https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synaptogenesis

Synaptogenesis is the formation of synapses between neurons in the nervous system. Although it occurs throughout a healthy person's lifespan, an explosion of synapse formation occurs during early brain development, known as exuberant synaptogenesis. Synaptogenesis is particularly important during an individual's critical period, during which there is a certain degree of synaptic pruning due to competition for neural growth factors by neurons and synapses. Processes that are not used, or inhibited during their critical period will fail to develop normally later on in life.

Synaptogenesis is the formation of synapses between neurons in the nervous system. Although it occurs throughout a healthy person's lifespan, an explosion of synapse formation occurs during early brain development, known as exuberant synaptogenesis. Synaptogenesis is particularly important during an individual's critical period, during which there is a certain degree of synaptic pruning due to competition for neural growth factors by neurons and synapses. Processes that are not used, or inhibited during their critical period will fail to develop normally later on in life.

Formation of the neuromuscular junction

Function

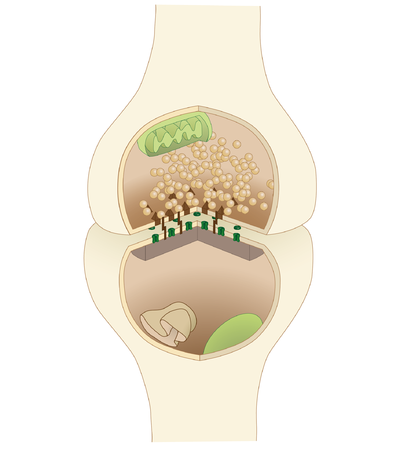

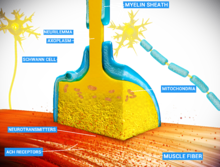

The neuromuscular junction

(NMJ) is the most well-characterized synapse in that it provides a

simple and accessible structure that allows for easy manipulation and

observation. The synapse itself is composed of three cells: the motor neuron, the myofiber, and the Schwann cell. In a normally functioning synapse, a signal will cause the motor neuron to depolarize, by releasing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh). Acetylcholine travels across the synaptic cleft where it reaches acetylcholine receptors (AChR) on the plasma membrane of the myofiber, the sarcolemma. As the AChRs open ion channels, the membrane depolarizes, causing muscle contraction. The entire synapse is covered in

a myelin sheath provided by the Schwann cell to insulate and encapsulate the junction.

Another important part of the neuromuscular system and central nervous system are the astrocytes.

While originally they were thought to have only functioned as support

for the neurons, they play an important role in functional plasticity of

synapses.

Origin and movement of cells

During

development, each of the three germ layer cell types arises from

different regions of the growing embryo. The individual myoblasts

originate in the mesoderm and fuse to form a multi-nucleated myotube.

During or shortly after myotube formation, motoneurons from the neural

tube form preliminary contacts with the myotube. The Schwann cells arise

from the neural crest and are led by the axons to their destination.

Upon reaching it, they form a loose, unmyelinated covering over the

innervating axons. The movement of the axons (and subsequently the

Schwann cells) is guided by the growth cone, a filamentous projection of

the axon that actively searches for neurotrophins released by the

myotube.

The specific patterning of synapse development at the

neuromuscular junction shows that the majority of muscles are innervated

at their midpoints. Although it may seem that the axons specifically

target the midpoint of the myotube, several factors reveal that this is

not a valid claim. It appears that after the initial axonal contact, the

newly formed myotube proceeds to grow symmetrically from that point of

innervation. Coupled with the fact that AChR density is the result of

axonal contact instead of the cause, the structural patterns of muscle

fibers can be attributed to both myotatic growth as well as axonal

innervation.

The preliminary contact formed between the motoneuron and the

myotube generates synaptic transmission almost immediately, but the

signal produced is very weak. There is evidence that Schwann cells may

facilitate these preliminary signals by increasing the amount of

spontaneous neurotransmitter release through small molecule signals.

After about a week, a fully functional synapse is formed following

several types of differentiation in both the post-synaptic muscle cell

and the pre-synaptic motoneuron. This pioneer axon is of crucial

importance because the new axons that follow have a high propensity for

forming contacts with well-established synapses.

Post-synaptic differentiation

The

most noticeable difference in the myotube following contact with the

motoneuron is the increased concentration of AChR in the plasma membrane

of the myotube in the synapse. This increased amount of AChR allows for

more effective transmission of synaptic signals, which in turn leads to

a more-developed synapse. The density of AChR is > 10,000/μm2 and approximately 10/μm2

around the edge. This high concentration of AChR in the synapse is

achieved through clustering of AChR, up-regulation of the AChR gene

transcription in the post-synaptic nuclei, and down-regulation of the

AChR gene in the non-synaptic nuclei.

The signals that initiate post-synaptic differentiation may be

neurotransmitters released directly from the axon to the myotube, or

they may arise from changes activated in the extracellular matrix of the

synaptic cleft.

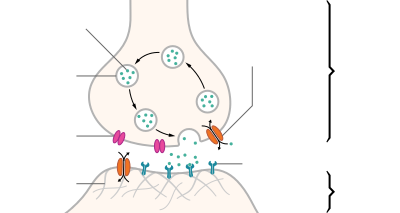

Clustering

AChR experiences multimerization within the post-synaptic membrane largely due to the signaling molecule Agrin.

The axon of the motoneuron releases agrin, a proteoglycan that

initiates a cascade that eventually leads to AChR association. Agrin

binds to a muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) receptor in the post-synaptic membrane, and this in turn leads to downstream activation of the cytoplasmic protein Rapsyn.

Rapsyn contains domains that allow for AChR association and

multimerization, and it is directly responsible for AChR clustering in

the post-synaptic membrane: rapsyn-deficient mutant mice fail to form

AChR clusters.

Synapse-specific transcription

The

increased concentration of AChR is not simply due to a rearrangement of

pre-existing synaptic components. The axon also provides signals that

regulate gene expression within the myonuclei directly beneath the

synapse. This signaling provides for localized up-regulation of

transcription of AChR genes and consequent increase in local AChR

concentration. The two signaling molecules released by the axon are

calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and neuregulin, which trigger a series of kinases that eventually lead to transcriptional activation of the AChR genes.

Extrasynaptic repression

Repression

of the AChR gene in the non-synaptic nuclei is an activity-dependent

process involving the electrical signal generated by the newly formed

synapse. Reduced concentration of AChR in the extrasynaptic membrane in

addition to increased concentration in the post-synaptic membrane helps

ensure the fidelity of signals sent by the axon by localizing AChR to

the synapse. Because the synapse begins receiving inputs almost

immediately after the motoneuron comes into contact with the myotube,

the axon quickly generates an action potential and releases ACh. The

depolarization caused by AChR induces muscle contraction and

simultaneously initiates repression of AChR gene transcription across

the entire muscle membrane. Note that this affects gene transcription at

a distance: the receptors that are embedded within the post-synaptic

membrane are not susceptible to repression.

Pre-synaptic differentiation

Although

the mechanisms regulating pre-synaptic differentiation are unknown, the

changes exhibited at the developing axon terminal are well

characterized. The pre-synaptic axon shows an increase in synaptic

volume and area, an increase of synaptic vesicles, clustering of

vesicles at the active zone, and polarization of the pre-synaptic

membrane. These changes are thought to be mediated by neurotrophin and

cell adhesion molecule release from muscle cells, thereby emphasizing

the importance of communication between the motoneuron and the myotube

during synaptogenesis. Like post-synaptic differentiation, pre-synaptic

differentiation is thought to be due to a combination of changes in gene

expression and a redistribution of pre-existing synaptic components.

Evidence for this can be seen in the up-regulation of genes expressing

vesicle proteins shortly after synapse formation as well as their

localization at the synaptic terminal.

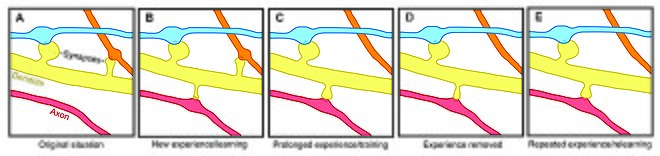

Synaptic maturation

Immature

synapses are multiply innervated at birth, due the high propensity for

new axons to innervate at a pre-existing synapse. As the synapse

matures, the synapses segregate and eventually all axonal inputs except

for one retract in a process called synapse elimination. Furthermore,

the post-synaptic end plate grows deeper and creates folds through

invagination to increase the surface area available for neurotransmitter

reception. At birth, Schwann cells form loose, unmyelinated covers over

groups of synapses, but as the synapse matures, Schwann cells become

dedicated to a single synapse and form a myelinated cap over the entire

neuromuscular junction.

Synapse elimination

The

process of synaptic pruning known as synapse elimination is a

presumably activity-dependent process that involves competition between

axons. Hypothetically, a synapse strong enough to produce an action

potential will trigger the myonuclei directly across from the axon to

release synaptotrophins that will strengthen and maintain

well-established synapses. This synaptic strengthening is not conferred

upon the weaker synapses, thereby starving them out. It has also been

suggested that in addition to the synaptotrophins released to the

synapse exhibiting strong activity, the depolarization of the

post-synaptic membrane causes release of synaptotoxins that ward off

weaker axons.

Synapse formation specificity

A

remarkable aspect of synaptogenesis is the fact that motoneurons are

able to distinguish between fast and slow-twitch muscle fibers;

fast-twitch muscle fibers are innervated by "fast" motoneurons, and

slow-twitch muscle fibers are innervated by "slow" motoneurons. There

are two hypothesized paths by which the axons of motoneurons achieve

this specificity, one in which the axons actively recognize the muscles

that they innervate and make selective decisions based on inputs, and

another that calls for more indeterminate innervation of muscle fibers.

In the selective paths, the axons recognize the fiber type, either by

factors or signals released specifically by the fast or slow-twitch

muscle fibers. In addition, selectivity can be traced to the lateral

position that the axons are predeterminately arranged in order to link

them to the muscle fiber that they will eventually innervate. The

hypothesized non-selective pathways indicate that the axons are guided

to their destinations by the matrix through which they travel.

Essentially, a path is laid out for the axon and the axon itself is not

involved in the decision-making process. Finally, the axons may

non-specifically innervate muscle fibers and cause the muscles to

acquire the characteristics of the axon that innervates them. In this

path, a "fast" motoneuron can convert any muscle fiber into a

fast-twitch muscle fiber. There is evidence for both selective and

non-selective paths in synapse formation specificity, leading to the

conclusion that the process is a combination of several factors.

Central nervous system synapse formation

Although

the study of synaptogenesis within the central nervous system (CNS) is

much more recent than that of the NMJ, there is promise of relating the

information learned at the NMJ to synapses within the CNS. Many similar

structures and basic functions exist between the two types of neuronal

connections. At the most basic level, the CNS synapse and the NMJ both

have a nerve terminal that is separated from the postsynaptic membrane

by a cleft containing specialized extracellular material. Both

structures exhibit localized vesicles at the active sites, clustered

receptors at the post-synaptic membrane, and glial cells that

encapsulate the entire synaptic cleft. In terms of synaptogenesis, both

synapses exhibit differentiation of the pre- and post-synaptic membranes

following initial contact between the two cells. This includes the

clustering of receptors, localized up-regulation of protein synthesis at

the active sites, and neuronal pruning through synapse elimination.

Despite these similarities in structure, there is a fundamental

difference between the two connections. The CNS synapse is strictly

neuronal and does not involve muscle fibers: for this reason the CNS

uses different neurotransmitter molecules and receptors. More

importantly, neurons within the CNS often receive multiple inputs that

must be processed and integrated for successful transfer of information.

Muscle fibers are innervated by a single input and operate in an all or

none fashion. Coupled with the plasticity that is characteristic of the

CNS neuronal connections, it is easy to see how increasingly complex

CNS circuits can become.

Factors regulating synaptogenesis in the CNS

Signaling

The

main method of synaptic signaling in the NMJ is through use of the

neurotransmitter acetylcholine and its receptor. The CNS homolog is

glutamate and its receptors, and one of special significance is the

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. It has been shown that activation

of NMDA receptors initiates synaptogenesis through activation of

downstream products. The heightened level of NMDA receptor activity

during development allows for increased influx of calcium, which acts as

a secondary signal. Eventually, immediate early genes (IEG) are activated by transcription factors and the proteins required for neuronal differentiation are translated.

The NMDA receptor function is associated with the estrogen receptor in

hippocampal neurons. Experiments conducted with estradiol show that

exposure to the estrogen significantly increases synaptic density and

protein concentration.

Synaptic signaling during synaptogenesis is not only

activity-dependent, but is also dependent on the environment in which

the neurons are located. For instance, brain-derived neurotrophic factor

(BDNF) is produced by the brain and regulates several functions within

the developing synapse, including enhancement of transmitter release,

increased concentration of vesicles, and cholesterol biosynthesis.

Cholesterol is essential to synaptogenesis because the lipid rafts that

it forms provide a scaffold upon which numerous signaling interactions

can occur. BDNF-null mutants show significant defects in neuronal growth

and synapse formation.

Aside from neurotrophins, cell-adhesion molecules are also essential to

synaptogenesis. Often the binding of pre-synaptic cell-adhesion

molecules with their post-synaptic partners triggers specializations

that facilitate synaptogenesis. Indeed, a defect in genes encoding neuroligin, a cell-adhesion molecule found in the post-synaptic membrane, has been linked to cases of autism and mental retardation. Finally, many of these signaling processes can be regulated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) as the targets of many MMPs are these specific cell-adhesion molecules.

Morphology

The special structure found in the CNS that allows for multiple inputs is the dendritic spine,

the highly dynamic site of excitatory synapses. This morphological

dynamism is due to the specific regulation of the actin cytoskeleton,

which in turn allows for regulation of synapse formation.

Dendritic spines exhibit three main morphologies: filopodia, thin

spines, and mushroom spines. The filopodia play a role in synaptogenesis

through initiation of contact with axons of other neurons. Filopodia of

new neurons tend to associate with multiply synapsed axons, while the

filopodia of mature neurons tend to sites devoid of other partners. The

dynamism of spines allows for the conversion of filopodia into the

mushroom spines that are the primary sites of glutamate receptors and

synaptic transmission.

Environmental enrichment

Rats raised with environmental enrichment have 25% more synapses than controls. This effect occurs whether a more stimulating environment is experienced immediately following birth, after weaning, or during maturity. Stimulation effects not only synaptogenesis upon pyramidal neurons but also stellate ones.

Contributions of the Wnt protein family

The (Wnt) family, includes several embryonic morphogens

that contribute to early pattern formation in the developing embryo.

Recently data have emerged showing that the Wnt protein family has roles

in the later development of synapse formation and plasticity. Wnt contribution to synaptogenesis has been verified in both the central nervous system and the neuromuscular junction.

Central nervous system

Wnt family members contribute to synapse formation in the cerebellum by inducing presynaptic and postsynaptic terminal formation. This brain region contains three main neuronal cell types- Purkinje cells, granule cells and mossy fiber cells. Wnt-3 expression contributes to Purkinje cell neurite outgrowth and synapse formation. Granule cells express Wnt-7a to promote axon spreading and branching in their synaptic partner, mossy fiber cells. Retrograde secretion of Wnt-7a to mossy fiber cells causes growth cone enlargement by spreading microtubules. Furthermore, Wnt-7a retrograde signaling recruits synaptic vesicles and presynaptic proteins to the synaptic active zone.

Wnt-5a performs a similar function on postsynaptic granule cells; this

Wnt stimulates receptor assembly and clustering of the scaffolding

protein PSD-95.

In the hippocampus Wnts in conjunction with cell electrical activity promote synapse formation. Wnt7b is expressed in maturing dendrites, and the expression of the Wnt receptor Frizzled (Fz), increases highly with synapse formation in the hippocampus. NMDA glutamate receptor activation increases Wnt2 expression. Long term potentiation (LTP) due to NMDA activation and subsequent Wnt expression leads to Fz-5 localization at the postsynaptic active zone. Furthermore, Wnt7a and Wnt2 signaling after NMDA receptor mediated LTP leads to increased dendritic arborization and regulates activity induced synaptic plasticity.

Blocking Wnt expression in the hippocampus mitigates these activity

dependent effects by reducing dendritic arborization and subsequently,

synaptic complexity.

Neuromuscular junction

Similar

mechanisms of action by Wnts in the central nervous system are observed

in the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) as well. In the Drosophila NMJ mutations in the Wnt5 receptor Derailed (drl) reduce the number of and density of synaptic active zones. The major neurotransmitter in this system is glutamate. Wnt is needed to localize glutamatergic receptors on postsynaptic muscle cells. As a result, Wnt mutations diminish evoked currents on the postsynaptic muscle.

In the vertebrate NMJ, motor neuron expression of Wnt-11r contributes to acetylcholine receptor

(AChR) clustering in the postsynaptic density of muscle cells. Wnt-3 is

expressed by muscle fibers and is secreted retrogradely onto motor

neurons. In motor neurons, Wnt-3 works with Agrin to promote growth cone enlargement, axon branching and synaptic vesicle clustering.