Aerodynamic returning boomerang

| |

| First played | Ancient |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Mixed gender | No |

| Type | Throwing sport |

| Equipment | Boomerang |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Australia |

| Olympic | No |

| World Games | 1989 (invitational) |

A boomerang is a thrown tool, typically constructed as a flat airfoil, that is designed to spin about an axis perpendicular to the direction of its flight. A returning boomerang is designed to return to the thrower. It is well-known as a weapon used by Indigenous Australians for hunting.

Boomerangs have been historically used for hunting, as well as sport and entertainment. They are commonly thought of as an Australian icon, and come in various shapes and sizes.

Description

A boomerang is a throwing stick with certain aerodynamic

properties, traditionally made of wood, but boomerang-like devices have

also been made from bones. Modern boomerangs used for sport may be made

from plywood or plastics such as ABS, polypropylene, phenolic paper, or carbon fibre-reinforced plastics.

Boomerangs come in many shapes and sizes depending on their geographic

or tribal origins and intended function. Many people think of a

boomerang as the Australian type, although today there are many types of

more easily usable boomerangs, such as the cross-stick, the pinwheel,

the tumble-stick, the Boomabird, and many other less common types.

An important distinction should be made between returning

boomerangs and non-returning boomerangs. Returning boomerangs fly and

are examples of the earliest heavier-than-air human-made flight. A

returning boomerang has two or more airfoil wings arranged so that the spinning creates unbalanced aerodynamic forces that curve its path so that it travels in an ellipse, returning to its point of origin when thrown correctly. While a throwing stick

can also be shaped overall like a returning boomerang, it is designed

to travel as straight as possible so that it can be aimed and thrown

with great force to bring down the game. Its surfaces are therefore

symmetrical and not with the aerofoils that give the returning boomerang

its characteristic curved flight.

The most recognisable type of the boomerang is the L-shaped

returning boomerang; while non-returning boomerangs, throwing sticks (or

kylies) were used as weapons, returning boomerangs have been used

primarily for leisure or recreation. Returning boomerangs were also used

to decoy birds of prey, thrown above the long grass to frighten game birds into flight and into waiting nets. Modern returning boomerangs can be of various shapes or sizes.

Just like the hunting boomerang

of the aboriginal Australians, the valari also did not return to the

thrower but flew straight. Boomerangs used in competitions have

specially designed air-foiling mechanism to enable return, but the

hunting Boomerangs are meant to float straight and hit the target.

Valaris are made in many shapes and sizes. The history of the valari is

rooted in ancient times and evidences can be found in Tamil Sangam

literature "Purananuru". The usual form consists of two limbs set at an

angle; one is thin and tapering while the other is rounded and is used

as a handle. Valaris are usually made of iron which is melted and poured

into moulds, although some may have wooden limbs tipped with iron.

Alternatively, the limbs may have lethally sharpened edges; special

daggers are known as kattari, double-edged and razor sharp, may be attached to some valari.

Etymology

The

origin of the term is mostly certain, but many researchers have

different theories on how the word entered into the English vocabulary.

One source asserts that the term entered the language in 1827, adapted

from an extinct Aboriginal language of New South Wales, Australia, but mentions a variant, wo-mur-rang, which it dates to 1798. The boomerang was first encountered by western people at Farm Cove (Port Jackson), Australia, in December 1804, when a weapon was witnessed during a tribal skirmish:

... the white spectators were justly astonished at the dexterity and incredible force with which a bent, edged waddy resembling slightly a Turkish scimytar, was thrown by Bungary, a native distinguished by his remarkable courtesy. The weapon, thrown at 20 or 30 yards [18 or 27 m] distance, twirled round in the air with astonishing velocity, and alighting on the right arm of one of his opponents, actually rebounded to a distance not less than 70 or 80 yards [64 or 73 m], leaving a horrible contusion behind, and exciting universal admiration.

— The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 23 December 1804

David Collins listed "Wo-mur-rāng" as one of eight aboriginal "Names of clubs" in 1798. but was probably referring to the Woomera, which is actually a spear thrower. A 1790 anonymous manuscript on aboriginal language of New South Wales reported "Boo-mer-rit" as "the Scimiter".

In 1822, it was described in detail and recorded as a "bou-mar-rang" in the language of the Turuwal people (a sub-group of the Darug) of the Georges River near Port Jackson. The Turawal used other words for their hunting sticks but used "boomerang" to refer to a returning throw-stick.

History

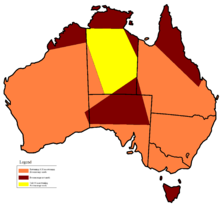

Distribution of boomerangs in Australia

Australian Aboriginal boomerangs

Boomerangs were, historically, used as hunting weapons, percussive musical instruments, battle clubs, fire-starters, decoys for hunting waterfowl,

and as recreational play toys. The smallest boomerang may be less than

10 centimetres (4 in) from tip to tip, and the largest over 180 cm

(5.9 ft) in length. Tribal

boomerangs may be inscribed or painted with designs meaningful to their

makers. Most boomerangs seen today are of the tourist or competition

sort, and are almost invariably of the returning type.

Depictions of boomerangs being thrown at animals, such as kangaroos,

appear in some of the oldest rock art in the world, the Indigenous Australian rock art of the Kimberly region, which is potentially up to 50,000 years old. Stencils and paintings of boomerangs also appear in the rock art of West Papua, including on Bird's Head Peninsula and Kaimana, likely dating to the Last Glacial Maximum, when lower sea levels led to cultural continuity between Papua and Arnhem Land in Northern Australia. The oldest surviving Australian Aboriginal boomerangs come from a cache found in a peat bog in the Wyrie Swamp of South Australia and date to 10,000 BC.

Although traditionally thought of as Australian, boomerangs have

been found also in ancient Europe, Egypt, and North America. There is

evidence of the use of non-returning boomerangs by the Native Americans

of California and Arizona, and inhabitants of southern India for killing birds and rabbits. Some boomerangs were not thrown at all, but were used in hand to hand combat by Indigenous Australians. Ancient Egyptian examples, however, have been recovered, and experiments have shown that they functioned as returning boomerangs. Hunting sticks discovered in Europe seem to have formed part of the Stone Age arsenal of weapons. One boomerang that was discovered in Obłazowa Cave in the Carpathian Mountains in Poland was made of mammoth's tusk and is believed, based on AMS dating of objects found with it, to be about 30,000 years old. In the Netherlands, boomerangs have been found in Vlaardingen and Velsen from the first century BC. King Tutankhamun, the famous Pharaoh

of ancient Egypt, who died over 3,300 years ago, owned a collection of

boomerangs of both the straight flying (hunting) and returning variety.

4

boomerangs of the tomb of pharahoh Tutankhamun (−1336-1326 BC). These

hardwood boomerangs could not return to their launcher due to their

curvature unlike other boomerangs found in the tomb.

No one knows for sure how the returning boomerang was invented, but

some modern boomerang makers speculate that it developed from the

flattened throwing stick, still used by the Australian Aborigines and other indigenous peoples around the world, including the Navajo

in North America. A hunting boomerang is delicately balanced and much

harder to make than a returning one. The curving flight characteristic

of returning boomerangs was probably first noticed by early hunters

trying to "tune" their throwing sticks to fly straight.

It is thought by some that the shape and elliptical flight path

of the returning boomerang makes it useful for hunting birds and small

animals, or that noise generated by the movement of the boomerang

through the air, or, by a skilled thrower, lightly clipping leaves of a

tree whose branches house birds, would help scare the birds towards the

thrower. It is further supposed by some that this was used to frighten

flocks or groups of birds into nets that were usually strung up between

trees or thrown by hidden hunters.

In southeastern Australia, it is claimed that boomerangs were made to

hover over a flock of ducks; mistaking it for a hawk, the ducks would

dive away, toward hunters armed with nets or clubs.

Traditionally, most boomerangs used by aboriginal groups in

Australia were non-returning. These weapons, sometimes called

"throwsticks" or "kylies", were used for hunting a variety of prey, from

kangaroos

to parrots; at a range of about 100 metres (330 ft), a 2-kg (4.4 lb)

non-returning boomerang could inflict mortal injury to a large animal.

A throwstick thrown nearly horizontally may fly in a nearly straight

path and could fell a kangaroo on impact to the legs or knees, while the

long-necked emu could be killed by a blow to the neck.

Hooked non-returning boomerangs, known as "beaked kylies", used in

northern Central Australia, have been claimed to kill multiple birds

when thrown into a dense flock. Throwsticks are used as multi-purpose

tools by today's aboriginal peoples, and besides throwing could be

wielded as clubs, used for digging, used to start friction fires, and

are sonorous when two are struck together.

Modern usage

Sport boomerangs

Today, boomerangs are mostly used for recreation. There are different

types of throwing contests: accuracy of return; Aussie round; trick

catch; maximum time aloft;

fast catch; and endurance (see below). The modern sport boomerang

(often referred to as a 'boom' or 'rang') is made of Finnish birch plywood, hardwood, plastic or composite materials

and comes in many different shapes and colours. Most sport boomerangs

typically weigh less than 100 grams (3.5 oz), with MTA boomerangs

(boomerangs used for the maximum-time-aloft event) often under 25 grams

(0.9 oz).

Boomerangs have also been suggested as an alternative to clay pigeons in shotgun sports, where the flight of the boomerang better mimics the flight of a bird offering a more challenging target.

The modern boomerang is often computer-aided designed with precision airfoils. The number of "wings" is often more than 2 as more lift is provided by 3 or 4 wings than by 2.

In 1992, German astronaut Ulf Merbold performed an experiment aboard Spacelab that established that boomerangs function in zero gravity as they do on Earth. French Astronaut Jean-François Clervoy aboard Mir repeated this in 1997. In 2008, Japanese astronaut Takao Doi again repeated the experiment on board the International Space Station.

Boomerangs for sale at the 2005 Melbourne Show

Beginning in the later part of the twentieth century, there has been a

bloom in the independent creation of unusually designed art boomerangs.

These often have little or no resemblance to the traditional historical

ones and on first sight some of these objects may not look like

boomerangs at all. The use of modern thin plywoods and synthetic

plastics have greatly contributed to their success. Designs are very

diverse and can range from animal inspired forms, humorous themes,

complex calligraphic and symbolic shapes, to the purely abstract.

Painted surfaces are similarly richly diverse. Some boomerangs made

primarily as art objects do not have the required aerodynamic properties

to return.

Aerodynamics

A

returning boomerang is a rotating wing. It consists of two or more

arms, or wings, connected at an angle; each wing is shaped as an airfoil section. Although it is not a requirement that a boomerang be in its traditional shape, it is usually flat.

Boomerangs can be made for right or left handed throwers. The

difference between right and left is subtle, the planform is the same

but the leading edges of the aerofoil sections are reversed. A

right-handed boomerang makes a counter-clockwise, circular flight to the

left while a left-handed boomerang flies clockwise to the right.

Most sport boomerangs weigh between 70 to 110 grams (2.5 to 3.9 oz),

have a wingspan of 250 to 350 millimetres (9.8 to 13.8 in) and a range

of between 20 and 40 m (22 and 44 yd).

A falling boomerang starts spinning, and most then fall in a

spiral. When the boomerang is thrown with high spin, a boomerang flies

in a curved rather than a straight line. When thrown correctly, a

boomerang returns to its starting point.

As the wing rotates and the boomerang moves through the air, the airflow

over the wings creates lift on both "wings". However, during one-half

of each blade's rotation, it sees a higher airspeed, because the

rotation tip-speed and the forward speed add, and when it is in the

other half of the rotation, the tip speed subtracts from the forward

speed. Thus if thrown nearly upright each blade generates more lift at

the top than the bottom.

While it might be expected that this would cause the boomerang to tilt

around the axis of travel, because the boomerang has significant angular

momentum, the gyroscopic precession causes the plane of rotation to tilt about an axis that is 90 degrees to the direction of flight causing it to turn. When thrown in the horizontal plane, as with a Frisbee,

instead of in the vertical, the same gyroscopic precession will cause

the boomerang to fly violently, straight up into the air and then crash.

Fast Catch boomerangs usually have three or more symmetrical

wings (seen from above), whereas a Long Distance boomerang is most often

shaped similar to a question mark.

Maximum Time Aloft boomerangs mostly have one wing considerably longer

than the other. This feature, along with carefully executed bends and

twists in the wings help to set up an 'auto-rotation' effect to maximise

the boomerang's hover-time in descending from the highest point in its

flight.

Some boomerangs have turbulators—bumps

or pits on the top surface that act to increase the lift as boundary

layer transition activators (to keep attached turbulent flow instead of

laminar separation).

Throwing technique

Flight path of a returning boomerang

Boomerangs are generally thrown in treeless, large open spaces that

are twice as large as the range of the boomerang, the flight direction,

left or right will depend upon the boomerang, not the thrower. A

right-handed or left-handed boomerang can be thrown with either hand,

but throwing a boomerang with the wrong hand requires a throwing motion

that many throwers may find awkward. The following technique applies to a

right-handed boomerang, the directions are reversed for a left-handed

boomerang.

A properly thrown boomerang should curve around to the left,

climb gently, level out in mid-flight, arc around and descend slowly,

and then finish by popping up slightly, hovering, then stalling near the

thrower. Ideally, this momentary hovering or stalling will allow the

catcher the opportunity to clamp their hands shut horizontally on the

boomerang from above and below, sandwiching the centre between their

hands.

The boomerang is thrown held between finger and thumb at the

bottom end, in a near-vertical position, with the upper aerofoil section

to the outside of the thrower and the 'hook' of the boomerang facing

forward so as to present the leading edges of the aerofoils to the

slipstream when spinning.

The boomerang is aimed directly into, or 3 to 5 degrees right, of

the wind, and the flight then takes it left through the "eye of the

wind" and finally returning downwind. The accuracy of the throw starts

with an understanding of the weight and aerodynamics of that particular

boomerang and the strength and direction of the wind; from this, the

thrower chooses the precise angle of tilt of the boomerang from

vertical, the angle against the wind and the strength of the throw. The

stronger the wind, the softer the boomerang is thrown and the less the

tilt off vertical. The boomerang can be made to return without the aid

of any wind but the wind speed and direction must be taken into account.

A light wind of three to five miles per hour is considered ideal. If

the wind is strong enough to fly a kite, then it may be too strong for a

given boomerang.

A great deal of trial and error is required to perfect the throw

over time. Different boomerang designs have different flight

characteristics and are suitable for different conditions.

Competitions and records

A

World Record achievement was made on 3/6/07 by Tim Lendrum in Aussie

Round. Tim scored 96 out of 100, giving him a National Record as well as

an equal World Record throwing an "AYR" made by expert boomerang maker

Adam Carroll from ONE Boomerangs formerly Real Boomerangs.

In international competition, a world cup is held every second year. As of 2017,

teams from Germany and the United States dominated international

competition. The individual World Champion title was won in 2000, 2002,

2004, 2012 and 2016 by Swiss thrower Manuel Schütz. In 1992, 1998, 2006

and 2008 Fridolin Frost from Germany won the title.

The team competitions of 2012 and 2014 were won by Boomergang (an

international team). World champions were Germany in 2012 and Japan in

2014 for the first time. Boomergang was formed by individuals from

several countries, including the Colombian Alejandro Palacio. In 2016

USA became team world champion.

Competition disciplines

Modern boomerang tournaments usually involve some or all of the events listed below

In all disciplines the boomerang must travel at least 20 metres (66 ft)

from the thrower. Throwing takes place individually. The thrower stands

at the centre of concentric rings marked on an open field.

Events include:

- Aussie Round: considered by many to be the ultimate test of boomeranging skills. The boomerang should ideally cross the 50-metre (160 ft) circle and come right back to the centre. Each thrower has five attempts. Points are awarded for distance, accuracy and the catch.

- Accuracy: points are awarded according to how close the boomerang lands to the centre of the rings. The thrower must not touch the boomerang after it has been thrown. Each thrower has five attempts. In major competitions there are two accuracy disciplines: Accuracy 100 and Accuracy 50.

- Endurance: points are awarded for the number of catches achieved in 5 minutes.

- Fast Catch: the time taken to throw and catch the boomerang five times. The winner has the fastest timed catches.

- Trick Catch/Doubling: points are awarded for trick catches behind the back, between the feet, and so on. In Doubling, the thrower has to throw two boomerangs at the same time and catch them in sequence in a special way.

- Consecutive Catch: points are awarded for the number of catches achieved before the boomerang is dropped. The event is not timed.

- MTA 100 (Maximal Time Aloft, 100 metres (328 ft)): points are awarded for the length of time spent by the boomerang in the air. The field is normally a circle measuring 100 m. An alternative to this discipline, without the 100 m restriction is called MTA unlimited.

- Long Distance: the boomerang is thrown from the middle point of a 40-metre (130 ft) baseline. The furthest distance travelled by the boomerang away from the baseline is measured. On returning, the boomerang must cross the baseline again but does not have to be caught. A special section is dedicated to LD below.

- Juggling: as with Consecutive Catch, only with two boomerangs. At any given time one boomerang must be in the air.

World records

- As of September 2017

| Discipline | Result | Name | Year | Tournament |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy 100 | 99 points | 2007 | ||

| Aussie Round | 99 points | 2007 | ||

| Endurance | 81 catches | 2005 | ||

| Fast Catch | 14.07 s | 2017 | ||

| Trick Catch/Doubling | 533 points | 2009 | ||

| Consecutive Catch | 2251 catches | 2009 | ||

| MTA 100 | 139.10 s | 2010 | ||

| MTA unlimited | 380.59 s | 2010 | ||

| Long Distance | 238 m | 1999 |

Guinness World Record – Smallest Returning Boomerang

Non-discipline record:

Smallest Returning Boomerang: Sadir Kattan of Australia in 1997 with 48

millimetres (1.9 in) long and 46 millimetres (1.8 in) wide. This tiny

boomerang flew the required 20 metres (22 yd), before returning to the

accuracy circles on 22 March 1997 at the Australian National

Championships.

Guinness World Record – Longest Throw of Any Object by a Human

A boomerang was used to set a Guinness World Record with a throw of 427.2 metres (1,402 ft) by David Schummy on 15 March 2005 at Murrarie Recreation Ground, Australia. This broke the record set by Erin Hemmings who threw an Aerobie 406.3 metres (1,333 ft) on 14 July 2003 at Fort Funston, San Francisco.

Long-distance versions

Long-distance boomerang throwers aim to have the boomerang go the

furthest possible distance while returning close to the throwing point.

In competition the boomerang must intersect an imaginary surface defined

as an infinite vertical

projection of a 40-metre (44 yd) line centred on the thrower. Outside

of competitions, the definition is not so strict, and throwers may be

happy simply not to walk too far to recover the boomerang.

General properties

Long-distance

boomerangs are optimised to have minimal drag while still having enough

lift to fly and return. For this reason, they have a very narrow

throwing window, which discourages many beginners from continuing with

this discipline. For the same reason, the quality of manufactured

long-distance boomerangs is often non-deterministic.

Today's long-distance boomerangs have almost all an S or ? – question mark shape and have a beveled

edge on both sides (the bevel on the bottom side is sometimes called an

undercut). This is to minimise drag and lower the lift. Lift must be

low because the boomerang is thrown with an almost total layover (flat).

Long-distance boomerangs are most frequently made of composite

material, mainly fibre glass epoxy composites.

Flight path

The projection of the flight path of long-distance boomerang on the ground resembles a water drop.

For older types of long-distance boomerangs (all types of so-called big

hooks), the first and last third of the flight path are very low, while

the middle third is a fast climb followed by a fast descent. Nowadays,

boomerangs are made in a way that their whole flight path is almost

planar with a constant climb during the first half of the trajectory and

then a rather constant descent during the second half.

From theoretical point of view, distance boomerangs are

interesting also for the following reason: for achieving a different

behaviour during different flight phases, the ratio of the rotation

frequency to the forward velocity has a U-shaped function, i.e., its derivative crosses 0. Practically, it means that the boomerang being at the furthest point has a very low forward velocity. The kinetic energy of the forward component is then stored in the potential energy.

This is not true for other types of boomerangs, where the loss of

kinetic energy is non-reversible (the MTAs also store kinetic energy in

potential energy during the first half of the flight, but then the

potential energy is lost directly by the drag).

Related terms

In Noongar language, kylie is a flat curved piece of wood similar in appearance to a boomerang that is thrown when hunting for birds and animals.

"Kylie" is one of the Aboriginal words for the hunting stick used in warfare and for hunting animals.

Instead of following curved flight paths, kylies fly in straight lines

from the throwers. They are typically much larger than boomerangs, and

can travel very long distances; due to their size and hook shapes, they

can cripple or kill an animal or human opponent. The word is perhaps an

English corruption of a word meaning "boomerang" taken from one of the

Western Desert languages, for example, the Warlpiri word "karli".