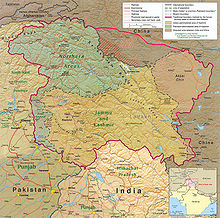

Political map of the Kashmir region districts, showing the Pir Panjal range and the Kashmir Valley or Vale of Kashmir.

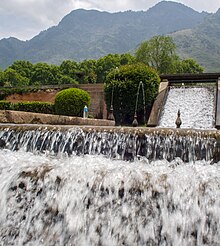

Pahalgam Valley, Kashmir.

Nanga Parbat in Kashmir, the ninth-highest mountain on Earth, is the western anchor of the Himalayas.

The Karakash River (Black Jade River) which flows north from its source near the town of Sumde in Aksai Chin, to cross the Kunlun Mountains.

Kashmir is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, it denotes a larger area that includes the Indian-administered territory of Jammu and Kashmir (which includes the divisions Jammu, Kashmir Valley, and Ladakh), the Pakistani-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, and Chinese-administered territories of Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract.

In the first half of the 1st millennium, the Kashmir region became an important centre of Hinduism and later of Buddhism; later still, in the ninth century, Kashmir Shaivism arose. In 1339, Shah Mir became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir, inaugurating the Salatin-i-Kashmir or Shah Mir dynasty. Kashmir was part of the Mughal Empire from 1586 to 1751, and thereafter, until 1820, of the Afghan Durrani Empire. That year, the Sikhs, under Ranjit Singh, annexed Kashmir. In 1846, after the Sikh defeat in the First Anglo-Sikh War, and upon the purchase of the region from the British under the Treaty of Amritsar, the Raja of Jammu, Gulab Singh, became the new ruler of Kashmir. The rule of his descendants, under the paramountcy (or tutelage) of the British Crown, lasted until the partition of India in 1947, when the former princely state of the British Indian Empire became a disputed territory, now administered by three countries: India, Pakistan, and China.

Etymology

The word Kashmir was derived from the ancient Sanskrit language and was referred to as káśmīra. The Nilamata Purana describes the Valley's origin from the waters, a lake called Sati-saras. A popular, but uncertain, local etymology of Kashmira is that it is land desiccated from water.

An alternative, but also uncertain, etymology derives the name from the name of the Hindu sage Kashyapa who is believed to have settled people in this land. Accordingly, Kashmir would be derived from either kashyapa-mir (Kashyapa's Lake) or kashyapa-meru (Kashyapa's Mountain).

The word has been referenced to in a Hindu scripture mantra worshipping the Hindu goddess Sharada and is mentioned to have resided in the land of kashmira,or which might have been a reference to the Sharada Peeth.

The Ancient Greeks called the region Kasperia which has been identified with Kaspapyros of Hecataeus of Miletus (apud Stephanus of Byzantium) and Kaspatyros of Herodotus (3.102, 4.44). Kashmir is also believed to be the country meant by Ptolemy's Kaspeiria. The earliest text which directly mentions the name Kashmir is in Ashtadhyayi written by a Sanskrit grammarian Pāṇini during 5th century BC. Pāṇini called the people of Kashmir as Kashmirikas. Some other early references to Kashmir can also be found in Mahabharata in Sabha Parva and in puranas like Matsya Purana, Vayu Purana, Padma Purana and Vishnu Purana and Vishnudharmottara Purana.

Huientsang, the Buddhist scholar and Chinese traveller called Kashmir as kia-shi-milo, while some other Chinese accounts referred Kashmir as ki-pin and ache-pin.

Cashmere is an archaic spelling of present-Kashmir, and in some countries it is still spelled this way.

In the Kashmiri language, Kashmir itself is known as Kasheer.

History

Hinduism and Buddhism in Kashmir

This general view of the unexcavated Buddhist stupa near Baramulla, with two figures standing on the summit, and another at the base with measuring scales, was taken by John Burke in 1868. The stupa, which was later excavated, dates to 500 CE.

During ancient and medieval period, Kashmir has been an important centre for the development of a Hindu-Buddhist syncretism, in which Madhyamaka and Yogachara were blended with Shaivism and Advaita Vedanta. The Buddhist Mauryan emperor Ashoka is often credited with having founded the old capital of Kashmir, Shrinagari, now ruins on the outskirts of modern Srinagar. Kashmir was long to be a stronghold of Buddhism. As a Buddhist seat of learning, the Sarvastivada school strongly influenced Kashmir. East and Central Asian Buddhist monks are recorded as having visited the kingdom. In the late 4th century CE, the famous Kuchanese monk Kumārajīva, born to an Indian noble family, studied Dīrghāgama

and Madhyāgama in Kashmir under Bandhudatta. He later became a prolific

translator who helped take Buddhism to China. His mother Jīva is

thought to have retired to Kashmir. Vimalākṣa, a Sarvāstivādan Buddhist

monk, travelled from Kashmir to Kucha and there instructed Kumārajīva in

the Vinayapiṭaka.

Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya. The temple complex was built by the third ruler of the Karkota dynasty, Emperor Lalitaditya Muktapida, in the 8th century CE. It is one of the largest temple complexes on the Indian subcontinent.

Ruins of the Martand Sun Temple. The temple was completely destroyed on the orders of Muslim Sultan Sikandar Butshikan in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year.

Karkoṭa Empire (625 CE – 885 CE) was a powerful Hindu empire, which originated in the region of Kashmir. It was founded by Durlabhvardhana during the lifetime of Harsha. The dynasty marked the rise of Kashmir as a power in South Asia. Avanti Varman ascended the throne of Kashmir on 855 CE, establishing the Utpala dynasty and ending the rule of Karkoṭa dynasty.

According to tradition, Adi Shankara visited the pre-existing Sarvajñapīṭha (Sharada Peeth) in Kashmir in the late 8th century or early 9th century CE. The Madhaviya Shankaravijayam states this temple had four doors for scholars from the four cardinal directions. The southern door of Sarvajna Pitha was opened by Adi Shankara.

According to tradition, Adi Shankara opened the southern door by

defeating in debate all the scholars there in all the various scholastic

disciplines such as Mīmāṃsā, Vedanta and other branches of Hindu philosophy; he ascended the throne of Transcendent wisdom of that temple.

Abhinavagupta (c. 950–1020 CE) was one of India's greatest philosophers, mystics and aestheticians. He was also considered an important musician, poet, dramatist, exegete, theologian, and logician – a polymathic personality who exercised strong influences on Indian culture. He was born in the Kashmir Valley

in a family of scholars and mystics and studied all the schools of

philosophy and art of his time under the guidance of as many as fifteen

(or more) teachers and gurus. In his long life he completed over 35 works, the largest and most famous of which is Tantrāloka, an encyclopaedic treatise on all the philosophical and practical aspects of Trika and Kaula (known today as Kashmir Shaivism). Another one of his very important contributions was in the field of philosophy of aesthetics with his famous Abhinavabhāratī commentary of Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata Muni.

In the 10th century Mokshopaya or Moksopaya Shastra, a philosophical text on salvation for non-ascetics (moksa-upaya: 'means to release'), was written on the Pradyumna hill in Srinagar. It has the form of a public sermon and claims human authorship and contains about 30,000 shloka's (making it longer than the Ramayana). The main part of the text forms a dialogue between Vashistha and Rama, interchanged with numerous short stories and anecdotes to illustrate the content. This text was later (11th to the 14th century CE) expanded and vedanticised, which resulted in the Yoga Vasistha.

Queen Kota Rani

was medieval Hindu ruler of Kashmir, ruling until 1339. She was a

notable ruler who is often credited for saving Srinagar city from

frequent floods by getting a canal constructed, named after her "Kutte Kol". This canal receives water from Jhelum River at the entry point of city and again merges with Jhelum river beyond the city limits.

Shah Mir Dynasty

Gateway of enclosure, (once a Hindu temple) of Zein-ul-ab-ud-din's Tomb, in Srinagar. Probable date 400 to 500 CE, 1868. John Burke. Oriental and India Office Collection. British Library.

Shams-ud-Din Shah Mir (reigned 1339–42) was the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir and founder of the Shah Mir dynasty. Kashmiri historian Jonaraja, in his Dvitīyā Rājataraṅginī mentioned Shah Mir was from the country of Panchagahvara (identified as the Panjgabbar valley between Rajouri and Budhal), and his ancestors were Kshatriya, who converted to Islam. Scholar A. Q. Rafiqi states:

Shāh Mīr arrived in Kashmir in 1313, along with his family, during the reign of Sūhadeva (1301–20), whose service he entered. In subsequent years, through his tact and ability, Shāh Mīr rose to prominence and became one of the important personalities of the time. Later, after the death in 1338 of Udayanadeva, the brother of Sūhadeva, he was able to assume the kingship himself and thus laid the foundation of permanent Muslim rule in Kashmir. Dissensions among the ruling classes and foreign invasions were the two main factors which contributed towards the establishment of Muslim rule in Kashmir.

Rinchan, from Ladakh, and Lankar Chak, from Dard territory near Gilgit, came to Kashmir and played a notable role in the subsequent political history of the Valley. All the three men were granted Jagirs (feudatory estates) by the King. Rinchan became the ruler of Kashmir for three years.

Shah Mir was the first ruler of Shah Mir dynasty, which had established in 1339 CE. Muslim ulama, such as Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, arrived from Central Asia to proselytize in Kashmir and their efforts converted thousands of Kashmiris to Islam and Hamadani's son also convinced Sikander Butshikan to enforce Islamic law. By the late 1400s most Kashmiris had accepted Islam.

Persian was introduced in Kashmir by the Šāh-Miri dynasty (1349-1561)

and started to flourish under Sultan Zayn-al-ʿĀbedin (1420-70).

Mughal rule

Nishat Bagh, a Mughal Garden built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in Srinagar, Kashmir

The Mughal padishah (emperor) Akbar conquered Kashmir from 1585-86, taking advantage of Kashmir's internal Sunni-Shia divisions, and thus ended indigenous Kashmiri Muslim rule. Akbar added it to the Kabul Subah (encompassing modern-day northeastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan and the Kashmir Valley of India), but Shah Jahan carved it out as a separate subah (imperial top-level province) with its seat at Srinagar.

Kashmir became the northern-most region of Mughal India as well as a

pleasure ground in the summertime. They built Persian water-gardens in

Srinagar, along the shores of Dal Lake, with cool and elegantly

proportioned terraces, fountains, roses, jasmine and rows of chinar

trees.

Afghan rule

Coin of Timur Shah Durrani (r. 1772–1793), minted in Kashmir, dated 1787

The Afghan Durrani dynasty's Durrani Empire controlled Kashmir from 1751, when weakling 15th Mughal padshah (emperor) Ahmad Shah Bahadur's viceroy Muin-ul-Mulk was defeated and reinstated by the Durrani founder Ahmad Shah Durrani

(who conquered, roughly, modern day Afghanistan and Pakistan from the

Mughals and local rulers), until the 1820 Sikh triumph. The Afghan

rulers brutally repressed Kashmiris of all faiths (according to Kashmiri

historians).

Sikh rule

In 1819, the Kashmir Valley passed from the control of the Durrani Empire of Afghanistan to the conquering armies of the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh of the Punjab, thus ending four centuries of Muslim rule under the Mughals and the Afghan regime. As the Kashmiris had suffered under the Afghans, they initially welcomed the new Sikh rulers. However, the Sikh governors turned out to be hard taskmasters, and Sikh rule was generally considered oppressive, protected perhaps by the remoteness of Kashmir from the capital of the Sikh Empire in Lahore. The Sikhs enacted a number of anti-Muslim laws, which included handing out death sentences for cow slaughter, closing down the Jamia Masjid in Srinagar, and banning the adhan, the public Muslim call to prayer.

Kashmir had also now begun to attract European visitors, several of

whom wrote of the abject poverty of the vast Muslim peasantry and of the

exorbitant taxes under the Sikhs.

High taxes, according to some contemporary accounts, had depopulated

large tracts of the countryside, allowing only one-sixteenth of the

cultivable land to be cultivated. Many Kashmiri peasants migrated to the plains of the Punjab.

However, after a famine in 1832, the Sikhs reduced the land tax to half

the produce of the land and also began to offer interest-free loans to

farmers; Kashmir became the second highest revenue earner for the Sikh Empire. During this time Kashmiri shawls became known worldwide, attracting many buyers, especially in the West.

The state of Jammu,

which had been on the ascendant after the decline of the Mughal Empire,

came under the sway of the Sikhs in 1770. Further in 1808, it was fully

conquered by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Gulab Singh, then a youngster in

the House of Jammu, enrolled in the Sikh troops and, by distinguishing

himself in campaigns, gradually rose in power and influence. In 1822, he

was anointed as the Raja of Jammu. Along with his able general Zorawar Singh Kahluria, he conquered and subdued Rajouri (1821), Kishtwar (1821), Suru valley and Kargil (1835), Ladakh (1834–1840), and Baltistan (1840), thereby surrounding the Kashmir Valley. He became a wealthy and influential noble in the Sikh court.

Princely state

1909 Map of the Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu. The names of regions, important cities, rivers, and mountains are underlined in red.

In 1845, the First Anglo-Sikh War broke out. According to The Imperial Gazetteer of India,

"Gulab Singh contrived to hold himself aloof till the battle of Sobraon (1846), when he appeared as a useful mediator and the trusted advisor of Sir Henry Lawrence. Two treaties were concluded. By the first the State of Lahore (i.e. West Punjab) handed over to the British, as equivalent for one crore indemnity, the hill countries between the rivers Beas and Indus; by the second the British made over to Gulab Singh for 75 lakhs all the hilly or mountainous country situated to the east of the Indus and the west of the Ravi i.e. the Vale of Kashmir)."

Drafted by a treaty and a bill of sale, and constituted between 1820 and 1858, the Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu (as it was first called) combined disparate regions, religions, and ethnicities: to the east, Ladakh was ethnically and culturally Tibetan

and its inhabitants practised Buddhism; to the south, Jammu had a mixed

population of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs; in the heavily populated

central Kashmir valley, the population was overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim, however, there was also a small but influential Hindu minority, the Kashmiri brahmins or pandits; to the northeast, sparsely populated Baltistan had a population ethnically related to Ladakh, but which practised Shia Islam; to the north, also sparsely populated, Gilgit Agency, was an area of diverse, mostly Shi'a groups; and, to the west, Punch was Muslim, but of different ethnicity than the Kashmir valley. After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, in which Kashmir sided with the British, and the subsequent assumption of direct rule by Great Britain, the princely state of Kashmir came under the suzerainty of the British Crown.

In the British census of India of 1941, Kashmir registered a

Muslim majority population of 77%, a Hindu population of 20% and a

sparse population of Buddhists and Sikhs comprising the remaining 3%. That same year, Prem Nath Bazaz, a Kashmiri Pandit

journalist wrote: “The poverty of the Muslim masses is appalling. ...

Most are landless laborers, working as serfs for absentee [Hindu]

landlords ... Almost the whole brunt of official corruption is borne by

the Muslim masses.”

Under the Hindu rule, Muslims faced hefty taxation, discrimination in

the legal system and were forced into labor without any wages. Conditions in the princely state caused a significant migration of people from the Kashmir Valley to Punjab of British India. For almost a century until the census, a small Hindu elite had ruled over a vast and impoverished Muslim peasantry.

Driven into docility by chronic indebtedness to landlords and

moneylenders, having no education besides, nor awareness of rights, the Muslim peasants had no political representation until the 1930s.

1947 and 1948

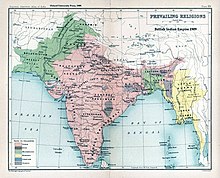

The prevailing religions by district in the 1901 Census of the Indian Empire.

Ranbir Singh's grandson Hari Singh,

who had ascended the throne of Kashmir in 1925, was the reigning

monarch in 1947 at the conclusion of British rule of the subcontinent

and the subsequent partition of the British Indian Empire into the newly independent Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan.

In the run up to 1947 partition, there were two major parties in the princely state: the National Conference and the Muslim Conference. The former was led by the charismatic Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah, who tilted towards the accession of the state to India, whilst the latter tilted towards accession to Pakistan.

The National Conference enjoyed popular support in the Kashmir Valley

whilst the Muslim Conference was more popular in the Jammu region. The Hindus and Sikhs of the state were firmly in favour of joining India, as were the Buddhists. However, the sentiments of the state's Muslim population were divided. Scholar Christopher Snedden

states that the Muslims of Western Jammu, and also the Muslims of the

Frontier Districts Province, strongly wanted Jammu and Kashmir to join

Pakistan. The ethnic Kashmiri Muslims of the Kashmir Valley, on the other hand, were ambivalent about Pakistan (possibly due to their secular nature). The fact that Kashmiris were not particularly enamoured with the idea of Pakistan reflected the failure of the idea of Pan-Islamic identity in satisfying the political urges of Kashmiris. At the same time there was also a lack of interest in merging with Indian nationalism.

According to Burton Stein's History of India,

"Kashmir was neither as large nor as old an independent state as Hyderabad; it had been created rather off-handedly by the British after the first defeat of the Sikhs in 1846, as a reward to a former official who had sided with the British. The Himalayan kingdom was connected to India through a district of the Punjab, but its population was 77 per cent Muslim and it shared a boundary with Pakistan. Hence, it was anticipated that the maharaja would accede to Pakistan when the British paramountcy ended on 14–15 August. When he hesitated to do this, Pakistan launched a guerrilla onslaught meant to frighten its ruler into submission. Instead the Maharaja appealed to Mountbatten for assistance, and the governor-general agreed on the condition that the ruler accede to India. Indian soldiers entered Kashmir and drove the Pakistani-sponsored irregulars from all but a small section of the state. The United Nations was then invited to mediate the quarrel. The UN mission insisted that the opinion of Kashmiris must be ascertained, while India insisted that no referendum could occur until all of the state had been cleared of irregulars."

In the last days of 1948, a ceasefire was agreed under UN auspices. However, since the referendum demanded by the UN was never conducted, relations between India and Pakistan soured, and eventually led to two more wars over Kashmir in 1965 and 1999.

Topographic map of Kashmir

Current status and political divisions

India has control of about half the area of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which continues the name Jammu and Kashmir, while Pakistan controls a third of the region, divided into two de facto provinces, Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir.

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "Although there

was a clear Muslim majority in Kashmir before the 1947 partition and its

economic, cultural, and geographic contiguity with the Muslim-majority

area of the Punjab (in Pakistan) could be convincingly demonstrated, the

political developments during and after the partition resulted in a

division of the region. Pakistan was left with territory that, although

basically Muslim in character, was thinly populated, relatively

inaccessible, and economically underdeveloped. The largest Muslim group,

situated in the Valley of Kashmir and estimated to number more than

half the population of the entire region, lay in Indian-administered

territory, with its former outlets via the Jhelum valley route blocked."

The eastern region of the former princely state of Kashmir is

also involved in a boundary dispute that began in the late 19th century

and continues into the 21st. Although some boundary agreements were

signed between Great Britain, Afghanistan and Russia over the northern

borders of Kashmir, China never accepted these agreements, and China's

official position has not changed following the communist revolution of 1949 that established the People's Republic of China. By the mid-1950s the Chinese army had entered the north-east portion of Ladakh:

- "By 1956–57 they had completed a military road through the Aksai Chin area to provide better communication between Xinjiang and western Tibet. India's belated discovery of this road led to border clashes between the two countries that culminated in the Sino-Indian war of October 1962."

The region is divided amongst three countries in a territorial dispute:

Pakistan controls the northwest portion (Northern Areas and Kashmir),

India controls the central and southern portion (Jammu and Kashmir) and

Ladakh, and the People's Republic of China controls the northeastern

portion (Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract). India controls the

majority of the Siachen Glacier area, including the Saltoro Ridge passes, whilst Pakistan controls the lower territory just southwest of the Saltoro Ridge. India controls 101,338 km2 (39,127 sq mi) of the disputed territory, Pakistan controls 85,846 km2 (33,145 sq mi), and the People's Republic of China controls the remaining 37,555 km2 (14,500 sq mi).

Jammu and Azad Kashmir lie outside Pir Panjal range, and are under Indian and Pakistani control respectively. These are populous regions. Gilgit–Baltistan, formerly known as the Northern Areas, is a group of territories in the extreme north, bordered by the Karakoram, the western Himalayas, the Pamir, and the Hindu Kush ranges. With its administrative centre in the town of Gilgit,

the Northern Areas cover an area of 72,971 square kilometres

(28,174 sq mi) and have an estimated population approaching 1 million

(10 lakhs).

Ladakh is a region in the east, between the Kunlun mountain range in the north and the main Great Himalayas to the south. Main cities are Leh and Kargil.

It is under Indian administration and is part of the state of Jammu and

Kashmir. It is one of the most sparsely populated regions in the area

and is mainly inhabited by people of Indo-Aryan and Tibetan descent. Aksai Chin is a vast high-altitude desert of salt that reaches altitudes up to 5,000 metres (16,000 ft). Geographically part of the Tibetan Plateau, Aksai Chin is referred to as the Soda Plain. The region is almost uninhabited, and has no permanent settlements.

Though these regions are in practice administered by their

respective claimants, neither India nor Pakistan has formally recognised

the accession of the areas claimed by the other. India claims those

areas, including the area "ceded" to China by Pakistan in the Trans-Karakoram Tract

in 1963, are a part of its territory, while Pakistan claims the entire

region excluding Aksai Chin and Trans-Karakoram Tract. The two countries

have fought several declared wars over the territory. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

established the rough boundaries of today, with Pakistan holding

roughly one-third of Kashmir, and India one-half, with a dividing line

of control established by the United Nations. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 resulted in a stalemate and a UN-negotiated ceasefire.

Demographics

In the 1901 Census of the British Indian Empire, the population of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu was 2,905,578. Of these, 2,154,695 (74.16%) were Muslims, 689,073 (23.72%) Hindus, 25,828 (0.89%) Sikhs, and 35,047 (1.21%) Buddhists (implying 935 (0.032%) others).

A Muslim shawl-making family shown in Cashmere shawl manufactory, 1867, chromolith., William Simpson.

A group of Kashmiri Pandits, natives of Kashmir Valley belong to one of the prominent Shaiva sects of Hinduism, shown in 1895.

Among the Muslims of the Kashmir province within the princely

state, four divisions were recorded: "Shaikhs, Saiyids, Mughals, and

Pathans. The Shaikhs, who are by far the most numerous, are the

descendants of Hindus, but have retained none of the caste rules of

their forefathers. They have clan names known as krams ..." These kram names included "Tantre", "Shaikh", "Bat", "Manto", "Ganai", "Dar", "Lon", "Wani" etc. The Saiyids

"could be divided into those who follow the profession of religion and

those who have taken to agriculture and other pursuits. Their kram

name is 'Mir.' While a Saiyid retains his saintly profession Mir is a

prefix; if he has taken to agriculture, Mir is an affix to his name." The Mughals who were not numerous had kram

names like "Mir" (a corruption of "Mirza"), "Beg", "Bandi", "Bach" and

"Ashaye". Finally, it was recorded that the Pathans "who are more

numerous than the Mughals, ... are found chiefly in the south-west of

the valley, where Pathan

colonies have from time to time been founded. The most interesting of

these colonies is that of Kuki-Khel Afridis at Dranghaihama, who retain

all the old customs and speak Pashto."

Among the main tribes of Muslims in the princely state are the Butts,

Dar, Lone, Jat, Gujjar, Rajput, Sudhan and Khatri. Some Kashmiri

families belonging to Butt, Lone and Wani/Wain clans use the title of

Khawaja which was given to them by Mughal governors as these families

were associated with Mughal Darbar. The Khatri use the title Shaikh and

the Gujjar use the title Chaudhary. All these tribes are indigenous to

the princely state which converted to Islam from Hinduism during its

arrival in the region.

The Hindus were found mainly in Jammu, where they constituted a little less than 60% of the population. In the Kashmir Valley, the Hindus represented "524 in every 10,000 of the population (i.e. 5.24%), and in the frontier wazarats of Ladhakh and Gilgit only 94 out of every 10,000 persons (0.94%)."

In the same Census of 1901, in the Kashmir Valley, the total population

was recorded to be 1,157,394, of which the Muslim population was

1,083,766, or 93.6% and the Hindu population 60,641. Among the Hindus of Jammu

province, who numbered 626,177 (or 90.87% of the Hindu population of

the princely state), the most important castes recorded in the census

were "Brahmans (186,000), the Rajputs (167,000), the Khattris (48,000) and the Thakkars (93,000)."

In the 1911 Census of the British Indian Empire, the total population of Kashmir and Jammu

had increased to 3,158,126. Of these, 2,398,320 (75.94%) were Muslims,

696,830 (22.06%) Hindus, 31,658 (1%) Sikhs, and 36,512 (1.16%) Buddhists.

In the last census of British India in 1941, the total population of

Kashmir and Jammu (which as a result of the second world war, was

estimated from the 1931 census) was 3,945,000. Of these, the total

Muslim population was 2,997,000 (75.97%), the Hindu population was

808,000 (20.48%), and the Sikh 55,000 (1.39%).

The Kashmiri Pandits,

the only Hindus of the Kashmir valley, who had stably constituted

approximately 4 to 5% of the population of the valley during Dogra rule

(1846–1947), and 20% of whom had left the Kashmir valley by 1950,

began to leave in much greater numbers in the 1990s. According to a

number of authors, approximately 100,000 of the total Kashmiri Pandit

population of 140,000 left the valley during that decade. Other authors have suggested a higher figure for the exodus, ranging from the entire population of over 150 to 190 thousand (1.5 to 190,000) of a total Pandit population of 200 thousand (200,000) to a number as high as 300 thousand (300,000).

People in Jammu speak Hindi, Punjabi and Dogri, the Vale of

Kashmir speaks Kashmiri and the sparsely inhabited Ladakh region speaks

Tibetan and Balti.

The total population of India's division of Jammu and Kashmir is 12,541,302 and Pakistan's division of Kashmir is 2,580,000 and Gilgit-Baltistan is 870,347.

Economy

Srinagar, the largest city of Kashmir

Kashmir's economy is centred around agriculture.

Traditionally the staple crop of the valley was rice, which formed the

chief food of the people. In addition, Indian corn, wheat, barley and

oats were also grown. Given its temperate climate, it is suited for crops like asparagus,

artichoke, seakale, broad beans, scarletrunners, beetroot, cauliflower

and cabbage. Fruit trees are common in the valley, and the cultivated

orchards yield pears, apples, peaches, and cherries. The chief trees are deodar, firs and pines, chenar or plane, maple, birch and walnut, apple, cherry.

Historically, Kashmir became known worldwide when Cashmere wool

was exported to other regions and nations (exports have ceased due to

decreased abundance of the cashmere goat and increased competition from

China). Kashmiris are well adept at knitting and making Pashmina shawls, silk carpets, rugs, kurtas, and pottery. Saffron, too, is grown in Kashmir. Srinagar is known for its silver-work, papier-mâché, wood-carving, and the weaving of silk. The economy was badly damaged by the 2005 Kashmir earthquake

which, as of 8 October 2005, resulted in over 70,000 deaths in the

Pakistan-controlled part of Kashmir and around 1,500 deaths in Indian

controlled Kashmir.

Transport

Transport is predominantly by air or road vehicles in the region. Kashmir has a 135 km (84 mi) long modern railway

line that started in October 2009, and was last extended in 2013 and

connects Baramulla, in the western part of Kashmir, to Srinagar and Banihal. It is expected to link Kashmir to the rest of India after the construction of the railway line from Katra to Banihal is completed.