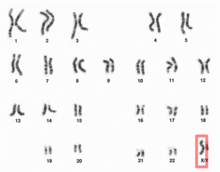

| Human Y chromosome | |

|---|---|

Human Y chromosome (after G-banding)

| |

Y chromosome in human male karyogram

| |

| Features | |

| Length (bp) | 57,227,415 bp (GRCh38) |

| No. of genes | 63 (CCDS) |

| Type | Allosome |

| Centromere position | Acrocentric (10.4 Mbp) |

| Complete gene lists | |

| CCDS | Gene list |

| HGNC | Gene list |

| UniProt | Gene list |

| NCBI | Gene list |

| External map viewers | |

| Ensembl | Chromosome Y |

| Entrez | Chromosome Y |

| NCBI | Chromosome Y |

| UCSC | Chromosome Y |

| Full DNA sequences | |

| RefSeq | NC_000024 (FASTA) |

| GenBank | CM000686 (FASTA) |

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or absence of Y that typically determines the male or female sex of offspring produced in sexual reproduction. In mammals, the Y chromosome contains the gene SRY, which by default triggers male development. The DNA in the human Y chromosome is composed of about 59 million base pairs. The Y chromosome is passed only from father to son. With a 30% difference between humans and chimpanzees, the Y chromosome is one of the fastest-evolving parts of the human genome. To date, over 200 Y-linked genes have been identified. All Y-linked genes are expressed and (apart from duplicated genes) hemizygous (present on only one chromosome) except in the cases of aneuploidy such as XYY syndrome or XXYY syndrome.

Overview

Discovery

The Y chromosome was identified as a sex-determining chromosome by Nettie Stevens at Bryn Mawr College in 1905 during a study of the mealworm Tenebrio molitor. Edmund Beecher Wilson

independently discovered the same mechanisms the same year. Stevens

proposed that chromosomes always existed in pairs and that the Y

chromosome was the pair of the X chromosome discovered in 1890 by Hermann Henking. She realized that the previous idea of Clarence Erwin McClung, that the X chromosome determines sex, was wrong and that sex determination

is, in fact, due to the presence or absence of the Y chromosome.

Stevens named the chromosome "Y" simply to follow on from Henking's "X"

alphabetically.

The idea that the Y chromosome was named after its similarity in

appearance to the letter "Y" is mistaken. All chromosomes normally

appear as an amorphous blob under the microscope and only take on a

well-defined shape during mitosis. This shape is vaguely X-shaped for all chromosomes. It is entirely coincidental that the Y chromosome, during mitosis, has two very short branches which can look merged under the microscope and appear as the descender of a Y-shape.

Variations

Most therian mammals have only one pair of sex chromosomes in each cell. Males have one Y chromosome and one X chromosome, while females have two X chromosomes. In mammals, the Y chromosome contains a gene, SRY,

which triggers embryonic development as a male. The Y chromosomes of

humans and other mammals also contain other genes needed for normal

sperm production.

There are exceptions, however. Among humans, some men have two Xs and a Y ("XXY", see Klinefelter syndrome), or one X and two Ys, and some women have three Xs or a single X instead of a double X. There are other exceptions in which SRY is damaged (leading to an XY female), or copied to the X (leading to an XX male).

Origins and evolution

Before Y chromosome

Many ectothermic vertebrates

have no sex chromosomes. If they have different sexes, sex is

determined environmentally rather than genetically. For some of them,

especially reptiles, sex depends on the incubation temperature; others are hermaphroditic (meaning they contain both male and female gametes in the same individual).

Origin

The X and Y chromosomes are thought to have evolved from a pair of identical chromosomes, termed autosomes, when an ancestral animal developed an allelic variation, a so-called "sex locus" – simply possessing this allele caused the organism to be male.

The chromosome with this allele became the Y chromosome, while the

other member of the pair became the X chromosome. Over time, genes that

were beneficial for males and harmful to (or had no effect on) females

either developed on the Y chromosome or were acquired through the

process of translocation.

Until recently, the X and Y chromosomes were thought to have diverged around 300 million years ago. However, research published in 2010, and particularly research published in 2008 documenting the sequencing of the platypus genome,

has suggested that the XY sex-determination system would not have been

present more than 166 million years ago, at the split of the monotremes from other mammals. This re-estimation of the age of the therian XY system is based on the finding that sequences that are on the X chromosomes of marsupials and eutherian mammals are present on the autosomes of platypus and birds. The older estimate was based on erroneous reports that the platypus X chromosomes contained these sequences.

Recombination inhibition

Recombination

between the X and Y chromosomes proved harmful—it resulted in males

without necessary genes formerly found on the Y chromosome, and females

with unnecessary or even harmful genes previously only found on the Y

chromosome. As a result, genes beneficial to males accumulated near the

sex-determining genes, and recombination in this region was suppressed

in order to preserve this male specific region.

Over time, the Y chromosome changed in such a way as to inhibit the

areas around the sex determining genes from recombining at all with the X

chromosome. As a result of this process, 95% of the human Y chromosome

is unable to recombine. Only the tips of the Y and X chromosomes

recombine. The tips of the Y chromosome that could recombine with the X

chromosome are referred to as the pseudoautosomal region. The rest of the Y chromosome is passed on to the next generation intact, allowing for its use in tracking human evolution.

Degeneration

By one estimate, the human Y chromosome has lost 1,393 of its 1,438 original genes over the course of its existence, and linear extrapolation of this 1,393-gene loss over 300 million years gives a rate of genetic loss of 4.6 genes per million years.

Continued loss of genes at the rate of 4.6 genes per million years

would result in a Y chromosome with no functional genes – that is the Y

chromosome would lose complete function – within the next 10 million

years, or half that time with the current age estimate of 160 million

years.

Comparative genomic analysis reveals that many mammalian species are

experiencing a similar loss of function in their heterozygous sex

chromosome. Degeneration may simply be the fate of all non-recombining

sex chromosomes, due to three common evolutionary forces: high mutation rate, inefficient selection, and genetic drift.

However, comparisons of the human and chimpanzee

Y chromosomes (first published in 2005) show that the human Y

chromosome has not lost any genes since the divergence of humans and

chimpanzees between 6–7 million years ago,

and a scientific report in 2012 stated that only one gene had been lost

since humans diverged from the rhesus macaque 25 million years ago.

These facts provide direct evidence that the linear extrapolation

model is flawed and suggest that the current human Y chromosome is

either no longer shrinking or is shrinking at a much slower rate than

the 4.6 genes per million years estimated by the linear extrapolation

model.

High mutation rate

The

human Y chromosome is particularly exposed to high mutation rates due

to the environment in which it is housed. The Y chromosome is passed

exclusively through sperm, which undergo multiple cell divisions during gametogenesis.

Each cellular division provides further opportunity to accumulate base

pair mutations. Additionally, sperm are stored in the highly oxidative

environment of the testis, which encourages further mutation. These two

conditions combined put the Y chromosome at a greater opportunity of

mutation than the rest of the genome. The increased mutation opportunity for the Y chromosome is reported by Graves as a factor 4.8.

However, her original reference obtains this number for the relative

mutation rates in male and female germ lines for the lineage leading to

humans.

The observation that the Y chromosome experiences little meiotic recombination and has an accelerated rate of mutation and degradative change compared to the rest of the genome suggests an evolutionary explanation for the adaptive function of meiosis with respect to the main body of genetic information. Brandeis

proposed that the basic function of meiosis (particularly meiotic

recombination) is the conservation of the integrity of the genome, a

proposal consistent with the idea that meiosis is an adaptation for repairing DNA damage.

Inefficient selection

Without the ability to recombine during meiosis, the Y chromosome is unable to expose individual alleles

to natural selection. Deleterious alleles are allowed to "hitchhike"

with beneficial neighbors, thus propagating maladapted alleles in to the

next generation. Conversely, advantageous alleles may be selected

against if they are surrounded by harmful alleles (background

selection). Due to this inability to sort through its gene content, the Y

chromosome is particularly prone to the accumulation of "junk" DNA. Massive accumulations of retrotransposable elements are scattered throughout the Y.

The random insertion of DNA segments often disrupts encoded gene

sequences and renders them nonfunctional. However, the Y chromosome has

no way of weeding out these "jumping genes". Without the ability to

isolate alleles, selection cannot effectively act upon them.

A clear, quantitative indication of this inefficiency is the entropy rate of the Y chromosome. Whereas all other chromosomes in the human genome

have entropy rates of 1.5–1.9 bits per nucleotide (compared to the

theoretical maximum of exactly 2 for no redundancy), the Y chromosome's

entropy rate is only 0.84. This means the Y chromosome has a much lower information content relative to its overall length; it is more redundant.

Genetic drift

Even

if a well adapted Y chromosome manages to maintain genetic activity by

avoiding mutation accumulation, there is no guarantee it will be passed

down to the next generation. The population size of the Y chromosome is

inherently limited to 1/4 that of autosomes: diploid organisms contain

two copies of autosomal chromosomes while only half the population

contains 1 Y chromosome. Thus, genetic drift is an exceptionally strong

force acting upon the Y chromosome. Through sheer random assortment, an

adult male may never pass on his Y chromosome if he only has female

offspring. Thus, although a male may have a well adapted Y chromosome

free of excessive mutation, it may never make it into the next gene

pool.

The repeat random loss of well-adapted Y chromosomes, coupled with the

tendency of the Y chromosome to evolve to have more deleterious

mutations rather than less for reasons described above, contributes to

the species-wide degeneration of Y chromosomes through Muller's ratchet.

Gene conversion

As it has been already mentioned, the Y chromosome is unable to recombine during meiosis like the other human chromosomes; however, in 2003, researchers from MIT discovered a process which may slow down the process of degradation.

They found that human Y chromosome is able to "recombine" with itself, using palindrome base pair sequences. Such a "recombination" is called gene conversion.

In the case of the Y chromosomes, the palindromes are not noncoding DNA;

these strings of bases contain functioning genes important for male

fertility. Most of the sequence pairs are greater than 99.97% identical.

The extensive use of gene conversion may play a role in the ability of

the Y chromosome to edit out genetic mistakes and maintain the integrity

of the relatively few genes it carries. In other words, since the Y

chromosome is single, it has duplicates of its genes on itself instead

of having a second, homologous, chromosome. When errors occur, it can

use other parts of itself as a template to correct them.

Findings were confirmed by comparing similar regions of the Y chromosome in humans to the Y chromosomes of chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas.

The comparison demonstrated that the same phenomenon of gene conversion

appeared to be at work more than 5 million years ago, when humans and

the non-human primates diverged from each other.

Future evolution

In

the terminal stages of the degeneration of the Y chromosome, other

chromosomes increasingly take over genes and functions formerly

associated with it. Finally, the Y chromosome disappears entirely, and a

new sex-determining system arises. Several species of rodent in the sister families Muridae and Cricetidae have reached these stages, in the following ways:

- The Transcaucasian mole vole, Ellobius lutescens, the Zaisan mole vole, Ellobius tancrei, and the Japanese spinous country rats Tokudaia osimensis and Tokudaia tokunoshimensis, have lost the Y chromosome and SRY entirely. Tokudaia spp. have relocated some other genes ancestrally present on the Y chromosome to the X chromosome. Both sexes of Tokudaia spp. and Ellobius lutescens have an XO genotype (Turner syndrome), whereas all Ellobius tancrei possess an XX genotype. The new sex-determining system(s) for these rodents remains unclear.

- The wood lemming Myopus schisticolor, the Arctic lemming, Dicrostonyx torquatus, and multiple species in the grass mouse genus Akodon have evolved fertile females who possess the genotype generally coding for males, XY, in addition to the ancestral XX female, through a variety of modifications to the X and Y chromosomes.

- In the creeping vole, Microtus oregoni, the females, with just one X chromosome each, produce X gametes only, and the males, XY, produce Y gametes, or gametes devoid of any sex chromosome, through nondisjunction.

Outside of the rodents, the black muntjac, Muntiacus crinifrons, evolved new X and Y chromosomes through fusions of the ancestral sex chromosomes and autosomes.

1:1 sex ratio

Fisher's principle outlines why almost all species using sexual reproduction have a sex ratio of 1:1. W. D. Hamilton gave the following basic explanation in his 1967 paper on "Extraordinary sex ratios", given the condition that males and females cost equal amounts to produce:

- Suppose male births are less common than female.

- A newborn male then has better mating prospects than a newborn female, and therefore can expect to have more offspring.

- Therefore, parents genetically disposed to produce males tend to have more than average numbers of grandchildren born to them.

- Therefore, the genes for male-producing tendencies spread, and male births become more common.

- As the 1:1 sex ratio is approached, the advantage associated with producing males dies away.

- The same reasoning holds if females are substituted for males throughout. Therefore, 1:1 is the equilibrium ratio.

Non-therian Y chromosome

Many

groups of organisms in addition to therian mammals have Y chromosomes,

but these Y chromosomes do not share common ancestry with therian Y

chromosomes. Such groups include monotremes, Drosophila, some other insects, some fish, some reptiles, and some plants. In Drosophila melanogaster, the Y chromosome does not trigger male development. Instead, sex is determined by the number of X chromosomes. The D. melanogaster Y chromosome does contain genes necessary for male fertility. So XXY D. melanogaster are female, and D. melanogaster with a single X (X0), are male but sterile. There are some species of Drosophila in which X0 males are both viable and fertile.

ZW chromosomes

Other

organisms have mirror image sex chromosomes: where the homogeneous sex

is the male, said to have two Z chromosomes, and the female is the

heterogeneous sex, and said to have a Z chromosome and a W chromosome. For example, female birds, snakes, and butterflies have ZW sex chromosomes, and males have ZZ sex chromosomes.

Non-inverted Y chromosome

There are some species, such as the Japanese rice fish,

the XY system is still developing and cross over between the X and Y is

still possible. Because the male specific region is very small and

contains no essential genes, it is even possible to artificially induce

XX males and YY females to no ill effect.

Multiple XY pairs

Monotremes possess four or five (platypus)

pairs of XY sex chromosomes, each pair consisting of sex chromosomes

with homologous regions. The chromosomes of neighboring pairs are

partially homologous, such that a chain is formed during mitosis.

The first X chromosome in the chain is also partially homologous with

the last Y chromosome, indicating that profound rearrangements, some

adding new pieces from autosomes, have occurred in history.

Platypus sex chromosomes have strong sequence similarity with the avian Z chromosome, (indicating close homology),

and the SRY gene so central to sex-determination in most other mammals

is apparently not involved in platypus sex-determination.

Human Y chromosome

In humans, the Y chromosome spans about 58 million base pairs (the building blocks of DNA) and represents approximately 1% of the total DNA in a male cell. The human Y chromosome contains over 200 genes, at least 72 of which code for proteins. Traits that are inherited via the Y chromosome are called Y-linked, or holandric traits.

Men can lose the Y chromosome in a subset of cells, which is called the mosaic loss of chromosome Y (LOY). This post-zygotic

mutation is strongly associated with age, affecting about 15% of men 70

years of age. Smoking is another important risk factor for LOY. It has been found that men with a higher percentage of hematopoietic stem cells in blood lacking the Y chromosome (and perhaps a higher percentage of other cells lacking it) have a higher risk of certain cancers

and have a shorter life expectancy. Men with LOY (which was defined as

no Y in at least 18% of their hematopoietic cells) have been found to

die 5.5 years earlier on average than others. This has been interpreted

as a sign that the Y chromosome plays a role going beyond sex

determination and reproduction

(although the loss of Y may be an effect rather than a cause). Male

smokers have between 1.5 and 2 times the risk of non-respiratory cancers

as female smokers.

Non-combining region of Y (NRY)

The human Y chromosome is normally unable to recombine with the X chromosome, except for small pieces of pseudoautosomal regions at the telomeres (which comprise about 5% of the chromosome's length). These regions are relics of ancient homology

between the X and Y chromosomes. The bulk of the Y chromosome, which

does not recombine, is called the "NRY", or non-recombining region of

the Y chromosome. The single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this region are used to trace direct paternal ancestral lines.

Genes

Number of genes

The following are some of the gene count estimates of human Y chromosome. Because researchers use different approaches to genome annotation their predictions of the number of genes on each chromosome varies (for technical details, see gene prediction). Among various projects, the collaborative consensus coding sequence project (CCDS)

takes an extremely conservative strategy. So CCDS's gene number

prediction represents a lower bound on the total number of human

protein-coding genes.

| Estimated by | Protein-coding genes | Non-coding RNA genes | Pseudogenes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCDS | 63 | — | — |

| HGNC | 45 | 55 | 381 |

| Ensembl | 63 | 109 | 392 |

| UniProt | 47 | — | — |

| NCBI | 73 | 122 | 400 |

Gene list

In general, the human Y chromosome is extremely gene poor—it is one of the largest gene deserts in the human genome. Disregarding pseudoautosomal genes, genes encoded on the human Y chromosome include:

- NRY, with corresponding gene on X chromosome

- NRY, other

- AZF1 (azoospermia factor 1)

- BPY2 (basic protein on the Y chromosome)

- DAZ1 (deleted in azoospermia)

- DAZ2

- DFNY1 encoding protein Deafness, Y-linked 1

- PRKY (protein kinase, Y-linked)

- RBMY1A1

- SRY (sex-determining region)

- TSPY (testis-specific protein)

- USP9Y

- UTY (ubiquitously transcribed TPR gene on Y chromosome)

- ZFY (zinc finger protein)

Y-chromosome-linked diseases

Diseases linked to the Y chromosome typically involve an aneuploidy, an atypical number of chromosomes.

Y chromosome microdeletion

Y chromosome microdeletion

(YCM) is a family of genetic disorders caused by missing genes in the Y

chromosome. Many affected men exhibit no symptoms and lead normal

lives. However, YCM is also known to be present in a significant number

of men with reduced fertility or reduced sperm count.

Defective Y chromosome

This results in the person presenting a female phenotype (i.e., is born with female-like genitalia) even though that person possesses an XY karyotype. The lack of the second X results in infertility. In other words, viewed from the opposite direction, the person goes through defeminization but fails to complete masculinization.

The cause can be seen as an incomplete Y chromosome: the usual

karyotype in these cases is 45X, plus a fragment of Y. This usually

results in defective testicular development, such that the infant may or

may not have fully formed male genitalia internally or externally. The

full range of ambiguity of structure may occur, especially if mosaicism is present. When the Y fragment is minimal and nonfunctional, the child is usually a girl with the features of Turner syndrome or mixed gonadal dysgenesis.

XXY

Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY) is not an aneuploidy

of the Y chromosome, but a condition of having an extra X chromosome,

which usually results in defective postnatal testicular function. The

mechanism is not fully understood; it does not seem to be due to direct

interference by the extra X with expression of Y genes.

XYY

47, XYY syndrome (simply known as XYY syndrome) is caused by the

presence of a single extra copy of the Y chromosome in each of a male's

cells. 47, XYY males have one X chromosome and two Y chromosomes, for a

total of 47 chromosomes per cell. Researchers have found that an extra

copy of the Y chromosome is associated with increased stature and an

increased incidence of learning problems in some boys and men, but the

effects are variable, often minimal, and the vast majority do not know

their karyotype.

In 1965 and 1966 Patricia Jacobs and colleagues published a chromosome survey of 315 male patients at

Scotland's only special security hospital for the developmentally disabled,

finding a higher than expected number of patients to have an extra Y chromosome.

The authors of this study wondered "whether an extra Y chromosome

predisposes its carriers to unusually aggressive behaviour", and this

conjecture "framed the next fifteen years of research on the human Y

chromosome".

Through studies over the next decade, this conjecture was shown

to be incorrect: the elevated crime rate of XYY males is due to lower

median intelligence and not increased aggression, and increased height was the only characteristic that could be reliably associated with XYY males. The "criminal karyotype" concept is therefore inaccurate.

Rare

The following Y-chromosome-linked diseases are rare, but notable because of their elucidating of the nature of the Y chromosome.

More than two Y chromosomes

Greater

degrees of Y chromosome polysomy (having more than one extra copy of

the Y chromosome in every cell, e.g., XYYY) are rare. The extra genetic

material in these cases can lead to skeletal abnormalities, decreased

IQ, and delayed development, but the severity features of these

conditions are variable.

XX male syndrome

XX male syndrome occurs when there has been a recombination in the formation of the male gametes, causing the SRY

portion of the Y chromosome to move to the X chromosome. When such an X

chromosome contributes to the child, the development will lead to a

male, because of the SRY gene.

Genetic genealogy

In human genetic genealogy (the application of genetics to traditional genealogy),

use of the information contained in the Y chromosome is of particular

interest because, unlike other chromosomes, the Y chromosome is passed

exclusively from father to son, on the patrilineal line. Mitochondrial DNA, maternally inherited to both sons and daughters, is used in an analogous way to trace the matrilineal line.

Brain function

Research

is currently investigating whether male-pattern neural development is a

direct consequence of Y-chromosome-related gene expression or an

indirect result of Y-chromosome-related androgenic hormone production.

Microchimerism

The presence of male chromosomes in fetal cells in the blood circulation of women was discovered in 1974.

In 1996, it was found that male fetal progenitor cells could

persist postpartum in the maternal blood stream for as long as 27 years.

A 2004 study at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center,

Seattle, investigated the origin of male chromosomes found in the

peripheral blood of women who had not had male progeny. A total of 120

subjects (women who had never had sons) were investigated, and it was

found that 21% of them had male DNA. The subjects were categorised into

four groups based on their case histories:

- Group A (8%) had had only female progeny.

- Patients in Group B (22%) had a history of one or more miscarriages.

- Patients Group C (57%) had their pregnancies medically terminated.

- Group D (10%) had never been pregnant before.

The study noted that 10% of the women had never been pregnant before,

raising the question of where the Y chromosomes in their blood could

have come from. The study suggests that possible reasons for occurrence

of male chromosome microchimerism could be one of the following:

- miscarriages,

- pregnancies,

- vanished male twin,

- possibly from sexual intercourse.

A 2012 study at the same institute has detected cells with the Y chromosome in multiple areas of the brains of deceased