular accent).

- *wólh₁-o-s "wish" (Sanskrit vára-) → *wolh₁-ó-s "having wishes" (Sanskrit vará- "suitor").

In athematic stems, there was a change in the accent/ablaut class.

The known four classes followed an ordering, in which a derivation would

shift the class one to the right:

- acrostatic → proterokinetic → hysterokinetic → amphikinetic

The reason for this particular ordering of the classes in derivation is not known. Some examples:

- Acrostatic *krót-u-s ~ *krét-u-s "strength" (Sanskrit krátu-) > proterokinetic *krét-u-s ~ *kr̥t-éw-s "having strength, strong" (Greek kratús).

- Hysterokinetic *ph₂-tḗr ~ *ph₂-tr-és "father" (Greek patḗr) > amphikinetic *h₁su-péh₂-tōr ~ *h₁su-ph₂-tr-és "having a good father" (Greek eupátōr).

Vrddhi

A vrddhi

derivation, named after the Sanskrit grammatical term, signified "of,

belonging to, descended from". It was characterised by "upgrading" the

root grade, from zero to full (e) or from full to lengthened (ē).

When upgrading from zero to full grade, the vowel could sometimes be

inserted in the "wrong" place, creating a different stem from the

original full grade.

Examples:

- full grade *swéḱuro-s "father-in-law" (Vedic Sanskrit śváśura-) → lengthened grade *swēḱuró-s "relating to one's father-in-law" (Vedic śvāśura-, Old High German swāgur "brother-in-law").

- (*dyḗw-s ~) zero grade *diw-és "sky" > full grade *deyw-o-s "god, sky god" (Vedic devás, Latin deus, etc.). Note the difference in vowel placement, *dyew- in the full-grade stem of the original noun but *deyw- in the vrddhi derivative.

Nominalization

Adjectives

with accent on the thematic vowel could be turned into nouns by moving

the accent back onto the root. A zero grade root could remain so, or be

"upgraded" to full grade like in a vrddhi derivative. Some examples:

- PIE *ǵn̥h₁-tó-s "born" (Vedic jātá-) → *ǵénh₁-to- "thing that is born" (German Kind).

- Greek leukós "white" → leũkos "a kind of fish", literally "white one".

- Vedic kṛṣṇá- "dark" → kṛ́ṣṇa- "dark one", also "antelope".

This kind of derivation is likely related to the possessive adjectives, and can be seen as essentially the reverse of it.

Syntax

The syntax

of the older Indo-European languages has been studied in earnest since

at least the late nineteenth century, by such scholars as Hermann Hirt and Berthold Delbrück.

In the second half of the twentieth century, interest in the topic

increased and led to reconstructions of Proto-Indo-European syntax.

Since all the early attested IE languages were inflectional, PIE

is thought to have relied primarily on morphological markers, rather

than word order, to signal syntactic relationships within sentences. Still, a default (unmarked) word order is thought to have existed in PIE. This was reconstructed by Jacob Wackernagel as being subject–verb–object (SVO), based on evidence in Vedic Sanskrit, and the SVO hypothesis still has some adherents, but as of 2015 the "broad consensus" among PIE scholars is that PIE would have been a subject–object–verb (SOV) language.

The SOV default word order with other orders used to express emphasis (e.g., verb–subject–object to emphasise the verb) is attested in Old Indic, Old Iranian, Old Latin and Hittite, while traces of it can be found in the enclitic personal pronouns of the Tocharian languages.

A shift from OV to VO order is posited to have occurred in late PIE

since many of the descendant languages have this order: modern Greek, Romance and Albanian prefer SVO, Insular Celtic has VSO as the default order, and even the Anatolian languages show some signs of this word order shift. The inconsistent order preference in Baltic, Slavic and Germanic can be attributed to contact with outside OV languages.

In popular culture

The Ridley Scott film Prometheus features an android named "David" (played by Michael Fassbender)

who learns Proto-Indo-European to communicate with the "Engineer", an

extraterrestrial whose race may have created humans. David practices PIE

by reciting Schleicher's fable

and goes on to attempt communication with the Engineer through PIE.

Linguist Dr Anil Biltoo created the film's reconstructed dialogue and

had an onscreen role teaching David Schleicher's fable.