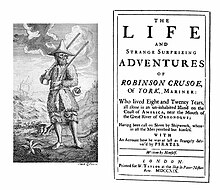

Front cover of the first edition, published by B. W. Huebsch in 1916

| |

| Author | James Joyce |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Künstlerroman, modernism |

| Set in | Dublin and Clongowes Wood College, c. 1890s |

| Published | 29 December 1916 |

| Publisher | B. W. Huebsch |

| Media type | Print: hardback |

| Pages | 299 |

| 823.912 | |

| LC Class | PR6019 .O9 |

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is the first novel of Irish writer James Joyce. A Künstlerroman in a modernist style, it traces the religious and intellectual awakening of young Stephen Dedalus, a fictional alter ego of Joyce and an allusion to Daedalus, the consummate craftsman of Greek mythology. Stephen questions and rebels against the Catholic and Irish conventions under which he has grown, culminating in his self-exile from Ireland to Europe. The work uses techniques that Joyce developed more fully in Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939).

A Portrait began life in 1904 as Stephen Hero—a projected 63-chapter autobiographical novel in a realistic style. After 25 chapters, Joyce abandoned Stephen Hero in 1907 and set to reworking its themes and protagonist into a condensed five-chapter novel, dispensing with strict realism and making extensive use of free indirect speech that allows the reader to peer into Stephen's developing consciousness. American modernist poet Ezra Pound had the novel serialised in the English literary magazine The Egoist in 1914 and 1915, and published as a book in 1916 by B. W. Huebsch of New York. The publication of A Portrait and the short story collection Dubliners (1914) earned Joyce a place at the forefront of literary modernism.

Background

James Joyce in 1915

Born into a middle-class family in Dublin, Ireland, James Joyce

(1882–1941) excelled as a student, graduating from University College,

Dublin, in 1902. He moved to Paris to study medicine, but soon gave it

up. He returned to Ireland at his family's request as his mother was

dying of cancer. Despite her pleas, the impious Joyce and his brother Stanislaus refused to make confession or take communion, and when she passed into a coma they refused to kneel and pray for her.

After a stretch of failed attempts to get published and launch his own

newspaper, Joyce then took jobs teaching, singing and reviewing books.

Joyce made his first attempt at a novel, Stephen Hero, in early 1904. That June he saw Nora Barnacle for the first time walking along Nassau Street. Their first date was on June 16, the same date that his novel Ulysses takes place.

Almost immediately, Joyce and Nora were infatuated with each other and

they bonded over their shared disapproval of Ireland and the Church. Nora and Joyce eloped to continental Europe, first staying in Zürich before settling for ten years in Trieste (then in Austria-Hungary),

where he taught English. In March 1905, Joyce was transferred to the

Berlitz School In Trieste, presumably because of threats of spies in

Austria.

There Nora gave birth to their children, George in 1905 and Lucia in

1907, and Joyce wrote fiction, signing some of his early essays and

stories "Stephen Daedalus". The short stories he wrote made up the

collection Dubliners (1914), which took about eight years to be published due to its controversial nature. While waiting on Dubliners to be published, Joyce reworked the core themes of the novel Stephen Hero he had begun in Ireland in 1904 and abandoned in 1907 into A Portrait, published in 1916, a year after he had moved back to Zürich in the midst of the First World War.

Composition

Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes.

("And he turned his mind to unknown arts.")

— Ovid, Epigraph to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

James Joyce in 1915

At the request of its editors, Joyce submitted a work of philosophical

fiction entitled "A Portrait of the Artist" to the Irish literary

magazine Dana on 7 January 1904. Dana's editor, W. K. Magee, rejected it, telling Joyce, "I can't print what I can't understand." On his 22nd birthday, 2 February 1904, Joyce began a realist autobiographical novel, Stephen Hero, which incorporated aspects of the aesthetic philosophy expounded in A Portrait.

He worked on the book until mid-1905 and brought the manuscript with

him when he moved to Trieste that year. Though his main attention turned

to the stories that made up Dubliners, Joyce continued work on Stephen Hero. At 914 manuscript pages, Joyce considered the book about half-finished, having completed 25 of its 63 intended chapters.

In September 1907, however, he abandoned this work, and began a

complete revision of the text and its structure, producing what became A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. By 1909 the work had taken shape and Joyce showed some of the draft chapters to Ettore Schmitz,

one of his language students, as an exercise. Schmitz, himself a

respected writer, was impressed and with his encouragement Joyce

continued work on the book.

In 1911 Joyce flew into a fit of rage over the continued refusals by publishers to print Dubliners and threw the manuscript of Portrait into the fire. It was saved by a "family fire brigade" including his sister Eileen. Chamber Music, a book of Joyce's poems, was published in 1907.

Joyce showed, in his own words, "a scrupulous meanness" in his use of materials for the novel. He recycled the two earlier attempts at explaining his aesthetics and youth, A Portrait of the Artist and Stephen Hero, as well as his notebooks from Trieste concerning the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas; they all came together in five carefully paced chapters.

Stephen Hero is written from the point of view of an omniscient third-person narrator, but in Portrait Joyce adopts the free indirect style,

a change that reflects the moving of the narrative centre of

consciousness firmly and uniquely onto Stephen. Persons and events take

their significance from Stephen, and are perceived from his point of

view.

Characters and places are no longer mentioned simply because the young

Joyce had known them. Salient details are carefully chosen and fitted

into the aesthetic pattern of the novel.

Publication history

Ezra Pound had A Portrait brought into print.

In 1913 the Irish poet W. B. Yeats recommended Joyce's work to the avant-garde American poet Ezra Pound, who was assembling an anthology of verse. Pound wrote to Joyce, and in 1914 Joyce submitted the first chapter of the unfinished Portrait to Pound, who was so taken with it that he pressed to have the work serialised in the London literary magazine The Egoist. Joyce hurried to complete the novel, and it appeared in The Egoist in twenty-five installments from 2 February 1914 to 1 September 1915.

There was difficulty finding a British publisher for the finished

novel, so Pound arranged for its publication by an American publishing

house, B. W. Huebsch, which issued it on 29 December 1916. The Egoist Press republished it in the United Kingdom on 12 February 1917 and Jonathan Cape took over its publication in 1924. In 1964 Viking Press issued a corrected version overseen by Chester Anderson. Garland released a "copy text" edition by Hans Walter Gabler in 1993.

Major characters

- Stephen Dedalus – The main character of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Growing up, Stephen goes through long phases of hedonism and deep religiosity. He eventually adopts a philosophy of aestheticism, greatly valuing beauty and art. Stephen is essentially Joyce's alter ego, and many of the events of Stephen's life mirror events from Joyce's own youth. His surname is taken from the ancient Greek mythical figure Daedalus, who also engaged in a struggle for autonomy.

- Simon Dedalus – Stephen's father, an impoverished former medical student with a strong sense of Irish nationalism. Sentimental about his past, Simon Dedalus frequently reminisces about his youth. Loosely based on Joyce's own father and their relationship.

- Mary Dedalus – Stephen's mother who is very religious and often argues with Stephen about attending services.

- Emma Clery – Stephen's beloved, the young girl to whom he is fiercely attracted over the course of many years. Stephen constructs Emma as an ideal of femininity, even though (or because) he does not know her well.

- Charles Stewart Parnell – An Irish political leader who is not an actual character in the novel, but whose death influences many of its characters. Parnell had powerfully led the Irish Parliamentary Party until he was driven out of public life after his affair with a married woman was exposed.

- Cranly – Stephen's best friend at university, in whom he confides some of his thoughts and feelings. In this sense Cranly represents a secular confessor for Stephen. Eventually Cranly begins to encourage Stephen to conform to the wishes of his family and to try harder to fit in with his peers, advice that Stephen fiercely resents. Towards the conclusion of the novel he bears witness to Stephen's exposition of his aesthetic philosophy. It is partly due to Cranly that Stephen decides to leave, after witnessing Cranly's budding (and reciprocated) romantic interest in Emma.

- Dante (Mrs. Riordan) – The governess of the Dedalus children. She is very intense and a dedicated Catholic.

- Lynch – Stephen's friend from university who has a rather dry personality.

Synopsis

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo ...

His father told him that story: his father looked at him through a glass: he had a hairy face.

He was baby tuckoo. The moocow came down the road where Betty Byrne lived: she sold lemon platt.

— James Joyce, Opening to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

The childhood of Stephen Dedalus is recounted using vocabulary that

changes as he grows, in a voice not his own but sensitive to his

feelings. The reader experiences Stephen's fears and bewilderment as he

comes to terms with the world in a series of disjointed episodes. Stephen attends the Jesuit-run Clongowes Wood College,

where the apprehensive, intellectually gifted boy suffers the ridicule

of his classmates while he learns the schoolboy codes of behaviour.

While he cannot grasp their significance, at a Christmas dinner he is

witness to the social, political and religious tensions in Ireland

involving Charles Stewart Parnell,

which drive wedges between members of his family, leaving Stephen with

doubts over which social institutions he can place his faith in.

Back at Clongowes, word spreads that a number of older boys have been

caught "smugging"; discipline is tightened, and the Jesuits increase use

of corporal punishment.

Stephen is strapped when one of his instructors believes he has broken

his glasses to avoid studying, but, prodded by his classmates, Stephen

works up the courage to complain to the rector, Father Conmee, who assures him there will be no such recurrence, leaving Stephen with a sense of triumph.

Stephen's father gets into debt and the family leaves its

pleasant suburban home to live in Dublin. Stephen realises that he will

not return to Clongowes. However, thanks to a scholarship obtained for

him by Father Conmee, Stephen is able to attend Belvedere College, where he excels academically and becomes a class leader.

Stephen squanders a large cash prize from school, and begins to see

prostitutes, as distance grows between him and his drunken father.

Stephen Dedalus has an aesthetic epiphany along Dollymount Strand.

As Stephen abandons himself to sensual pleasures, his class is taken on a religious retreat, where the boys sit through sermons. Stephen pays special attention to those on pride, guilt, punishment and the Four Last Things

(death, judgement, Hell, and Heaven). He feels that the words of the

sermon, describing horrific eternal punishment in hell, are directed at

himself and, overwhelmed, comes to desire forgiveness. Overjoyed at his

return to the Church, he devotes himself to acts of ascetic repentance,

though they soon devolve to mere acts of routine, as his thoughts turn

elsewhere. His devotion comes to the attention of the Jesuits, and they

encourage him to consider entering the priesthood.

Stephen takes time to consider, but has a crisis of faith because of

the conflict between his spiritual beliefs and his aesthetic ambitions.

Along Dollymount Strand

he spots a girl wading, and has an epiphany in which he is overcome

with the desire to find a way to express her beauty in his writing.

As a student at University College, Dublin, Stephen grows

increasingly wary of the institutions around him: Church, school,

politics and family. In the midst of the disintegration of his family's

fortunes his father berates him and his mother urges him to return to

the Church.

An increasingly dry, humourless Stephen explains his alienation from

the Church and the aesthetic theory he has developed to his friends, who

find that they cannot accept either of them.

Stephen concludes that Ireland is too restricted to allow him to

express himself fully as an artist, so he decides that he will have to

leave. He sets his mind on self-imposed exile, but not without declaring

in his diary his ties to his homeland:

... I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

Style

The novel is a bildungsroman novel and captures the essence of character growth and understanding of the world around them. The novel mixes third-person narrative with free indirect speech, which allows both identification with and distance from Stephen. The narrator refrains from judgement. The omniscient narrator of the earlier Stephen Hero informs the reader as Stephen sets out to write "some pages of sorry verse," while Portrait gives only Stephen's attempts, leaving the evaluation to the reader.

The novel is written primarily as a third-person narrative

with minimal dialogue until the final chapter. This chapter includes

dialogue-intensive scenes alternately involving Stephen, Davin and

Cranly. An example of such a scene is the one in which Stephen posits

his complex Thomist

aesthetic theory in an extended dialogue. Joyce employs first-person

narration for Stephen's diary entries in the concluding pages of the

novel, perhaps to suggest that Stephen has finally found his own voice

and no longer needs to absorb the stories of others.

Joyce fully employs the free indirect style to demonstrate Stephen's

intellectual development from his childhood, through his education, to

his increasing independence and ultimate exile from Ireland as a young

man. The style of the work progresses through each of its five chapters,

as the complexity of language and Stephen's ability to comprehend the

world around him both gradually increase.

The book's opening pages communicate Stephen's first stirrings of

consciousness when he is a child. Throughout the work language is used

to describe indirectly the state of mind of the protagonist and the

subjective effect of the events of his life.

The writing style is notable also for Joyce's omission of

quotation marks: he indicates dialogue by beginning a paragraph with a

dash, as is commonly used in French, Spanish or Russian publications.

Themes

Identity

As

a narrative which depicts a character throughout his formative years,

M. Angeles Conde-Parrilla posits that identity is possibly the most

prevalent theme in the novel.

Towards the beginning of the novel, Joyce depicts the young Stephen's

growing consciousness, which is said to be a condensed version of the

arc of Dedalus' entire life, as he continues to grow and form his

identity.

Stephen's growth as an individual character is important because

through him Joyce laments Irish society's tendency to force individuals

to conform to types, which some say marks Stephen as a modernist

character. Themes that run through Joyce's later novels find expression there.

Religion

As

Stephen transitions into adulthood, he leaves behind his Catholic

religious identity, which is closely tied to the national identity of

Ireland. His rejection of this dual identity is also a rejection of constraint and an embrace of freedom in identity. Furthermore, the references to Dr Faustus

throughout the novel conjure up something demonic in Stephen renouncing

his Catholic faith. When Stephen stoutly refuses to serve his Easter

duty later in the novel, his tone mirrors characters like Faust and

Lucifer in its rebelliousness.

Myth of Daedalus

The myth of Daedalus and Icarus

has parallels in the structure of the novel, and gives Stephen his

surname, as well as the epigraph containing a quote from Ovid's Metamorphoses.

According to Ivan Canadas, the epigraph may parallel the heights and

depths that end and begin each chapter, and can be seen to proclaim the

interpretive freedom of the text.

Stephen's surname being connected to Daedalus may also call to mind the

theme of going against the status quo, as Daedalus defies the King of

Crete.

Irish freedom

Stephen's

struggle to find identity in the novel parallels the Irish struggle for

independence during the early twentieth century. He rejects any

outright nationalism, and is often prejudiced toward those that use

Hiberno-English, which was the marked speech patterns of the Irish rural

and lower-class.

However, he is also heavily concerned with his country's future and

understands himself as an Irishman, which then leads him to question how

much of his identity is tied up in said nationalism.

Critical reception

While some critics take the prose to be too ornate, critics on the

whole praise the novel and its complexity, heralding Joyce's talent and

the beauty of the novel's originality. These critics view potentially

apparent lack of focus as intentional formlessness which imitates moral

chaos in the developing mind. The lens of vulgarity is also commented

on, as the novel is unafraid to delve the disgusting topics of

adolescence. In many instances, critics that comment on the novel as a

work of genius may concede that the work does not always exhibit this

genius throughout.

A Portrait won Joyce a reputation for his literary skills, as well as a patron, Harriet Shaw Weaver, the business manager of The Egoist.

In 1917 H. G. Wells wrote that "one believes in Stephen Dedalus as one believes in few characters in fiction," while warning readers of Joyce's "cloacal obsession," his insistence on the portrayal of bodily functions that Victorian morality had banished from print.

Adaptations

A film version adapted for the screen by Judith Rascoe and directed by Joseph Strick was released in 1977. It features Bosco Hogan as Stephen Dedalus and T. P. McKenna as Simon Dedalus. John Gielgud plays Father Arnall, the priest whose lengthy sermon on Hell terrifies the teenage Stephen.

The first stage version was produced by Léonie Scott-Matthews at Pentameters Theatre in 2012 using an adaptation by Tom Neill.

Hugh Leonard's stage work Stephen D is an adaptation of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Stephen Hero. It was first produced at the Gate Theatre during the Dublin Theatre Festival of 1962.

As of 2017 computer scientists and literature scholars at University College Dublin, Ireland

are in a collaboration to create the multimedia version of this work,

by charting the social networks of characters in the novel. Animations

in the multimedia editions express the relation of every character in

the chapter to the others.