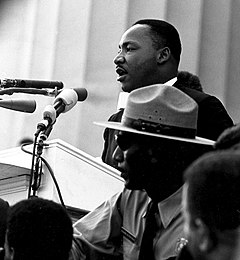

Martin Luther King Jr. delivering the speech at the 1963 Washington D.C. Civil Rights March.

"I Have a Dream" is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, in which he called for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States. Delivered to over 250,000 civil rights supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech was a defining moment of the civil rights movement and among the most iconic speeches in American history.

Beginning with a reference to the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed millions of slaves in 1863, King said "one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free". Toward the end of the speech, King departed from his prepared text for a partly improvised peroration on the theme "I have a dream", prompted by Mahalia Jackson's cry: "Tell them about the dream, Martin!"

In this part of the speech, which most excited the listeners and has

now become its most famous, King described his dreams of freedom and

equality arising from a land of slavery and hatred. Jon Meacham writes that, "With a single phrase, Martin Luther King Jr. joined Jefferson and Lincoln in the ranks of men who've shaped modern America". The speech was ranked the top American speech of the 20th century in a 1999 poll of scholars of public address.

Background

View from the Lincoln Memorial toward the Washington Monument on August 28, 1963

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was partly intended to demonstrate mass support for the civil rights legislation proposed by President Kennedy in June. Martin Luther King and other leaders therefore agreed to keep their speeches calm, also, to avoid provoking the civil disobedience which had become the hallmark of the Civil Rights Movement. King originally designed his speech as a homage to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, timed to correspond with the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Speech title and the writing process

King had been preaching about dreams since 1960, when he gave a speech to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) called "The Negro and the American Dream". This speech

discusses the gap between the American dream and reality, saying that

overt white supremacists

have violated the dream, and that "our federal government has also

scarred the dream through its apathy and hypocrisy, its betrayal of the

cause of justice". King suggests that "It may well be that the Negro is

God's instrument to save the soul of America."

In 1961, he spoke of the Civil Rights Movement and student activists'

"dream" of equality—"the American Dream ... a dream as yet

unfulfilled"—in several national speeches and statements, and took "the

dream" as the centerpiece for these speeches.

On November 27, 1962, King gave a speech at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount, North Carolina.

That speech was longer than the version which he would eventually

deliver from the Lincoln Memorial. And while parts of the text had been

moved around, large portions were identical, including the "I have a

dream" refrain. After being rediscovered, the restored and digitized recording of the 1962 speech was presented to the public by the English department of North Carolina State University.

King had also delivered a "dream" speech in Detroit, in June 1963, when he marched on Woodward Avenue with Walter Reuther and the Reverend C. L. Franklin, and had rehearsed other parts. Mahalia Jackson, who sang "How I Got Over", just before the speech in Washington, knew about King's Detroit speech.

The March on Washington Speech, known as "I Have a Dream Speech",

has been shown to have had several versions, written at several

different times.

It has no single version draft, but is an amalgamation of several

drafts, and was originally called "Normalcy, Never Again". Little of

this, and another "Normalcy Speech", ended up in the final draft. A

draft of "Normalcy, Never Again" is housed in the Morehouse College

Martin Luther King Jr. Collection of the Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University Center and Morehouse College. The focus on "I have a dream" comes through the speech's delivery. Toward the end of its delivery, noted African American gospel singer Mahalia Jackson shouted to King from the crowd, "Tell them about the dream, Martin."

King departed from his prepared remarks and started "preaching"

improvisationally, punctuating his points with "I have a dream."

The speech was drafted with the assistance of Stanley Levison and Clarence Benjamin Jones in Riverdale,

New York City. Jones has said that "the logistical preparations for the

march were so burdensome that the speech was not a priority for us" and

that, "on the evening of Tuesday, Aug. 27, [12 hours before the march]

Martin still didn't know what he was going to say".

Leading up to the speech's rendition at the Great March on

Washington, King had delivered its "I have a dream" refrains in his

speech before 25,000 people in Detroit's Cobo Hall immediately after the 125,000-strong Great Walk to Freedom in Detroit, June 23, 1963.

After the Washington, D.C. March, a recording of King's Cobo Hall

speech was released by Detroit's Gordy Records as an LP entitled "The

Great March To Freedom".

Speech

Widely hailed as a masterpiece of rhetoric, King's speech invokes pivotal documents in American history, including the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the United States Constitution. Early in his speech, King alludes to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address by saying "Five score years ago ..." In reference to the abolition of slavery

articulated in the Emancipation Proclamation, King says: "It came as a

joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity." Anaphora

(i.e., the repetition of a phrase at the beginning of sentences) is

employed throughout the speech. Early in his speech, King urges his

audience to seize the moment; "Now is the time" is repeated three times

in the sixth paragraph. The most widely cited example of anaphora is

found in the often quoted phrase "I have a dream", which is repeated

eight times as King paints a picture of an integrated and unified

America for his audience. Other occasions include "One hundred years

later", "We can never be satisfied", "With this faith", "Let freedom

ring", and "free at last". King was the sixteenth out of eighteen people

to speak that day, according to the official program.

I still have a dream, a dream deeply rooted in the American dream – one day this nation will rise up and live up to its creed, "We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal." I have a dream ...—Martin Luther King Jr. (1963)

Among the most quoted lines of the speech are "I have a dream that my

four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not

be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their

character. I have a dream today!"

According to U.S. Representative John Lewis, who also spoke that day as the president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee,

"Dr. King had the power, the ability, and the capacity to transform

those steps on the Lincoln Memorial into a monumental area that will

forever be recognized. By speaking the way he did, he educated, he

inspired, he informed not just the people there, but people throughout

America and unborn generations."

The ideas in the speech reflect King's social experiences of ethnocentric abuse, the mistreatment and exploitation of blacks.

The speech draws upon appeals to America's myths as a nation founded to

provide freedom and justice to all people, and then reinforces and

transcends those secular mythologies by placing them within a spiritual

context by arguing that racial justice is also in accord with God's

will. Thus, the rhetoric of the speech provides redemption to America

for its racial sins. King describes the promises made by America as a "promissory note"

on which America has defaulted. He says that "America has given the

Negro people a bad check", but that "we've come to cash this check" by

marching in Washington, D.C.

Similarities and allusions

King's speech used words and ideas from his own speeches and other texts. For years, he had spoken about dreams, quoted from Samuel Francis Smith's popular patriotic hymn "America" ("My Country, 'Tis of Thee"), and referred extensively to the Bible. The idea of constitutional rights as an "unfulfilled promise" was suggested by Clarence Jones.

The final passage from King's speech closely resembles Archibald Carey Jr.'s address to the 1952 Republican National Convention:

both speeches end with a recitation of the first verse of "America",

and the speeches share the name of one of several mountains from which

both exhort "let freedom ring".

King also is said to have used portions of Prathia Hall's speech at the site of a burned-down African American church in Terrell County, Georgia, in September 1962, in which she used the repeated phrase "I have a dream". The church burned down after it was used for voter registration meetings.

The speech also alludes to Psalm 30:5 in the second stanza of the speech. Additionally, King quotes from Isaiah 40:4–5 ("I have a dream that every valley shall be exalted ...") and Amos 5:24 ("But let justice roll down like water ..."). He also alludes to the opening lines of Shakespeare's Richard III

("Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer ...") when

he remarks that "this sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate

discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn ..."

Rhetoric

King at the Civil Rights March in Washington, D.C

The "I Have a Dream" speech can be dissected by using three rhetorical lenses: voice merging, prophetic voice, and dynamic spectacle.

Voice merging is the combining of one's own voice with religious

predecessors. Prophetic voice is using rhetoric to speak for a

population. A dynamic spectacle has origins from the Aristotelian

definition as "a weak hybrid form of drama, a theatrical concoction

that relied upon external factors (shock, sensation, and passionate

release) such as televised rituals of conflict and social control."

Voice merging is a common technique used amongst African American

preachers. It combines the voices of previous preachers and excerpts

from scriptures along with their own unique thoughts to create a unique

voice. King uses voice merging in his peroration when he references the secular hymn "America."

The rhetoric of King's speech can be compared to the rhetoric of Old Testament

prophets. During King's speech, he speaks with urgency and crisis

giving him a prophetic voice. The prophetic voice must "restore a sense

of duty and virtue amidst the decay of venality." An evident example is when King declares that, "now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children."

Why King's speech was powerful is debated, but essentially, it

came at a point of many factors combining at a key cultural turning

point. Executive speechwriter Anthony Trendl writes, "The right man

delivered the right words to the right people in the right place at the

right time."

"Given the context of drama and tension in which it was situated", King's speech can be classified as a dynamic spectacle.

A dynamic spectacle is dependent on the situation in which it is used.

It can be considered a dynamic spectacle because it happened at the

correct time and place: during the Civil Rights Movement and the March

on Washington.

Responses

The speech was lauded in the days after the event, and was widely

considered the high point of the March by contemporary observers. James Reston, writing for The New York Times,

said that "Dr. King touched all the themes of the day, only better than

anybody else. He was full of the symbolism of Lincoln and Gandhi, and

the cadences of the Bible. He was both militant and sad, and he sent the

crowd away feeling that the long journey had been worthwhile."

Reston also noted that the event "was better covered by television and

the press than any event here since President Kennedy's inauguration",

and opined that "it will be a long time before [Washington] forgets the

melodious and melancholy voice of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

crying out his dreams to the multitude." An article in The Boston Globe by Mary McGrory reported that King's speech "caught the mood" and "moved the crowd" of the day "as no other" speaker in the event. Marquis Childs of The Washington Post wrote that King's speech "rose above mere oratory". An article in the Los Angeles Times

commented that the "matchless eloquence" displayed by King—"a supreme

orator" of "a type so rare as almost to be forgotten in our age"—put to

shame the advocates of segregation by inspiring the "conscience of America" with the justice of the civil-rights cause.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation

(FBI), which viewed King and his allies for racial justice as

subversive, also noticed the speech. This provoked the organization to

expand their COINTELPRO operation against the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and to target King specifically as a major enemy of the United States. Two days after King delivered "I Have a Dream", Agent William C. Sullivan, the head of COINTELPRO, wrote a memo about King's growing influence:

In the light of King's powerful demagogic speech yesterday he stands head and shoulders above all other Negro leaders put together when it comes to influencing great masses of Negroes. We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.

The speech was a success for the Kennedy administration

and for the liberal civil rights coalition that had planned it. It was

considered a "triumph of managed protest", and not one arrest relating

to the demonstration occurred. Kennedy had watched King's speech on

television and been very impressed. Afterwards, March leaders accepted

an invitation to the White House to meet with President Kennedy. Kennedy

felt the March bolstered the chances for his civil rights bill.

Meanwhile, some of the more radical Black leaders who were present condemned the speech (along with the rest of the march) as too compromising. Malcolm X later wrote in his autobiography:

"Who ever heard of angry revolutionaries swinging their bare feet

together with their oppressor in lily pad pools, with gospels and

guitars and 'I have a dream' speeches?"

Legacy

The location on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial from which King delivered the speech is commemorated with this inscription

The March on Washington put pressure on the Kennedy administration to advance its civil rights legislation in Congress. The diaries of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.,

published posthumously in 2007, suggest that President Kennedy was

concerned that if the march failed to attract large numbers of

demonstrators, it might undermine his civil rights efforts.

In the wake of the speech and march, King was named Man of the Year by TIME magazine for 1963, and in 1964, he was the youngest person ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The full speech did not appear in writing until August 1983, some 15

years after King's death, when a transcript was published in The Washington Post.

In 1990, the Australian alternative comedy rock band Doug Anthony All Stars released an album called Icon. One song from Icon, "Shang-a-lang", sampled the end of the speech.

In 1992, the band Moodswings,

incorporated excerpts from Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream"

speech in their song "Spiritual High, Part III" on the album Moodfood.

In 2002, the Library of Congress honored the speech by adding it to the United States National Recording Registry. In 2003, the National Park Service dedicated an inscribed marble pedestal to commemorate the location of King's speech at the Lincoln Memorial.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

was dedicated in 2011. The centerpiece for the memorial is based on a

line from King's "I Have A Dream" speech: "Out of a mountain of despair,

a stone of hope."

A 30 feet (9.1 m)-high relief of King named the "Stone of Hope" stands

past two other pieces of granite that symbolize the "mountain of

despair."

In August 2012, the Dutch DJ and producer Bakermat released the single "One Day", which consists of an integrated sample of the speech. The re-release in 2014 became a hit in several European countries.

On August 26, 2013, UK's BBC Radio 4 broadcast "God's Trombone", in which Gary Younge looked behind the scenes of the speech and explored "what made it both timely and timeless".

On August 28, 2013, thousands gathered on the mall in Washington

D.C. where King made his historic speech to commemorate the 50th

anniversary of the occasion. In attendance were former U.S. Presidents Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter, and incumbent President Barack Obama, who addressed the crowd and spoke on the significance of the event. Many of King's family were in attendance.

On October 11, 2015, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution published an exclusive report about Stone Mountain

officials considering installation of a new "Freedom Bell" honoring

King and citing the speech's reference to the mountain "Let freedom ring

from Stone Mountain of Georgia."

Design details and a timeline for its installation remain to be

determined. The article mentioned inspiration for the proposed monument

came from a bell-ringing ceremony held in 2013 in celebration of the

50th anniversary of King's speech.

On April 20, 2016, Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew announced that the U.S. $5 bill,

which has featured the Lincoln Memorial on its back, would undergo a

redesign prior to 2020. Lew said that a portrait of Lincoln would

remain on the front of the bill, but the back would be redesigned to

depict various historical events that have occurred at the memorial,

including an image from King's speech.

Ava DuVernay was commissioned by the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture to create a film which debuted at the museum's opening on September 24, 2016. This film, August 28: A Day in the Life of a People (2016), tells of six significant events in African-American history that happened on the same date, August 28. Events depicted include (among others) the speech.

In October 2016, Science Friday in a segment on its crowd sourced update to the Voyager Golden Record included the speech.

Copyright dispute

Because King's speech was broadcast to a large radio and television

audience, there was controversy about its copyright status. If the

performance of the speech constituted "general publication", it would

have entered the public domain due to King's failure to register the speech with the Register of Copyrights. However, if the performance only constituted "limited publication", King retained common law copyright. This led to a lawsuit, Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. v. CBS, Inc., which established that the King estate does hold copyright over the speech and had standing to sue;

the parties then settled. Unlicensed use of the speech or a part of it

can still be lawful in some circumstances, especially in jurisdictions

under doctrines such as fair use or fair dealing. Under the applicable copyright laws, the speech will remain under copyright in the United States until 70 years after King's death, through 2038.

Original copy of the speech

As King waved goodbye to the audience, he handed George Raveling the original typewritten "I Have a Dream" speech. Raveling, a star Villanova Wildcats college basketball player, had volunteered as a security guard for the event and was on the podium with King at that moment.

In 2013, Raveling still had custody of the original copy, for which he

had been offered $3,000,000, but he has said he does not intend to sell

it.