American Indian Movement

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Dennis Banks Clyde Bellecourt Vernon Bellecourt Russell Means |

| Founded | 1968 |

| Ideology | Anti-imperialism Anti-racism Ethnic nationalism Native American civil rights |

| Colors | Black Gold White Maroon |

| Website | |

| aimovement | |

The American Indian Movement (AIM) is a Native American grassroots movement in the United States, founded in July 1968 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. AIM was initially formed in urban areas to address systemic issues of poverty and police brutality against Native Americans.

A.I.M. soon widened it's focus from urban issues to include many

Indigenous tribal issues that Native American groups have faced due to settler colonialism of the Americas, such as treaty rights, high rates of unemployment, education, cultural continuity, and preservation of Indigenous cultures.

They simultaneously addressed incidents of police harassment and racism

against indigenous people, who were forced to move away from reservations and tribal culture by the Indian Termination Policies. AIM's paramount objective is to create "real economic independence for the Indians".

From November 1969 to June 1971, AIM participated in the occupation of the abandoned federal penitentiary known as Alcatraz, organized by seven Indian movements, including the Indian of All Tribes and Richard Oakes, a Mohawk activist.

In October 1972, AIM and other Indian groups gathered members from

across the United States for a protest in Washington, D.C. known as the Trail of Broken Treaties. According to public documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act

(FOIA), advanced coordination occurred between Washington, D.C.-based

Bureau of Indian Affairs (the BIA staff) and the authors of a

twenty-point proposal drafted with the help of the AIM for delivery to

the United States government officials focused on proposals intended to

enhance United States–Indian relations.

In the decades since AIM's founding, the group has led protests advocating indigenous

American interests, inspired cultural renewal, monitored police

activities and coordinated employment programs in cities and in rural

reservation communities across the United States. AIM has often

supported indigenous interests outside the United States as well. By

1993, AIM had split into two main factions. One faction is the AIM-Grand

Governing Council based in Minneapolis. The other faction is AIM-International Confederation of Autonomous Chapters, based in Denver Colorado.

Background

1950s

Proceeding the Indian Termination Policies directed by the Eisenhower administration,

uranium mining operations were established across Navajo tribal lands,

offering the only available employment to the Navajo people. Although

Navajo workers were initially enthusiastic about employment, it is

evident that the U.S. government had been aware of the harmful risks

associated with uranium mining since the 1930s and neglected to inform

the Navajo communities. In addition, the majority of Navajo workers did

not speak English, and therefore had no understanding of radiation, nor a

translation for the word in their language.

The open and now abandoned uranium mines continue to poison and pollute

the Navajo Communities today, and clean-up is in slow progress. The Navajo people feel that this was in violation of the Treaty of 1868 in which the Bureau of Indian Affairs was assigned to care for Navajo economic, educational, and health services.

1960s

On March 6, 1968, President Johnson signed Executive Order 11399, establishing the National Council on Indian Opportunity

(NCIO). President Johnson said "the time has come to focus our efforts

on the plight of the American Indian" and NCIO's formation would "launch

an undivided, Government-wide effort in this area". While knowing

little of the American Indian issues, Johnson tried to connect the

nation's trust responsibility to the tribes and nations to civil rights,

an area with which he was much more familiar.

A

member of the Warrior Society Mitakuye Oyasin wears an AIM jacket at

the raising of the John T. Williams Memorial Totem Pole, Seattle Center

In Congress, the Democratic chairman of the House Subcommittee on Indian Affairs, James Haley

from Florida, supported Indian rights; for example, he thought Indians

should participate more in "policy matters", but "the right of

self-determination is in the Congress as a representative of all the

people".

In the 1960s Haley met with president Kennedy and then-vice-president

Johnson, and pressed for Indian self-determination and control in

transactions over land. One struggle was over the long-term leasing of

American Indian land.

Non-Indian businesses and banks said they could not invest in leases of

25 years, even with generous options, as the time was too short for

land-based transactions. Relieving the long-term poverty on most

reservations through business partnerships by leasing land was seen as

infeasible. A return to the 19th century 99-year leases was seen as a

possible solution. But, an Interior Department memo said, "a 99-year

lease is in the nature of a conveyance of the land". These battles over

land had their beginnings in the 1870s when federal policy often related

to wholesale taking, not leases. In the 1950s, many Native Americans

believed that leases were too frequently a way for outsiders to control

Indian land.

Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson was a Tuscarora leader in New York in the 1950s. He struggled to resist the New York City planner Robert Moses'

plan to take tribal land in upstate New York for use in a state

hydropower project to supply New York City. The struggle ended in a

bitter compromise.

Initial movement

As had civil rights and antiwar

activists, AIM used the American press and media to present its message

to the United States public. It created events to attract the press. If

successful, news outlets would seek out AIM spokespersons for

interviews. Rather than relying on traditional lobbying efforts, AIM

took its message directly to the American public. Its leaders looked for

opportunities to gain publicity. Sound bites such as the "AIM Song" became associated with the movement.

Events

During

ceremonies on Thanksgiving Day 1970 to commemorate the 350th anniversary

of the Pilgrims' landing at Plymouth Rock, AIM seized the replica of

the Mayflower in Boston. In 1971, members occupied Mount Rushmore for a few days, as it was created in the Black Hills of South Dakota, long sacred to the Lakota. This area was within the Great Sioux Reservation as created by the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. After the discovery of gold, in 1874, the federal government took the land in 1877 and sold it for mining and settlement to European Americans.

Native American activists in Milwaukee

staged a takeover of an abandoned Coast Guard station along the Lake

Michigan. The takeover was inspired by the 1969 Alcatraz occupation.

Activists cited the Treaty of Fort Laramie

and demanded the abandoned federal property revert to the control of

the Native peoples of Milwaukee. AIM protestors retained possession of

the land, and the land became the site of the first Indian Community

School until 1980.

Also in 1971, AIM began to highlight and protest problems with the Bureau of Indian Affairs

(BIA), which administered programs and land trusts for Native

Americans. The group briefly occupied BIA headquarters in Washington,

D.C. A brief arrest, reversal of charges for "unlawful entry" and a

meeting with Louis Bruce, the Mohawk/Lakota BIA Commissioner, ended

AIM's first event in the capital. In 1972, activists marched across country on the "Trail of Broken Treaties" and took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), occupying it for several days and allegedly doing millions of dollars in damage.

AIM developed a 20-point list to summarize its issues with

federal treaties and promises, which they publicized during their

occupation in 1972. Twelve points addressed treaty responsibilities

which the protesters believed the U.S. government had failed to fulfill:

- Restore treaty-making (ended by Congress in 1871).

- Establish a treaty commission to make new treaties (with sovereign Native Nations).

- Provide opportunities for Indian leaders to address Congress directly.

- Review treaty commitments and violations.

- Have unratified treaties reviewed by the Senate.

- Ensure that all American Indians are governed by treaty relations.

- Provide relief to Native Nations as compensation for treaty rights violations.

- Recognize the right of Indians to interpret treaties.

- Create a Joint Congressional Committee to reconstruct relations with Indians.

- Restore 110 million acres (450,000 km2) of land taken away from Native Nations by the United States.

- Restore terminated rights of Native Nations.

- Repeal state jurisdiction on Native Nations (Public Law 280).

- Provide Federal protection for offenses against Indians.

- Abolish the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

- Create a new office of Federal Indian Relations.

- Remedy breakdown in the constitutionally prescribed relationships between the United States and Native Nations.

- Ensure immunity of Native Nations from state commerce regulation, taxes, and trade restrictions.

- Protect Indian religious freedom and cultural integrity.

- Establish national Indian voting with local options; free national Indian organizations from governmental controls.

- Reclaim and affirm health, housing, employment, economic development, and education for all Indian people.

In 1973 AIM was invited to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

to help gain justice from border counties' law enforcement and to

moderate political factions on the reservation. They became deeply

involved and led an armed occupation of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

in 1973. Other events during the 1970s were designed to achieve the

goal of gaining public attention. They ensured AIM would be noticed to

highlight what they saw as the erosion of Indian rights and sovereignty.

The Longest Walk and The Longest Walk 2

1978

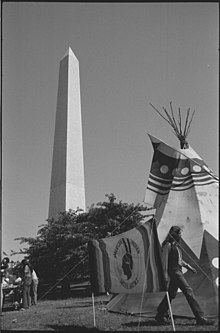

An American Indian Movement tipi on the grounds of the Washington Monument

The Longest Walk

(1978) was an AIM-led spiritual walk across the country to support

tribal sovereignty and bring attention to 11 pieces of anti-Indian

legislation; AIM believed that the proposed legislation would have

abrogated Indian Treaties, quantified and limited water rights. The

first walk began on February 11, 1978 with a ceremony on Alcatraz Island, where a Sacred Pipe

was loaded with tobacco. The Pipe was carried the entire distance. This

3,200-mile (5,100 km)-Walk's purpose was to educate people about the

government's continuing threat to Tribal Sovereignty; it rallied

thousands representing many Indian Nations throughout the United States

and Canada. Traditional spiritual leaders from many tribes participated,

leading traditional ceremonies. International spiritual leaders like Nichidatsu Fujii also took part in the Walk.

On July 15, 1978, The Longest Walk entered Washington, D.C. with

several thousand Indians and a number of non-Indian supporters. The

traditional elders led them to the Washington Monument,

where the Pipe carried across the country was smoked. Over the

following week, they held rallies at various sites to address issues:

the 11 pieces of legislation, American Indian political prisoners,

forced relocation at Big Mountain, the Navajo Nation, etc. Non-Indian supporters included the American boxer Muhammad Ali, US Senator Ted Kennedy and the actor Marlon Brando.

The Congress voted against a proposed bill to abrogate treaties with

Indian Nations. During the week after the activists arrived, Congress

passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which allowed them the use of peyote in worship. President Jimmy Carter refused to meet with representatives of The Longest Walk.

2008

Thirty years later, AIM led the Longest Walk 2,

which arrived in Washington in July 2008. This 8,200-mile

(13,200 km)-walk had started from the San Francisco Bay area. The

Longest Walk 2 had representatives from more than 100 American Indian

nations, and other indigenous participants, such as Maori.

It also had non-indigenous supporters. The walk highlighted the need

for protection of American Indian sacred sites, tribal sovereignty,

environmental protection and action to stop global warming.

Participants traveled on either the Northern Route (basically that of

1978) or the Southern Route. Participants crossed a total of 26 states

on the two different routes.

Northern Route

The

Northern Route was led by veterans of that action. The walkers used

Sacred staffs to represent their issues; the group supported the

protection of sacred sites of indigenous peoples, traditional tribal

sovereignty, issues related to native prisoners, and the protection of

children. They also commemorated the 30th anniversary of the original

Longest Walk.

Southern Route

Walkers

along the Southern Route picked up more than 8,000 bags of garbage on

their way to Washington. In Washington, the Southern Route delivered a

30-page manifesto, "The Manifesto of Change", and a list of demands,

including mitigation for climate change, a call for environmental

sustainability plans, protection of sacred sites, and renewal of

improvement to Native American sovereignty and health.

Connection to other people of color

AIM's leaders spoke out against injustices against their peoples, as had the African-American leaders of the Civil Rights Movement.

AIM leaders talked about high unemployment, slum housing, and racist

treatment, fought for treaty rights and the reclamation of tribal land,

and advocated on behalf of urban Indians.

With its provocative events and advocacy for Indian rights, AIM attracted scrutiny from the Department of Justice (DOJ). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) used paid informants to report on AIM's activities and its members.

In February 1973, AIM leaders Russell Means and Dennis Banks

worked with Oglala Lakota people and AIM activists to occupy the small

Indian community of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

They were protesting its corrupt government, federal issues, and the

lack of justice from border counties. The FBI dispatched agents and US Marshals

to cordon off the site. Later a higher-ranking DOJ representative took

control of the government's response. Through the resulting siege that

lasted for 71 days, twelve people were wounded, including an FBI agent

left paralyzed; in April a Cherokee and a Lakota activist died of

gunfire (at this point, the Oglala Lakota called an end to the

occupation). Afterward, 1200 American Indians were arrested. Wounded

Knee drew international attention to the plight of American Indians. AIM

leaders were tried in a Minnesota federal court. The court dismissed

their case on the basis of governmental prosecutorial misconduct.

History

AIM protests

AIM opposes national and collegiate sports teams using figures of indigenous people as mascots and team names, such as the Cleveland Indians, the Atlanta Braves, the Chicago Blackhawks, the Kansas City Chiefs and the Washington Redskins, and has organized protests at World Series and Super Bowl

games against these teams. Protesters held signs with slogans such as

"Indians are people not mascots". or "Being Indian is not a character

you can play".

Although sports teams had ignored such requests by individual tribes for years, AIM received attention in the mascot debate. NCAA schools such as Florida State University, University of Utah, University of Illinois and Central Michigan University

have negotiated with the tribes whose names or images they had used for

permission for continued use and to collaborate on portraying the

mascot in a way that is intended to honor Native Americans.

Goals and commitments

AIM

has been committed to improving conditions faced by native peoples. It

founded institutions to address needs, including the Heart of The Earth

School, Little Earth Housing, International Indian Treaty Council, AIM

StreetMedics, American Indian Opportunities and Industrialization Center (one of the largest Indian job training programs), KILI radio and Indian Legal Rights Centers.

In 1971, several members of AIM, including Dennis Banks and Russell Means, traveled to Mt. Rushmore. They converged at the mountain in order to protest the illegal seizure of the Sioux Nation's sacred Black Hills in 1877 by the United States federal government, in violation of its earlier 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The protest began to publicize the issues of the American Indian Movement.

In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government had

illegally taken the Black Hills. The government offered financial

compensation, but the Oglala Sioux have refused it, insisting on return

of the land to their people. The settlement money is earning interest.

Work at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

Border town cases

In 1972, Raymond Yellow Thunder, a 51-year-old Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge Reservation, was murdered in Gordon, Nebraska,

by two brothers, Leslie and Melvin Hare, younger white men. After their

trial and conviction, the Hares received the minimal sentence for manslaughter.

Members of AIM went to Gordon to protest the sentences, as it was seen

as part of a pattern of law enforcement in border counties that did not

provide justice to Native Americans. In the winter of 1973, Wesley Bad Heart Bull,

a Lakota, was stabbed to death at a bar in South Dakota by Darrell

Schmitz, a white male. The offender was jailed, but released on a $5000

bond and charged with second degree manslaughter.

In protest of the charges, a group of AIM members and leaders from Pine

Ridge Reservation and leaders went to the county seat of Custer, South Dakota,

to meet with the prosecutor. Police in riot gear allowed only four

people to enter the county courthouse. The talks were not successful,

and tempers rose over the police treatment; AIM activists caused $2

million in damages by attacking and burning the Custer Chamber of

Commerce building, the courthouse, and two patrol cars. Many of the AIM

demonstrators were arrested and charged; numerous people served

sentences, including the mother of Wesley Bad Heart Bull.

1973 Wounded Knee Incident

In addition to the problems of violence in the border towns, many traditional people at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation were unhappy with the government of Richard Wilson,

elected in 1972. When their effort to impeach him in February 1973

failed, they met to plan protests and action. Many people on the

reservation were unhappy about its longstanding poverty and failures of

the federal government to live up to its treaties with Indian nations.

The women elders encouraged the men to act. On February 27, 1973, about

300 Oglala Lakota and AIM activists went to the hamlet of Wounded Knee

for their protest. It developed into a 71-day siege, with the FBI

cordoning off the area by using US Marshals and later National Guard

units. The occupation was symbolically held at the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre.

The Oglala Lakota demanded a revival of treaty negotiations to begin to

correct relations with the federal government, the respect of their

sovereignty, and the removal of Wilson from office. The American Indians

occupied the Sacred Heart Church, the Gildersleeve Trading Post and

numerous homes of the village. Although periodic negotiations were held

between AIM spokesman and U.S. government negotiators, gunfire occurred

on both sides. A US Marshal, Lloyd Grimm, was wounded severely and

paralyzed. In April, a Cherokee from North Carolina and a Lakota AIM

member were shot and killed. The elders ended the occupation then.

For about a month afterward, journalists frequently interviewed

Indian spokesmen and the event received international coverage. The Department of Justice then excluded the press from access to Wounded Knee. The Academy Awards ceremony was held in Hollywood, where the actor Marlon Brando, a supporter of AIM, asked an Apache actress, Sacheen Littlefeather, to speak at the Oscars on his behalf. He had been nominated for his performance in The Godfather and won. Littlefeather arrived in full Apache regalia and read his statement that, owing to the "poor treatment of Native Americans

in the film industry," Brando would not accept the award. In

interviews, she also talked about the Wounded Knee occupation. The event

grabbed the attention of the US and the world media. The movement

considered the Awards ceremony publicity, together with Wounded Knee, as

a major event and public relations victory, as polls showed that

Americans were sympathetic to the Indian cause.

Pine Ridge Reservation violence

AIM

members continued to be active at Pine Ridge, although Wilson stayed in

office and was re-elected in 1974 in a contested election. Violent

deaths rose during a "reign of terror", and more than 300 political

opponents of his died violently during the next three years.

On June 26, 1975, two FBI agents Jack Coler and Ronald Williams were on

the Pine Ridge Reservation searching for someone who was wanted for

questioning relating to an assault and robbery of two ranch hands. The

FBI agents were driving in two unmarked cars and followed a red pick-up

truck matching the suspects description. The FBI agents were shot at by

the occupants of the vehicle and others. The agents managed to fire five

rounds before being killed, while at least 125 bullets were fired at

them. The agents were also shot at close range with physical evidence

suggesting that they had been executed. Later reinforcements arrived,

and Joe Stuntz, an AIM member who had taken part in the shootout was

fatally shot and was found wearing Coler's FBI jacket. Three AIM members

were indicted for the murders: Darryl Butler, Robert Robideau and Leonard Peltier,

who had escaped to Canada. An eyewitness testified that the three men

joined the shooting after it had started. In 1991, Peltier admitted

firing at Agents in an interview. Both Butler and Robideau were

acquitted at trial while Peltier was tried separately and

controversially convicted in 1976 and is serving two consecutive life

sentences. Amnesty International has referred to his case under its Unfair Trials category.

Informants true and false

In

late 1974, AIM leaders discovered that Douglas Durham, a prominent

member who was by then head of security, was an FBI informant. They

confronted him and expelled him from AIM at a press conference in March

1975. Durham's girlfriend, Jancita Eagle Deer, was later found dead

after being struck by a speeding car while many believed Durham was

guilty.

Durham was also scheduled to testify in front of the Church Committee,

but that hearing was suspended due to the illegal invasion of Pine Ridge

reservation and the subsequent shoot out.

With some members in fugitive status after the Pine Ridge

shootout, suspicions about FBI infiltration remained high. For various

reasons, Anna Mae Aquash,

the highest-ranking woman in AIM, was mistakenly suspected of being an

informant, even after she had voiced suspicions about Durham. Aquash had

also been threatened by FBI agent David Price.

According to testimony at trials in 2004 and 2010 of men convicted of

her murder, she was interrogated in the fall of 1975. In mid-December

she was taken from Denver, Colorado, to Rapid City, South Dakota, and

interrogated again, then taken to Rosebud Reservation and finally to a

far corner of Pine Ridge Reservation, where she was killed by a gunshot

wound to the back of the head. Her decomposing body was found February

1976. After the coroner failed to find the bullet hole in Aquash's head,

the FBI severed both of her hands and sent them to Washington, D.C.,

allegedly for identification purposes, then buried her as a Jane Doe. Aquash's body was later exhumed and given a second burial.

1980's support of Nicaraguan Miskito Indians

During the Sandinista/Indian conflict in Nicaragua of the mid-1980's, Russell Means sided with Miskito Indians

opposing the Sandinista government. The Miskito charged the government

with forcing relocations of as many as 8,500 Miskito. This position was

controversial among other left-wing, indigenous rights groups and

Central American solidarity organizations in the United States who

opposed Contra activities and supported the Sandinista movement.

The complex situation included Contra insurgents' recruiting among

Nicaraguan Indian groups, including some Miskitos. Means recognized the

difference between opposition to the Sandinista government by the Miskito, Sumo, and Rama on one hand, and the Reagan administration's support of the Contras, dedicated to the overthrow of the Sandinista regime.

AIM protests and contentions

Many

AIM chapters remain committed to confronting government and corporate

forces that they allege seek to marginalize Indigenous peoples. They have challenged the ideological foundations of US national holidays, such as Columbus Day and Thanksgiving. In 1970 AIM declared Thanksgiving a National Day of Mourning. This protest continues under the work of the United American Indians of New England, who protest continued theft of indigenous peoples' territories and natural resources.

AIM has helped educate people about the full history of the US, and

advocates for the inclusion of Indigenous American perspectives in U.S.

history. Its efforts are recognized and supported by many institutional

leaders in politics, education, arts, religion, and media.

Professor Ronald L. Grimes wrote that in 1984 "the Southwest

chapter of the American Indian Movement held a leadership conference

that passed a resolution labeling the expropriation of Indian ceremonies

(for instance, the use of sweat lodges, vision quests, and sacred

pipes) a "direct attack and theft". It also condemned certain named

individuals (such as Brooke Medicine Eagle, Wallace Black Elk, and Sun

Bear and his tribe) and criticized specific organizations such as Vision

Quest, Inc. The declaration threatened to take care of those abusing

sacred ceremonies.

2000s

In June

2003, United States and Canadian tribes joined together internationally

to pass the "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota

Spirituality." They felt they were being exploited by those marketing

the sales of replicated Native American spiritual objects and

impersonating sacred religious ceremonies as a tourist attraction. AIM

delegates are working on a policy to require tribal identification for

anyone claiming to represent Native Americans in any public forum or

venue.

In February 2004, AIM gained more media attention by marching from Washington, D.C. to Alcatraz Island. This was one of many occasions when Indian activists used the island as the location of an event since the Occupation of Alcatraz in 1969, led by the United Indians of All Tribes, a student group from San Francisco. The 2004 march was in support of Leonard Peltier,

whom many believed had not had a fair trial; he has become a symbol of

spiritual and political resistance for Native Americans.

In December 2008, a delegation of Lakota Sioux, including Talon Becenti, delivered to the U.S. State Department

a declaration of separation from the United States citing many broken

treaties by the U.S. government in the past, and the loss of vast

amounts of territory originally awarded in those treaties, the group

announced its intentions to form a separate nation within the U.S. known

as the Republic of Lakotah.

AIM timeline

- 1968 – Minneapolis AIM Patrol created to monitor police treatment of urban American Indians and their treatment in the justice system.

- 1969 – Indian Health Board of Minneapolis founded. This was the first American Indian, urban-based health care provider in the nation. The San Francisco-based United Indians of All Tribes and the Alcatraz-Red Power Movement occupied Alcatraz Island, a former federal prison site, for 19 months. They reclaimed federal land in the name of Native Nations. The first American Indian radio broadcasts—Radio Free Alcatraz—were heard in the Bay Area. Some AIM activists joined them.

- 1970 – Legal Rights Center created in Minneapolis to assist American Indians (as of 1994, over 19,000 clients have had legal representation thanks to AIM's work). AIM takeover of abandoned property at the naval air station near Minneapolis focuses attention on Indian education and leads to early grants for Indian education.

- 1971 – Citizen's arrest of John Old Crow. Takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs' headquarters in Washington, D.C. to publicize improper BIA policies. Twenty-four protesters arrested for trespassing and released. BIA Commissioner Louis Bruce shows his AIM membership card at the meeting held after the release of protesters. First National AIM Conference: 18 chapters of AIM convened to develop long-range strategy for the movement. Takeover of Winter Dam: AIM assists the Lac Court Oreilles (LCO) Ojibwe in Wisconsin in taking over a dam controlled by Northern States Power, which had flooded much of their reservation land. This action gained support by government officials and an eventual settlement with the LCO. The federal government returned more than 25,000 acres (100 km2) of land to the LCO tribe for their reservation, and the Power company provided significant monies and business opportunities to the tribe.

- 1972 – Red School House, the second survival school to open, offering culturally based education services to K-12 students in St. Paul, Minnesota. Hearth of the Earth Survival School (HOTESS), a K-12 school established to address the extremely high drop-out rate among American Indian students and lack of curricula that reflected American Indian culture. HOTESS serves as the first model of community-based, student-centered education with culturally correct curriculum operating under parental control. Trail of Broken Treaties, a pan-Indian march across country to Washington, D.C. to dramatize failures in federal policy. Protesters occupied the BIA national headquarters and did millions of dollars in damages, as well as irrevocable losses of Indian land deeds. The protesters presented a 20-point demand paper to the administration, many associated with treaty rights and renewed negotiations of treaties.

- 1973 – Legal action for school funds as in reaction to the Trail of Broken Treaties the government canceled education grants to three AIM-sponsored schools in St. Paul and Milwaukee. AIM files legal challenges, and the District Court orders the grants restored and government payment of costs and attorney fees. Wounded Knee: AIM was contacted by Oglala Lakota elders of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation for assistance in dealing with failures in justice in border towns, the authoritarian tribal president and financial corruption within the BIA and executive committee. Together with Oglala Lakota, armed activists occupied the town of Wounded Knee for 71-days against United States armed forces.

- 1973 – On February 27, 1973, a large public meeting of 600 Indians at Calico Hall organized by Pedro Bissonette of Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization (OSCRO) and addressed by AIM leaders Banks and Russell Means. Demands were made for investigations into vigilante incidents and for hearings on their treaties and permission given by the tribal elders to make a stand at Wounded Knee.

- 1974 – International Indian Treaty Council, an organization representing Indian peoples throughout the western hemisphere was recognized at the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland. Wounded Knee trials: eight months of federal trials of participants in Wounded Knee took place in Minneapolis. It was the longest Federal trial in the history of the United States. As many instances of government misconduct were revealed, the District judge Fred Nichol dismissed all charges due to government "misconduct" which "formed a pattern throughout the course of the trial" so that "the waters of justice have been polluted".

- 1975 – Federation of Survival Schools created to provide advocacy and networking skills to 16 survival schools throughout the United States and Canada. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) chose AIM to be the primary sponsor of the first American Indian-run housing project, Little Earth of United Tribes.

- 1977 – MIGIZI Communications founded in Minneapolis. The organization is dedicated to producing Indian news and information and educating students of all ages as tomorrow's technical work force. International Indian Treaty Council establishes non-government organization status at United Nations offices in Geneva; attends the International NGO conference and presents testimony to the United Nations. American Indian Language and Culture Legislation: AIM proposes legislative language which is passed in Minnesota, recognizing state responsibility for Indian education and culture. This legislation was recognized as a model throughout the country.

- 1978 – The first education programs for American Indian offenders: AIM establishes the first adult education program for American Indian offenders at Stillwater Prison in Minnesota. Programs later established at other state correctional facilities modeled after the Minnesota program. Circle of Life Survival School established on the White Earth Indian Reservation in Minnesota. The school receives funding for three years of operation from the Department of Education. Run for Survival: AIM youth organize and conduct 500-mile (800 km) run from Minneapolis to Lawrence, Kansas, to support The Longest Walk. The Longest Walk: Indian Nations walk across the United States from California to Washington, D.C. to protest proposed legislation calling for the abrogation of treaties with Indian nations. They set up and maintain a tipi near the White House. The proposed legislation is defeated.

- 1979 – Little Earth housing protected: an attempt by the HUD to foreclose on the Little Earth of United Tribes housing project is halted by legal action and the District Court issues an injunction against the HUD. The American Indian Opportunities Industrialiazation Center (AIOIC) creates job-training schools to alleviate the unemployment issues of Indian people. More than 17,000 Native Americans have been trained for jobs since AIM created the AIOIC in 1979. Anishinabe Akeeng Organization is created to regain stolen and tax-forfeited land on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota.

- 1984 – Federation of Native Controlled Survival Schools presents legal education seminars at colleges and law schools in Minnesota, Wisconsin, California, South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma for educators of Indian students. National conference held in San Jose, California, concurrent with the National Indian Education Association Convention.

- 1986 – Schools lewsuit: Heart of the Earth and Red School House successfully sue the Department of Education Indian Education Programs for ranking the schools' programs below funding recommendation levels. The suit proved discriminatory bias in the system of ranking by the Department staff.

- 1987 – AIM Patrol: Minneapolis AIM Patrol restarts to protect American Indian women in Minneapolis after serial killings committed against them.

- 1988 – Elaine Stately Indian Youth Services (ESIYS) developed to create alternatives for youth in Minneapolis as a direct diversion to gang-involvement of Indian youth. Fort Snelling AIM annual Pow Wow: AIM establishes an annual pow-wow to recognize its 20th anniversary at Fort Snelling in Minnesota. The event becomes the largest Labor Day weekend event in any Minnesota state park.

- 1989 – Spearfishing: AIM is requested to provide expertise in dealing with protesters at boat landings. American Indian spearfishing continues despite violence, arrests and threats from whites. Senator Daniel Inouye calls for a study on the effects of Indian spearfishing. The study shows only 6% of fish taken are by Indians. Sports fishing accounts for the rest.

- 1991 – Peacemaker Center: AIM houses its AIM Patrol and ESIYS in a center in the heart of the Indian community, based on Indian spirituality. Sundance returned to Minnesota: with the support of the Dakota communities, AIM revives the Sundance at Pipestone, Minnesota. Ojibwe nations have helped make the Minnesota Sundance possible. The Pipestone Sundance becomes an annual event. In 1991, some self-appointed leaders of the Oglala Lakota, Cheyenne and other nations declare independence from the United States. The group establishes a provisional government to develop a separate national government. Elected leaders and council members of the nations do not support this action. National Coalition on Racism in Sports and Media: AIM organizes this group to address the issue of using Indian figures and names as sports team mascots. AIM leads a walk in Minneapolis to the 1992 Super Bowl. In 1994, the Minneapolis Star Tribune agrees to stop using professional sports team names that refer to Indian people unless these have been approved by the tribes.

- 1992 – The Food Connection organizes summer youth jobs program with an organic garden and spiritual camp (Common Ground) at Tonkawood Farm in Orono, Minnesota.

- 1993 – Expansion of American Andian OIC Job Training Program: the Grand Metropolitan, Inc. of Great Britain, a parent of the Pillsbury Corporation, merges its job training program with that of AIOIC and pledges future monies and support in Minnesota. Little Earth: after AIM's 18-year struggle, the HUD secretary Henry Cisneros rules that Little Earth of United Tribes housing project shall retain the right to preference for American Indian residents when considering applicants for the project. Wounded Knee anniversary: at the 20th anniversary of the Wounded Knee Incident at Pine Ridge Reservation, the elected Oglala Sioux Tribe president John Yellow Bird Steele thanked AIM for its 1973 actions.

Due to continuing dissension, AIM splits. AIM Grand Governing Council

(AIMGGC) is based in Minneapolis and still led by founders while AIM-International Confederation of Autonomous Chapters is based in Denver, Colorado.

- 1996 – April 3–8, 1996: as a representative of the AIM Grand Governing Council and special representative of the International Indian Treaty Council, Vernon Bellecourt, along with William A. Means, president of IITC, attends the preparatory meeting for the Intercontinental Encounter for Humanity and Against Neo-Liberalism (IEHN), hosted by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), held in LaRealidad, Eastern Chiapas, Mexico between July 27 and August 3, 1996. The second meeting for the IEHN in 1997 is hosted by the EZLN and attended by delegates of the IITC and AIM.

- 1998 – February 12, 1998: AIM is charged with Security at the Ward Valley Occupation in Southern California. The occupation lasts for 113 days and results in a victory for the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) against the plan to use the area for the disposal of nuclear wastes. February 27, 1998: on the 25th anniversary of Wounded Knee, an Oglala Lakota Nation resolution establishes February 27 as a National Day of Liberation. July 16–19, 1998: the 25th annual Lac Courte Oreilles Honor the Earth Homecoming Celebration to honor the people who participated in the July 31, 1971 takeover of the Winter Dam and the beginning of the Honor the Earth observance. August 2–11, 1998: 30th Anniversary of the AIM Grand Governing Council and Sacred Pipestone Quarries in Pipestone, Minnesota. Conference commemorating AIM's 30th anniversary.

- 1999 – February 1999: three United States activists working with a group of UÕwa Indians in Colombia are kidnapped by rebels. Ingrid Washinawatok, 41 (Menominee), a humanitarian; Terence Freitas, 24, an environmental scientist from Santa Cruz, California; and LaheÕenaÕe Gay, 39 of Hawaii, are seized near the village of Royota, in Arauca province in northeastern Colombia on February 25 while preparing to leave after a two-week on-site visit. On March 5, their bullet-riddled bodies are discovered across the border in Venezuela.

- 2000 – July 2000: AIM 32nd anniversary Conference on the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Nation Reservation in northern Wisconsin. October 2000 – AIM founded commission to seek justice for Ingrid Washinawatok and companions.

- 2001 – March 2001: Reps of the AIM GGC attend the EZLN March for Peace, Justice and Dignity, Zocolo Plaza in Mexico City. July 2001 – 11th annual Youth & Elders International Cultural Gathering and Sundance in Pipestone, Minnesota. August 2001: five anti-wahoo demonstrators with AIM bring civil lawsuit for false arrest against the city of Cleveland, Ohio. November 2001 – The American Indian Forum on Racism in Sports and Media is held at Black Bear Crossing in St. Paul, Minnesota.

- 2002 – August 2002: 12th annual International Youth & Elders Cultural Gathering and Sundance in Pipestone, Minnesota.

- 2003 – May 2003: Quarterly Meeting of the AIM National Board of Directors Thunderbird House in Winnipeg, Manitoba. August 2003 – 13th Annual International Youth & Elders Cultural Gathering and Sundance, Pipestone, Minnesota.

- 2004 – August 2004: 14th annual International Youth & Elders Cultural Gathering and Sundance in Pipestone, Minnesota.

- 2005 – May 2005: 1st annual Clyde H. Bellecourt Endowment Scholarship Fund and Awards Banquet in Minneapolis. July 2005 – 15th annual International Youth & Elders Cultural Gathering and Sundance, Pipestone, Minnesota.

- 2006 – May 2006: 2nd annual Clyde H. Bellecourt Endowment Scholarship Fund and Awards Banquet in Minneapolis. July 2006 – 16th annual International Youth & Elders Cultural Gathering and Sundance, Pipestone, Minnesota.

Other Native American organizations

The

American Indian Movement founded several organizations since its

establishment in 1968. Its focus on cultural renewal and employment has

led to the creation of housing programs, the American Indian

Opportunities and Industrialization Center (for job training), and AIM

Street Medics, as well as a legal-aid center.

The American Opportunities and Industrialization Center, founded in

1979 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, has built a workforce of over 20,000

people from the entire Twin City area and tribal nations across the

country and is a nationally recognized leader in the workforce

development field. Following the AIM’s all-inclusive practice,

AIOC resources are available to all regardless of race, creed, age,

gender, or sexual orientation. The Tokama Institute, a division of the

AIOIC, is focused on helping American Indians acquire the foundational

skills and knowledge in order to obtain a successful career. Aside from

post-secondary institutions, AIM has helped develop and establish its

own K-12 schools including Heart of the Earth Survival School and the Little Red Schoolhouse both located in Minneapolis. Further, AIM has led to the establishment of Women of All Red Nations

(WARN). Established in 1974, WARN has put women at the forefront of the

organization and focused its energies in combating sexism, government

sterilization policies, and other injustices.

Other Native American organizations include NATIVE (Native American

Traditions, Ideals, Values Educational Society), LISN (League of

Indigenous Sovereign Nations), EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation), and the IPC (Indigenous Peoples Caucus).[43]

Although each group may have its own specific goals or focus, they are

all fighting for the same principles of respect and equality for Native

Americans. The Northwest Territories Indian Brotherhood, the Committee

of Original People's Entitlement were two organization that spearheaded

the native rights movement in northern Canada during the 1960s.

International Indian Treaty Council

AIM

established the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) in June

1974. It invited representatives from numerous indigenous nations, and

delegates from 98 international groups attended the meeting. The sacred

pipe serves as a symbol of the Nations "common bonds of spirituality,

ties to the land and respect for traditional cultures". The IITC

focuses on issues such as treaty and land rights, rights and protection

of indigenous children, protection of sacred sites, and religious

freedom.

The International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) uses networking,

technical assistance, and coalition building. In 1977, the IITC became a

Non-Governmental Organization with Consultative Status to the United

Nations Economic and Social Council. The organization concentrates on

involving Indigenous Peoples in U.N. forums. In addition, the IITC

strives to bring awareness about the issues concerning Indigenous

Peoples to non-Indigenous organizations.

United Nations adoption of indigenous peoples' rights

On

September 13, 2007, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the

"Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples". A total of 144 states

or countries voted in favor. Four voted against it while 11 abstained.

The four voting against it were the United States, Canada, Australia,

and New Zealand, whose representatives said they believed the

declaration "goes too far".

The Declaration announces rights of indigenous peoples, such as

rights to self-determination, traditional lands and territories,

traditional languages and customs, natural resources and sacred sites.

Ideological differences within AIM

In 1993, AIM split into two factions, each claiming to be the

authentic inheritor of the AIM tradition. The AIM-Grand Governing

Council is based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and associated with leadership by Clyde Bellecourt and his brother Vernon Bellecourt (who died in 2007). The GGC tends toward a more centralized, controlled political philosophy.

The AIM-International Confederation of Autonomous Chapters, based in Denver, Colorado, was founded by thirteen AIM chapters in 1993 at a meeting in Denver, Colorado. The group issued its Edgewood Declaration,

citing organizational grievances and complaining of authoritarian

leadership by the Bellecourts. Ideological differences were growing,

with the AIM-International Confederation of Autonomous Chapters taking a

spiritual, perhaps more mainstream, approach to activism. The

autonomous chapters group argues that AIM has always been organized as a

series of decentralized, autonomous chapters, with local leadership

accountable to local constituencies. The autonomous chapters reject the

assertions of central control by the Minneapolis group as contrary both

to indigenous political traditions and to the original philosophy of

AIM.

Accusations of murder

At a press conference in Denver, Colorado on 3 November 1999, Russell Means accused Vernon Bellecourt of having ordered the execution of Anna Mae Aquash

in 1975. The "highest-ranking" woman in AIM at the time, she had been

shot execution style in mid-December 1975 and left in a far corner of

the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation after having been kidnapped from Denver, Colorado and interrogated in Rapid City, South Dakota,

as a possible FBI informant. Means implicated Clyde Bellecourt in her

murder as well, and other AIM activists, including Theresa Rios. Means

said that part of the dissension within AIM in the early 1990s had

related to actions to expel the Bellecourt brothers for their part in

the Aquash execution; the organization split apart.

Earlier that day in a telephone interview with the journalists Paul

DeMain and Harlan McKosato about the upcoming press conference, Minnie Two Shoes had said, speaking of the importance of Aquash:

Part of why she was so important is because she was very symbolic, she was a hard working woman, she dedicated her life to the movement, to righting all the injustices that she could, and to pick somebody out and launch their little cointelpro program on her to bad jacket her to the point where she ends up dead, whoever did it, let's look at what the reasons are, you know, she was killed and lets look at the real reasons why it could have been any of us, it could have been me, it could have been, ya gotta look at the basically thousands of women, you gotta remember that it was mostly women in AIM, it could have been any one of us and I think that's why it's been so important and she was just such a good person.

McKosato said that "her [Aquash's] death has divided the American Indian Movement". On 4 November 1999, in a follow-up show on Native American Calling the next day, Vernon Bellecourt denied any involvement by him and his brother in the death of Aquash.

At Federal grand jury hearings in 2003, the Indian men Arlo Looking Cloud and John Graham were indicted for shooting Aquash in December 1975. In February '04, Arlo Looking Cloud was convicted of murder in Rapid City. He named as the gunman John Graham, who was in the Yukon. After extradition, John Graham

was convicted, in 2010 in Rapid City, of the murder. In both trials,

hearsay testimony about the motive for the murder included statements

that Aquash heard Leonard Peltier say he killed the FBI agents at Oglala in June 1975, and fear that Aquash could be working with the FBI. Peltier was convicted in 1976 of murder for the Oglala killings, on other evidence.