Yucatec Maya writing in the Dresden Codex, ca. 11–12th century, Chichen Itza

Indigenous languages of the Americas are spoken by indigenous peoples from Alaska, Nunavut, and Greenland to the southern tip of South America, encompassing the land masses that constitute the Americas. These indigenous languages consist of dozens of distinct language families, as well as many language isolates and unclassified languages.

Many proposals to group these into higher-level families have been made, such as Joseph Greenberg's Amerind hypothesis.

This scheme is rejected by nearly all specialists, due to the fact that

some of the languages differ too significantly to draw any connections

between them.

According to UNESCO, most of the indigenous American languages are critically endangered, and many are already extinct. The most widely spoken indigenous language is Southern Quechua, with about 6 to 7 million speakers, primarily in South America.

Background

Thousands of languages were spoken by various peoples in North and South America prior to their first contact with Europeans. These encounters occurred between the beginning of the 11th century (with the Nordic settlement of Greenland and failed efforts in Newfoundland and Labrador) and the end of the 15th century (the voyages of Christopher Columbus). Several indigenous cultures of the Americas had also developed their own writing systems, the best known being the Maya script. The indigenous languages of the Americas had widely varying demographics, from the Quechuan languages, Aymara, Guarani, and Nahuatl,

which had millions of active speakers, to many languages with only

several hundred speakers. After pre-Columbian times, several indigenous creole languages developed in the Americas, based on European, indigenous and African languages.

The European colonizers and their successor states had widely varying attitudes towards Native American languages. In Brazil, friars learned and promoted the Tupi language.

In many Latin American colonies, Spanish missionaries often learned

local languages and culture in order to preach to the natives in their

own tongue and relate the Christian message to their indigenous

religions. In the British American colonies, John Eliot of the Massachusetts Bay Colony translated the Bible into the Massachusett language, also called Wampanoag, or Natick (1661–1663; he published the first Bible printed in North America, the Eliot Indian Bible.

The Europeans also suppressed use of indigenous American

languages, establishing their own languages for official communications,

destroying texts in other languages, and insisting that indigenous

people learn European languages in schools. As a result, indigenous

American languages suffered from cultural suppression and loss of

speakers. By the 18th and 19th centuries, Spanish, English, Portuguese,

French, and Dutch, brought to the Americas by European settlers and

administrators, had become the official or national languages of modern

nation-states of the Americas.

Many indigenous languages have become critically endangered, but

others are vigorous and part of daily life for millions of people.

Several indigenous languages have been given official status in the

countries where they occur, such as Guaraní in Paraguay.

In other cases official status is limited to certain regions where the

languages are most spoken. Although sometimes enshrined in constitutions

as official, the languages may be used infrequently in de facto official use. Examples are Quechua in Peru and Aymara in Bolivia, where in practice, Spanish is dominant in all formal contexts.

In North America and the Arctic region, Greenland in 2009 adopted Kalaallisut as its sole official language. In the United States, the Navajo language is the most spoken Native American language, with more than 200,000 speakers in the Southwestern United States. The US Marine Corps recruited Navajo men, who were established as code talkers

during World War II, to transmit secret US military messages. Neither

the Germans nor Japanese ever deciphered the Navajo code, which was a

code using the Navajo language. Today, governments, universities, and

indigenous peoples are continuing to work for the preservation and

revitalization of indigenous American languages.

Origins

In American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (1997), Lyle Campbell lists several hypotheses for the historical origins of Amerindian languages.

- A single, one-language migration (not widely accepted)

- A few linguistically distinct migrations (favored by Edward Sapir)

- Multiple migrations

- Multilingual migrations (single migration with multiple languages)

- The influx of already diversified but related languages from the Old World

- Extinction of Old World linguistic relatives (while the New World ones survived)

- Migration along the Pacific coast instead of by the Bering Strait

Roger Blench

(2008) has advocated the theory of multiple migrations along the

Pacific coast of peoples from northeastern Asia, who already spoke

diverse languages. These proliferated in the New World.

Language families and unclassified languages

Notes:

- Extinct languages or families are indicated by: †.

- The number of family members is indicated in parentheses (for example, Arauan (9) means the Arauan family consists of nine languages).

- For convenience, the following list of language families is divided into three sections based on political boundaries of countries. These sections correspond roughly with the geographic regions (North, Central, and South America) but are not equivalent. This division cannot fully delineate indigenous culture areas.

North America

Pre-contact: distribution of North American language families, including northern Mexico

Bilingual stop sign in English and the Cherokee syllabary, Tahlequah, Oklahoma

There are approximately 296 spoken (or formerly spoken) indigenous

languages north of Mexico, 269 of which are grouped into 29 families

(the remaining 27 languages are either isolates or unclassified). The Na-Dené, Algic, and Uto-Aztecan

families are the largest in terms of number of languages. Uto-Aztecan

has the most speakers (1.95 million) if the languages in Mexico are

considered (mostly due to 1.5 million speakers of Nahuatl); Na-Dené comes in second with approximately 200,000 speakers (nearly 180,000 of these are speakers of Navajo), and Algic in third with about 180,000 speakers (mainly Cree and Ojibwe).

Na-Dené and Algic have the widest geographic distributions: Algic

currently spans from northeastern Canada across much of the continent

down to northeastern Mexico (due to later migrations of the Kickapoo) with two outliers in California (Yurok and Wiyot); Na-Dené spans from Alaska and western Canada through Washington, Oregon, and California to the U.S. Southwest

and northern Mexico (with one outlier in the Plains). Several families

consist of only 2 or 3 languages. Demonstrating genetic relationships

has proved difficult due to the great linguistic diversity present in

North America. Two large (super-) family proposals, Penutian and Hokan, look particularly promising. However, even after decades of research, a large number of families remain.

North America is notable for its linguistic diversity, especially

in California. This area has 18 language families comprising 74

languages (compared to four families in Europe: Indo-European, Uralic, Turkic, and Afroasiatic and one isolate: Basque).

Another area of considerable diversity appears to have been the Southeastern United States;

however, many of these languages became extinct from European contact

and as a result they are, for the most part, absent from the historical

record. This diversity has influenced the development of linguistic theories and practice in the US.

Due to the diversity of languages in North America, it is

difficult to make generalizations for the region. Most North American

languages have a relatively small number of vowels (i.e. three to five

vowels). Languages of the western half of North America often have

relatively large consonant inventories. The languages of the Pacific Northwest are notable for their complex phonotactics (for example, some languages have words that lack vowels entirely). The languages of the Plateau area have relatively rare pharyngeals and epiglottals (they are otherwise restricted to Afroasiatic languages and the languages of the Caucasus). Ejective consonants are also common in western North America, although they are rare elsewhere (except, again, for the Caucasus region, parts of Africa, and the Mayan family).

Head-marking

is found in many languages of North America (as well as in Central and

South America), but outside of the Americas it is rare. Many languages

throughout North America are polysynthetic (Eskimo–Aleut languages

are extreme examples), although this is not characteristic of all North

American languages (contrary to what was believed by 19th-century

linguists). Several families have unique traits, such as the inverse number marking of the Tanoan languages, the lexical affixes of the Wakashan, Salishan and Chimakuan languages, and the unusual verb structure of Na-Dené.

The classification below is a composite of Goddard (1996), Campbell (1997), and Mithun (1999).

- Adai †

- Algic (30)

- Alsea (2) †

- Atakapa †

- Beothuk †

- Caddoan (5)

- Cayuse †

- Chimakuan (2) †

- Chimariko †

- Chinookan (3) †

- Chitimacha †

- Chumashan (6) †

- Coahuilteco †

- Comecrudan (United States & Mexico) (3) †

- Coosan (2) †

- Cotoname †

- Eskimo–Aleut (7)

- Esselen †

- Haida

- Iroquoian (11)

- Kalapuyan (3) †

- Karankawa †

- Karuk

- Keresan (2)

- Kutenai

- Maiduan (4)

- Muskogean (9)

- Na-Dené (United States, Canada & Mexico) (39)

- Natchez †

- Palaihnihan (2)

- Plateau Penutian (4) (also known as Shahapwailutan)

- Pomoan (7)

- Salinan †

- Salishan (23)

- Shastan (4) †

- Siouan (19)

- Siuslaw †

- Solano †

- Takelma †

- Tanoan (7)

- Timucua †

- Tonkawa †

- Tsimshianic (2)

- Tunica †

- Utian (15) (also known as Miwok–Costanoan)

- Uto-Aztecan (33)

- Wakashan (7)

- Wappo †

- Washo

- Wintuan (4)

- Yana †

- Yokutsan (3)

- Yuchi

- Yuki †

- Yuman–Cochimí (11)

- Zuni

Central America and Mexico

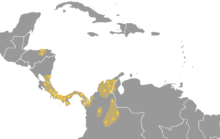

The indigenous languages of Mexico that have more than 100,000 speakers

The Mayan languages

In Central America the Mayan languages are among those used today. Mayan

languages are spoken by at least 6 million indigenous Maya, primarily

in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally

recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more.

The Mayan language family is one of the best documented and most

studied in the Americas. Modern Mayan languages descend from

Proto-Mayan, a language thought to have been spoken at least 4,000 years

ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method.

- Alagüilac (Guatemala) †

- Chibchan (Central America & South America)

- Coahuilteco †

- Comecrudan (Texas & Mexico) †

- Cotoname †

- Cuitlatec (Mexico: Guerrero) †

- Epi-Olmec (Mexico: language of undeciphered inscriptions) †

- Guaicurian

- Huave

- Jicaquean

- Lencan †

- Maratino (northeastern Mexico) †

- Mayan

- Misumalpan

- Mixe–Zoquean

- Naolan (Mexico: Tamaulipas) †

- Oto-Manguean

- Pericú †

- Purépecha

- Quinigua (northeast Mexico) †

- Seri

- Solano †

- Tequistlatecan

- Totonacan (2)

- Uto-Aztecan (United States & Mexico)

- Xincan (5) †

- Yuman (United States & Mexico)

South America and the Caribbean

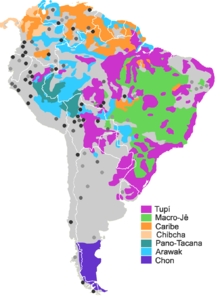

Some

of the greater families of South America: dark spots are language

isolates or quasi-isolate, grey spots unclassified languages or

languages with doubtful classification. (Note that Quechua, the family

with most speakers, is not displayed.)

Although both North and Central America

are very diverse areas, South America has a linguistic diversity

rivalled by only a few other places in the world with approximately 350

languages still spoken and an estimated 1,500 languages at first

European contact.

The situation of language documentation and classification into genetic

families is not as advanced as in North America (which is relatively

well studied in many areas). Kaufman (1994: 46) gives the following

appraisal:

Since the mid 1950s, the amount of published material on SA [South America] has been gradually growing, but even so, the number of researchers is far smaller than the growing number of linguistic communities whose speech should be documented. Given the current employment opportunities, it is not likely that the number of specialists in SA Indian languages will increase fast enough to document most of the surviving SA languages before they go out of use, as most of them unavoidably will. More work languishes in personal files than is published, but this is a standard problem.

It is fair to say that SA and New Guinea are linguistically the poorest documented parts of the world. However, in the early 1960s fairly systematic efforts were launched in Papua New Guinea, and that area – much smaller than SA, to be sure – is in general much better documented than any part of indigenous SA of comparable size.

As a result, many relationships between languages and language

families have not been determined and some of those relationships that

have been proposed are on somewhat shaky ground.

The list of language families, isolates, and unclassified

languages below is a rather conservative one based on Campbell (1997).

Many of the proposed (and often speculative) groupings of families can

be seen in Campbell (1997), Gordon (2005), Kaufman (1990, 1994), Key

(1979), Loukotka (1968), and in the Language stock proposals section below.

- Aguano †

- Aikaná (Brazil: Rondônia) (also known as Aikanã, Tubarão)

- Andaquí (also known as Andaqui, Andakí) †

- Andoque (Colombia, Peru) (also known as Andoke)

- Andoquero †

- Arauan (9)

- Arawakan (South America & Caribbean) (64) (also known as Maipurean)

- Arutani

- Aymaran (3)

- Baenan (Brazil: Bahia) (also known as Baenán, Baenã) †

- Barbacoan (8)

- Betoi (Colombia) (also known as Betoy, Jirara) †

- Bororoan

- Botocudoan (3) (also known as Aimoré)

- Cahuapanan (2) (also known as Jebero, Kawapánan)

- Camsá (Colombia) (also known as Sibundoy, Coche)

- Candoshi (also known as Maina, Kandoshi)

- Canichana (Bolivia) (also known as Canesi, Kanichana)

- Carabayo

- Cariban (29) (also known as Caribe, Carib)

- Catacaoan (also known as Katakáoan) †

- Cayubaba (Bolivia)

- Chapacuran (9) (also known as Chapacura-Wanham, Txapakúran)

- Charruan (also known as Charrúan) †

- Chibchan (Central America & South America) (22)

- Chimuan (3) †

- Chipaya–Uru (also known as Uru–Chipaya)

- Chiquitano

- Choco (10) (also known as Chocoan)

- Chon (2) (also known as Patagonian)

- Chono †

- Coeruna (Brazil) †

- Cofán (Colombia, Ecuador)

- Cueva †

- Culle (Peru) (also known as Culli, Linga, Kulyi) †

- Cunza (Chile, Bolivia, Argentina) (also known as Atacama, Atakama, Atacameño, Lipe, Kunsa) †

- Esmeraldeño (also known as Esmeralda, Takame) †

- Fulnió

- Gamela (Brazil: Maranhão) †

- Gorgotoqui (Bolivia) †

- Guaicuruan (7) (also known as Guaykuruan, Waikurúan)

- Guajiboan (4) (also known as Wahívoan)

- Guamo (Venezuela) (also known as Wamo) †

- Guató

- Harakmbut (2) (also known as Tuyoneri)

- Hibito–Cholon †

- Himarimã

- Hodï (Venezuela) (also known as Jotí, Hoti, Waruwaru)

- Huamoé (Brazil: Pernambuco) †

- Huaorani (Ecuador, Peru) (also known as Auca, Huaorani, Wao, Auka, Sabela, Waorani, Waodani)

- Huarpe (also known as Warpe) †

- Irantxe (Brazil: Mato Grosso)

- Itonama (Bolivia) (also known as Saramo, Machoto)

- Jabutian

- Je (13) (also known as Gê, Jêan, Gêan, Ye)

- Jeikó †

- Jirajaran (3) (also known as Hiraháran, Jirajarano, Jirajarana) †

- Jivaroan (2) (also known as Hívaro)

- Kaimbe

- Kaliana (also known as Caliana, Cariana, Sapé, Chirichano)

- Kamakanan †

- Kapixaná (Brazil: Rondônia) (also known as Kanoé, Kapishaná)

- Karajá

- Karirí (Brazil: Paraíba, Pernambuco, Ceará) †

- Katembrí †

- Katukinan (3) (also known as Catuquinan)

- Kawésqar (Chile) (Kaweskar, Alacaluf, Qawasqar, Halawalip, Aksaná, Hekaine)

- Kwaza (Koayá) (Brazil: Rondônia)

- Leco (Lapalapa, Leko)

- Lule (Argentina) (also known as Tonocoté)

- Maku (cf. other Maku)

- Malibú (also known as Malibu)

- Mapudungu (Chile, Argentina) (also known as Araucanian, Mapuche, Huilliche)

- Mascoyan (5) (also known as Maskóian, Mascoian)

- Matacoan (4) (also known as Mataguayan)

- Matanawí †

- Maxakalían (3) (also known as Mashakalían)

- Mocana (Colombia: Tubará) †

- Mosetenan (also known as Mosetén)

- Movima (Bolivia)

- Munichi (Peru) (also known as Muniche)

- Muran (4)

- Mutú (also known as Loco)

- Nadahup (5)

- Nambiquaran (5)

- Natú (Brazil: Pernambuco) †

- Nonuya (Peru, Colombia)

- Ofayé

- Old Catío–Nutabe (Colombia) †

- Omurano (Peru) (also known as Mayna, Mumurana, Numurana, Maina, Rimachu, Roamaina, Umurano) †

- Otí (Brazil: São Paulo) †

- Otomakoan (2) †

- Paez (also known as Nasa Yuwe)

- Palta †

- Pankararú (Brazil: Pernambuco) †

- Pano–Tacanan (33)

- Panzaleo (Ecuador) (also known as Latacunga, Quito, Pansaleo) †

- Patagon † (Peru)

- Peba–Yaguan (2) (also known as Yaguan, Yáwan, Peban)

- Pijao†

- Pre-Arawakan languages of the Greater Antilles (Guanahatabey, Macorix, Ciguayo) † (Cuba, Hispaniola)

- Puelche (Chile) (also known as Guenaken, Gennaken, Pampa, Pehuenche, Ranquelche) †

- Puinave (also known as Makú)

- Puquina (Bolivia) †

- Purian (2) †

- Quechuan (46)

- Rikbaktsá

- Saliban (2) (also known as Sálivan)

- Sechura (Atalan, Sec) †

- Tabancale † (Peru)

- Tairona (Colombia) †

- Tarairiú (Brazil: Rio Grande do Norte) †

- Taruma †

- Taushiro (Peru) (also known as Pinchi, Pinche)

- Tequiraca (Peru) (also known as Tekiraka, Avishiri) †

- Teushen † (Patagonia, Argentina)

- Ticuna (Colombia, Peru, Brazil) (also known as Magta, Tikuna, Tucuna, Tukna, Tukuna)

- Timotean (2) †

- Tiniguan (2) (also known as Tiníwan, Pamiguan) †

- Trumai (Brazil: Xingu, Mato Grosso)

- Tucanoan (15)

- Tupian (70, including Guaraní)

- Tuxá (Brazil: Bahia, Pernambuco) †

- Urarina (also known as Shimacu, Itukale, Shimaku)

- Vilela

- Wakona †

- Warao (Guyana, Surinam, Venezuela) (also known as Guarao)

- Witotoan (6) (also known as Huitotoan, Bora–Witótoan)

- Xokó (Brazil: Alagoas, Pernambuco) (also known as Shokó) †

- Xukurú (Brazil: Pernambuco, Paraíba) †

- Yaghan (Chile) (also known as Yámana)

- Yanomaman (4)

- Yaruro (also known as Jaruro)

- Yuracare (Bolivia)

- Yuri (Colombia, Brazil) (also known as Carabayo, Jurí) †

- Yurumanguí (Colombia) (also known as Yurimangui, Yurimangi) †

- Zamucoan (2)

- Zaparoan (5) (also known as Záparo)

Language stock proposals

Hypothetical language-family proposals of American languages are

often cited as uncontroversial in popular writing. However, many of

these proposals have not been fully demonstrated, or even demonstrated

at all. Some proposals are viewed by specialists in a favorable light,

believing that genetic relationships are very likely to be established

in the future (for example, the Penutian

stock). Other proposals are more controversial with many linguists

believing that some genetic relationships of a proposal may be

demonstrated but much of it undemonstrated (for example, Hokan–Siouan, which, incidentally, Edward Sapir called his "wastepaper basket stock"). Still other proposals are almost unanimously rejected by specialists (for example, Amerind). Below is a (partial) list of some such proposals:

- Algonquian–Wakashan (also known as Almosan)

- Almosan–Keresiouan (Almosan + Keresiouan)

- Amerind (all languages excepting Eskimo–Aleut & Na-Dené)

- Angonkian–Gulf (Algic + Beothuk + Gulf)

- (macro-)Arawakan

- Arutani–Sape (Ahuaque–Kalianan)

- Aztec–Tanoan (Uto-Aztecan + Tanoan)

- Chibchan–Paezan

- Chikitano–Boróroan

- Chimu–Chipaya

- Coahuiltecan (Coahuilteco + Cotoname + Comecrudan + Karankawa + Tonkawa)

- Cunza–Kapixanan

- Dené–Caucasian

- Dené–Yeniseian

- Esmerelda–Yaruroan

- Ge–Pano–Carib

- Guamo–Chapacuran

- Gulf (Muskogean + Natchez + Tunica)

- Macro-Kulyi–Cholónan

- Hokan (Karok + Chimariko + Shastan + Palaihnihan + Yana + Pomoan + Washo + Esselen + Yuman + Salinan + Chumashan + Seri + Tequistlatecan)

- Hokan–Siouan (Hokan + Keresiouan + Subtiaba–Tlappanec + Coahuiltecan + Yukian + Tunican + Natchez + Muskogean + Timucua)

- Je–Tupi–Carib

- Jivaroan–Cahuapanan

- Kalianan

- Kandoshi–Omurano–Taushiro

- (Macro-)Katembri–Taruma

- Kaweskar language area

- Keresiouan (Macro-Siouan + Keresan + Yuchi)

- Lule–Vilelan

- Macro-Andean

- Macro-Carib

- Macro-Chibchan

- Macro-Gê (also known as Macro-Jê)

- Macro-Jibaro

- Macro-Lekoan

- Macro-Mayan

- Macro-Otomákoan

- Macro-Paesan

- Macro-Panoan

- Macro-Puinavean

- Macro-Siouan (Siouan + Iroquoian + Caddoan)

- Macro-Tucanoan

- Macro-Tupí–Karibe

- Macro-Waikurúan

- Macro-Warpean (Muran + Matanawi + Huarpe)

- Mataco–Guaicuru

- Mosan (Salishan + Wakashan + Chimakuan)

- Mosetén–Chonan

- Mura–Matanawian

- Sapir's Na-Dené including Haida (Haida + Tlingit + Eyak + Athabaskan)

- Nostratic–Amerind

- Paezan (Andaqui + Paez + Panzaleo)

- Paezan–Barbacoan

- Penutian (many languages of California and sometimes languages in Mexico)

- California Penutian (Wintuan + Maiduan + Yokutsan + Utian)

- Oregon Penutian (Takelma + Coosan + Siuslaw + Alsean)

- Mexican Penutian (Mixe–Zoque + Huave)

- Puinave–Maku

- Quechumaran

- Saparo–Yawan (also known as Zaparo–Yaguan)

- Sechura–Catacao (also known as Sechura–Tallan)

- Takelman (Takelma + Kalapuyan)

- Tequiraca–Canichana

- Ticuna–Yuri (Yuri–Ticunan)

- Totozoque (Totonacan + Mixe–Zoque)

- Tunican (Tunica + Atakapa + Chitimacha)

- Yok–Utian

- Yuki–Wappo

Good discussions of past proposals can be found in Campbell (1997) and Campbell & Mithun (1979).

Amerindian linguist Lyle Campbell

also assigned different percentage values of probability and confidence

for various proposals of macro-families and language relationships,

depending on his views of the proposals' strengths. For example, the Germanic language family

would receive probability and confidence percentage values of +100% and

100%, respectively. However, if Turkish and Quechua were compared, the

probability value might be −95%, while the confidence value might be

95%. 0% probability or confidence would mean complete uncertainty.

| Language Family | Probability | Confidence |

|---|---|---|

| Algonkian–Gulf | −50% | 50% |

| Almosan (and beyond) | −75% | 50% |

| Atakapa–Chitimacha | −50% | 60% |

| Aztec–Tanoan | 0% | 50% |

| Coahuiltecan | −85% | 80% |

| Eskimo–Aleut, Chukotan |

−25% | 20% |

| Guaicurian–Hokan | 0% | 10% |

| Gulf | −25% | 40% |

| Hokan–Subtiaba | −90% | 75% |

| Jicaque–Hokan | −30% | 25% |

| Jicaque–Subtiaba | −60% | 80% |

| Jicaque–Tequistlatecan | +65% | 50% |

| Keresan and Uto-Aztecan | 0% | 60% |

| Keresan and Zuni | −40% | 40% |

| Macro-Mayan | +30% | 25% |

| Macro-Siouan | −20% | 75% |

| Maya–Chipaya | −80% | 95% |

| Maya–Chipaya–Yunga | −90% | 95% |

| Mexican Penutian | −40% | 60% |

| Misumalpan–Chibchan | +20% | 50% |

| Mosan | −60% | 65% |

| Na-Dene | 0% | 25% |

| Natchez–Muskogean | +40% | 20% |

| Nostratic–Amerind | −90% | 75% |

| Otomanguean–Huave | +25% | 25% |

| Purépecha–Quechua | −90% | 80% |

| Quechua as Hokan | −85% | 80% |

| Quechumaran | +50% | 50% |

| Sahaptian–Klamath–(Molala) | +75% | 50% |

| Sahaptian–Klamath–Tsimshian | +10% | 10% |

| Takelman | +80% | 60% |

| Tlapanec–Subtiaba as Otomanguean | +95% | 90% |

| Tlingit–Eyak–Athabaskan | +75% | 40% |

| Tunican | 0% | 20% |

| Wakashan and Chimakuan | 0% | 25% |

| Yukian–Gulf | −85% | 70% |

| Yukian–Siouan | −60% | 75% |

| Zuni–Penutian | −80% | 50% |

Unattested languages

Several

languages are only known by mention in historical documents or from

only a few names or words. It cannot be determined that these languages

actually existed or that the few recorded words are actually of known or

unknown languages. Some may simply be from a historian's errors. Others

are of known people with no linguistic record (sometimes due to lost

records). A short list is below.

- Ais

- Akokisa

- Aranama

- Ausaima

- Avoyel

- Bayagoula

- Bidai

- Cacán (Diaguita–Calchaquí)

- Calusa - Mayaimi - Tequesta

- Cusabo

- Eyeish

- Grigra

- Guale

- Houma

- Koroa

- Manek'enk (Haush) [perhaps Chon]

- Mayaca (possibly related to Ais)

- Mobila

- Okelousa

- Opelousa

- Pascagoula

- Pensacola - Chatot (Muscogean languages, possibly related to Choctaw)

- Quinipissa

- Taensa

- Tiou

- Yamacraw

- Yamasee

- Yazoo

Loukotka (1968) reports the names of hundreds of South American languages which do not have any linguistic documentation.